I began a series of posts on miters and spirals created on the knitting machine back in 2011. The oldest posts, knitting math and pies, back to that pie, a bit of holding, and revisiting miters and spirals to form varied shapes begin to address creating flat circles in machine knitting using holding techniques.

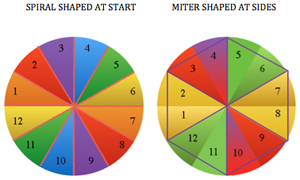

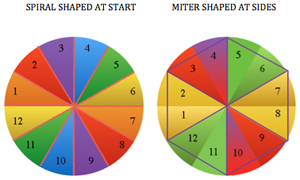

Hand-knitting in circular format and crochet share some similarities. There are 2 methods of constructing circular work in crochet. 1: in rounds, (akin to knit miters in shape) where the end of each circular row is joined up to its own beginning to form a ring. A new starting chain (s) is formed to take the row to the proper height for the next row to remain constant. Depending on the pattern, one has the option of continuing by turning the work or not at the end of each row. Doing so allows the opportunity of altering textures and work on the fronts or backs of stitches. 2: in spirals. Rather than joining the ring, one continues on by going to the tops of the posts in the previous row.

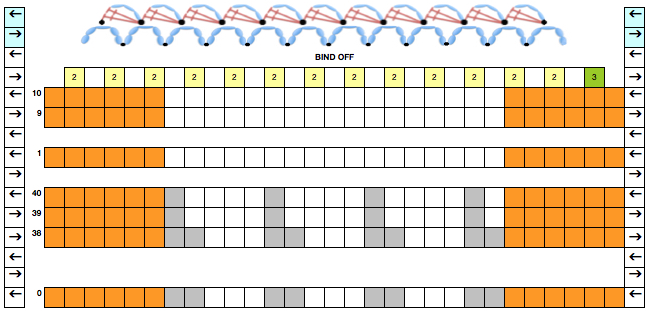

With spirals, it is useful to mark the beginning of each round. Knitting markers shaped like safety pins are handy for that purpose. A line in a contrasting color can also be created using a separate strand of yarn and alternating carrying it back or to the front prior to forming the first stitch in the new row.

As with knitting, crocheted circles are not true circles, but rather, they are polygons. The way to make shapes more circular is to scramble the location of the increase points, putting them in different starting positions in each round (always spacing them equally and keeping the formula). Within limits, one may make the starting number of stitches in the first round a multiple of the number of segments in the finished shape.

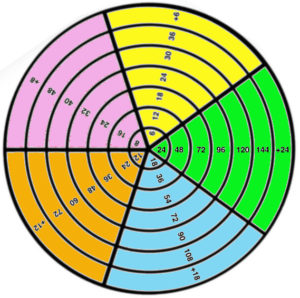

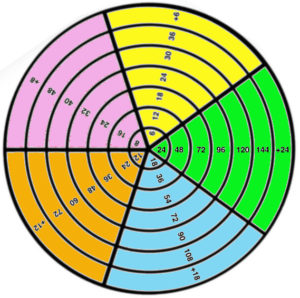

With the creation of a flat circle in mind, the number of stitches needed depends on the height of the stitch. The taller the stitch, the greater the number of stitches required. If the stitch stays the same throughout, the number of stitches added on each round is constant. Test work regularly at intervals as the work grows by placing it on a firm, flat surface, to see if working only one stitch into each stitch is required / enough at that point to maintain the shape. The more segments, the smoother the circumference.

Unlike in hand-knitting, the first loop on the hook does not count as a stitch until you make it into something.

