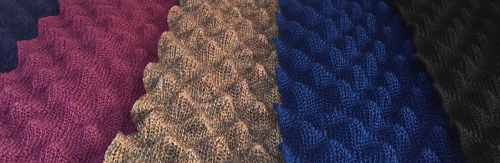

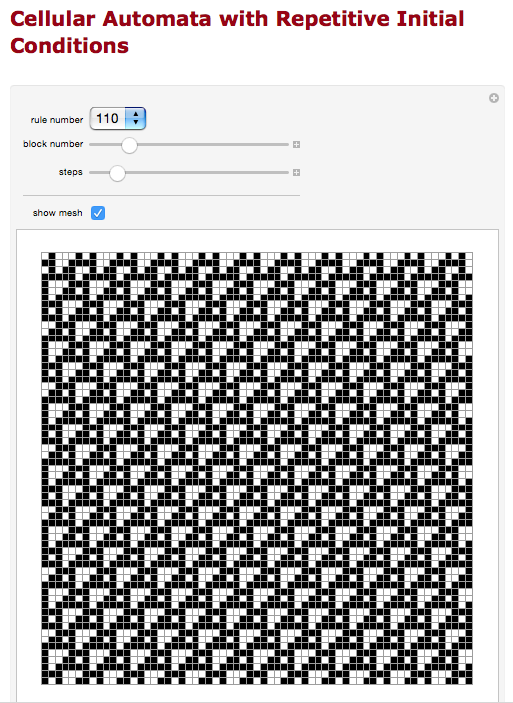

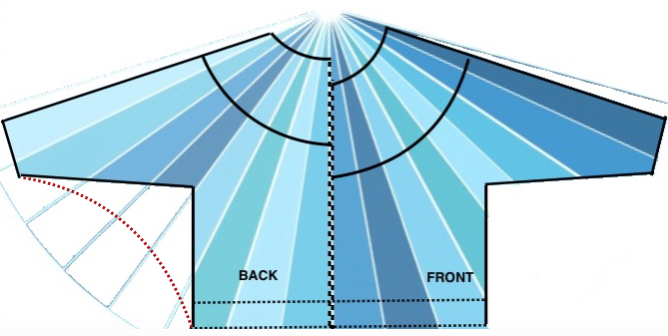

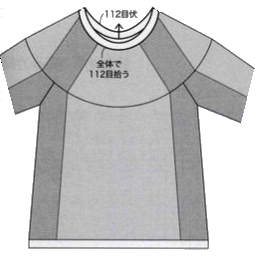

I recently came across this topic in yet another forum, so thought I would share some of my thoughts on it. The technique involves different patterns on 2 opposing beds. Table for 2 offered one option for programming 2 different knitting machine beds to achieve reversible DBJ or true tubular fair isle. I will be addressing Brother settings for the moment. Things to consider: the piece will be double thickness and 1.5 times the finished weight of one knit in single bed FI. FI technically knits 2 colors for each design row, the ribber at least one for the first piece here, so thinner yarn is probably best. If the main bed is creating a 2 color slip stitch, whether one color at a time (DBJ) or 2 colors together as in traditional FI, the fabric will be shorter and thinner because it gets pulled in by the shorter floats of yarn in areas that do not form knit stitches with that color. Generally, in FI it is good to have end needle selection on so that the second color gets caught at the edge, and the design does not separate from the rest of the knit at the sides. I knit my sample using KCI on the knit carriage. The ribber is going to knit one row for every 2 passes to complete each design row by knit carriage, so some adjustments in tension both beds need to be made for each side of the tube to be balanced. If the goal is to have the tube open at the bottom, I like to start in waste yarn and begin tubular while leaving a long end of the first color used so “bind off” can happen by sewing or crocheting the open stitches when the piece is done. The same can be done at the top of the piece, and both ends will match. Setting the needles point to point during tubular knitting will diminish any gap at the sides of the knit if the tube is made in the traditional setup. Since only one-bed knits at a time, needled will not come in contact even if directly opposite.

