Fringes are not a personal favorite of mine on machine-knit garments in their “simplest” forms. I can recall using them rarely. Here a cut Passap version was applied to a piece made in my student days, a ruana for which I no longer have the measurements. It was composed of wool DBJ, worked in 10 panels, using a mylar sheet on a 910 for patterning, hand pieced, and is still being worn by its owner.

I made a few items with twisted strands inspired by those seen in wovens produced by my weaving friends. I have no photos of those, failed to document my work for quite a few years. One excuse was the quality of any photos I attempted, and even back in the day, professional photographers charged $180 an hour plus model fees if used. It seemed that adding the cost of such photography to limited edition runs that were planned for sale would make the wholesale price higher than the market would bear. We all make choices based on information we have at that particular time, which was long before the recent easy-to-use photo technology.

I made a few items with twisted strands inspired by those seen in wovens produced by my weaving friends. I have no photos of those, failed to document my work for quite a few years. One excuse was the quality of any photos I attempted, and even back in the day, professional photographers charged $180 an hour plus model fees if used. It seemed that adding the cost of such photography to limited edition runs that were planned for sale would make the wholesale price higher than the market would bear. We all make choices based on information we have at that particular time, which was long before the recent easy-to-use photo technology.

There now is a very good video by Diana Sullivan showing a machine knit version of twisted fringe produced on the machine.

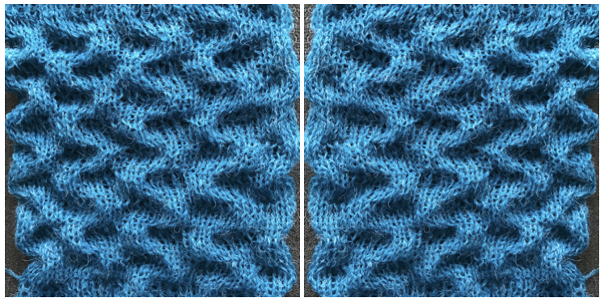

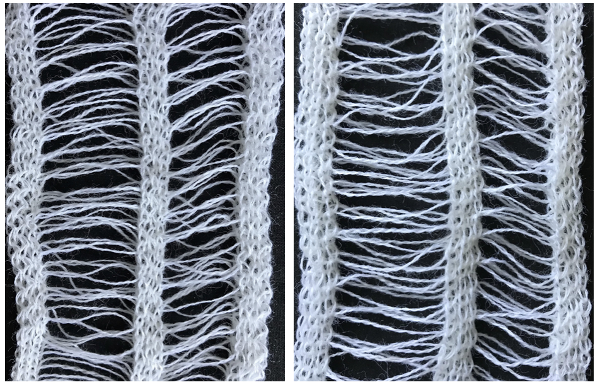

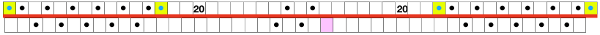

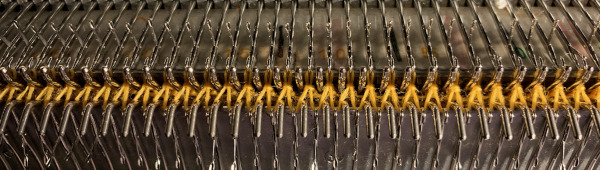

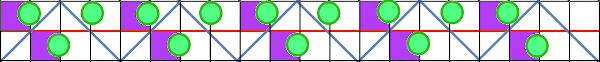

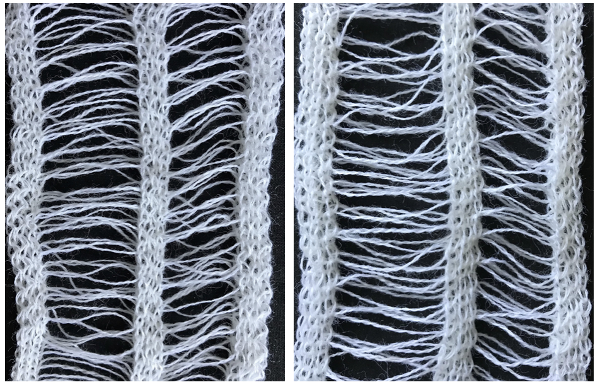

For a while, I was on an i-cord kick. I liked the look, but they were very time-consuming on production items, with lots of ends to weave in, and there was a balance to be sought between far too many to be practical and too few and skimpy to be attractive.  Here a ladder space created by needles out of work is left between vertical fair isle repeats, producing a fringe in 2 colors. The design was not planned, a standard punchcard was used for the purpose of the demo. A planned repeat would have more impact. End needle selection is on, which is usual in FI, not for most patterns with either tuck or slip stitch settings combined with needles out of work, is also true here so that a vertical line on each side of the needles out of work between repeats aids in sewing the strips together. Width is limited since the fabric will be gathered by seaming and become significantly narrower and likely turned sideways. Both sides are shown. Joining could be planned to occur only at the bottom of a piece if desired, stitching lines will be less visible if thread color matches that of the yarn

Here a ladder space created by needles out of work is left between vertical fair isle repeats, producing a fringe in 2 colors. The design was not planned, a standard punchcard was used for the purpose of the demo. A planned repeat would have more impact. End needle selection is on, which is usual in FI, not for most patterns with either tuck or slip stitch settings combined with needles out of work, is also true here so that a vertical line on each side of the needles out of work between repeats aids in sewing the strips together. Width is limited since the fabric will be gathered by seaming and become significantly narrower and likely turned sideways. Both sides are shown. Joining could be planned to occur only at the bottom of a piece if desired, stitching lines will be less visible if thread color matches that of the yarn

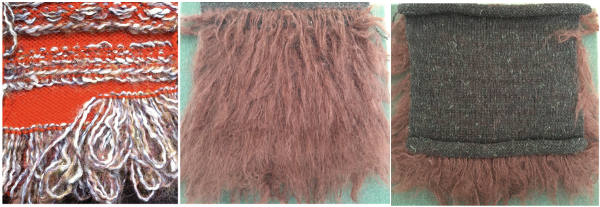

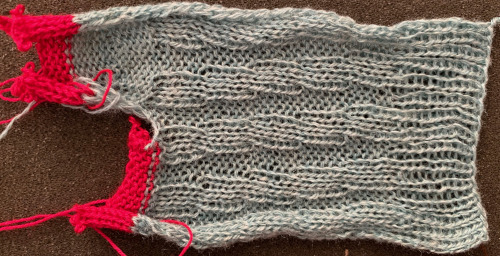

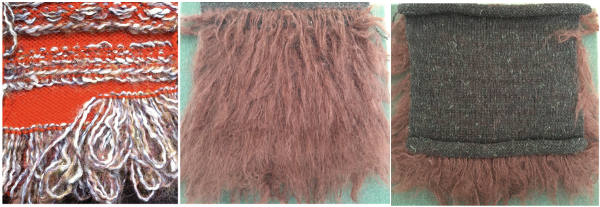

A needle in work away from the edge produces a side “fringe” followed here by felting partially, cutting the single edge stitch, and finishing the felting process

A needle in work away from the edge produces a side “fringe” followed here by felting partially, cutting the single edge stitch, and finishing the felting process

Adding thicker or multiple strands of yarns in long loops on edges, isolated areas, or all over

Adding thicker or multiple strands of yarns in long loops on edges, isolated areas, or all over  Let us not forget knit weaving with several strands of yarn, adding strips of the result as one knits, or simply hooking on strips of fake fur or thrums (the bits of yarn that litter the floor after you cut your weaving off the loom) at chosen intervals

Let us not forget knit weaving with several strands of yarn, adding strips of the result as one knits, or simply hooking on strips of fake fur or thrums (the bits of yarn that litter the floor after you cut your weaving off the loom) at chosen intervals

Finished edges on woven or lace trims, strips of fabric, and even roving along with self-made tassels may all be added at any point. Jolie tools, intended to aid in picking up dropped stitches can sometimes be helpful in picking up close to the woven edge (and pricking or piercing body parts on some days). The tool is available for both standard and bulky machines  Most often every other needle use is best. Here lace and pom trims are used, purchased fringes of all sorts could be applied the same way anywhere in the piece, joins to knit can be seen.

Most often every other needle use is best. Here lace and pom trims are used, purchased fringes of all sorts could be applied the same way anywhere in the piece, joins to knit can be seen.  A length of roving may be twisted in its center and applied as you knit. For a while mittens using it as a lining for warmth were popular. A video by Carole Wurst shows a method used in socks https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FWmH6XW_FU. Roving will felt together to varying degrees over time, as seen here in another of my ancient swatches. The “sparkle” is there as a result of using an angelica/wool blend.

A length of roving may be twisted in its center and applied as you knit. For a while mittens using it as a lining for warmth were popular. A video by Carole Wurst shows a method used in socks https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FWmH6XW_FU. Roving will felt together to varying degrees over time, as seen here in another of my ancient swatches. The “sparkle” is there as a result of using an angelica/wool blend.  the same twist in the center/ knit through method may be used with torn strips of silk or other thin fabrics, mine here are 1.5 cm. wide. Background yarn may knit fine at standard tension commonly used for it, testing will determine it and the spacing required to meet your goal

the same twist in the center/ knit through method may be used with torn strips of silk or other thin fabrics, mine here are 1.5 cm. wide. Background yarn may knit fine at standard tension commonly used for it, testing will determine it and the spacing required to meet your goal

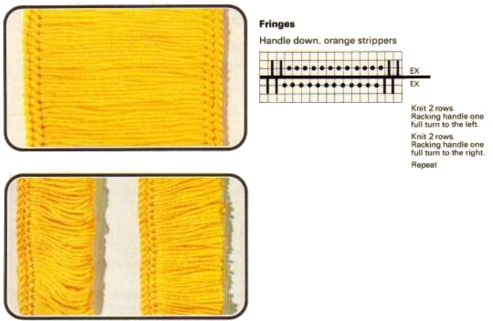

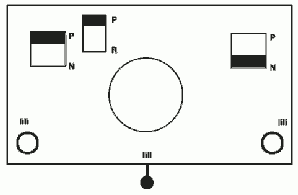

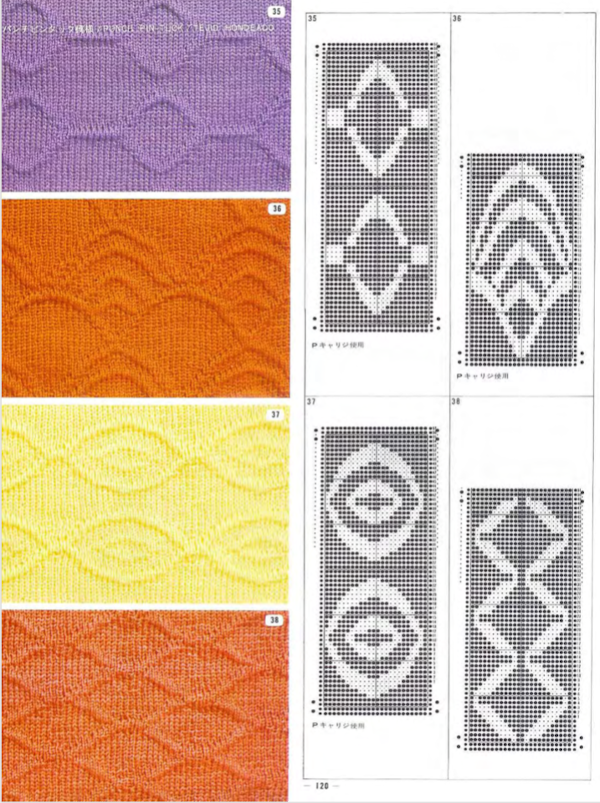

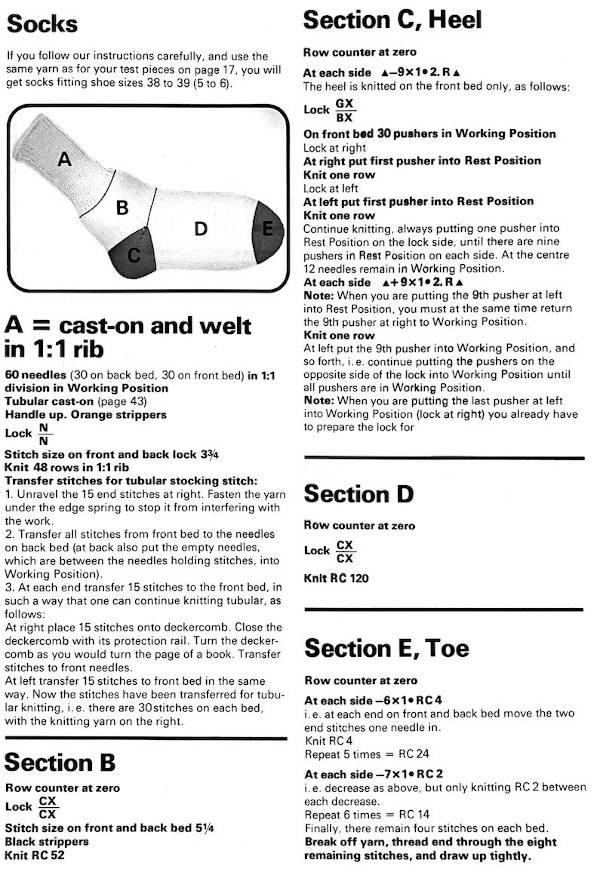

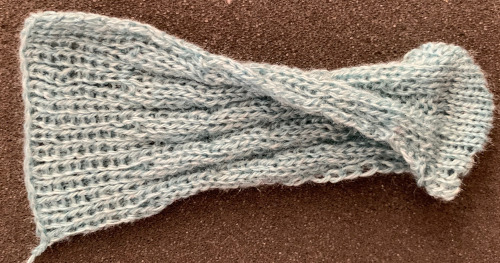

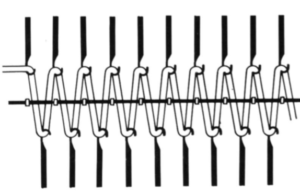

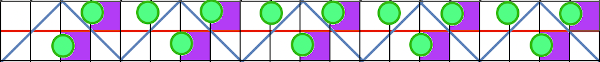

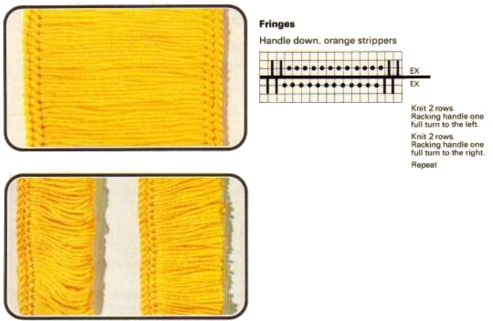

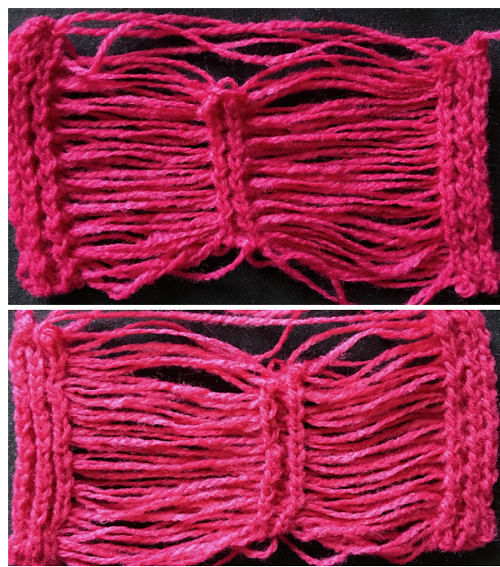

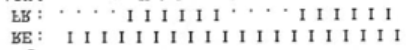

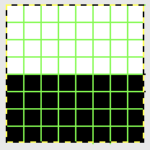

How-tos: to begin with, this is the “passap” version illustrated in the Duo Manual. One may choose wider knit bands between the floats that will be cut or folded over and doubled up