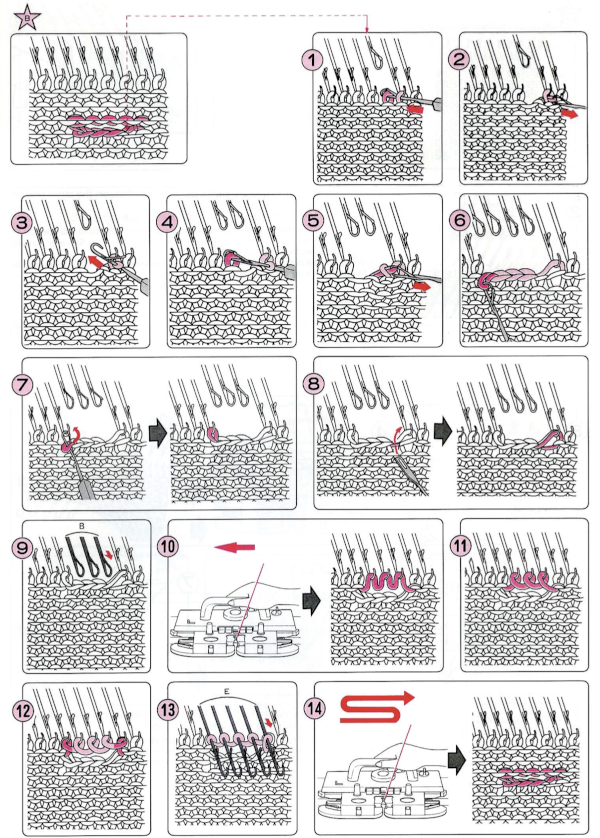

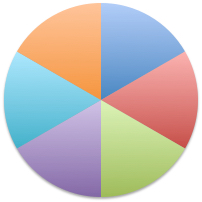

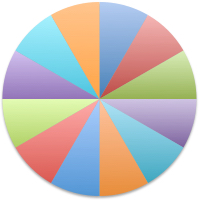

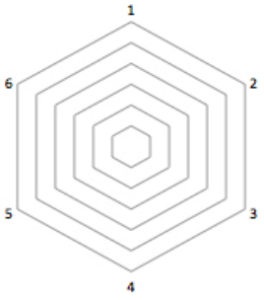

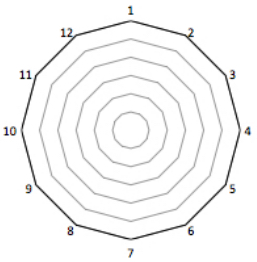

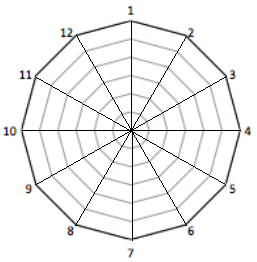

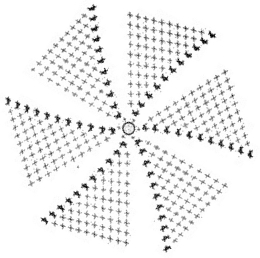

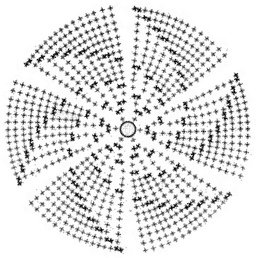

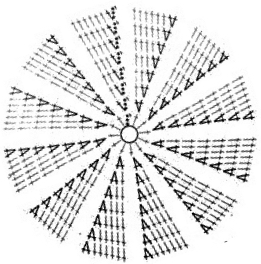

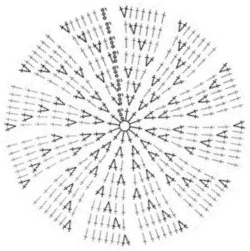

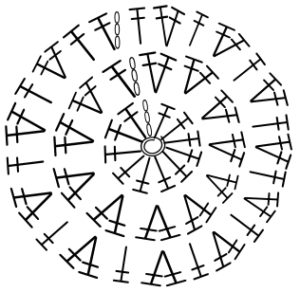

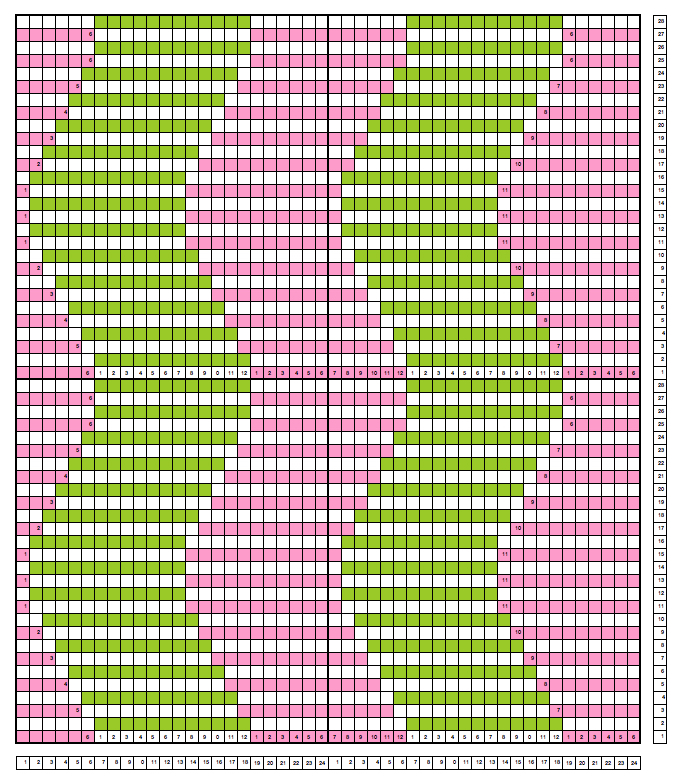

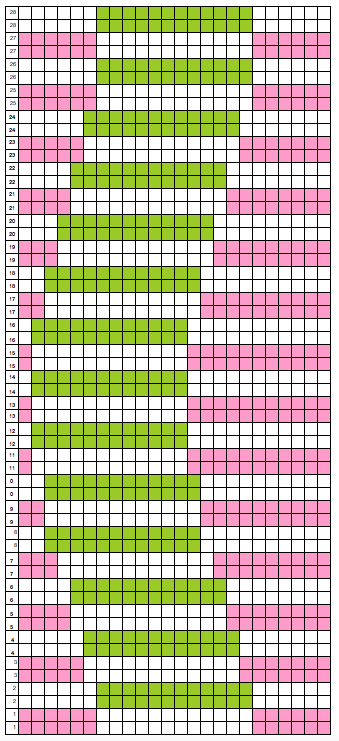

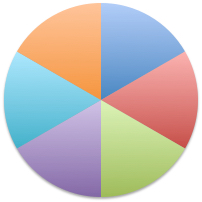

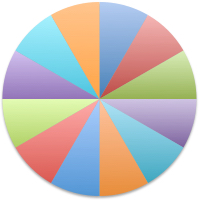

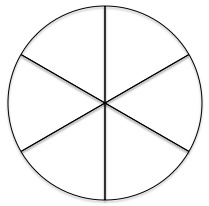

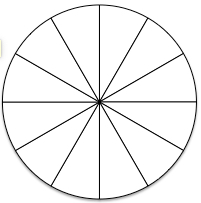

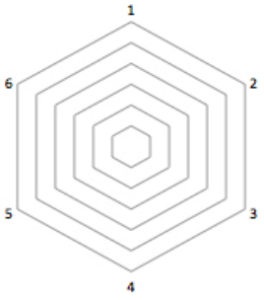

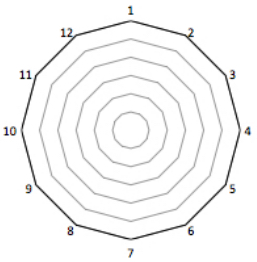

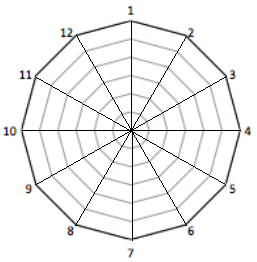

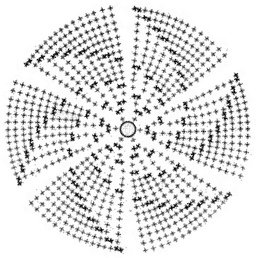

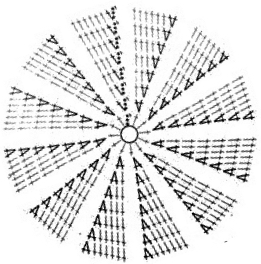

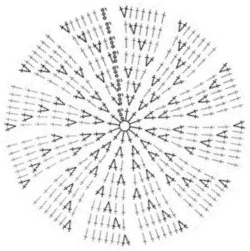

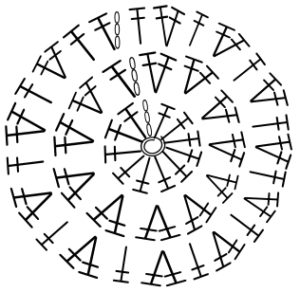

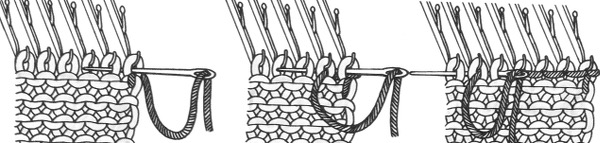

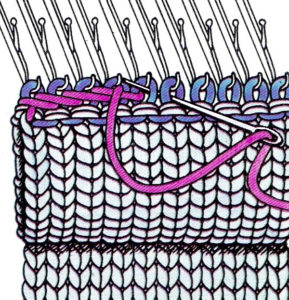

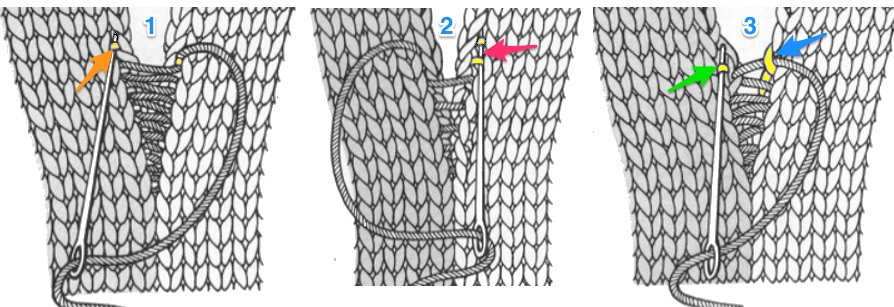

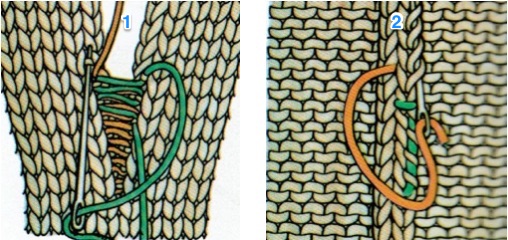

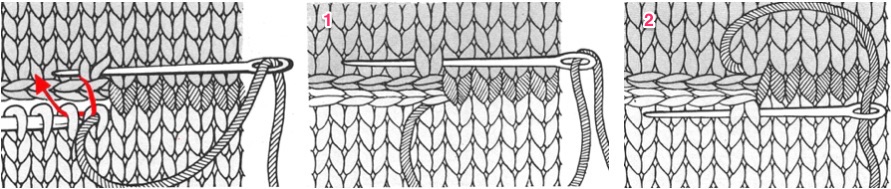

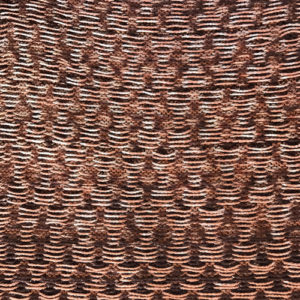

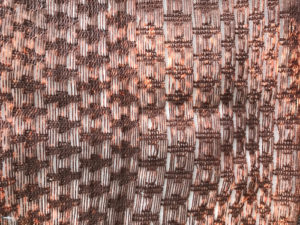

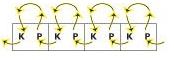

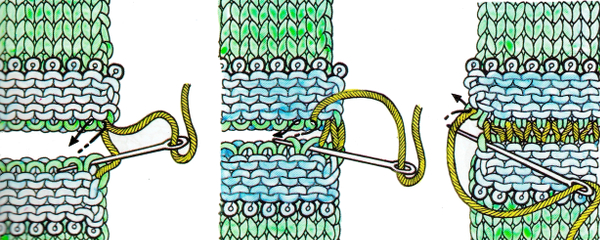

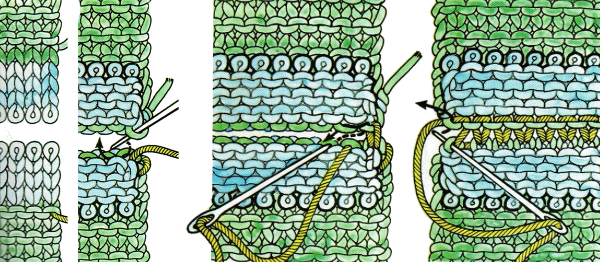

Spirals or miters knit on the machine begin with their radius; one possible construction method may be inferred from these images

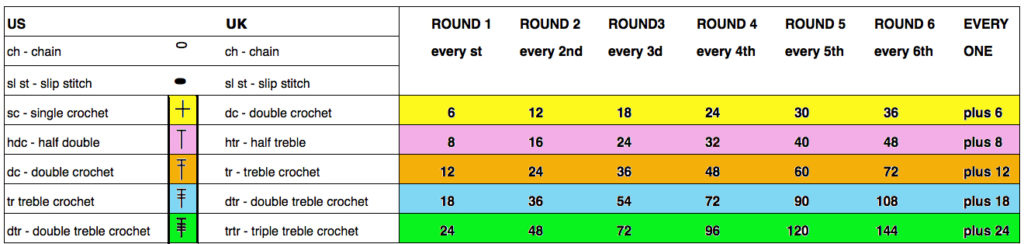

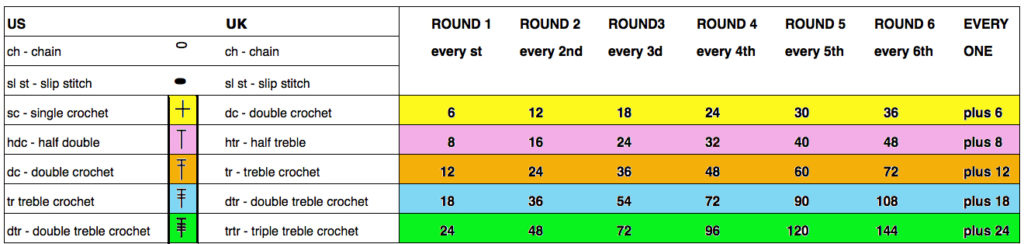

Spreadsheet programs such as Excel and Numbers have pie charts and other tools that can help visualize or even plan the work with symbols. Unlike machine knitting, both crochet and hand knitting may begin and grow from the center out or from the outside in. Calculated shaping with increases or decreases along circumferences at different points on the pie creates the desired shape. For the purposes of this discussion, I will address stitches in US terms. There are various published guidelines with some variations. The fiber content and matching gauge (if required) may need editing of the numbers, but, as starting points:

Single Crochet [sc]: Start with 6 sc and increase 6 sc in each round so that the total stitch count in each round is a multiple of 6

Half Double Crochet [hdc]: multiple of 8

Double Crochet [dc]: Multiple of 12

Treble [tr]: multiple of 16

Some symbols and number of stitches required in base rows in table form, for working from the center out:

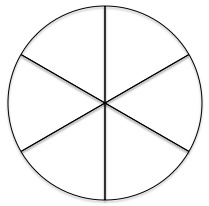

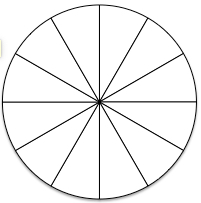

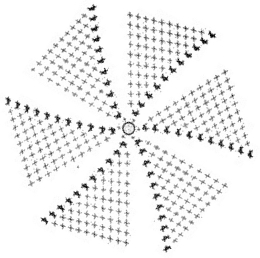

the more wedges in the pie, the smoother the circumference no matter what the method. Single crochet is worked in 6 wedges  double crochet in 12 wedges,