This fabric shares features with quilted fabrics, except there are no areas where the fabric gets joined to make pockets (needles on both beds knitting on any one pass of the carriages), the goal here is a continuously open tube. Minimal manipulation of carriage settings can be achieved in color separating for the specific fabric. My previous posts on quilting: 1 and 2, and on color separations for DBJ

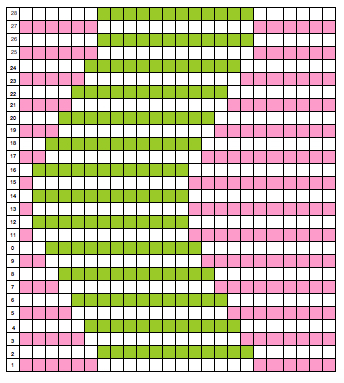

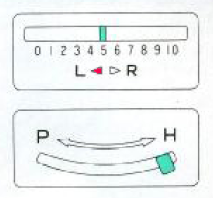

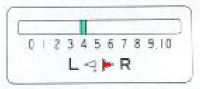

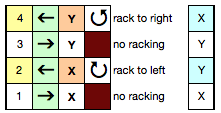

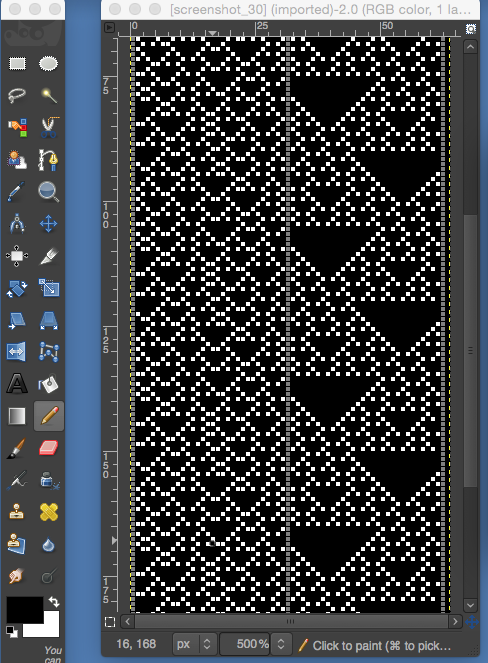

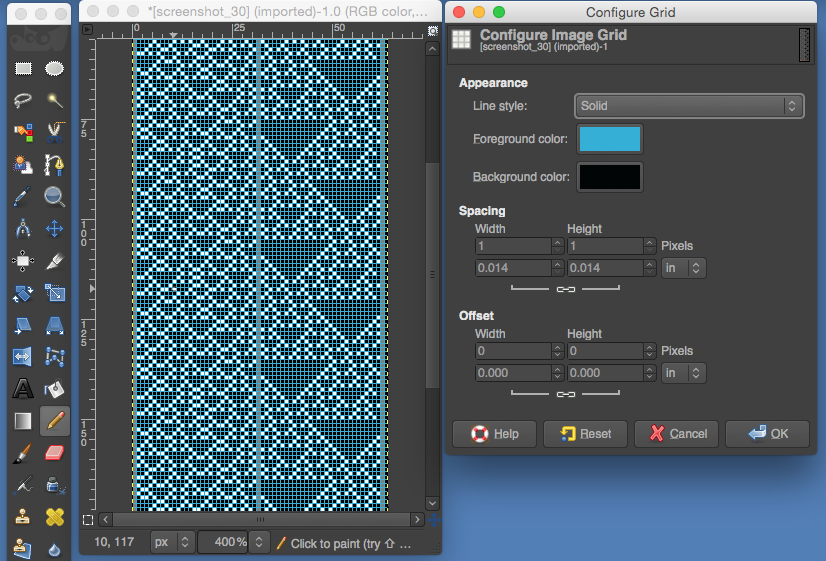

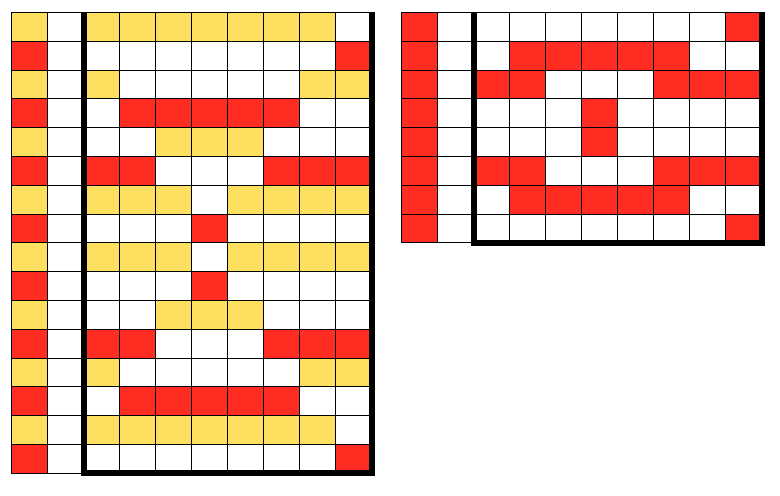

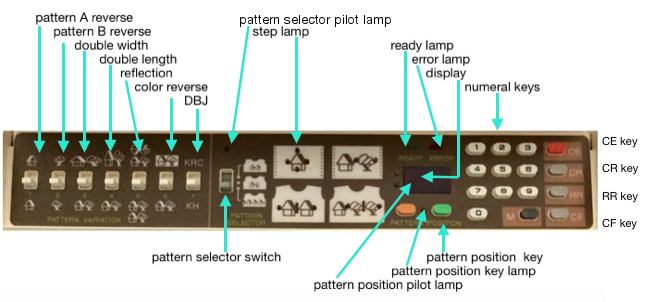

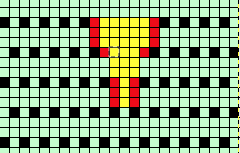

