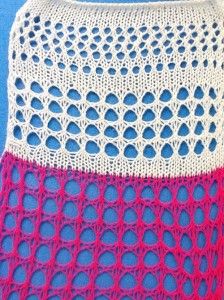

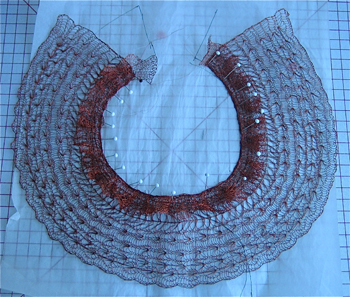

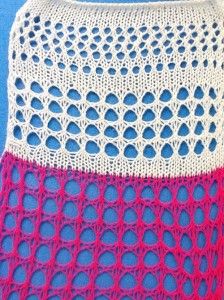

The goal is to produce a large-scale mesh without hand techniques or extra steps.

In both slip and tuck, every punched hole, black square in mylar, or pixel in electronic downloads that bring a needle out to D position (for some unfathomable reason Brother needle positions go A, B, D, E, poor C got skipped) will result in a knit stitch. In the slip setting the non selected needles get skipped creating floats, while in the tuck setting, the non selected needles will hold a loop in the needle hook until that needle is returned to the D position. Side-by-side loops are troublesome in any stitch type. That said, tuck can be employed to sequentially lay down loops in some patterns where the lace carriage moves to produce side by side empty needles as part of the planned design.

The usual caution with such fabrics: extension rails must be used since both carriages engage the belt. The yarn needs to be “friendly” enough to not break easily. Since stitches travel across a wider gap than in single eyelet lace, the tension needs to be looser as well. Small changes can make a big difference, and so can patience. If end stitches are selected prior to the lace carriage making the next row of transfers, push them back to B manually so as not to produce decreases or dropped stitches.

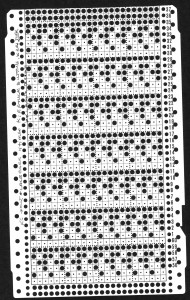

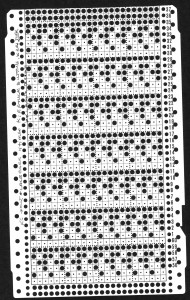

Working the punchcard on a punchcard machine:

The lace carriage is set for normal lace, preselects the first row of knitting with the punchcard not locked on its first pass to the right. The KH carriage is set on KC I with both tuck buttons depressed. Each carriage works in sequences of 4 passes throughout.

Actions performed by the carriages as they make their next pass to the opposite side:

Lace carriage

COL: moves to the right with no preselection

COR: no transfers, preselects for transfers to the right

COL: transfers to the right, preselects transfers to the left

COR: transfers to the left, preselects for the first tuck row. There will be 3 single needles with 3 stitches on each of them and two empty needles on each side

Knit carriage:

COR: knits first tuck row, makes the same preselection

COL: knits second tuck row, preselect the next tuck row, on a different needle position

COR: knits third tuck row, in the alternate location, preselects for all knit row

COL: knits all stitches, preselects blank row

Some observations: the top bind off as seen in the swatch below, was tight for the fabric. To maximize its width, the bind-off should be around at least 2 gate pegs, even 3 if needed. This allows for completing the task on the machine without adding more work and adding hand techniques. Tuck stitch produces a knit that tends to be short and wide, lace wants to open up with blocking as well, so this fabric definitely will want to spread. The top approximate 1/3 of the swatch below was kit using the same white yarn but in standard single needle mesh, making the size difference in “holes” created with the tuck method easy to see. The white is a 2/8 wool, the other a 16/2 mystery fiber I usually use as waste yarn.

For me this experiment will probably fall in the “now that I’ve done it, broken several rules, and have a good result I am over it” category.

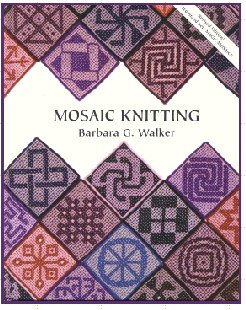

Mosaic knitting companion CD by Morgan Hicks 381 motifs “charted and converted for your electronic knitting machine or crochet, .pat or .pcx format”.

Mosaic knitting companion CD by Morgan Hicks 381 motifs “charted and converted for your electronic knitting machine or crochet, .pat or .pcx format”.