double crochet in 12 wedges,  wedges may be reduced to simple line segments

wedges may be reduced to simple line segments

rounds may also be created to log in and track more details

rounds may also be created to log in and track more details

adding wedge outlines before filling in symbols

adding wedge outlines before filling in symbols

single crochet worked with a slip stitch at the end of each row will produce points similar to those seen in miters in machine knitting

spirals produce a rounder shape  double crochet echoes the forms

double crochet echoes the forms

Building your own charts requires vector programs to allow for the rotation of symbols around an axis. My chart was quickly produced in Inkscape, which is free to download for both Mac and PC users. Mac users in addition will also need to download XQuartz to run the program. I created the chart with my own symbols and freeform and laid them down while viewing the grid. It turned out, however, that there are 2 published videos on how to use the program for charting crochet stitches, part 1 and part 2 by StitchesNScraps.com

Two YouTube videos on the topic: using Illustrator CS 5.1, Marnie Mac Lean’s video, and using StitchWorksSoftware. An online generator by Stitch Fiddle, and its associated video.

if donuts are the goal: find your round

An example: in single crochet, if round 3 had been completed, there would be 18 completed stitches. Chain 18, either slip stitch or continue in a spiral to match the count at that point. For round 4: increase every 4th, round 5: every fifth, round 6: every 6th, and round 7: every 7th stitch.  Different stitch heights:

Different stitch heights:

A few sites to see for crochet tutorials:

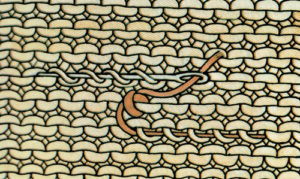

magic ring start: no chain stitches, no center hole

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLUaywX0-WE

working in spirals

http://snovej.com/archives/freeform-crochet-spiral

a nice ending

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W_sW4xX_O70

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8L_rtWt78Jw&t=32s

crocheting a flat circle in single crochet: note the start “magic circle”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8oDubbFVE3Y

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LZiCnCGP_NQ

changing colors https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U8cLufFeenU

I tend to swatch in easy-to-see colors, and “friendly” yarn, and use tools that allow moving in and out of stitches easily until I have techniques sorted out. When knitting circles in the round, things get a bit more complex, particularly if one begins introducing items such as round yokes with patterns into garments where gauge matters significantly.