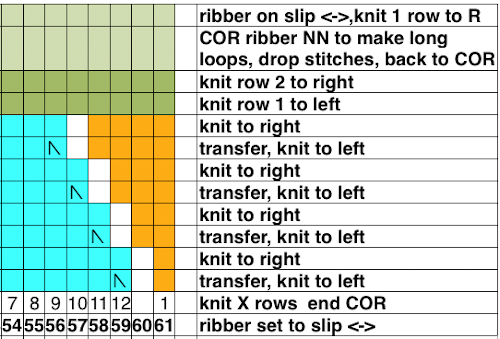

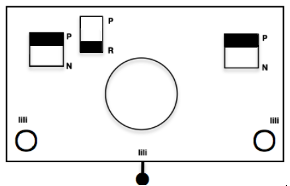

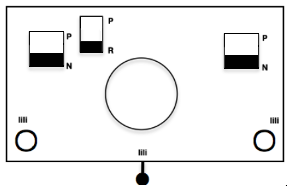

The thickness of the yarn chosen is of critical importance. When I first attempted to knit a version of it on my 930 I encountered problems. To start with, I kept dropping off the stitches on one side or the other. I checked the ribber alignment, proper placement of the cast on comb, switched ribbers, and carriages, and continued to have problems. After all that, the solution turned out to be simply adding another 4 stitches (2 on each bed) toward the center of the piece (I did not count). Here I used a 2/24 which obviously does not have enough body to use as an edging. The Brother equivalent for the Duo setting is half fisherman rib, where one carriage knits in one direction, tucks in the other on every needle for every 2 rows knit, while the other bed’s carriage does the same, but in opposite directions. I used 3 needles on each side rather than 2 as in the Duo repeat, starting with the first needle in work on the left on the ribber, the last needle in work on the right on the top bed. One may begin to knit on either side, but when manually setting the cam buttons lead with settings so that first stitch knits as it moves to the opposite side. Using waste yarn at the start of the piece will produce a better cast on edge for the trim. Operating from the right:

The thickness of the yarn chosen is of critical importance. When I first attempted to knit a version of it on my 930 I encountered problems. To start with, I kept dropping off the stitches on one side or the other. I checked the ribber alignment, proper placement of the cast on comb, switched ribbers, and carriages, and continued to have problems. After all that, the solution turned out to be simply adding another 4 stitches (2 on each bed) toward the center of the piece (I did not count). Here I used a 2/24 which obviously does not have enough body to use as an edging. The Brother equivalent for the Duo setting is half fisherman rib, where one carriage knits in one direction, tucks in the other on every needle for every 2 rows knit, while the other bed’s carriage does the same, but in opposite directions. I used 3 needles on each side rather than 2 as in the Duo repeat, starting with the first needle in work on the left on the ribber, the last needle in work on the right on the top bed. One may begin to knit on either side, but when manually setting the cam buttons lead with settings so that first stitch knits as it moves to the opposite side. Using waste yarn at the start of the piece will produce a better cast on edge for the trim. Operating from the right:

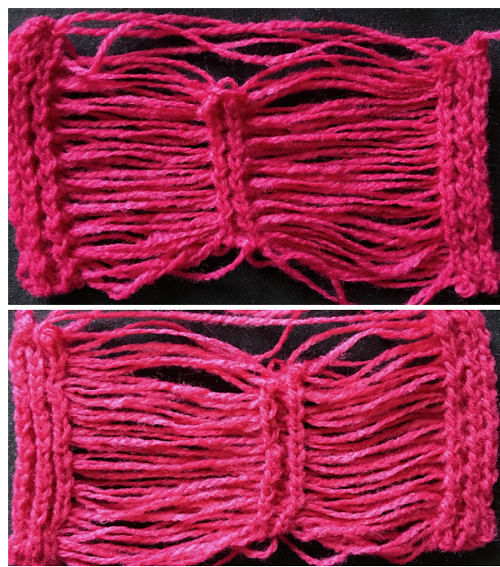

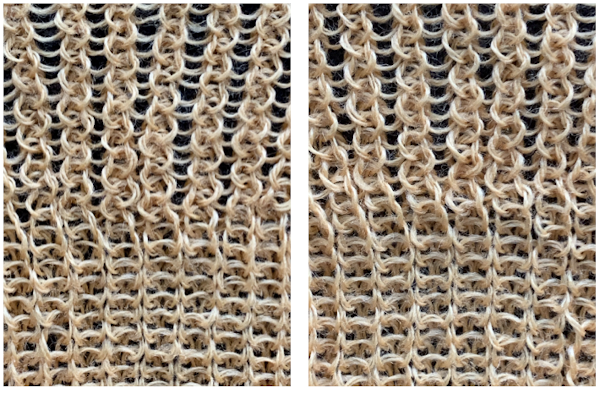

A 2/11.5 acrylic provided more of a tension adjustment challenge but made for a better fringe.

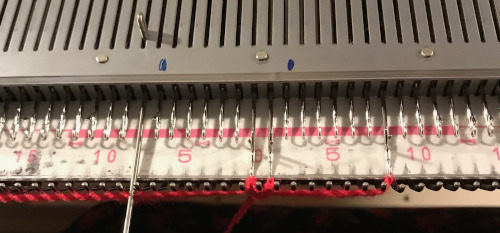

A 2/11.5 acrylic provided more of a tension adjustment challenge but made for a better fringe. The first and last 3 stitches on either side were transferred to the top bed and bound off, the center stitches were not, allowing them to be unraveled if desired ie in case the fringe is to be folded in half. Those extra center stitches also provide a guide for cutting either down their center (bottom of photo) or on either side of them (toward the top). I found the latter method to produce a cleaner cut line

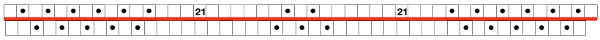

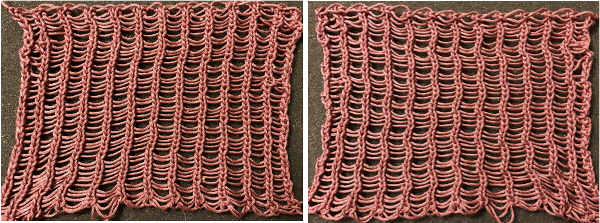

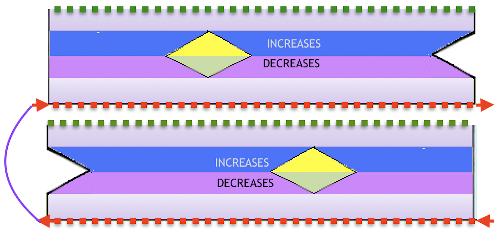

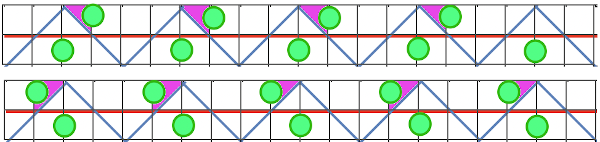

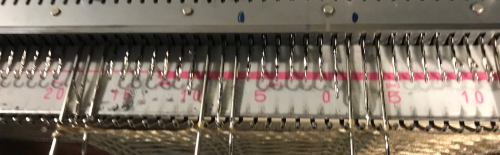

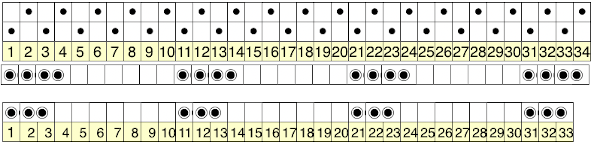

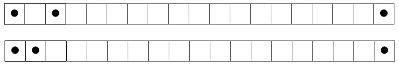

The first and last 3 stitches on either side were transferred to the top bed and bound off, the center stitches were not, allowing them to be unraveled if desired ie in case the fringe is to be folded in half. Those extra center stitches also provide a guide for cutting either down their center (bottom of photo) or on either side of them (toward the top). I found the latter method to produce a cleaner cut line Suggestions for going wider with racked half fisherman rib on Japanese machines: begin with needle arrangement below, out of work needles can be as many as needed, set up and cast on with preferred racking position ie on 5, knit several rows in waste yarn making any adjustments needed so stitches knit are formed properly, weigh appropriately.

Suggestions for going wider with racked half fisherman rib on Japanese machines: begin with needle arrangement below, out of work needles can be as many as needed, set up and cast on with preferred racking position ie on 5, knit several rows in waste yarn making any adjustments needed so stitches knit are formed properly, weigh appropriately.  Add needles on the main bed and remove one on the ribber

Add needles on the main bed and remove one on the ribber Continue the test including in pattern, switch to a couple of rows of plain knitting and end with one knit row using ravel cord in a contrasting color. Cast on for fringe, knit 2 rows. Set for tuck rib, knit 2 rows, rack to position 4, knit 2 rows, rack to position 5, continue racking for the desired length, end with 2 knit rows and bind off or scrap off in case any additional length might be needed. When knitting lengths of trim, ending the piece on open stitches and waste knitting will give one the opportunity to either unravel or add more rows if needed.

Continue the test including in pattern, switch to a couple of rows of plain knitting and end with one knit row using ravel cord in a contrasting color. Cast on for fringe, knit 2 rows. Set for tuck rib, knit 2 rows, rack to position 4, knit 2 rows, rack to position 5, continue racking for the desired length, end with 2 knit rows and bind off or scrap off in case any additional length might be needed. When knitting lengths of trim, ending the piece on open stitches and waste knitting will give one the opportunity to either unravel or add more rows if needed.

Knitting fringes with a center band and cutting side edges will form variations on “feathers”. Pretend “hairpin lace ” produced on the knitting machine also uses related ideas.

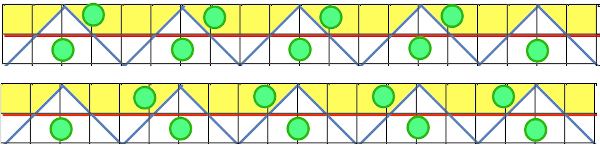

An aside tip: if knitting pieces with strips of stocking stitch between ladder spaces often the side edges of the vertical knit columns will not hold and become wider and distorted. Using a single stitch in from each side of the columns on the ribber as well and racking one to left, one to the right from the original position every one or 2 rows will stabilize them. This swatch was knit in a very slippery rayon/cotton blend over 20 years ago using single neighboring stitches on both beds the edge that holds the fringe together is to be very narrow (or even added as one continues to knit) and one wishes to work on the single bed there are several options. With 4-ply and a “matching color” 2 ply I began with the top needle arrangement, and then switched to the one below it, knitting on a 4.5 mm machine.

the edge that holds the fringe together is to be very narrow (or even added as one continues to knit) and one wishes to work on the single bed there are several options. With 4-ply and a “matching color” 2 ply I began with the top needle arrangement, and then switched to the one below it, knitting on a 4.5 mm machine.  A permanent cast-on needs to take place in the preferred method over needles in work knit 2 rows. The stitch on the second needle from the left is going to want to stretch and tends not to be stable. To reduce that happening, there are 2 options involving the second strand of yarn. Here using a 2 ply helps serve that purpose and keeps the fringed strands closer together. The slower method is to remove the second stitch from the left on a tool after every 2 rows knit, then bring the separate yarn strand behind the now empty needle first from the right, then in turn from the left, returning the removed stitch to the machine, knitting 2 rows. I found that too slow for my patience, switched to just laying the second strand over needles before knitting each pair of rows, and decided to eliminate the out of work needle on the left side, moving the second stitch in work to its left.

A permanent cast-on needs to take place in the preferred method over needles in work knit 2 rows. The stitch on the second needle from the left is going to want to stretch and tends not to be stable. To reduce that happening, there are 2 options involving the second strand of yarn. Here using a 2 ply helps serve that purpose and keeps the fringed strands closer together. The slower method is to remove the second stitch from the left on a tool after every 2 rows knit, then bring the separate yarn strand behind the now empty needle first from the right, then in turn from the left, returning the removed stitch to the machine, knitting 2 rows. I found that too slow for my patience, switched to just laying the second strand over needles before knitting each pair of rows, and decided to eliminate the out of work needle on the left side, moving the second stitch in work to its left.  The single stitch on the far right of the chart need not be bound off. There will be 2 options after the work is off the machine. One is to unravel the single stitch column on the far right if loops are the goal, or cut it off, leaving a fairly good trimmed edge here, and what, in this yarn, appeared to me to be an acceptable edging. The 2 edge stitches on the left in my swatch did roll, making a very tight edge. Adjusting the tension used to change that effect would be another choice. Yarn use and personal taste contribute to a range of “successful” results when using any of these techniques.

The single stitch on the far right of the chart need not be bound off. There will be 2 options after the work is off the machine. One is to unravel the single stitch column on the far right if loops are the goal, or cut it off, leaving a fairly good trimmed edge here, and what, in this yarn, appeared to me to be an acceptable edging. The 2 edge stitches on the left in my swatch did roll, making a very tight edge. Adjusting the tension used to change that effect would be another choice. Yarn use and personal taste contribute to a range of “successful” results when using any of these techniques.

This version creates a true i-cord edging on one side, and produces a double fringe. Begin cast on with 5 stitches on one side, 1 on the opposite side to accommodate the desired width. As I knit my sample, I added a second stitch on that same side to make for an easier, more stable cutting line. Any changes in tension will affect the width and rigidity of the i-cord, and more markedly any stitches on the opposite side, and the length of the cut loops. As when knitting any slip stitch cords, the tension needs to be tightened by at least 2 numbers from that used in knitting the same yarn in stocking stitch. The carriage is set to slip in one direction, knit in the other, producing a float the width of the knit. Cast on. Beginning with COR knit one row to left, set the carriage to knit in one direction only (I happened to use the right part button, either can work). The process that draws the left side vertical column together into a cord : * transfer the fourth stitch from the left onto the fifth, move both stitches back onto the just emptied fourth needle, leave the fifth needle in work, “knit” 2 rows*. Technically, the 2 passes of the knit carriage to and from the left will produce only one knit row. I used the 2/11.5 acrylic, on the skimpy side. Thin yarns may be plied for the best effect. Here that second stitch has been added on the right, a few rows have been plain-knit.

This version creates a true i-cord edging on one side, and produces a double fringe. Begin cast on with 5 stitches on one side, 1 on the opposite side to accommodate the desired width. As I knit my sample, I added a second stitch on that same side to make for an easier, more stable cutting line. Any changes in tension will affect the width and rigidity of the i-cord, and more markedly any stitches on the opposite side, and the length of the cut loops. As when knitting any slip stitch cords, the tension needs to be tightened by at least 2 numbers from that used in knitting the same yarn in stocking stitch. The carriage is set to slip in one direction, knit in the other, producing a float the width of the knit. Cast on. Beginning with COR knit one row to left, set the carriage to knit in one direction only (I happened to use the right part button, either can work). The process that draws the left side vertical column together into a cord : * transfer the fourth stitch from the left onto the fifth, move both stitches back onto the just emptied fourth needle, leave the fifth needle in work, “knit” 2 rows*. Technically, the 2 passes of the knit carriage to and from the left will produce only one knit row. I used the 2/11.5 acrylic, on the skimpy side. Thin yarns may be plied for the best effect. Here that second stitch has been added on the right, a few rows have been plain-knit.  This shows the length of the slipped row, and that a loop is formed on the return to the other side on the empty but in work needle # 5.

This shows the length of the slipped row, and that a loop is formed on the return to the other side on the empty but in work needle # 5.  The transfers from needle 4 to 5 and back have been made, leaving the empty needle 5 in work.