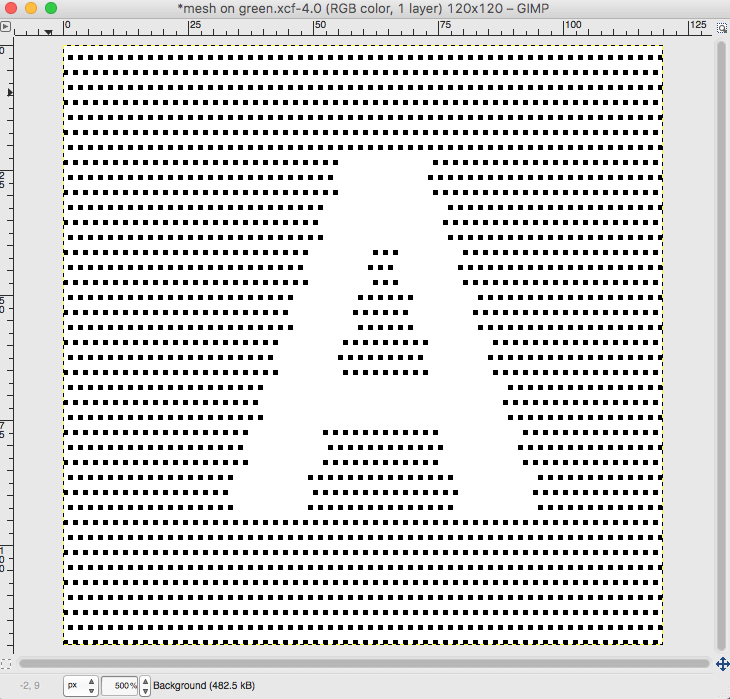

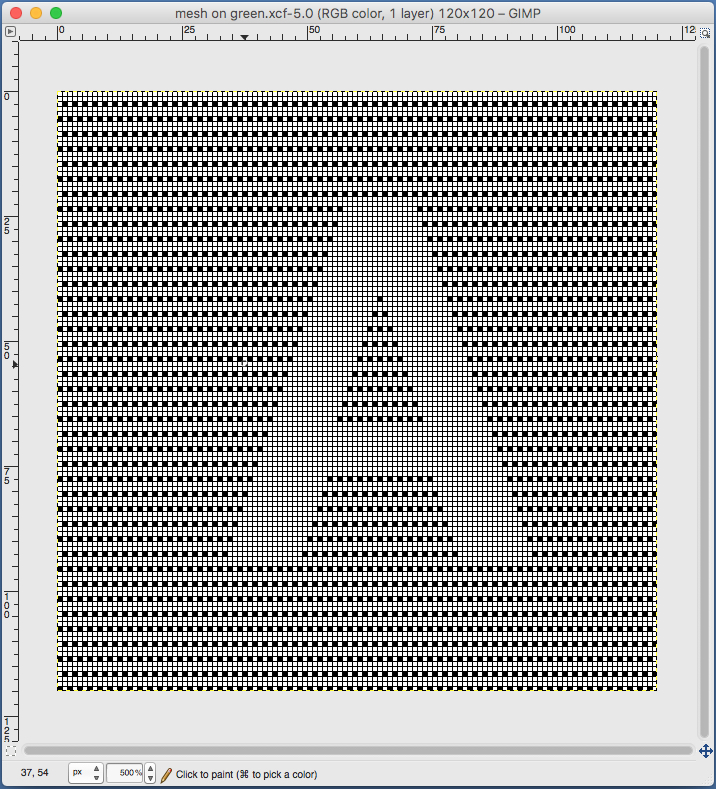

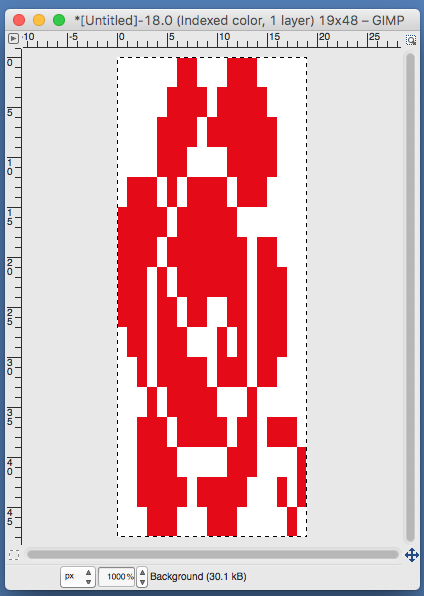

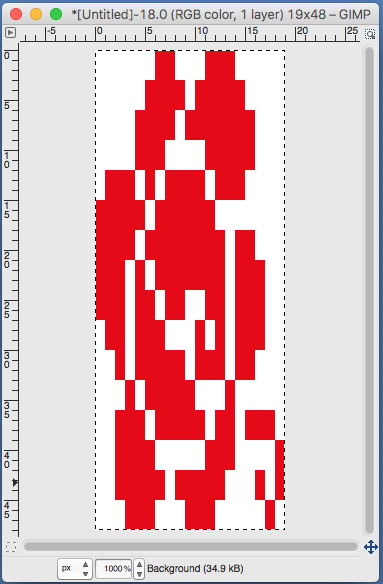

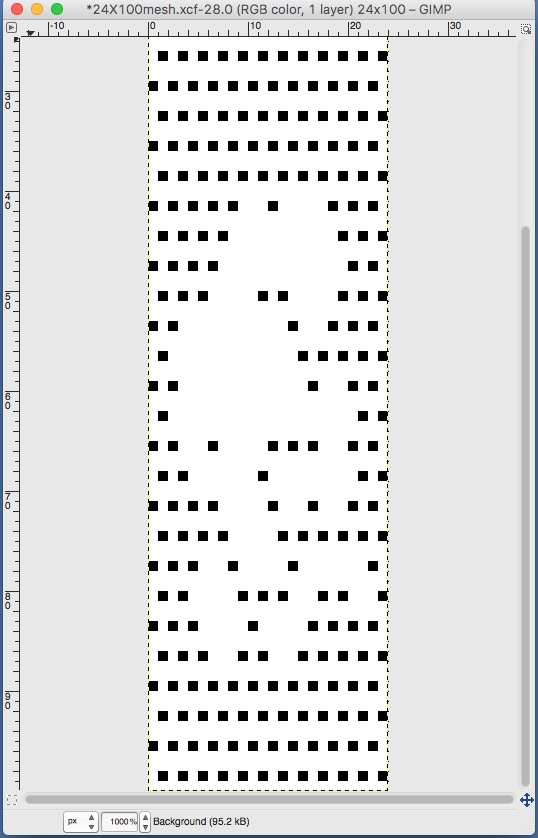

It is always best to start with a simple design that allows one to recognize needle selection. Long verticals can separate at their edges if knit a single bed, but I went for a simple pattern of squares to test out my premise and winged it. Thinking color 1 knit left to right, slip right to left and ribber slips when main bed knits right to left, knits when main bed slips left to right. The all blank rows indicate the main bed slipping the width of the involved needle bed. The same applies after any other consecutive color change. My mylar repeat, free drawn  End