Some of the same principles may be used in hand knitting. For the magic loop start with circular needles: KnitFreedom and on DPs Webs yarn

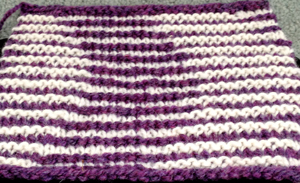

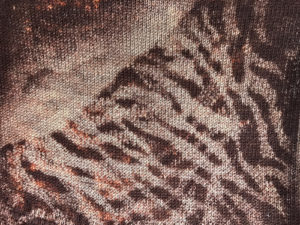

Since I am now involved in a group interested chiefly in crochet, I got curious about executing the fabric in crochet. Part of the problem is that enough texture needs to be created to be able to read the “shadows”. I tried crocheting in different parts of the chain, around the posts in the row below, and ultimately went back to afghan stitch. I had not used the latter since making blankets first for my son, and then for my grandchildren.

Since I am now involved in a group interested chiefly in crochet, I got curious about executing the fabric in crochet. Part of the problem is that enough texture needs to be created to be able to read the “shadows”. I tried crocheting in different parts of the chain, around the posts in the row below, and ultimately went back to afghan stitch. I had not used the latter since making blankets first for my son, and then for my grandchildren. tilted up

tilted up  to its side

to its side  and its rear view

and its rear view

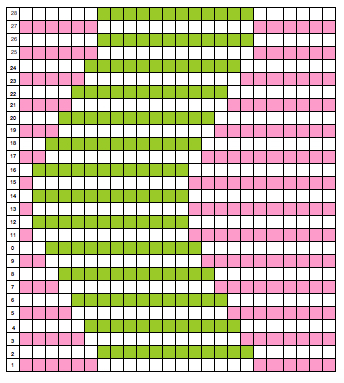

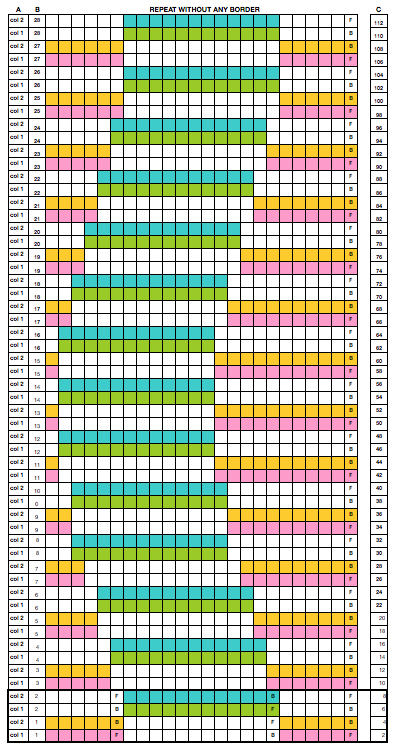

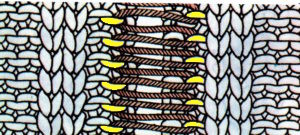

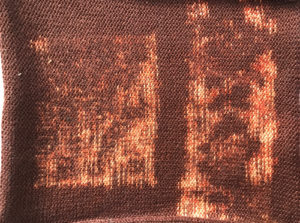

two passes are needed with each color, so here is the repeat with double length columns

two passes are needed with each color, so here is the repeat with double length columns

return pass every other row, not represented in chart

return pass every other row, not represented in chart  changing color

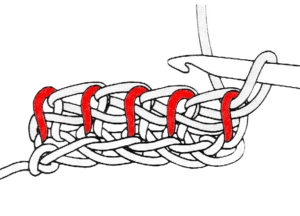

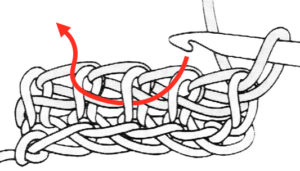

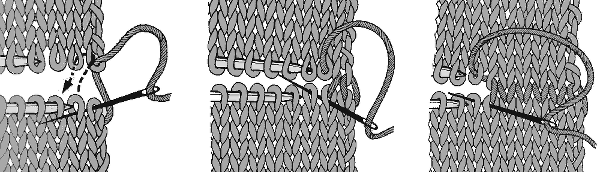

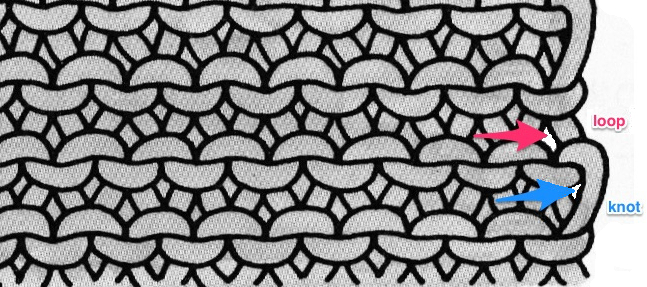

changing color  Front, vertical loop

Front, vertical loop

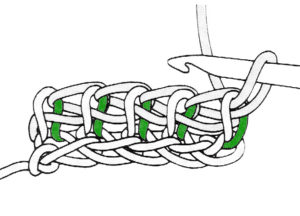

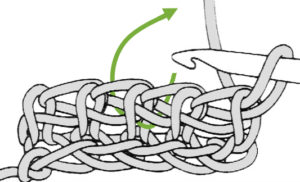

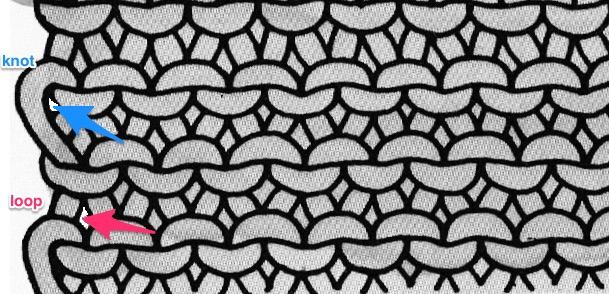

Back, vertical loop

Back, vertical loop

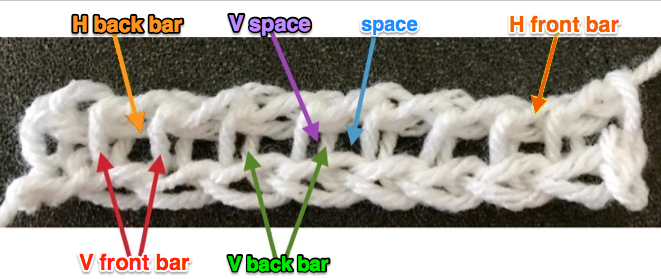

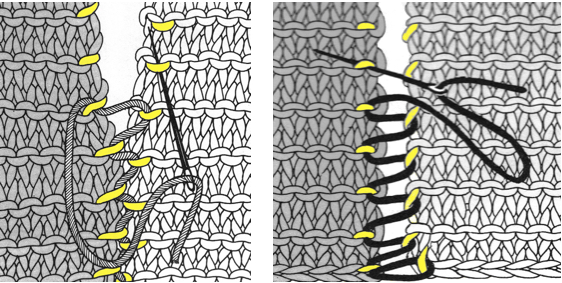

H: horizontal, V: vertical

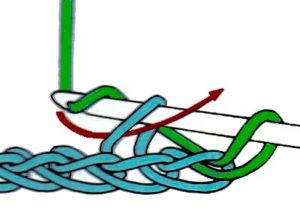

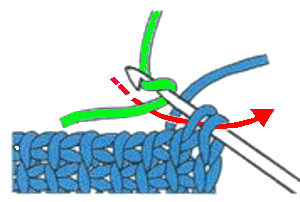

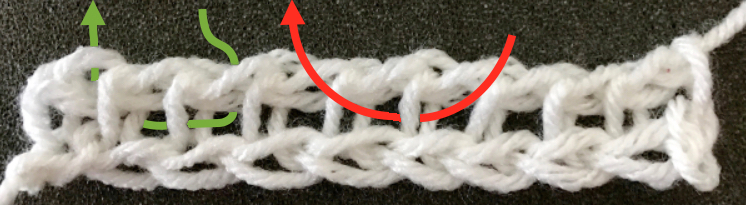

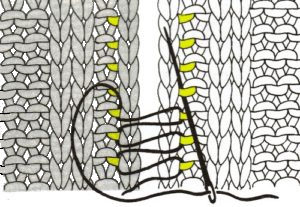

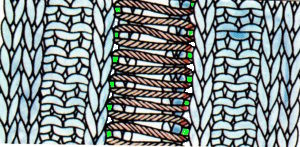

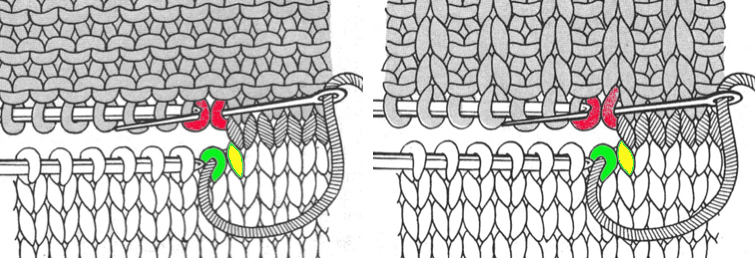

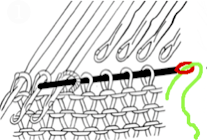

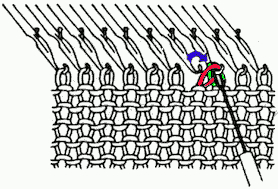

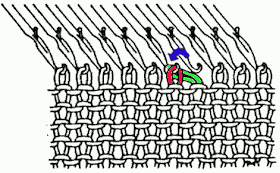

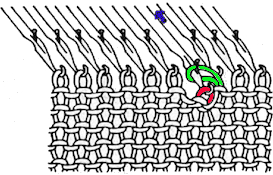

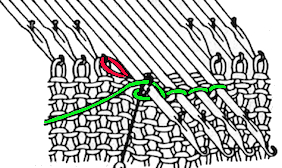

H: horizontal, V: vertical  red indicates hook entrance through the front, green for through back vertical bars respectively, prior to working the next stitch

red indicates hook entrance through the front, green for through back vertical bars respectively, prior to working the next stitch