The transfers from needle 4 to 5 and back have been made, leaving the empty needle 5 in work.  At the top of the piece, I transferred and doubled up the stitches on left, bound them off, and the yarn end(s) can be woven back into the cord.

At the top of the piece, I transferred and doubled up the stitches on left, bound them off, and the yarn end(s) can be woven back into the cord.  The side with the transfers is the “public” one, the finished fringe is usually hand sewn on, but it may also be used to cast on or be applied to several places in the knit both close together or at various intervals. Tension changes may be observed viewing from left to right, as well as the difference in length of loops as opposed to after the cutaway edge. The third stitch in work on the right may make for a more stable cutting line if looser tensions are preferred. Because the sinker plate used on the single bed has brushes and wheels in use, the width of the fringe can be considerable, without having to be concerned about stabilizing the center as it is when working on the double bed.

The side with the transfers is the “public” one, the finished fringe is usually hand sewn on, but it may also be used to cast on or be applied to several places in the knit both close together or at various intervals. Tension changes may be observed viewing from left to right, as well as the difference in length of loops as opposed to after the cutaway edge. The third stitch in work on the right may make for a more stable cutting line if looser tensions are preferred. Because the sinker plate used on the single bed has brushes and wheels in use, the width of the fringe can be considerable, without having to be concerned about stabilizing the center as it is when working on the double bed.

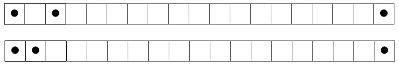

Introducing patterning single bed: knit weaving is perhaps the best way to control the number of plies, color mixing, designs in vertical bands, and knitting 2 fringe lengths at the same time. The 1/1 brother card is the most basic, but small repeats can be isolated for more interest or syncing with designs in garment pieces. To start: cast on and knit at least 2 rows on the chosen needle arrangement. Hang claw weights (or smaller) on each block of stitches. Combining strands for weaving adds fullness to the fringe. When any fringe is removed from the machine it should be stretched lengthwise and steamed to set the stitches (which I did not do in any of my swatches). As with other samples, the odd small number of stitches in the center or on the side are cut off to release the fringe. A sample arrangement: odd number of needles on either side and center, even number of needles out of work in-between.  Visualizing the punchcard or electronic needle selection on the same number of needles in work as above helps. Here the first and last needle on each side knits at the start. End needle selection is off; if it is not the outside automatic needle selection will give that edge a different look. Using both settings will help determine if one is more preferred than the other.

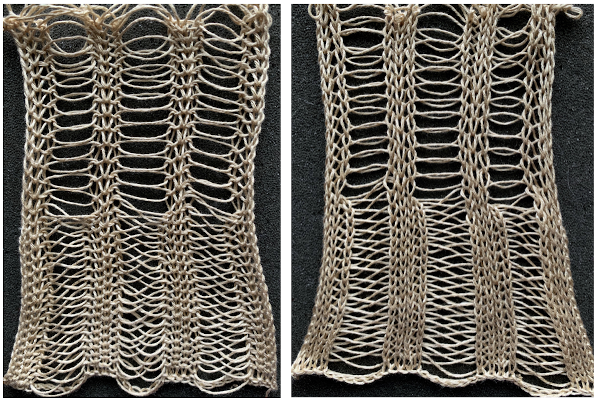

Visualizing the punchcard or electronic needle selection on the same number of needles in work as above helps. Here the first and last needle on each side knits at the start. End needle selection is off; if it is not the outside automatic needle selection will give that edge a different look. Using both settings will help determine if one is more preferred than the other.  A closer look at both sides of my ancient swatch knit in 2/8 wool

A closer look at both sides of my ancient swatch knit in 2/8 wool

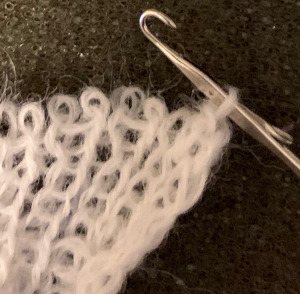

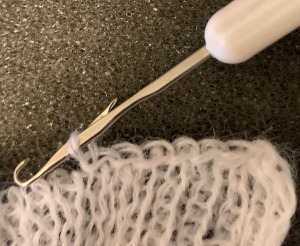

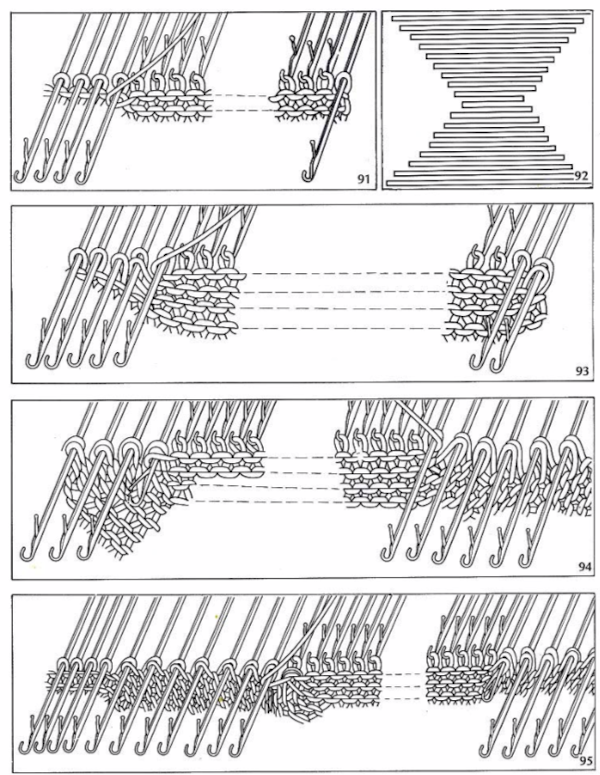

Long loops are best in a thicker yarn, here they are shown in an every other needle arrangement using mohair on 2/8 wool ground

Long loops are best in a thicker yarn, here they are shown in an every other needle arrangement using mohair on 2/8 wool ground related post reviews some of the methods for creating the loops, there is at least one other. Published directions have taken it for granted that thinner yarn is in use: if working on a machine with a ribber use the gate pegs on the ribber as your gauge. Wind the yarn around the needle, then down to the sinker plate below it with ribber down one position, then around the same needle, down to the same gate peg, then up and around the next needle, continuing across. When the row of loops is completed, knit several rows, and lift the ribber up to release loops.

related post reviews some of the methods for creating the loops, there is at least one other. Published directions have taken it for granted that thinner yarn is in use: if working on a machine with a ribber use the gate pegs on the ribber as your gauge. Wind the yarn around the needle, then down to the sinker plate below it with ribber down one position, then around the same needle, down to the same gate peg, then up and around the next needle, continuing across. When the row of loops is completed, knit several rows, and lift the ribber up to release loops.

My test is with yarns of 2 thicknesses, one half the number of plies in the other. Cast on with background yarn, knit at least 2 rows. I wrapped the 4-ply on every needle on the main bed counterclockwise when moving from left to right (think e wrapping in either direction), clockwise when moving from right to left, bringing it down and around the corresponding gate peg. I found it easier to work with needles that were to be wrapped and moved forward from the B position.  The loops prior to being lifted off sinker plates

The loops prior to being lifted off sinker plates  The first ribber height drop produced short loops (2.5 cm)

The first ribber height drop produced short loops (2.5 cm) With ribber in the down most position (4.5 cm loops)

With ribber in the down most position (4.5 cm loops)

I found that just by knitting 3 more rows in this yarn I could lift the loops off the ribber gate pegs easily, dropping them between the beds and repeating the process. No need to raise the ribber back up. Whether these loops will bear being cut or be too slippery to stay in the ground will be determined by yarn choices.

I found that just by knitting 3 more rows in this yarn I could lift the loops off the ribber gate pegs easily, dropping them between the beds and repeating the process. No need to raise the ribber back up. Whether these loops will bear being cut or be too slippery to stay in the ground will be determined by yarn choices.

There are times when a fringe is desired on one or both sides of the piece. Simply leaving needles out of work and an additional one in use to determine the width of the fringe can have skimpy results and an unstable edge stitch on the knit body. This is my solution for solving both: I began by knitting a couple of rows in the background yarn, then added a strand of yellow, and eventually the third strand in light blue, e wrapping the extra strand(s) in the direction away from the carriage.

In this case, knitting ended opposite the fringe, only these stitches were bound off, not the single one on the far right

In this case, knitting ended opposite the fringe, only these stitches were bound off, not the single one on the far right  The single stitch column was trimmed off, leaving a fairly full, stable fringe.

The single stitch column was trimmed off, leaving a fairly full, stable fringe.

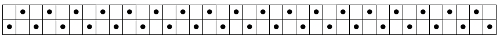

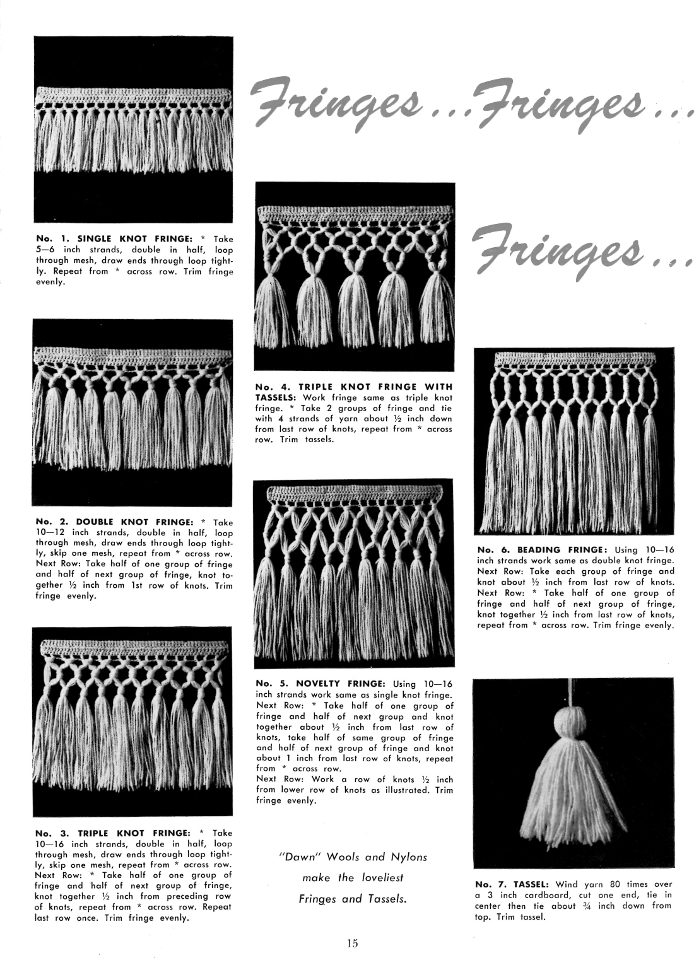

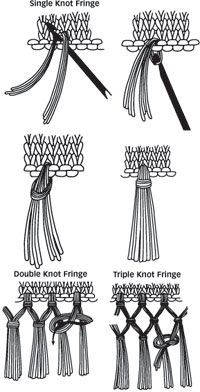

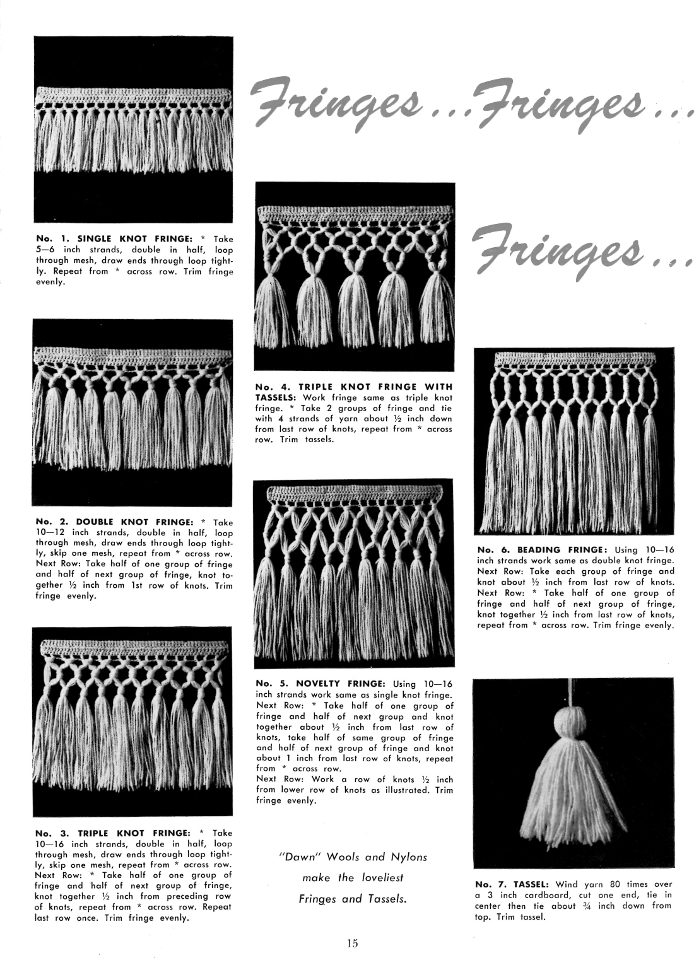

Cut lengths of yarn may be added to edge or in the body of the knit, eyelets could be used as markers or for an all-over fabric, guiding placement. This illustration is from Annie’s catalog

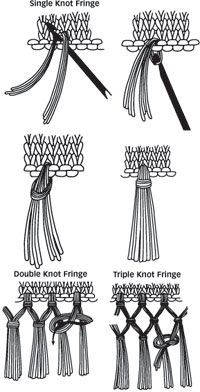

Cut lengths of yarn may be added to edge or in the body of the knit, eyelets could be used as markers or for an all-over fabric, guiding placement. This illustration is from Annie’s catalog  Fringes could also be crocheted or hand-knit, used to cast on the piece or be stitched in place upon its completion. I do not have the source for this, will credit it if I can find one

Fringes could also be crocheted or hand-knit, used to cast on the piece or be stitched in place upon its completion. I do not have the source for this, will credit it if I can find one

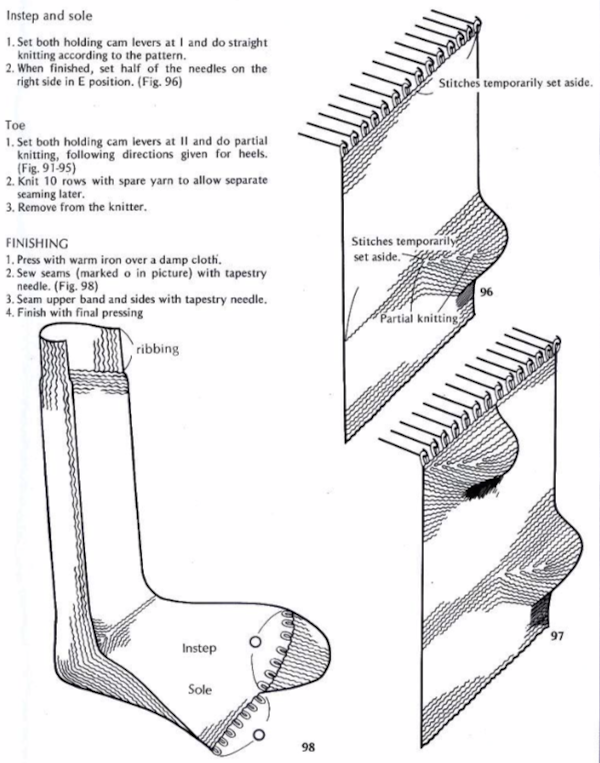

the knit side, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right

the knit side, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right  every other needle, purl side facing, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right, with markers indicating the “extra float”

every other needle, purl side facing, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right, with markers indicating the “extra float”  the knit side, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right

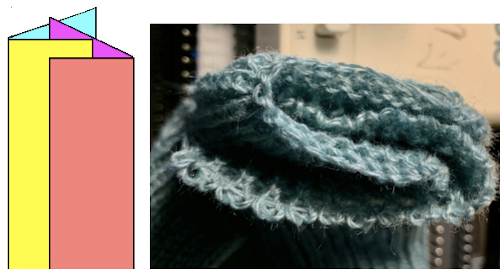

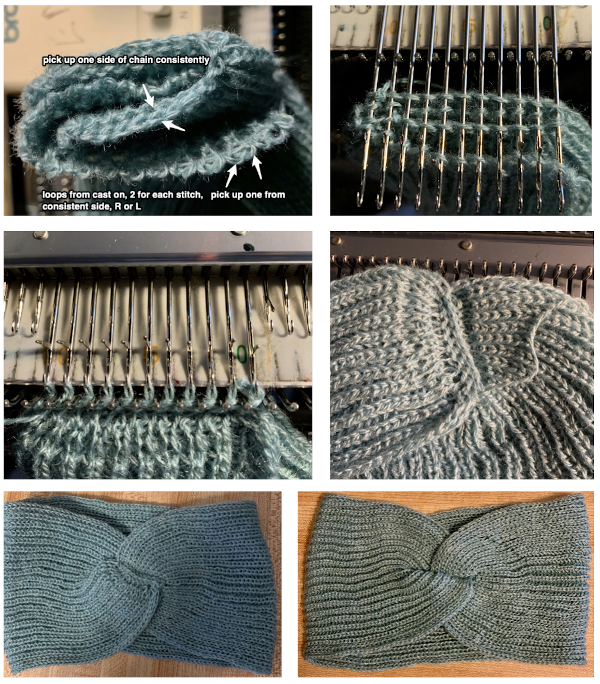

the knit side, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right  I knit the samples as tightly as possible. When making dbj slip stitch scarves I wanted the bottom to match the top in width. The ribber stitches were transferred to the main bed and tested on a test swatch whether I preferred to knit an added row or not before performing a latch tool bind off around gate pegs. To deal with the cast on width, I simply planned to knit the zig-zag row on at least garment tension, thus leaving me with what are normally considered ugly loops. There are 2 such loops for each stitch. With a latch tool, begin opposite the yarn end, and consistently choose the next right or left loop, chaining them through each other.