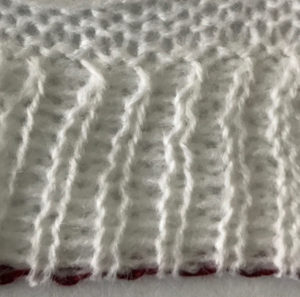

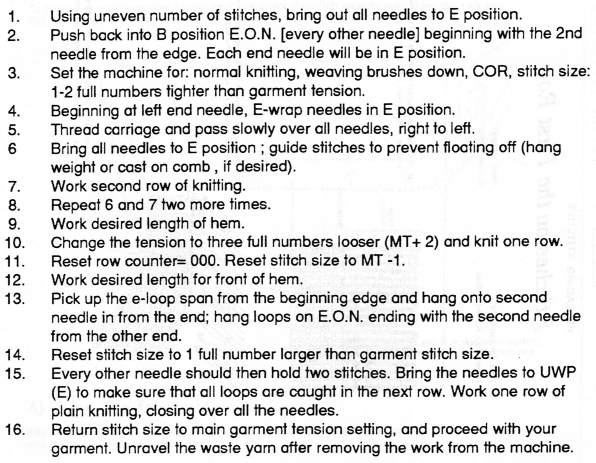

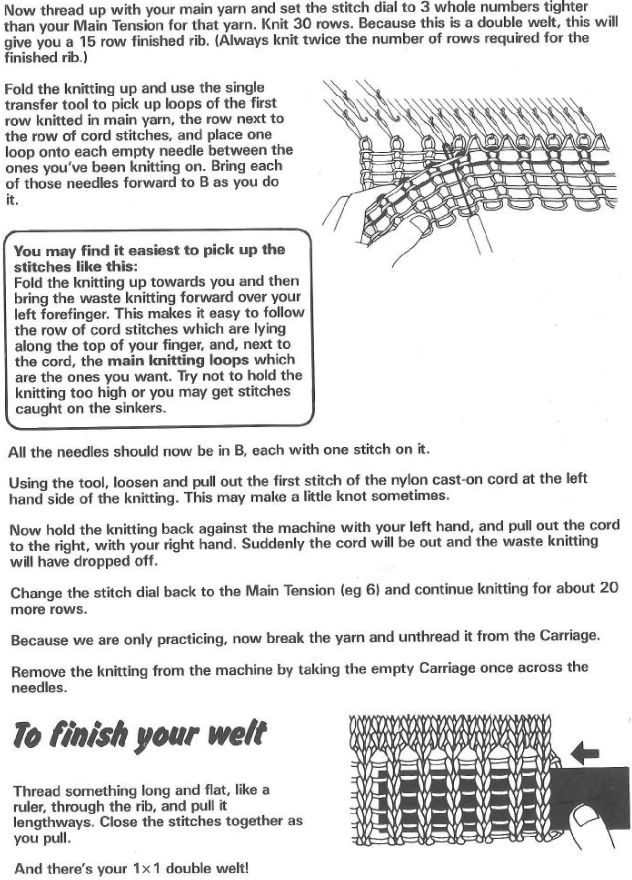

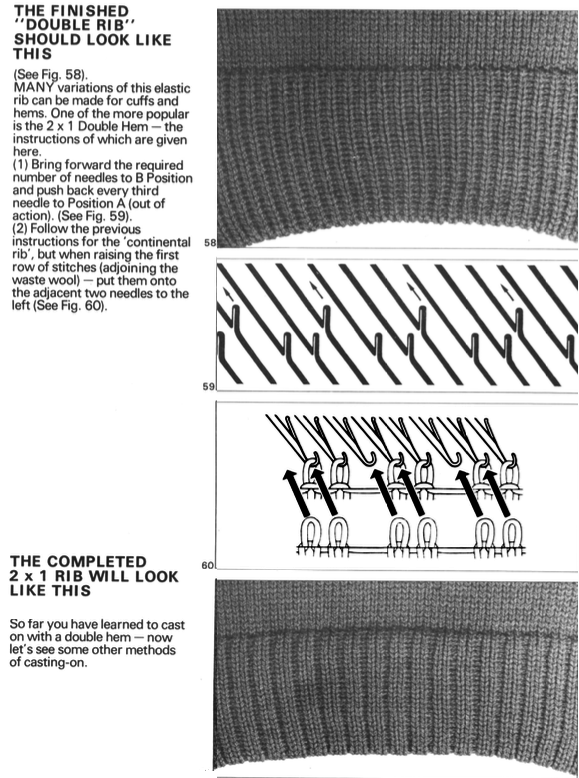

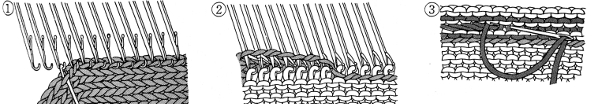

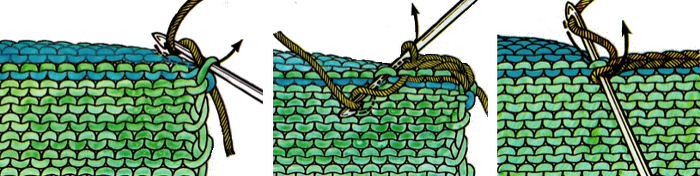

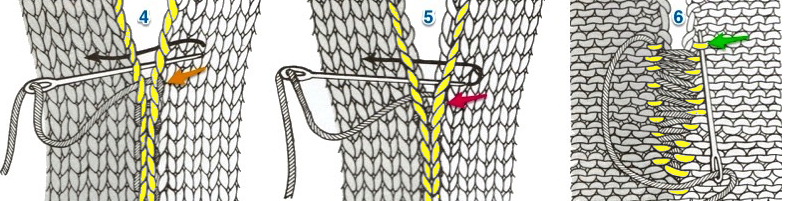

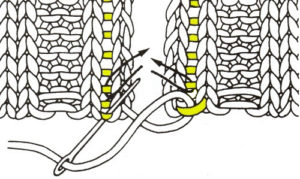

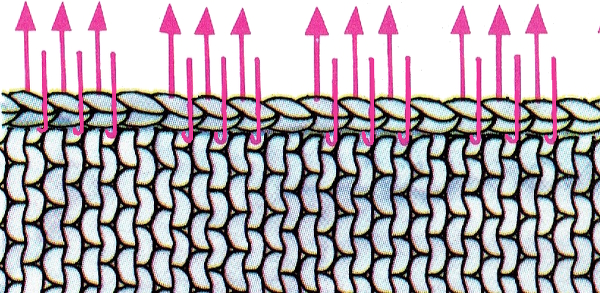

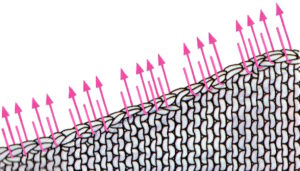

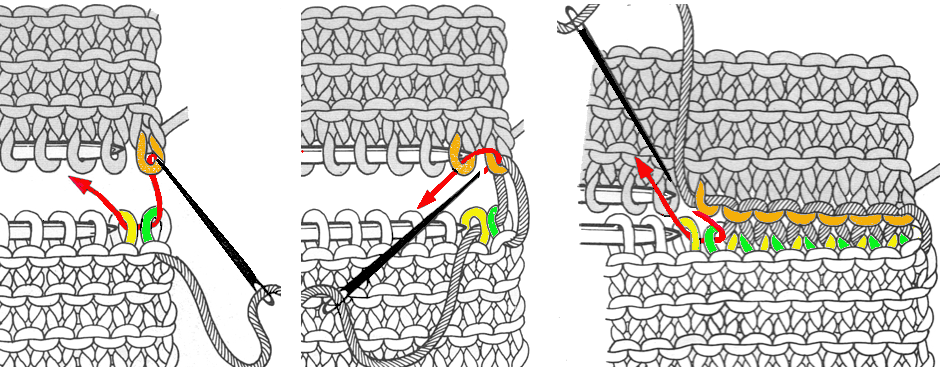

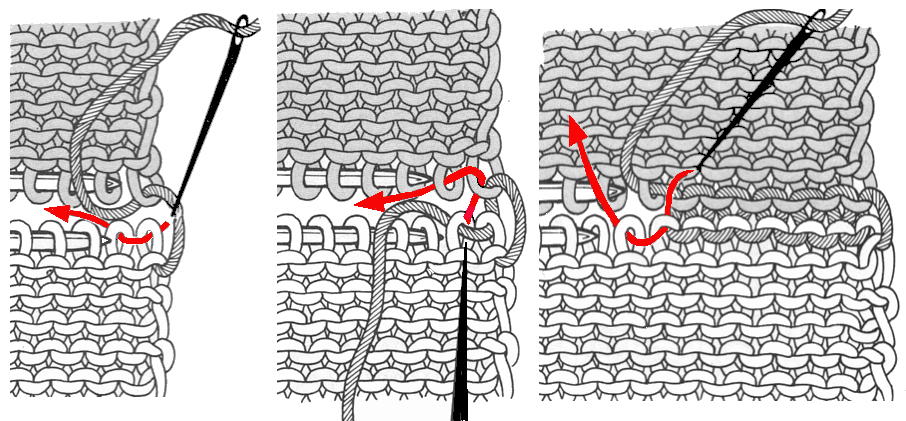

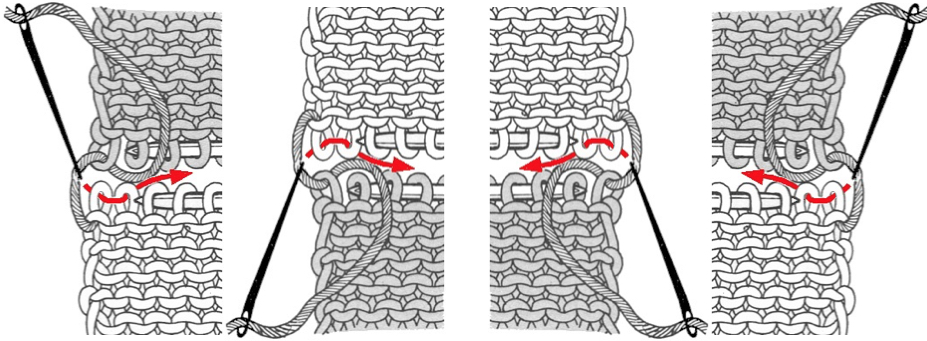

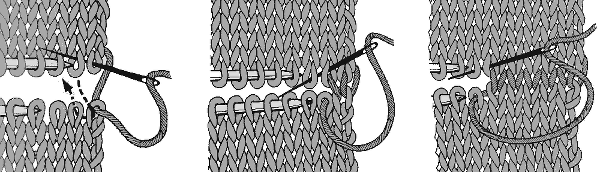

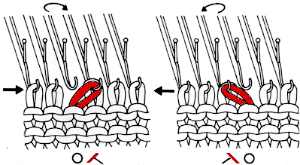

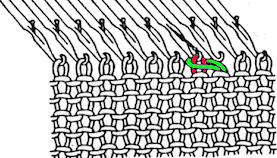

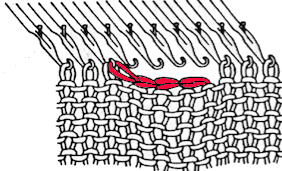

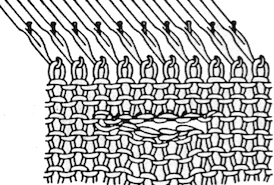

open stitches to finished hem

open stitches to finished hem

1. mattress stitch, knit side out, one full stitch away from the edge, adding a second strand of yarn to finish the join

1. mattress stitch, knit side out, one full stitch away from the edge, adding a second strand of yarn to finish the join

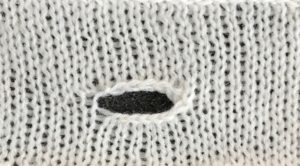

for a sense of scale before felting

for a sense of scale before felting

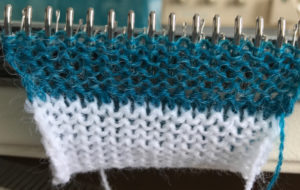

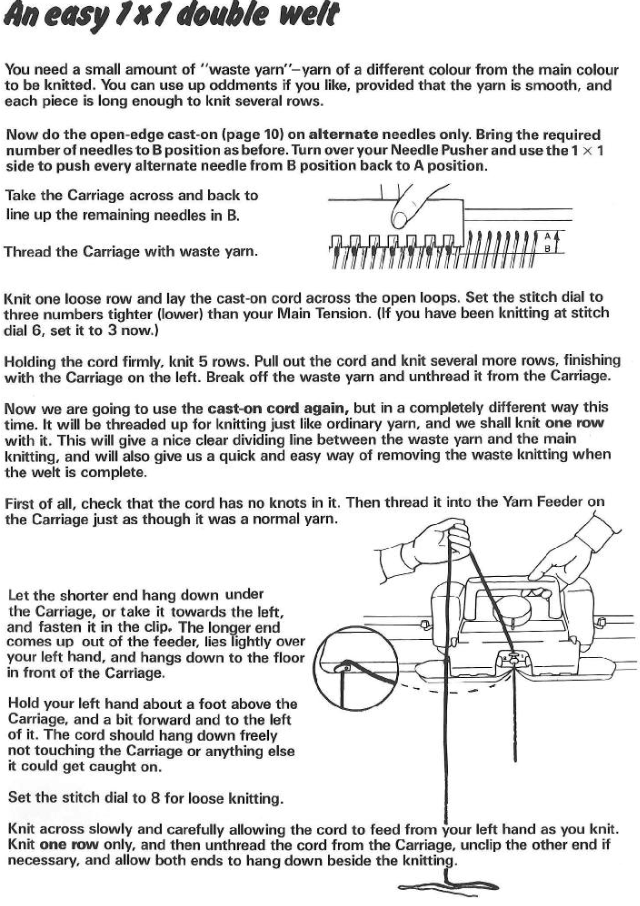

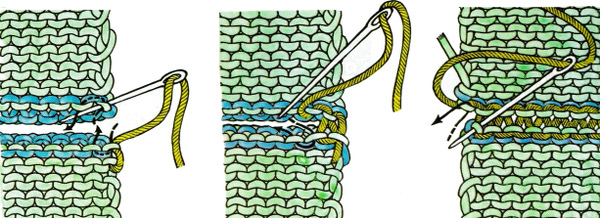

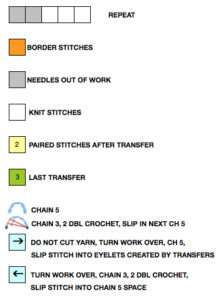

My customer handout:

My customer handout:

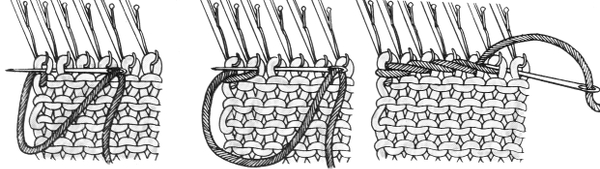

turn work over (purl side facing once again), chain 3, 2 double crochet, slip stitch into the center of chain 5 space, repeat across the knit, end with a slip stitch into last chain 5 space

turn work over (purl side facing once again), chain 3, 2 double crochet, slip stitch into the center of chain 5 space, repeat across the knit, end with a slip stitch into last chain 5 space

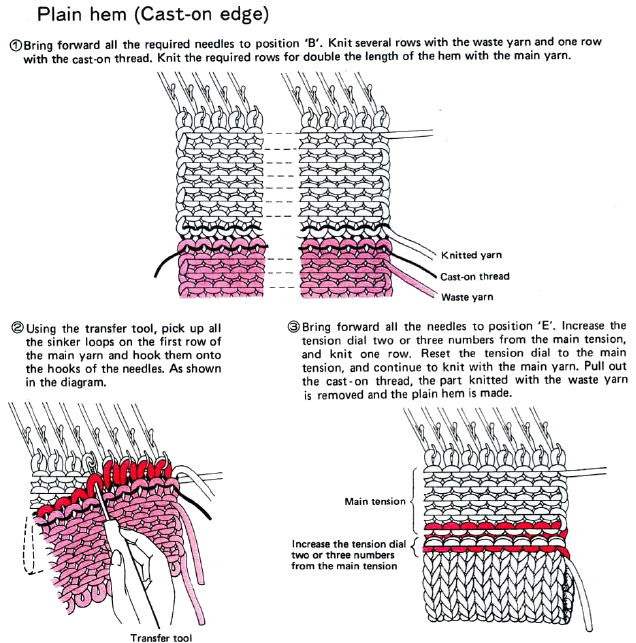

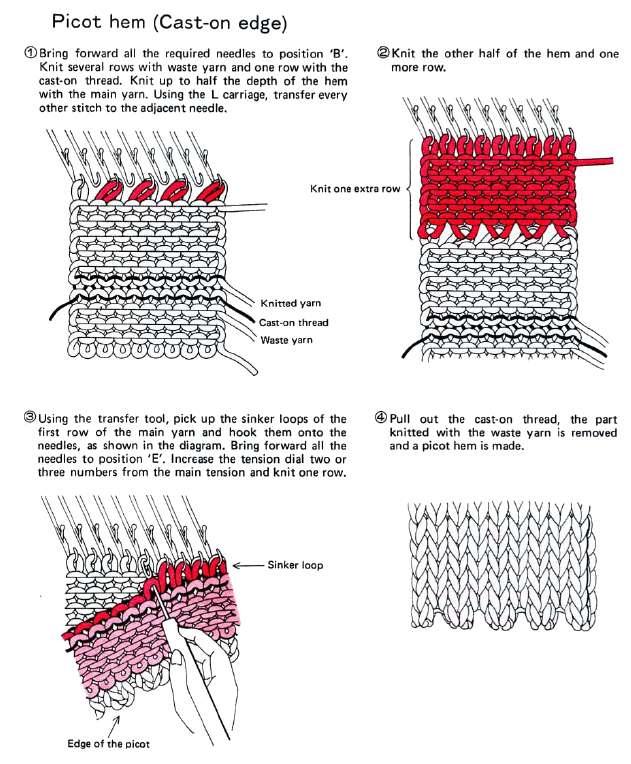

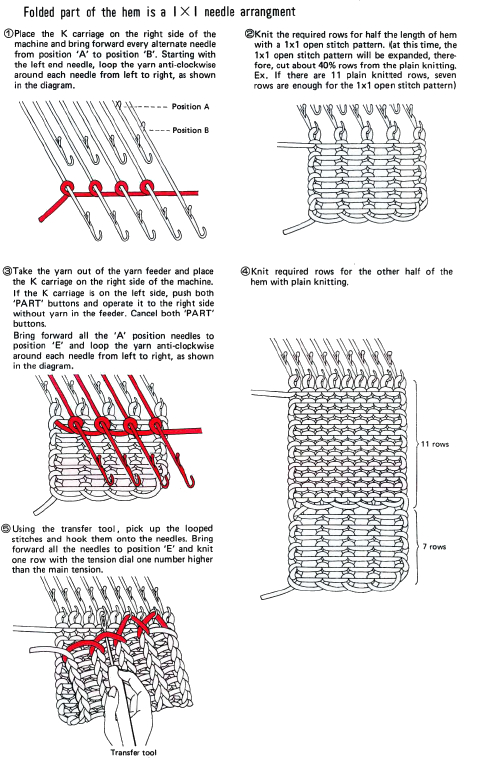

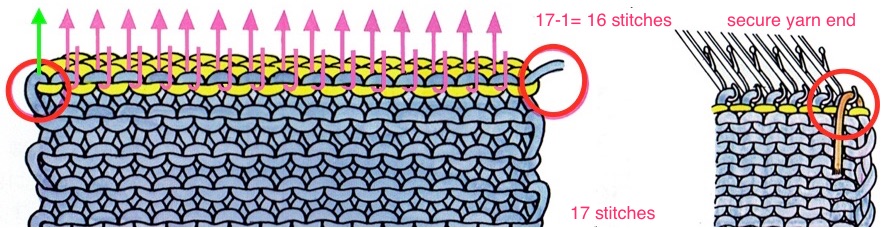

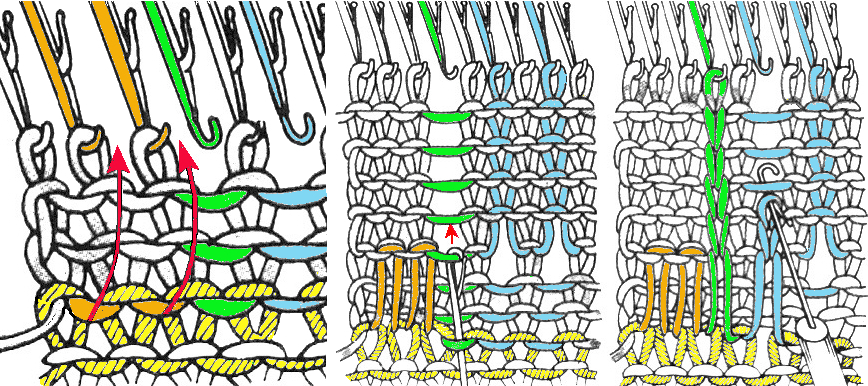

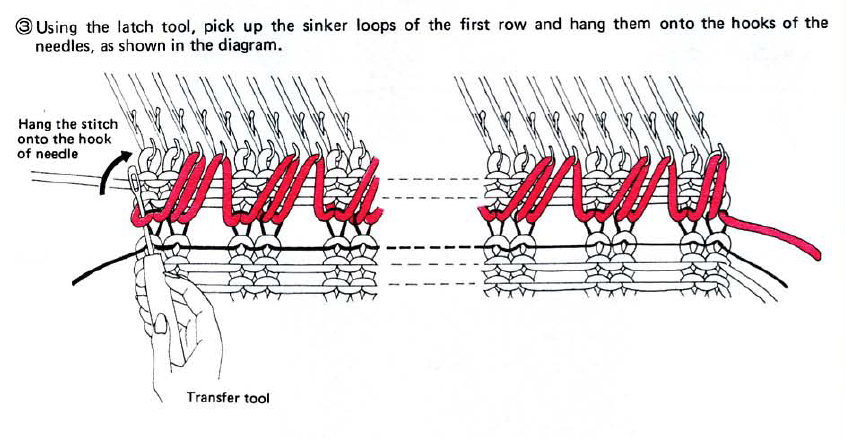

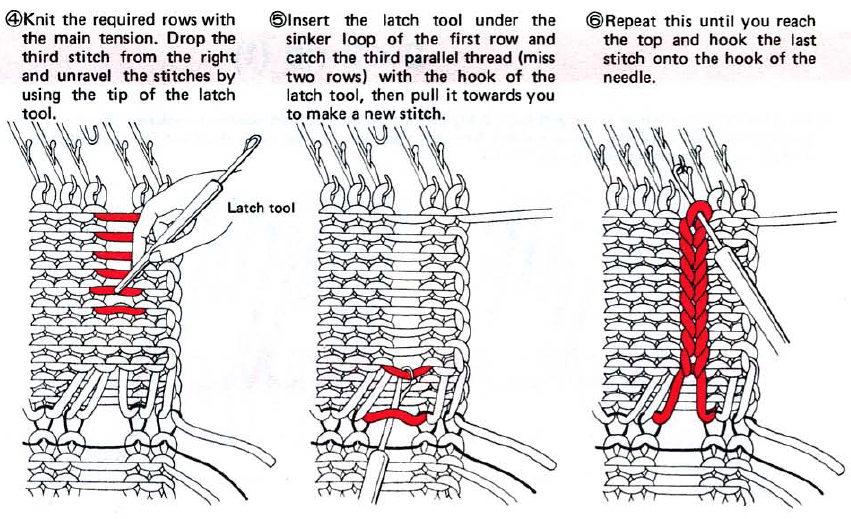

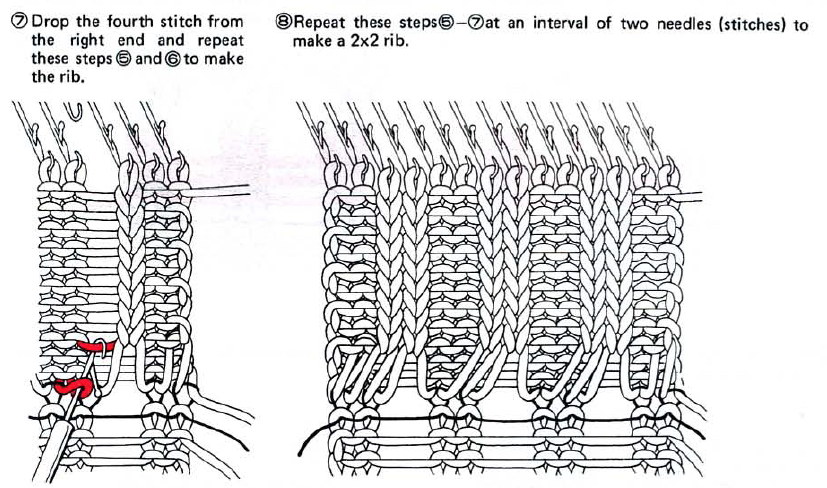

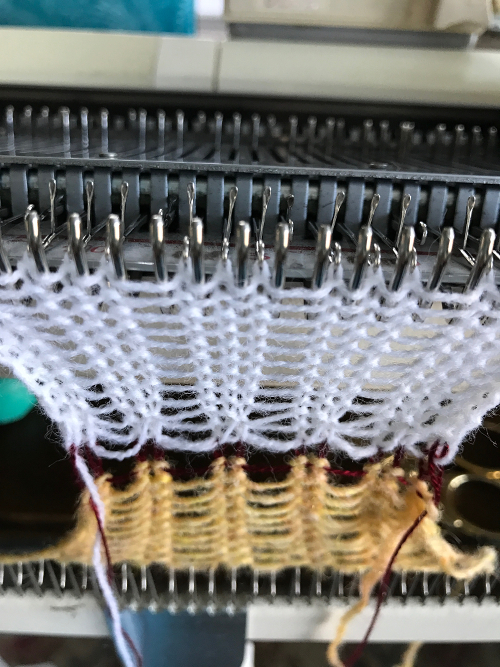

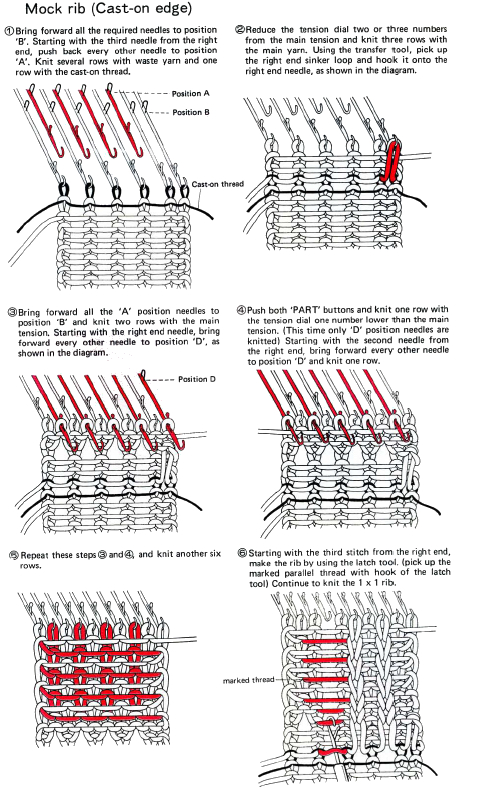

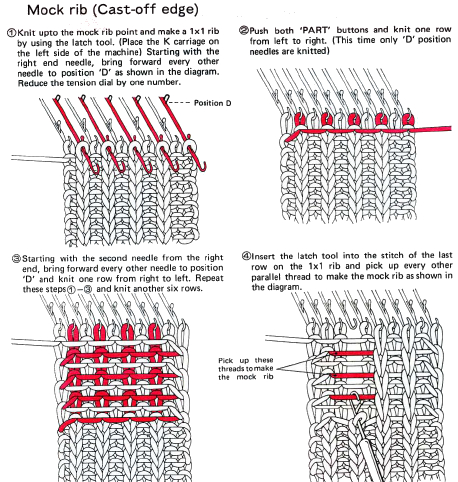