I knit the samples as tightly as possible. When making dbj slip stitch scarves I wanted the bottom to match the top in width. The ribber stitches were transferred to the main bed and tested on a test swatch whether I preferred to knit an added row or not before performing a latch tool bind off around gate pegs. To deal with the cast on width, I simply planned to knit the zig-zag row on at least garment tension, thus leaving me with what are normally considered ugly loops. There are 2 such loops for each stitch. With a latch tool, begin opposite the yarn end, and consistently choose the next right or left loop, chaining them through each other. proceeding toward the yarn end, pick up one of the next 2 loops in the hook, here I consistently chose the one on the right

proceeding toward the yarn end, pick up one of the next 2 loops in the hook, here I consistently chose the one on the right  if the first loop slips in the hook again as well, get it behind the latch once more before proceeding

if the first loop slips in the hook again as well, get it behind the latch once more before proceeding pull the second loop through the previous one

pull the second loop through the previous one  work across the row, secure the yarn end

work across the row, secure the yarn end  the appearance on the reverse side

the appearance on the reverse side  I can be a little bonkers with my finishing, have even been known when dealing with getting top and bottom edges to match in look and width to rehang every other loop, knit a row, and then perform the latch tool bind off. If tuck double bed fabrics are knit, they require planning for loose cast-ons and bind-offs. Slip stitch is short and thin, tuck stitch is short and fat, whether knit single or double bed and then is compared with fabrics where either bed predominantly knits plain.

I can be a little bonkers with my finishing, have even been known when dealing with getting top and bottom edges to match in look and width to rehang every other loop, knit a row, and then perform the latch tool bind off. If tuck double bed fabrics are knit, they require planning for loose cast-ons and bind-offs. Slip stitch is short and thin, tuck stitch is short and fat, whether knit single or double bed and then is compared with fabrics where either bed predominantly knits plain.