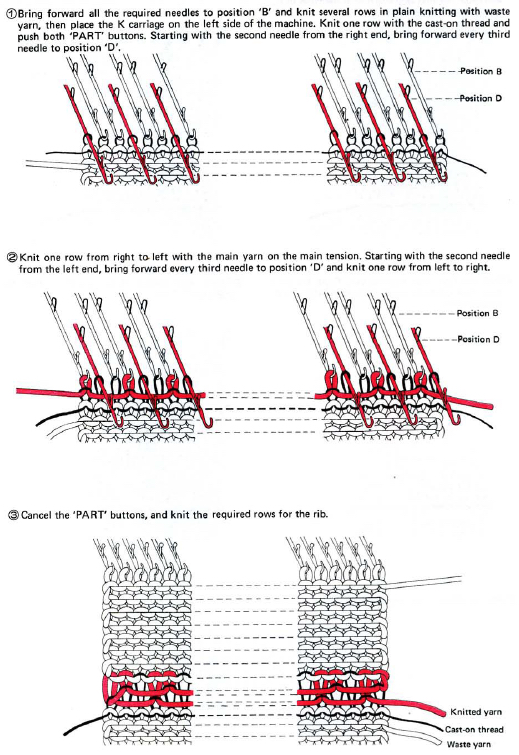

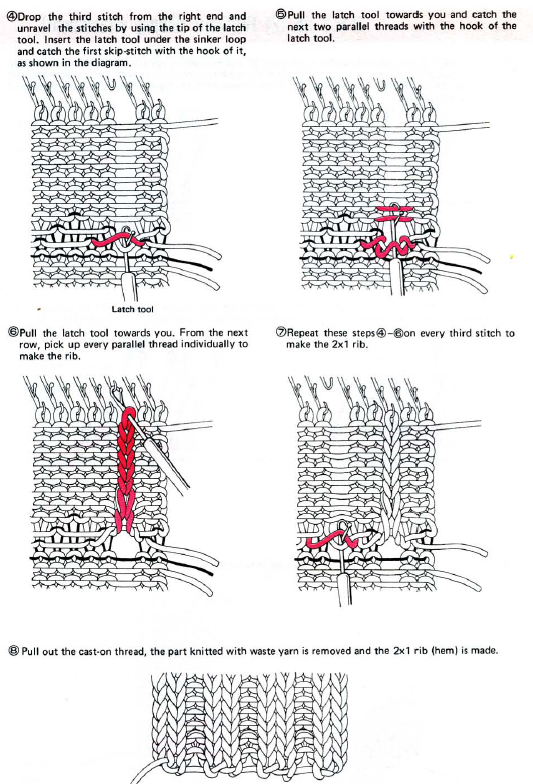

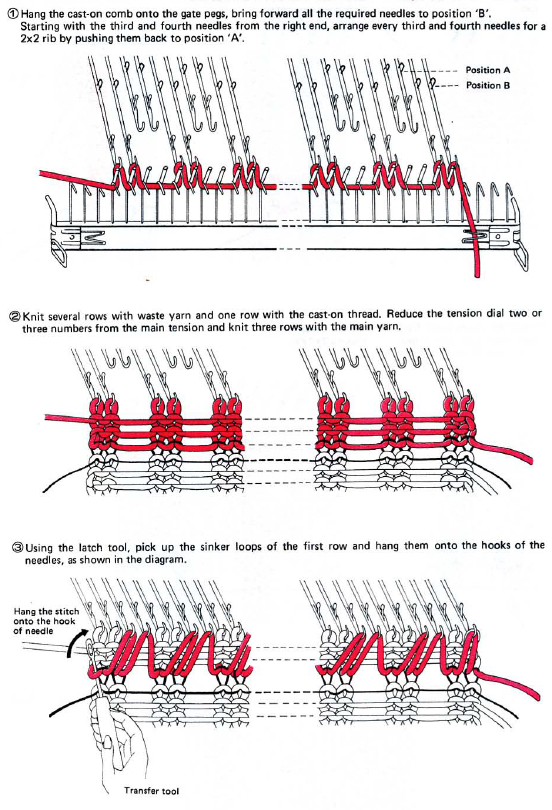

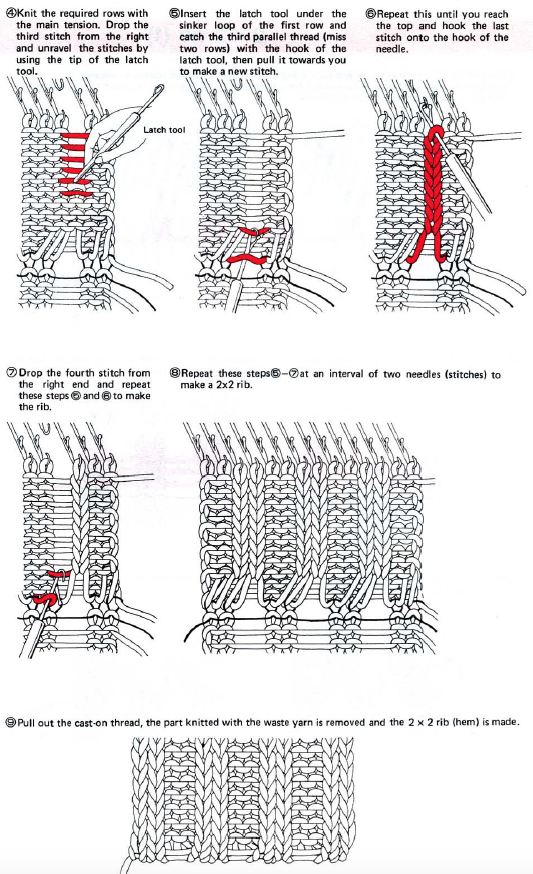

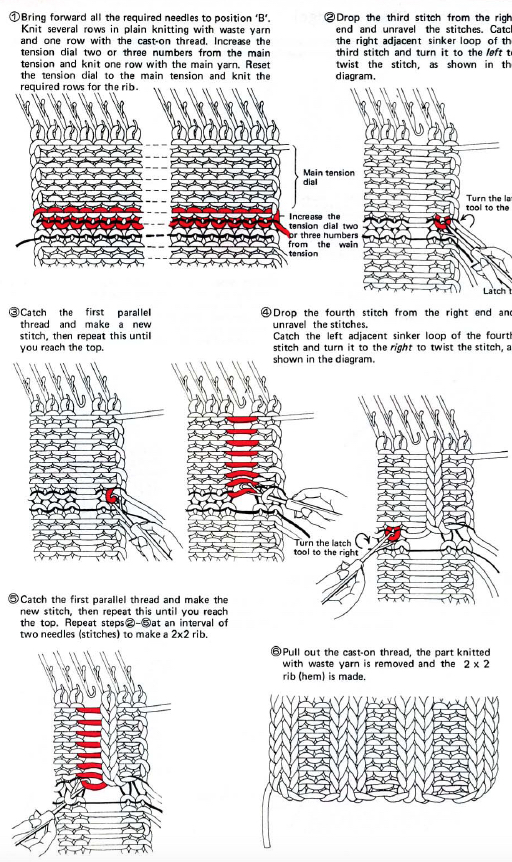

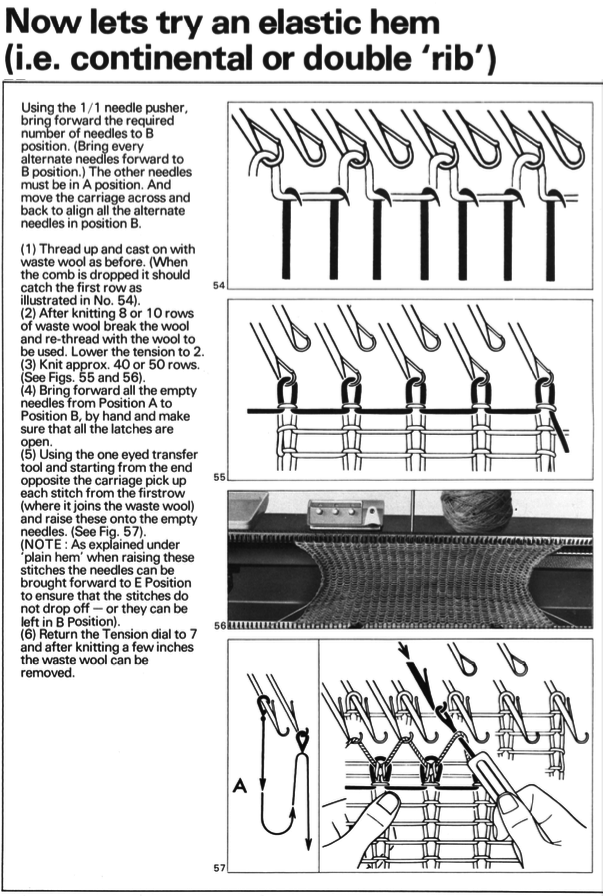

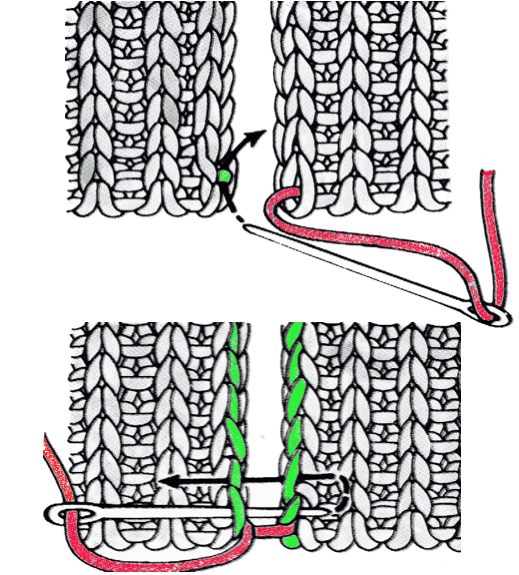

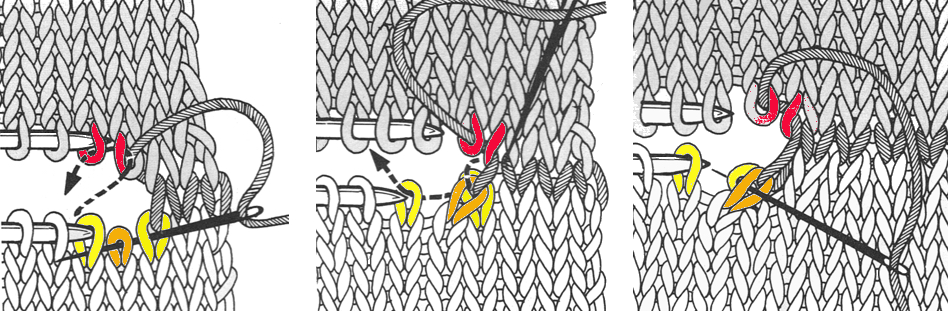

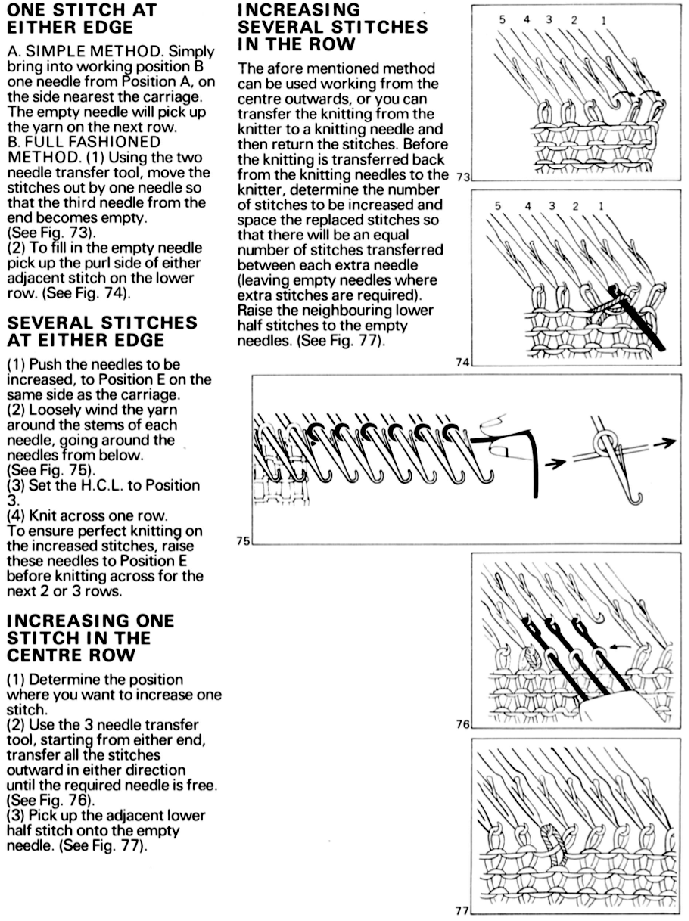

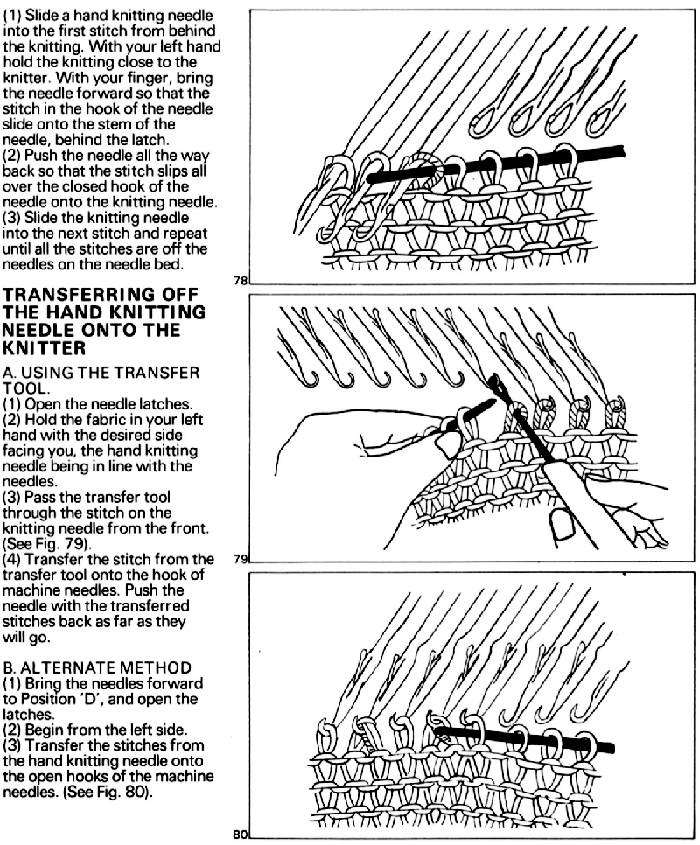