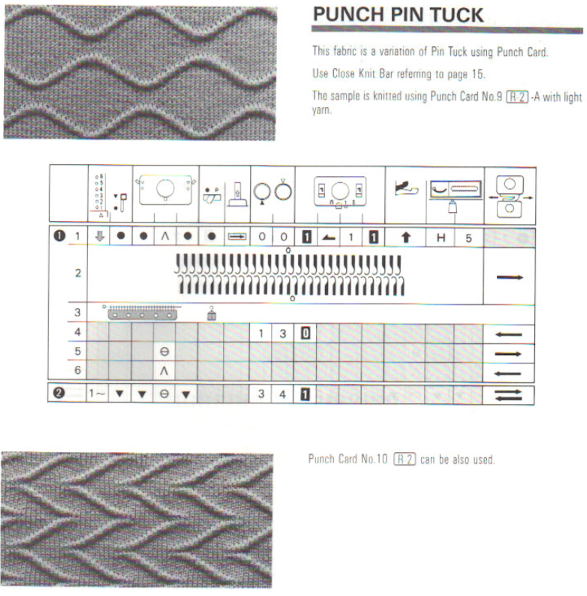

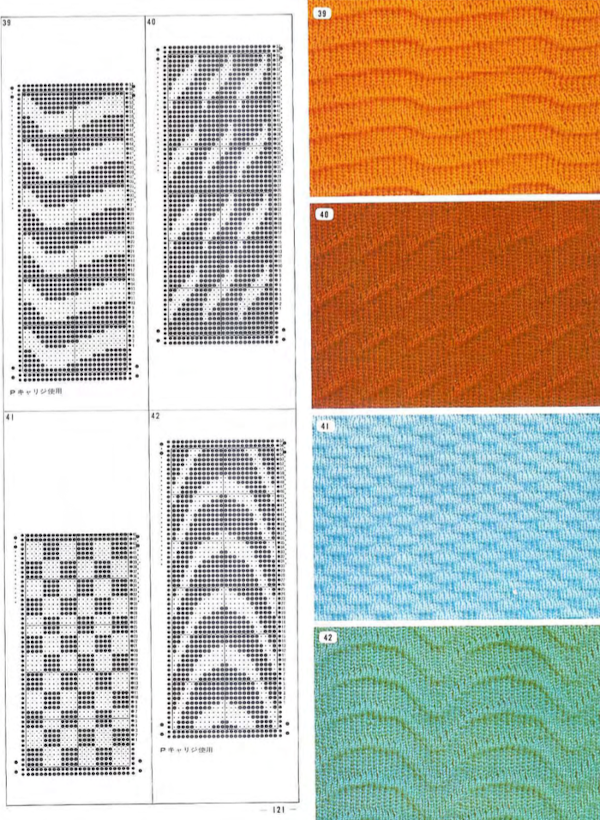

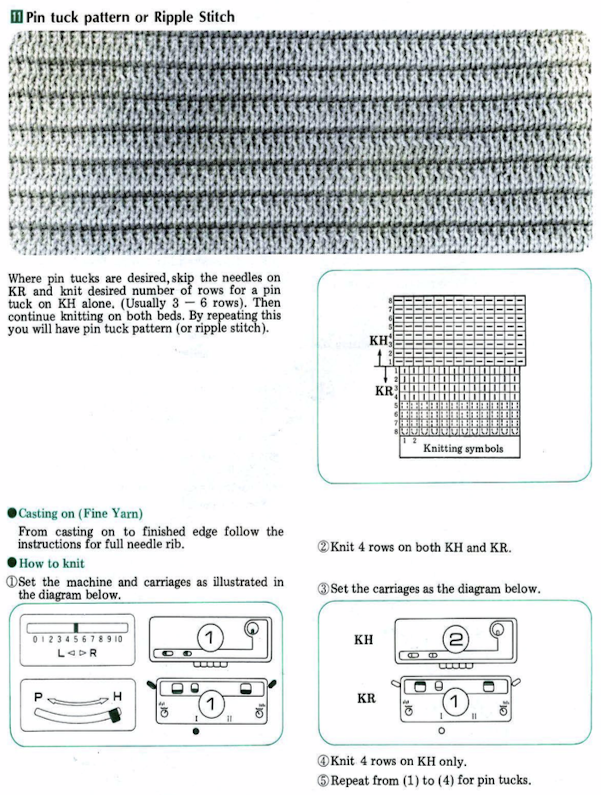

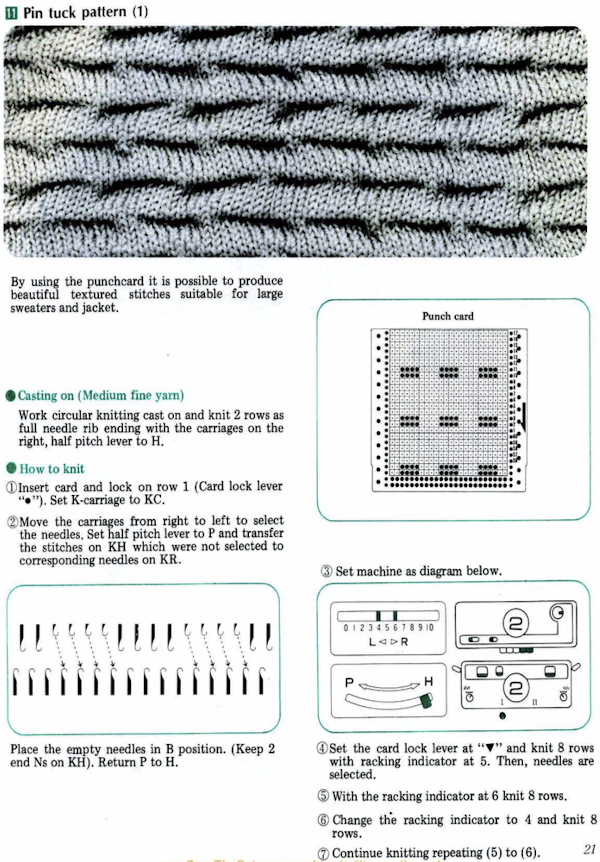

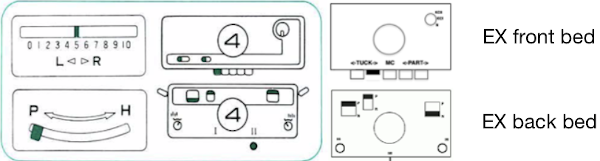

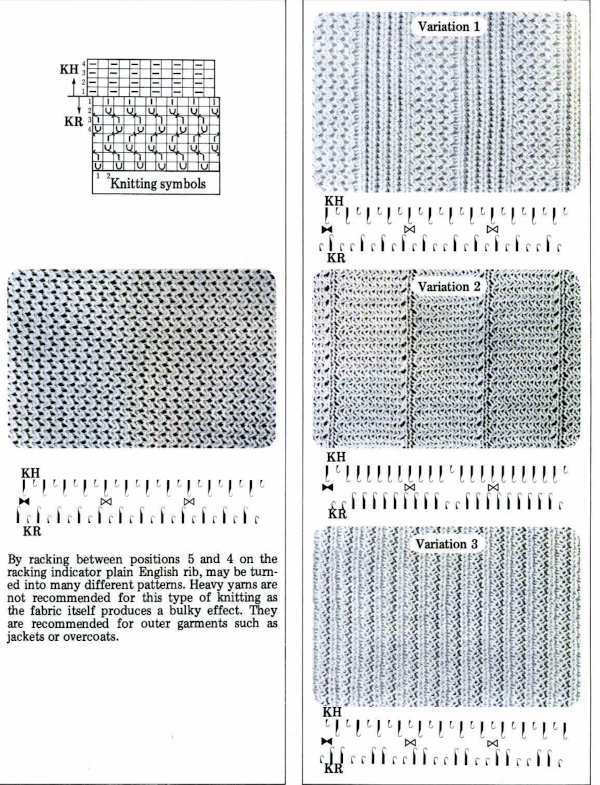

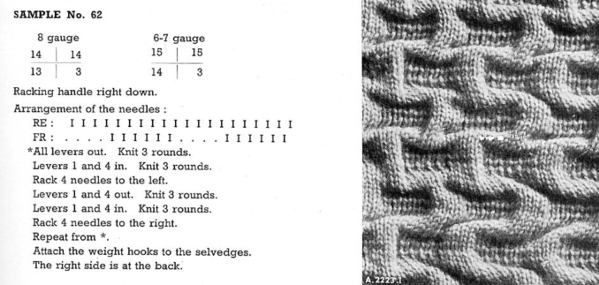

from the Brother Ribber techniques book

from the Brother Ribber techniques book

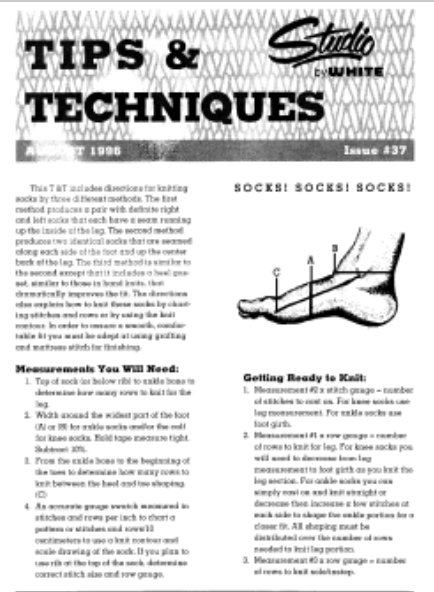

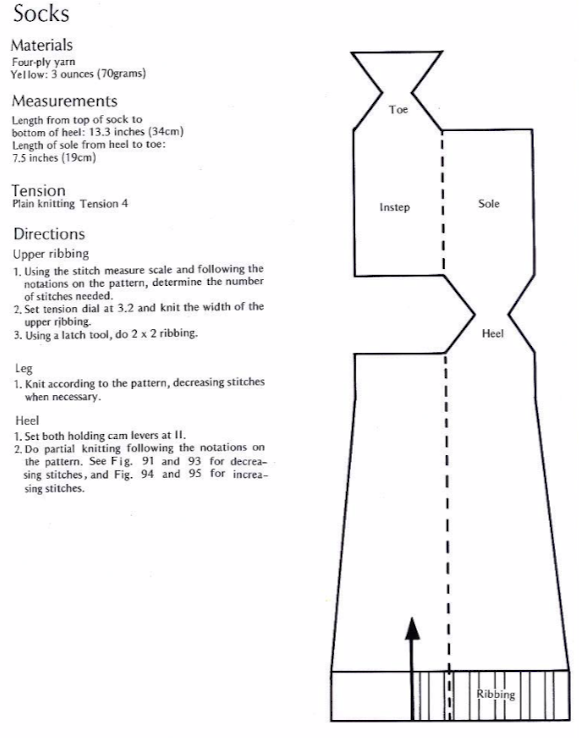

Patterns from manufacturers: Superba manual

Patterns from manufacturers: Superba manual

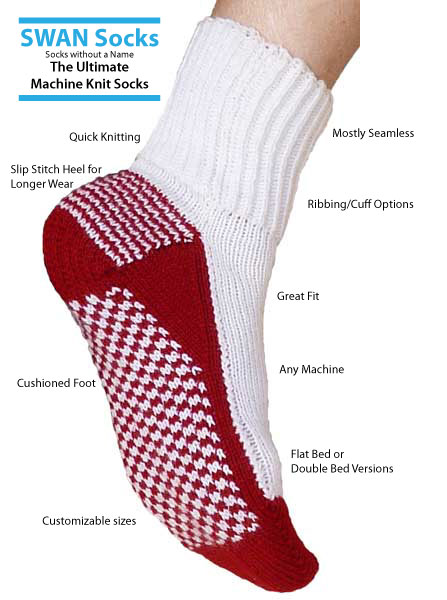

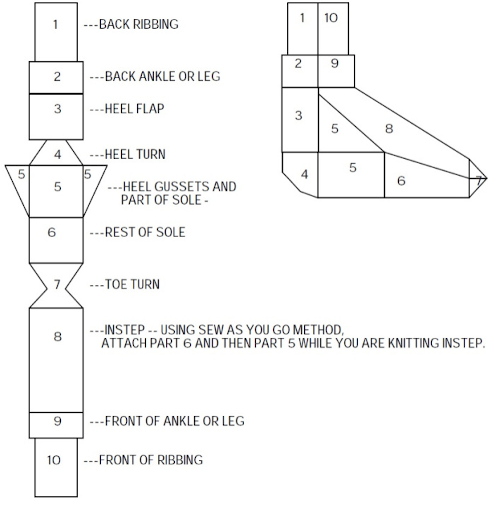

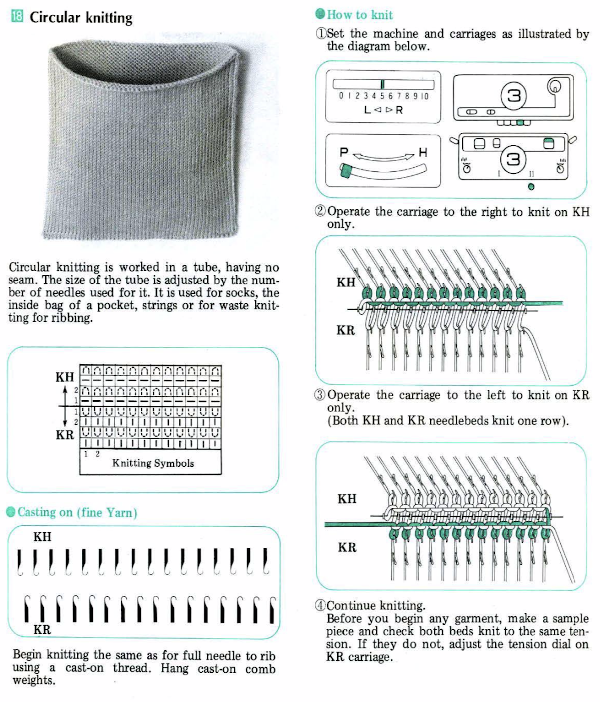

on page 38 a repeat and instructions are offered for a spiral tube sock. The latter has no heel shaping, but traditional toe shaping can be added.

on page 38 a repeat and instructions are offered for a spiral tube sock. The latter has no heel shaping, but traditional toe shaping can be added.

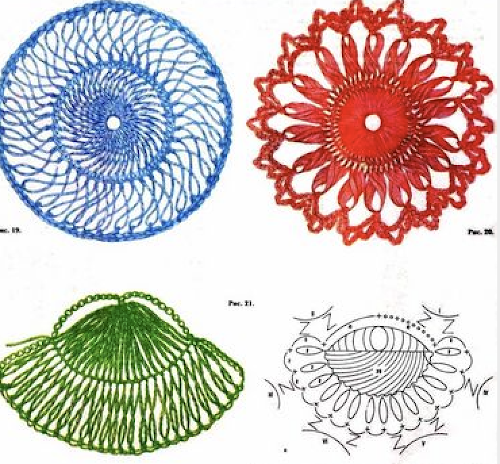

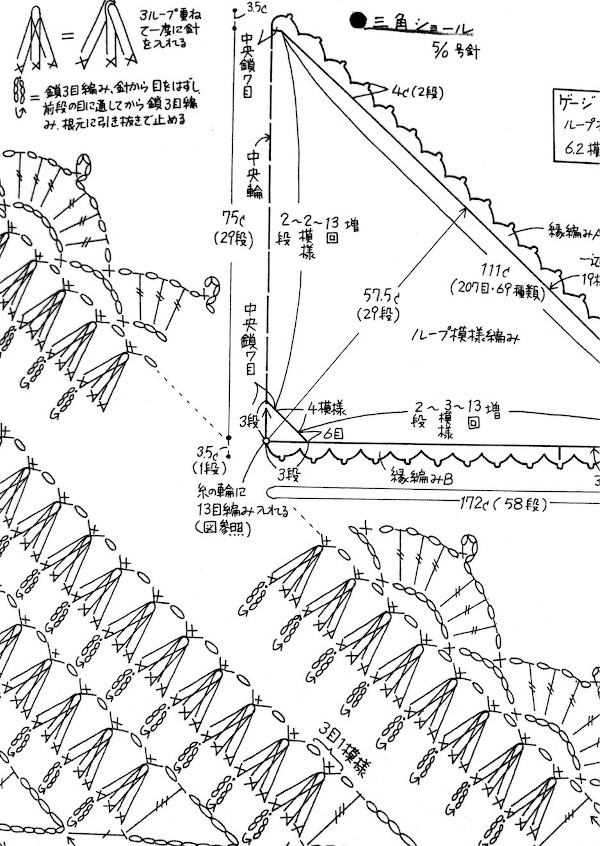

Lastly, it is possible to knit socks sideways (as well as gloves), usually in garter stitch and in hand knitting. This is a crochet illustration that points to the general construction method.

Lastly, it is possible to knit socks sideways (as well as gloves), usually in garter stitch and in hand knitting. This is a crochet illustration that points to the general construction method.

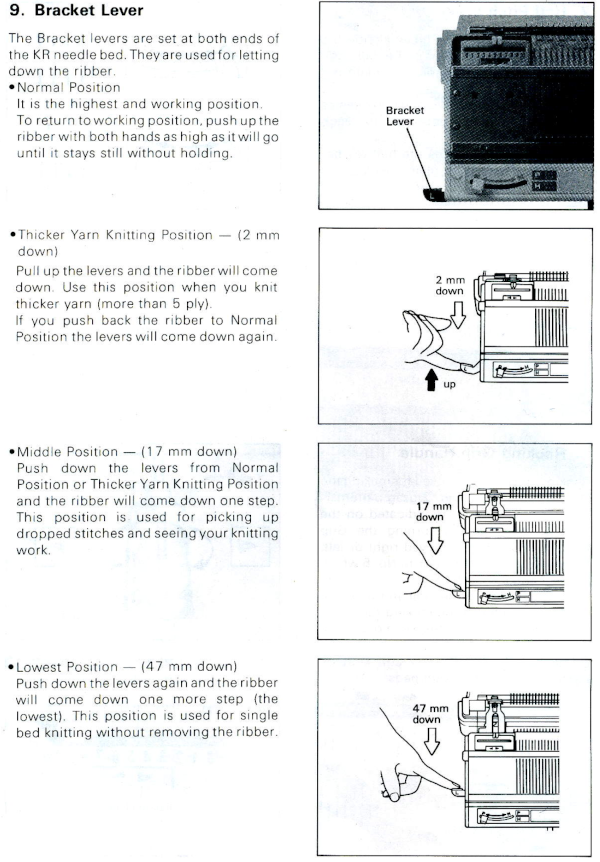

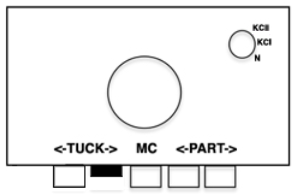

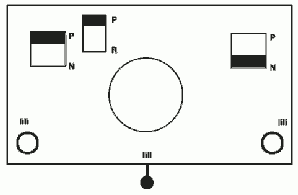

The elongated stitches at the top of the “band” are due to an extra needle in use on the ribber. To review, the proper settings from the Ribber Techniques Book:

The elongated stitches at the top of the “band” are due to an extra needle in use on the ribber. To review, the proper settings from the Ribber Techniques Book:

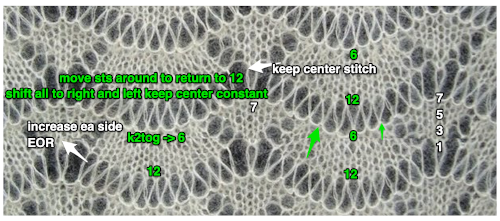

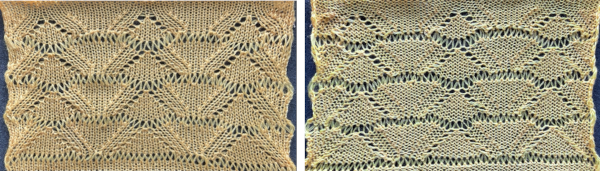

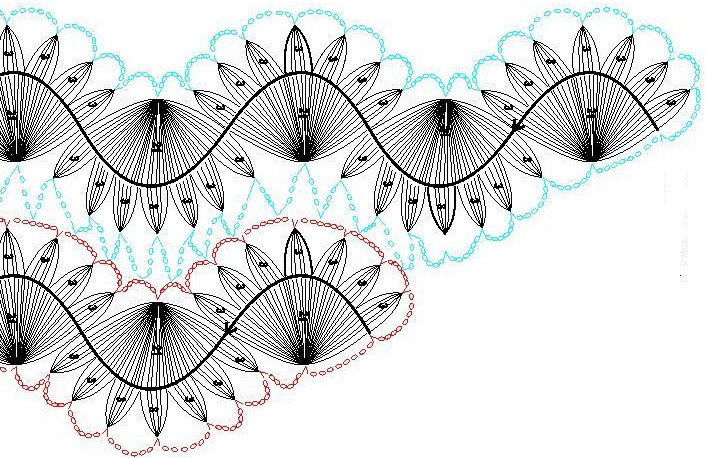

At about that time I came across this image on Pinterest.

At about that time I came across this image on Pinterest. It combines transfer lace and long stitches, has characteristics that make some lace patterns unable to be reproduced on home knitting machines. Upon inspection, one will see that the number of stitches varies in different parts of the repeat. Aside from creating eyelets, the smaller triangular shapes increase in width, the fan shapes are decreased by half on their top row. Long stitches are created across all needles in work, then they are reconfigured so the center single stitch of the triangle and the center 2 stitches of the fan shape realign in the same position. The number of stitches at the start of the pattern and after the long stitches are created remains constant.

It combines transfer lace and long stitches, has characteristics that make some lace patterns unable to be reproduced on home knitting machines. Upon inspection, one will see that the number of stitches varies in different parts of the repeat. Aside from creating eyelets, the smaller triangular shapes increase in width, the fan shapes are decreased by half on their top row. Long stitches are created across all needles in work, then they are reconfigured so the center single stitch of the triangle and the center 2 stitches of the fan shape realign in the same position. The number of stitches at the start of the pattern and after the long stitches are created remains constant.  Trying variations on inspiration sources can lead to success, failure, somewhere in between, but also increase learning and skill that will carry over into other knitting techniques, even if the results are never used for a finished piece.

Trying variations on inspiration sources can lead to success, failure, somewhere in between, but also increase learning and skill that will carry over into other knitting techniques, even if the results are never used for a finished piece.

I found making the transfers easier an the process more visible if I dropped one side of the ribber to the second, 17 mm. position

I found making the transfers easier an the process more visible if I dropped one side of the ribber to the second, 17 mm. position

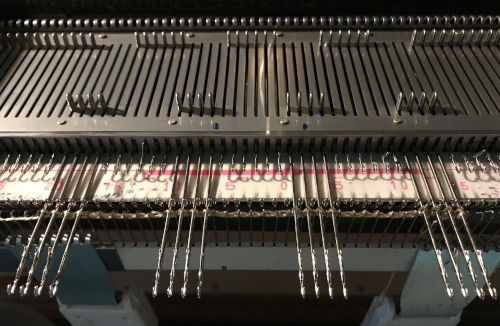

The ribber is set to N <– –> for three rows. On the first pass, all its needles will pick up the yarn, creating loops on every needle

The ribber is set to N <– –> for three rows. On the first pass, all its needles will pick up the yarn, creating loops on every needle

With the ribber carriage alone, still set to N/N, free it, and make two passes to and from its starting side. The first pass releases the loops, the second returns it for coupling with the knit carriage. Below the long loops can be seen. My needle tape is “somewhere”, has not yet been returned to the ribber after my racking handle adventures were completed.

With the ribber carriage alone, still set to N/N, free it, and make two passes to and from its starting side. The first pass releases the loops, the second returns it for coupling with the knit carriage. Below the long loops can be seen. My needle tape is “somewhere”, has not yet been returned to the ribber after my racking handle adventures were completed.  Return the ribber settings to slip in both directions, and repeat the process. Dropping the ribber to the lowest position at any point can verify goings-onHere one row has been knit on the main bed only, anchoring the loops, returning carriages to the opposite side prior to starting transfers once more

Return the ribber settings to slip in both directions, and repeat the process. Dropping the ribber to the lowest position at any point can verify goings-onHere one row has been knit on the main bed only, anchoring the loops, returning carriages to the opposite side prior to starting transfers once more A word of caution: if loops are picked up on any single row that in theory was set to slip and was to be worked on only single bed, check to make certain the tuck lever has not been accidentally brought up to the tuck position. Although tuck <– –> can serve for a free pass on the main bed, having this setting on the ribber will create loops on all needles in work

A word of caution: if loops are picked up on any single row that in theory was set to slip and was to be worked on only single bed, check to make certain the tuck lever has not been accidentally brought up to the tuck position. Although tuck <– –> can serve for a free pass on the main bed, having this setting on the ribber will create loops on all needles in work

I cast on 55 stitches 27 left, 28 right. A ribber comb and weights are required.

I cast on 55 stitches 27 left, 28 right. A ribber comb and weights are required.

The zig-zag will lean slightly to one side

The zig-zag will lean slightly to one side

If that is understood then one can make the choice of moving left or right and be off and running in the pattern, aside from the starting side or some of the other directions given in patterns or manuals. Cam buttons and patterning may be introduced as well. This is how a row of knitting might appear after racking.

If that is understood then one can make the choice of moving left or right and be off and running in the pattern, aside from the starting side or some of the other directions given in patterns or manuals. Cam buttons and patterning may be introduced as well. This is how a row of knitting might appear after racking.

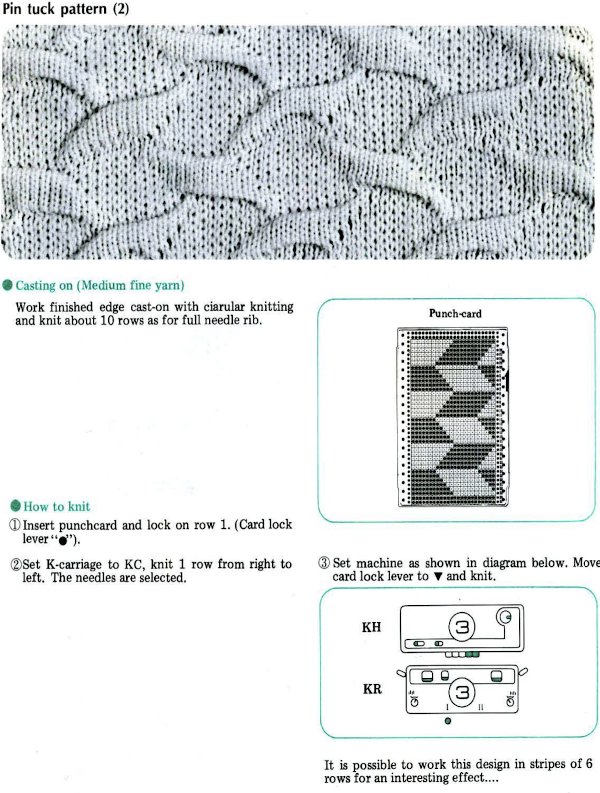

This page from the Ribber Techniques book shows fabrics knit on EON, adding tuck cam buttons into the mix and slightly different needle arrangements, varying the look of the finished knitting.

This page from the Ribber Techniques book shows fabrics knit on EON, adding tuck cam buttons into the mix and slightly different needle arrangements, varying the look of the finished knitting.

If multiple side-by-side stitches are in work on the ribber, the half-pitch setting applies as well. When tucking is added, for increased stretch, it may be necessary to compensate for the width of the resulting fabric by casting-on on every needle and then transferring in the desired configuration between the beds. Transferring is easier done in full pitch with a return to half-pitch prior to continuing to knit. The bind-off is likely to require considerations for an added stretch as well. Slip stitch narrows the fabric. Such adjustments are usually worked out in test swatches.

If multiple side-by-side stitches are in work on the ribber, the half-pitch setting applies as well. When tucking is added, for increased stretch, it may be necessary to compensate for the width of the resulting fabric by casting-on on every needle and then transferring in the desired configuration between the beds. Transferring is easier done in full pitch with a return to half-pitch prior to continuing to knit. The bind-off is likely to require considerations for an added stretch as well. Slip stitch narrows the fabric. Such adjustments are usually worked out in test swatches.

By the way, the racking position indicators are slightly different in the Brother standard vs. the Brother bulky machines

By the way, the racking position indicators are slightly different in the Brother standard vs. the Brother bulky machines

e wrapping with second yarn before moving to left

e wrapping with second yarn before moving to left  e wrapping with second yarn prior to returning to right, completing a sideways figure 8, end stitches out to E before prior to each carriage pass

e wrapping with second yarn prior to returning to right, completing a sideways figure 8, end stitches out to E before prior to each carriage pass  When the required number of rows has been knit, end COR. Unravel the first stitch on the right,

When the required number of rows has been knit, end COR. Unravel the first stitch on the right,

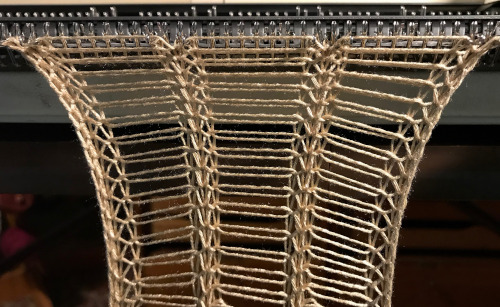

Using thinner yarn for knitting after the join even if on the same number of stitches, will gather the fabric

Using thinner yarn for knitting after the join even if on the same number of stitches, will gather the fabric

More on seaming and joining knits

More on seaming and joining knits  strips of different colors used

strips of different colors used

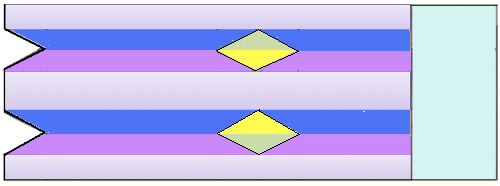

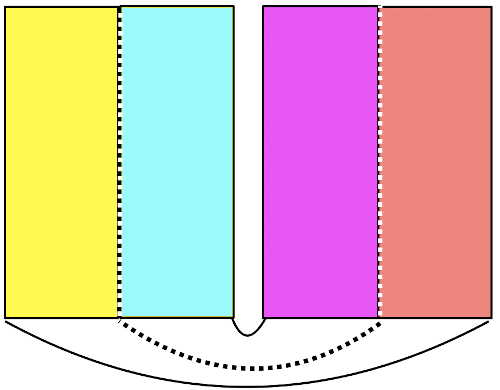

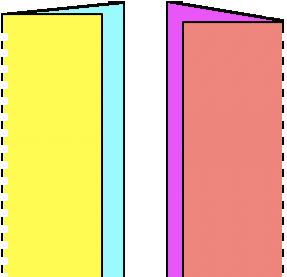

The convention for joining strips of machine knitting by crocheting or latching side loops together suggest having a ladder space (white square, one or more may be used) and a side edge stitch on either side in segments of the final piece ie. afghan strips.

The convention for joining strips of machine knitting by crocheting or latching side loops together suggest having a ladder space (white square, one or more may be used) and a side edge stitch on either side in segments of the final piece ie. afghan strips.

A partial illustration from Pinterest from an unknown source showing how the loops coming together to make shapes might be charted out: the ovals represent chain stitches, the v slip stitches, the different colors the finish of a complete strip’s edge

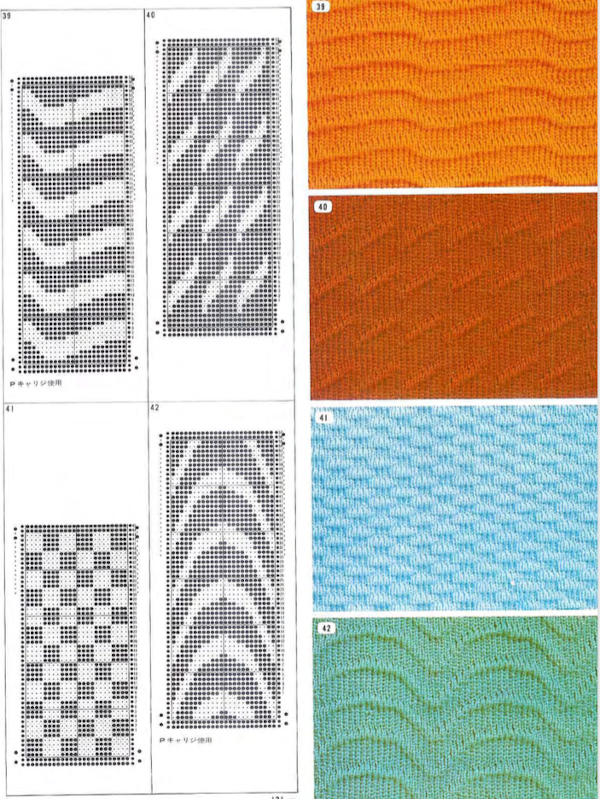

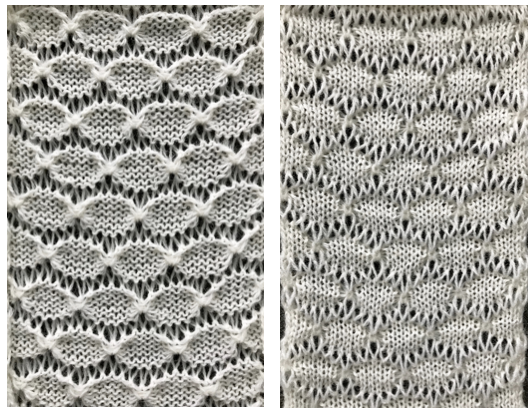

A partial illustration from Pinterest from an unknown source showing how the loops coming together to make shapes might be charted out: the ovals represent chain stitches, the v slip stitches, the different colors the finish of a complete strip’s edge  Tuck lace is a fabric produced with needles out of work in combination with tuck patterning on the main bed. Patterns for it can serve as the starting point for either the center strips in double-sided loop fabrics or they can be worked in repeats with wider ladder spaces between them for a far quicker “pretend” version. This is one of my ancient swatches for the technique from a classroom demo, using the 1X1 punchcard, shown sideways to save space.

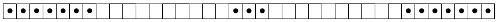

Tuck lace is a fabric produced with needles out of work in combination with tuck patterning on the main bed. Patterns for it can serve as the starting point for either the center strips in double-sided loop fabrics or they can be worked in repeats with wider ladder spaces between them for a far quicker “pretend” version. This is one of my ancient swatches for the technique from a classroom demo, using the 1X1 punchcard, shown sideways to save space. The card is used at normal rotation. Any time there are needles out of work, end needle selection is canceled to maintain patterning throughout including on end needles of each vertical strip. Tuck <– –> is used resulting in texture as opposed to simple stocking stitch and ladder fabric (center of the swatch). In the right segment, the ladder threads are twisted, in the one on the left they are not. This is what is happening: for twisted ladders on an even total number of needles have an even number in the selected pattern (4), and an even number out of work (6). This is one fabric that definitely benefits from the use of some evenly distributed weight and a good condition sponge bar. End needle selection must be canceled

The card is used at normal rotation. Any time there are needles out of work, end needle selection is canceled to maintain patterning throughout including on end needles of each vertical strip. Tuck <– –> is used resulting in texture as opposed to simple stocking stitch and ladder fabric (center of the swatch). In the right segment, the ladder threads are twisted, in the one on the left they are not. This is what is happening: for twisted ladders on an even total number of needles have an even number in the selected pattern (4), and an even number out of work (6). This is one fabric that definitely benefits from the use of some evenly distributed weight and a good condition sponge bar. End needle selection must be canceled

Here the stitches are arranged with an odd number in work (3), an odd number out of work (7)

Here the stitches are arranged with an odd number in work (3), an odd number out of work (7)

I made a few items with twisted strands inspired by those seen in wovens produced by my weaving friends. I have no photos of those, failed to document my work for quite a few years. One excuse was the quality of any photos I attempted, and even back in the day, professional photographers charged $180 an hour plus model fees if used. It seemed that adding the cost of such photography to limited edition runs that were planned for sale would make the wholesale price higher than the market would bear. We all make choices based on information we have at that particular time, which was long before the recent easy-to-use photo technology.

I made a few items with twisted strands inspired by those seen in wovens produced by my weaving friends. I have no photos of those, failed to document my work for quite a few years. One excuse was the quality of any photos I attempted, and even back in the day, professional photographers charged $180 an hour plus model fees if used. It seemed that adding the cost of such photography to limited edition runs that were planned for sale would make the wholesale price higher than the market would bear. We all make choices based on information we have at that particular time, which was long before the recent easy-to-use photo technology. Here a ladder space created by needles out of work is left between vertical fair isle repeats, producing a fringe in 2 colors. The design was not planned, a standard punchcard was used for the purpose of the demo. A planned repeat would have more impact. End needle selection is on, which is usual in FI, not for most patterns with either tuck or slip stitch settings combined with needles out of work, is also true here so that a vertical line on each side of the needles out of work between repeats aids in sewing the strips together. Width is limited since the fabric will be gathered by seaming and become significantly narrower and likely turned sideways. Both sides are shown. Joining could be planned to occur only at the bottom of a piece if desired, stitching lines will be less visible if thread color matches that of the yarn

Here a ladder space created by needles out of work is left between vertical fair isle repeats, producing a fringe in 2 colors. The design was not planned, a standard punchcard was used for the purpose of the demo. A planned repeat would have more impact. End needle selection is on, which is usual in FI, not for most patterns with either tuck or slip stitch settings combined with needles out of work, is also true here so that a vertical line on each side of the needles out of work between repeats aids in sewing the strips together. Width is limited since the fabric will be gathered by seaming and become significantly narrower and likely turned sideways. Both sides are shown. Joining could be planned to occur only at the bottom of a piece if desired, stitching lines will be less visible if thread color matches that of the yarn

A needle in work away from the edge produces a side “fringe” followed here by felting partially, cutting the single edge stitch, and finishing the felting process

A needle in work away from the edge produces a side “fringe” followed here by felting partially, cutting the single edge stitch, and finishing the felting process Adding thicker or multiple strands of yarns in

Adding thicker or multiple strands of yarns in

Most often every other needle use is best. Here lace and pom trims are used, purchased fringes of all sorts could be applied the same way anywhere in the piece, joins to knit can be seen.

Most often every other needle use is best. Here lace and pom trims are used, purchased fringes of all sorts could be applied the same way anywhere in the piece, joins to knit can be seen.  A length of roving may be twisted in its center and applied as you knit. For a while mittens using it as a lining for warmth were popular. A video by Carole Wurst shows a method used in socks

A length of roving may be twisted in its center and applied as you knit. For a while mittens using it as a lining for warmth were popular. A video by Carole Wurst shows a method used in socks

The thickness of the yarn chosen is of critical importance. When I first attempted to knit a version of it on my 930 I encountered problems. To start with, I kept dropping off the stitches on one side or the other. I checked the ribber alignment, proper placement of the cast on comb, switched ribbers, and carriages, and continued to have problems. After all that, the solution turned out to be simply adding another 4 stitches (2 on each bed) toward the center of the piece (I did not count). Here I used a 2/24 which obviously does not have enough body to use as an edging. The Brother equivalent for the Duo setting is half fisherman rib, where one carriage knits in one direction, tucks in the other on every needle for every 2 rows knit, while the other bed’s carriage does the same, but in opposite directions. I used 3 needles on each side rather than 2 as in the Duo repeat, starting with the first needle in work on the left on the ribber, the last needle in work on the right on the top bed. One may begin to knit on either side, but when manually setting the cam buttons lead with settings so that first stitch knits as it moves to the opposite side. Using waste yarn at the start of the piece will produce a better cast on edge for the trim. Operating from the right:

The thickness of the yarn chosen is of critical importance. When I first attempted to knit a version of it on my 930 I encountered problems. To start with, I kept dropping off the stitches on one side or the other. I checked the ribber alignment, proper placement of the cast on comb, switched ribbers, and carriages, and continued to have problems. After all that, the solution turned out to be simply adding another 4 stitches (2 on each bed) toward the center of the piece (I did not count). Here I used a 2/24 which obviously does not have enough body to use as an edging. The Brother equivalent for the Duo setting is half fisherman rib, where one carriage knits in one direction, tucks in the other on every needle for every 2 rows knit, while the other bed’s carriage does the same, but in opposite directions. I used 3 needles on each side rather than 2 as in the Duo repeat, starting with the first needle in work on the left on the ribber, the last needle in work on the right on the top bed. One may begin to knit on either side, but when manually setting the cam buttons lead with settings so that first stitch knits as it moves to the opposite side. Using waste yarn at the start of the piece will produce a better cast on edge for the trim. Operating from the right:

A 2/11.5 acrylic provided more of a tension adjustment challenge but made for a better fringe.

A 2/11.5 acrylic provided more of a tension adjustment challenge but made for a better fringe. The first and last 3 stitches on either side were transferred to the top bed and bound off, the center stitches were not, allowing them to be unraveled if desired ie in case the fringe is to be folded in half. Those extra center stitches also provide a guide for cutting either down their center (bottom of photo) or on either side of them (toward the top). I found the latter method to produce a cleaner cut line

The first and last 3 stitches on either side were transferred to the top bed and bound off, the center stitches were not, allowing them to be unraveled if desired ie in case the fringe is to be folded in half. Those extra center stitches also provide a guide for cutting either down their center (bottom of photo) or on either side of them (toward the top). I found the latter method to produce a cleaner cut line Suggestions for going wider with racked half fisherman rib on Japanese machines: begin with needle arrangement below, out of work needles can be as many as needed, set up and cast on with preferred racking position ie on 5, knit several rows in waste yarn making any adjustments needed so stitches knit are formed properly, weigh appropriately.

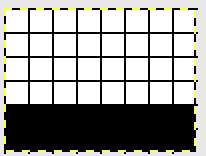

Suggestions for going wider with racked half fisherman rib on Japanese machines: begin with needle arrangement below, out of work needles can be as many as needed, set up and cast on with preferred racking position ie on 5, knit several rows in waste yarn making any adjustments needed so stitches knit are formed properly, weigh appropriately.  the edge that holds the fringe together is to be very narrow (or even added as one continues to knit) and one wishes to work on the single bed there are several options. With 4-ply and a “matching color” 2 ply I began with the top needle arrangement, and then switched to the one below it, knitting on a 4.5 mm machine.

the edge that holds the fringe together is to be very narrow (or even added as one continues to knit) and one wishes to work on the single bed there are several options. With 4-ply and a “matching color” 2 ply I began with the top needle arrangement, and then switched to the one below it, knitting on a 4.5 mm machine.  A permanent cast-on needs to take place in the preferred method over needles in work knit 2 rows. The stitch on the second needle from the left is going to want to stretch and tends not to be stable. To reduce that happening, there are 2 options involving the second strand of yarn. Here using a 2 ply helps serve that purpose and keeps the fringed strands closer together. The slower method is to remove the second stitch from the left on a tool after every 2 rows knit, then bring the separate yarn strand behind the now empty needle first from the right, then in turn from the left, returning the removed stitch to the machine, knitting 2 rows. I found that too slow for my patience, switched to just laying the second strand over needles before knitting each pair of rows, and decided to eliminate the out of work needle on the left side, moving the second stitch in work to its left.