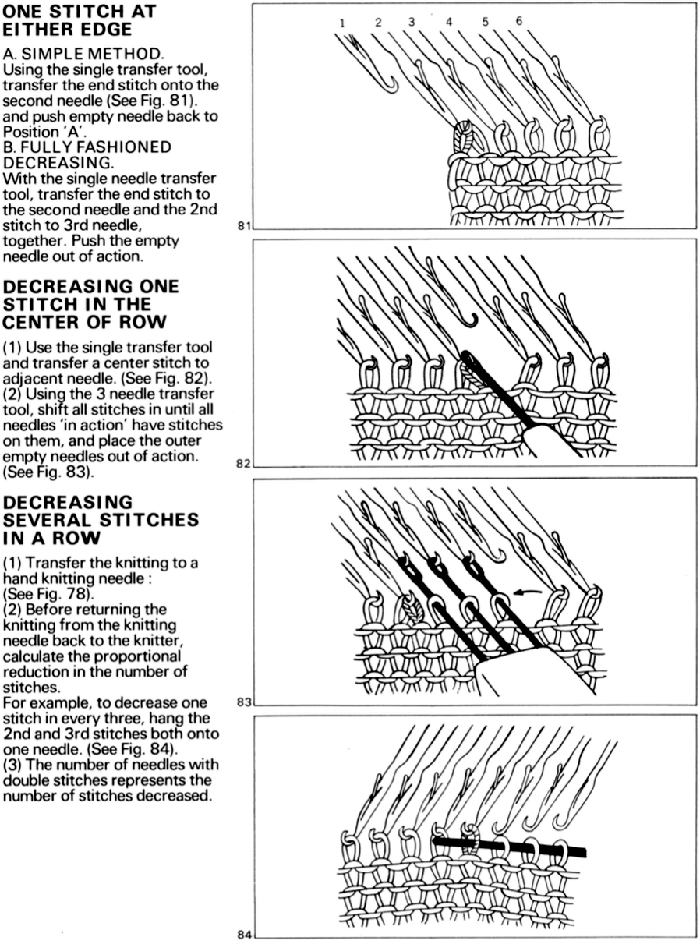

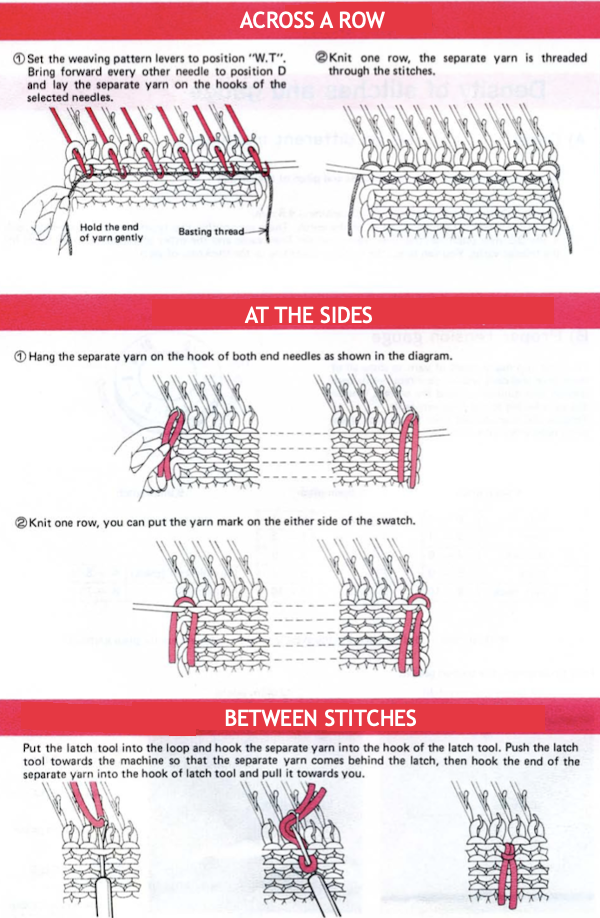

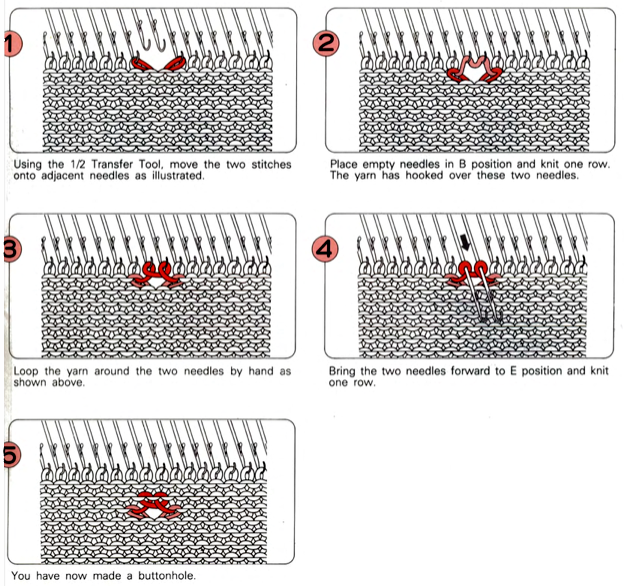

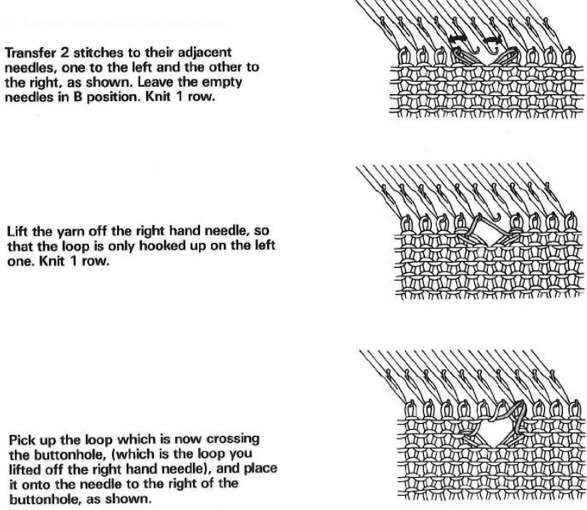

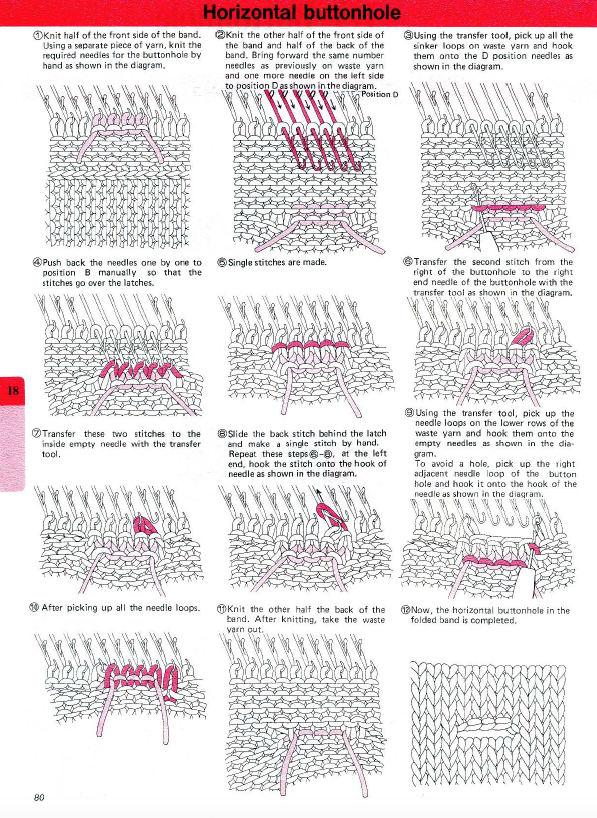

This version is from an ancient Brother manual, always test techniques on swatches using the yarns intended for the final piece

This version is from an ancient Brother manual, always test techniques on swatches using the yarns intended for the final piece