A permanent cast-on needs to take place in the preferred method over needles in work knit 2 rows. The stitch on the second needle from the left is going to want to stretch and tends not to be stable. To reduce that happening, there are 2 options involving the second strand of yarn. Here using a 2 ply helps serve that purpose and keeps the fringed strands closer together. The slower method is to remove the second stitch from the left on a tool after every 2 rows knit, then bring the separate yarn strand behind the now empty needle first from the right, then in turn from the left, returning the removed stitch to the machine, knitting 2 rows. I found that too slow for my patience, switched to just laying the second strand over needles before knitting each pair of rows, and decided to eliminate the out of work needle on the left side, moving the second stitch in work to its left.  The single stitch on the far right of the chart need not be bound off. There will be 2 options after the work is off the machine. One is to unravel the single stitch column on the far right if loops are the goal, or cut it off, leaving a fairly good trimmed edge here, and what, in this yarn, appeared to me to be an acceptable edging. The 2 edge stitches on the left in my swatch did roll, making a very tight edge. Adjusting the tension used to change that effect would be another choice. Yarn use and personal taste contribute to a range of “successful” results when using any of these techniques.

The single stitch on the far right of the chart need not be bound off. There will be 2 options after the work is off the machine. One is to unravel the single stitch column on the far right if loops are the goal, or cut it off, leaving a fairly good trimmed edge here, and what, in this yarn, appeared to me to be an acceptable edging. The 2 edge stitches on the left in my swatch did roll, making a very tight edge. Adjusting the tension used to change that effect would be another choice. Yarn use and personal taste contribute to a range of “successful” results when using any of these techniques.

At the top of the piece, I transferred and doubled up the stitches on left, bound them off, and the yarn end(s) can be woven back into the cord.

At the top of the piece, I transferred and doubled up the stitches on left, bound them off, and the yarn end(s) can be woven back into the cord.  The side with the transfers is the “public” one, the finished fringe is usually hand sewn on, but it may also be used to cast on or be applied to several places in the knit both close together or at various intervals. Tension changes may be observed viewing from left to right, as well as the difference in length of loops as opposed to after the cutaway edge. The third stitch in work on the right may make for a more stable cutting line if looser tensions are preferred. Because the sinker plate used on the single bed has brushes and wheels in use, the width of the fringe can be considerable, without having to be concerned about stabilizing the center as it is when working on the double bed.

The side with the transfers is the “public” one, the finished fringe is usually hand sewn on, but it may also be used to cast on or be applied to several places in the knit both close together or at various intervals. Tension changes may be observed viewing from left to right, as well as the difference in length of loops as opposed to after the cutaway edge. The third stitch in work on the right may make for a more stable cutting line if looser tensions are preferred. Because the sinker plate used on the single bed has brushes and wheels in use, the width of the fringe can be considerable, without having to be concerned about stabilizing the center as it is when working on the double bed.

Long loops are best in a thicker yarn, here they are shown in an every other needle arrangement using mohair on 2/8 wool ground

Long loops are best in a thicker yarn, here they are shown in an every other needle arrangement using mohair on 2/8 wool ground

With ribber in the down most position (4.5 cm loops)

With ribber in the down most position (4.5 cm loops)

In this case, knitting ended opposite the fringe, only these stitches were bound off, not the single one on the far right

In this case, knitting ended opposite the fringe, only these stitches were bound off, not the single one on the far right

Cut lengths of yarn may be added to edge or in the body of the knit, eyelets could be used as markers or for an all-over fabric, guiding placement. This illustration is from

Cut lengths of yarn may be added to edge or in the body of the knit, eyelets could be used as markers or for an all-over fabric, guiding placement. This illustration is from  Fringes could also be crocheted or hand-knit, used to cast on the piece or be stitched in place upon its completion. I do not have the source for this, will credit it if I can find one

Fringes could also be crocheted or hand-knit, used to cast on the piece or be stitched in place upon its completion. I do not have the source for this, will credit it if I can find one

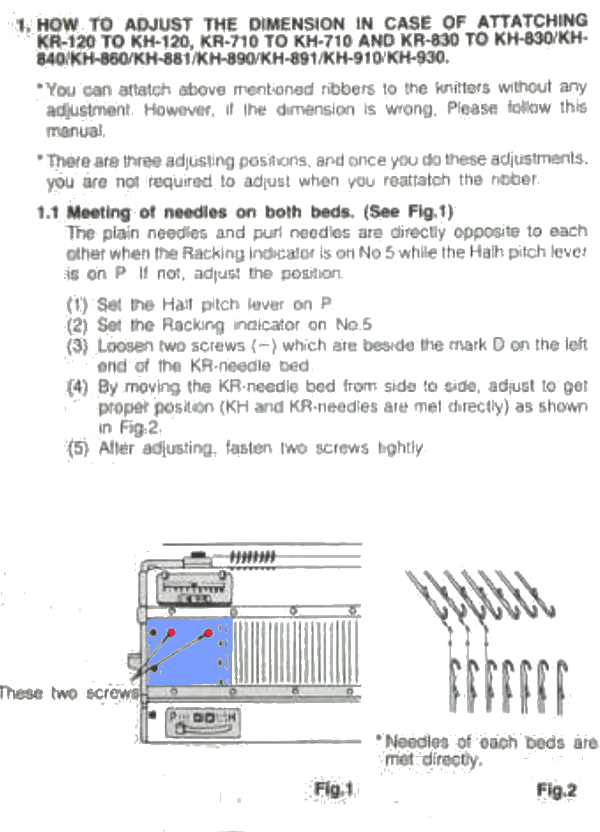

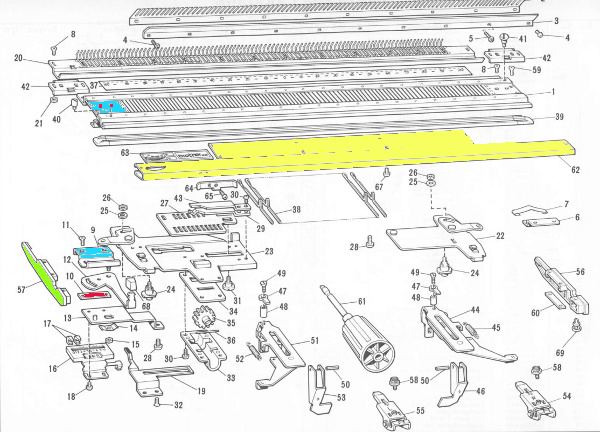

I asked on Ravelry for advice or shared experiences. A possible culprit was suggested to me, and I was pointed toward the

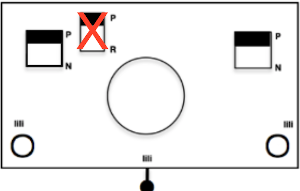

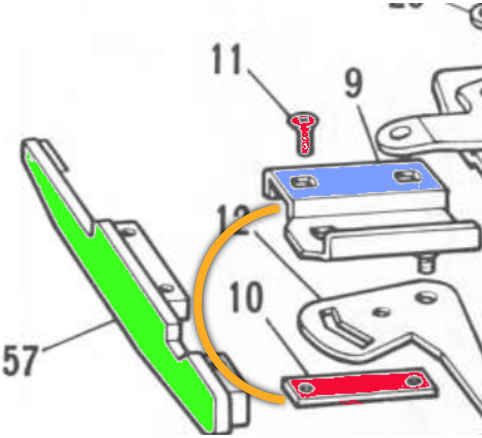

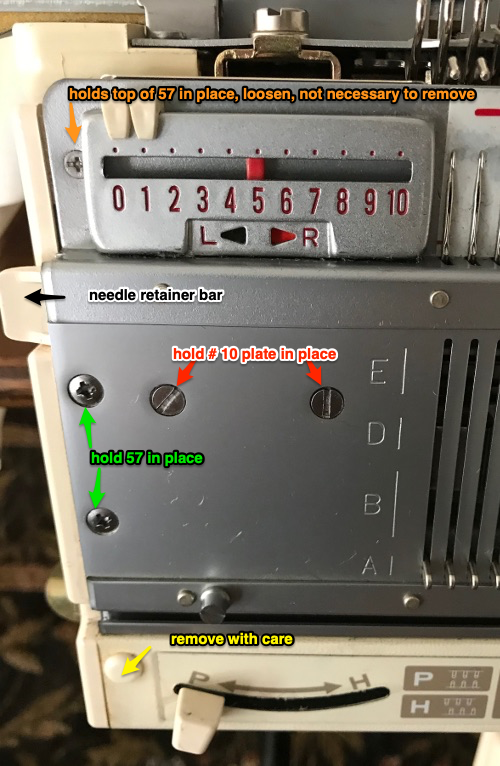

I asked on Ravelry for advice or shared experiences. A possible culprit was suggested to me, and I was pointed toward the When I tried to turn the screws marked in red I found they were loose. After I took apart the racking handle, braving far more disassembly than turned out to be needed, housing little screws and washers in separate small plastic containers along with their comrade larger parts, I found perhaps I could have reduced the effort considerably. I did not take photos during the process, as I was not brimming with confidence in the result. Enlarging a portion of the above helped me understand how parts related to each other a bit better.

When I tried to turn the screws marked in red I found they were loose. After I took apart the racking handle, braving far more disassembly than turned out to be needed, housing little screws and washers in separate small plastic containers along with their comrade larger parts, I found perhaps I could have reduced the effort considerably. I did not take photos during the process, as I was not brimming with confidence in the result. Enlarging a portion of the above helped me understand how parts related to each other a bit better.

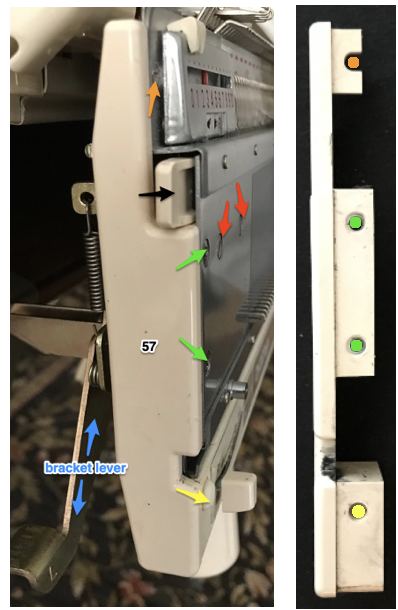

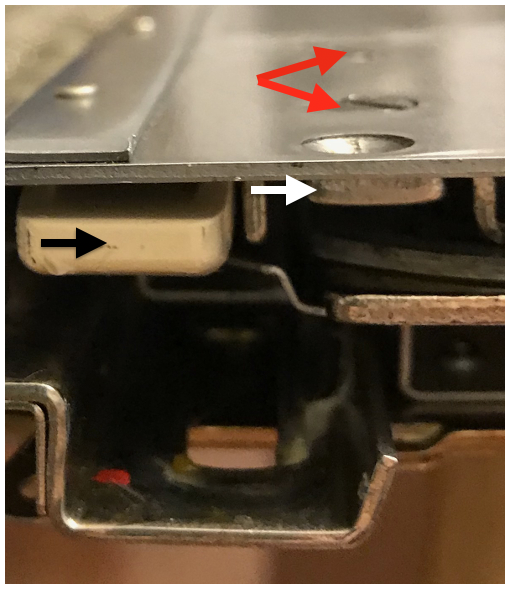

It really may not have been necessary to even remove the bracket lever. The #10 piece of metal was loose inside the machine, might simply have fallen out if I had turned the bed on its side and given it a mild shake after removing #57. This is with the piece in question in its housing where it belongs (white arrow), shown in relation to the needle retainer bar (black arrow) and screws marked with red arrows that hold it in place.

It really may not have been necessary to even remove the bracket lever. The #10 piece of metal was loose inside the machine, might simply have fallen out if I had turned the bed on its side and given it a mild shake after removing #57. This is with the piece in question in its housing where it belongs (white arrow), shown in relation to the needle retainer bar (black arrow) and screws marked with red arrows that hold it in place.  The piece is obviously thinner than the space it lives in, so for screws to anchor it properly, a flathead screwdriver or other improvised tool needs to be inserted under it, lifting it into position and holding it in place with its holes lined up with outside of bed so screws can grip it and be tightened properly.

The piece is obviously thinner than the space it lives in, so for screws to anchor it properly, a flathead screwdriver or other improvised tool needs to be inserted under it, lifting it into position and holding it in place with its holes lined up with outside of bed so screws can grip it and be tightened properly.

shown below on the right

shown below on the right

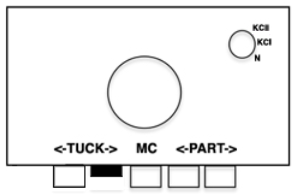

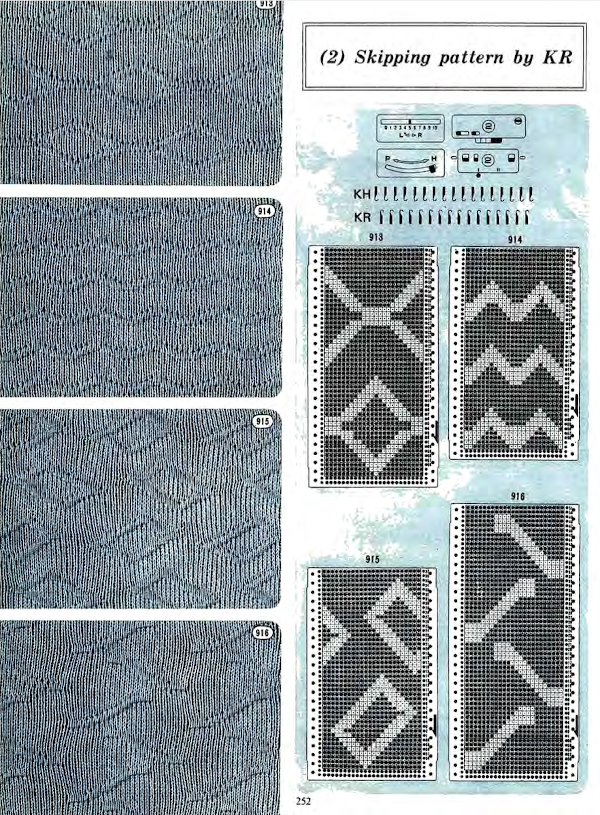

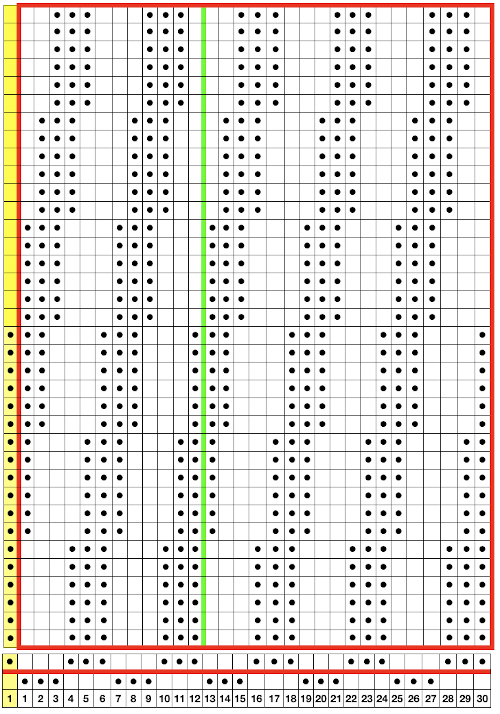

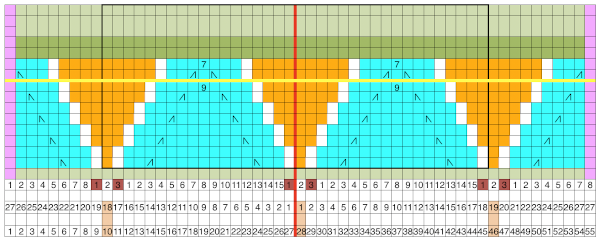

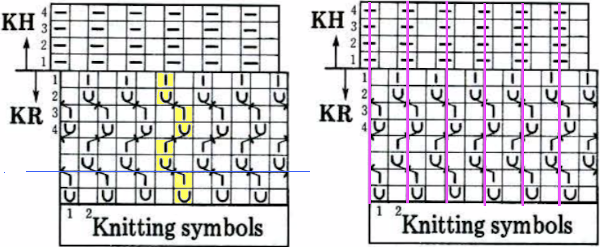

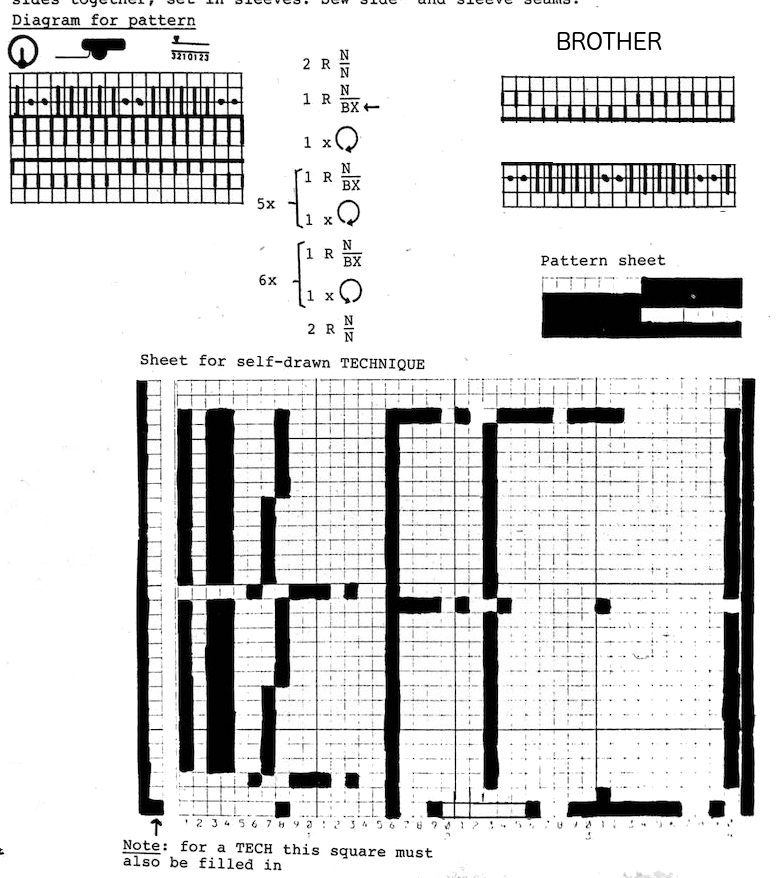

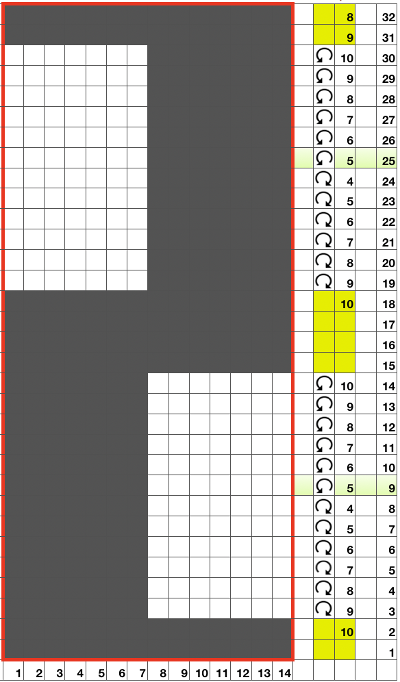

Translating Duo directions to black and white squares in order to develop a repeat for use on Brother: N/N is easy. The Duo is using buttons on the front bed and selection in response to their arrow setting to alter and progress through the pattern. The setup is with 7 needles up, 7 down, creating a 14 stitch repeat. BX on Duo (LX with patterning on front bed E6) is the equivalent of slip setting on Brother. No arrow keys, Passap on N, everything knits. Brother equivalent is a row of black squares (or punched holes if applicable) for each row on the N/N knit setting. BX <– will reverse the needle selection from whatever it was immediately before the previous rows of N/N, and remain there for the full racking sequence. After the first 32-row repeat is completed, at the end of the 12 racked rows, there will then be 4 all knit rows between racking sequences, two knit rows at the top would match 2 rows knit at the start. Once again, the BX<-for one row sets up the alternate blocks of racking. I chose to start my repeat with the 930 with a cast on in racking position 10. The chart shows racking positions on each row, reversing direction after having reached #4. E6 knitters may use the same repeat, matching the Duo racking starting on 3 left to 3 right and back

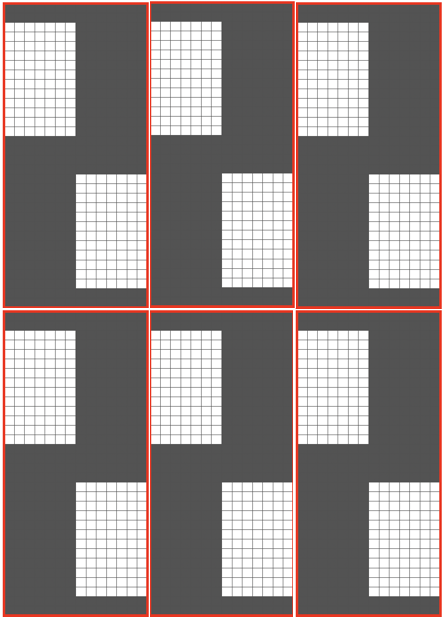

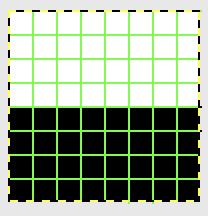

Translating Duo directions to black and white squares in order to develop a repeat for use on Brother: N/N is easy. The Duo is using buttons on the front bed and selection in response to their arrow setting to alter and progress through the pattern. The setup is with 7 needles up, 7 down, creating a 14 stitch repeat. BX on Duo (LX with patterning on front bed E6) is the equivalent of slip setting on Brother. No arrow keys, Passap on N, everything knits. Brother equivalent is a row of black squares (or punched holes if applicable) for each row on the N/N knit setting. BX <– will reverse the needle selection from whatever it was immediately before the previous rows of N/N, and remain there for the full racking sequence. After the first 32-row repeat is completed, at the end of the 12 racked rows, there will then be 4 all knit rows between racking sequences, two knit rows at the top would match 2 rows knit at the start. Once again, the BX<-for one row sets up the alternate blocks of racking. I chose to start my repeat with the 930 with a cast on in racking position 10. The chart shows racking positions on each row, reversing direction after having reached #4. E6 knitters may use the same repeat, matching the Duo racking starting on 3 left to 3 right and back The repeat viewed tiled:

The repeat viewed tiled:

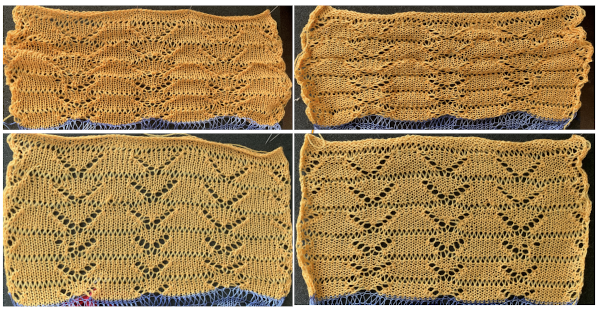

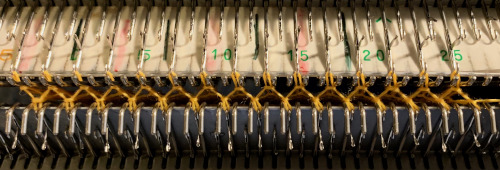

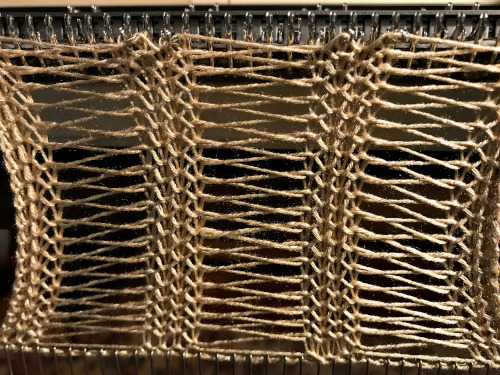

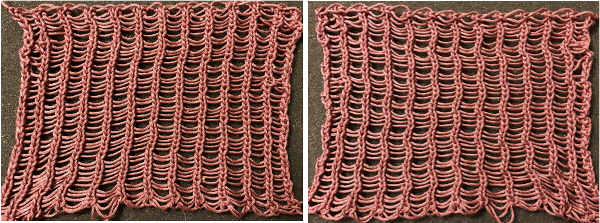

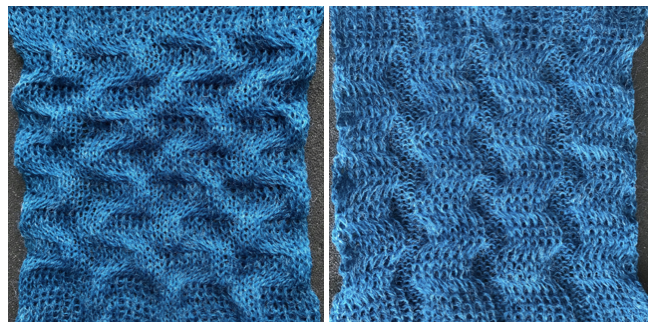

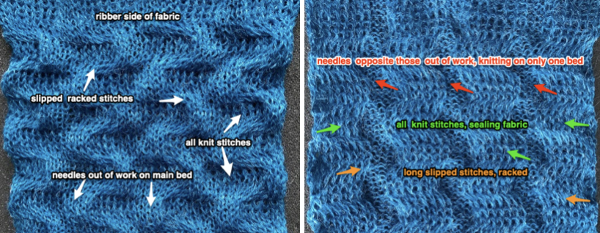

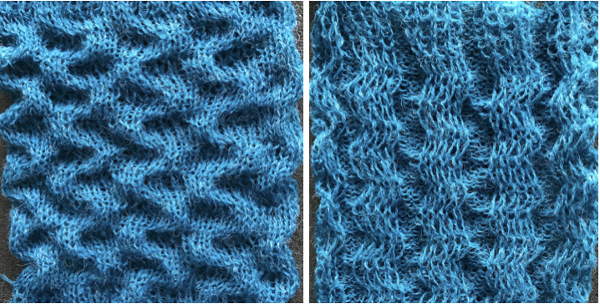

After swapping out the needle retainer bar, knitting went smoothly. On the right in the photos below, the same racking sequences and needles out of work on the ribber are used, but the knit carriage was not set to slip, so essentially, every stitch on every row on the top bed was being knit. In addition to needle preselection, one should also check the type of stitches actually being formed. One of the disadvantages to knitting ribber fabrics is that several inches may be produced before one can actually evaluate the pattern being knit by peeking between the beds.

After swapping out the needle retainer bar, knitting went smoothly. On the right in the photos below, the same racking sequences and needles out of work on the ribber are used, but the knit carriage was not set to slip, so essentially, every stitch on every row on the top bed was being knit. In addition to needle preselection, one should also check the type of stitches actually being formed. One of the disadvantages to knitting ribber fabrics is that several inches may be produced before one can actually evaluate the pattern being knit by peeking between the beds.

I will have to revisit a

I will have to revisit a

All needles used in my swatch, I began the stitch transfers down onto the ribber needles on the far left, continuing across the knit bed.

All needles used in my swatch, I began the stitch transfers down onto the ribber needles on the far left, continuing across the knit bed.  As end stitches knit on the ribber alone, a small edge weight may be required on that side. As stitches on the main bed are not worked in the slip stitch rows, they become elongated. Racking by 4 positions is not possible unless there is enough fabric so as not to pull so much that stitches will not knit off. If the yarn does not have some “give” that can make the changes in position harder, some yarns may break easily. The long stitches:

As end stitches knit on the ribber alone, a small edge weight may be required on that side. As stitches on the main bed are not worked in the slip stitch rows, they become elongated. Racking by 4 positions is not possible unless there is enough fabric so as not to pull so much that stitches will not knit off. If the yarn does not have some “give” that can make the changes in position harder, some yarns may break easily. The long stitches:

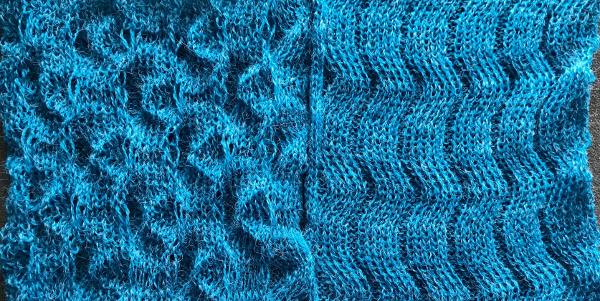

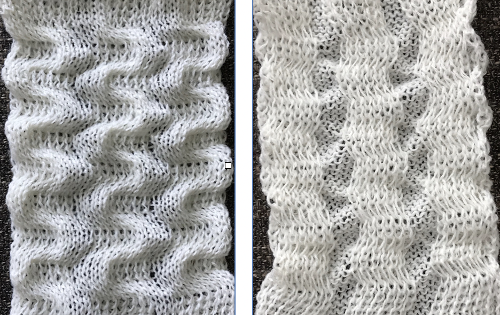

This is the swatch knit changing ribber settings to and from slip <– –> to N/N on appropriate rows. I found the method above far simpler

This is the swatch knit changing ribber settings to and from slip <– –> to N/N on appropriate rows. I found the method above far simpler  Coincidentally this morning a Duo pattern using a different setup was shown in Ravelry, and I was asked whether producing the same on Brother might have any advantages. The Duo results, shown on a

Coincidentally this morning a Duo pattern using a different setup was shown in Ravelry, and I was asked whether producing the same on Brother might have any advantages. The Duo results, shown on a

Racking is from position 10 to 6 and back just as in the previous blue swatch, after the first preselection row at the start of the following repeat sequence. I began the stitch transfers down onto the ribber needles on the far left, continuing across the knit bed. The final look will vary with the choice of yarn and its color. Both swatch sides.

Racking is from position 10 to 6 and back just as in the previous blue swatch, after the first preselection row at the start of the following repeat sequence. I began the stitch transfers down onto the ribber needles on the far left, continuing across the knit bed. The final look will vary with the choice of yarn and its color. Both swatch sides. If for some reason horizontal direction matters simply cast on with racking position on 6, and continue to and from there to 10 and back. Below is a horizontal flip of the same swatch image, a way to quickly decide whether doing so might be preferred.

If for some reason horizontal direction matters simply cast on with racking position on 6, and continue to and from there to 10 and back. Below is a horizontal flip of the same swatch image, a way to quickly decide whether doing so might be preferred.