the circular cast on/ waste knitting start and begin with opposite part buttons pushed in with COR; set change knob to select the pattern (KC I), to prepare for the move to left toward color changer. The main bed only will knit. With main bed set to knit <–, needles for the first row of the pattern are selected, but all stitches knit. The ribber needs to slip <– completing the circle. If in doubt, push up both part levers on the ribber.

End the circular cast on/ waste knitting start and begin with opposite part buttons pushed in with COR; set change knob to select the pattern (KC I), to prepare for the move to left toward color changer. The main bed only will knit. With main bed set to knit <–, needles for the first row of the pattern are selected, but all stitches knit. The ribber needs to slip <– completing the circle. If in doubt, push up both part levers on the ribber.

the start of the tube, needle selection for first pattern row

the start of the tube, needle selection for first pattern row

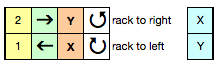

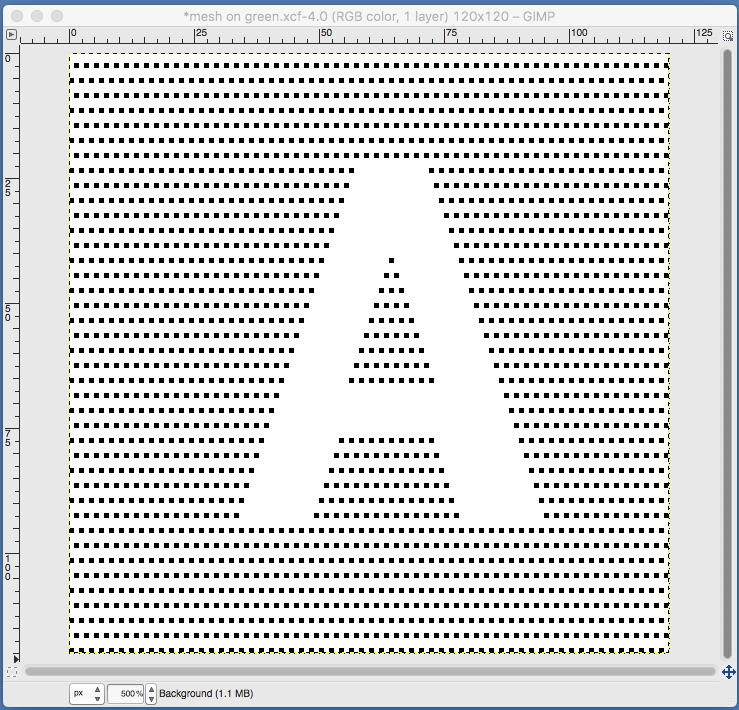

after the color change, with COL, change settings once more. The main bed will now knit to right and slips to left based on needle selection, while the ribber now slips to R, knits to L (the goal here is simple stripe)

the start of a tube is evident if the ribber is dropped a bit

the start of a tube is evident if the ribber is dropped a bit  the tube dropped off the machine

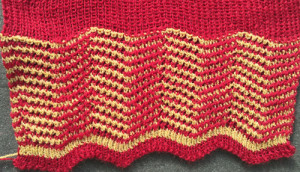

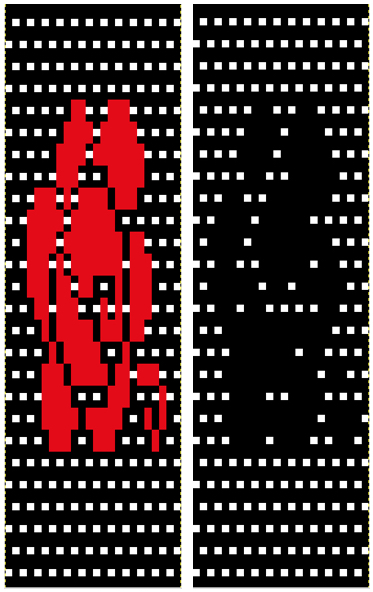

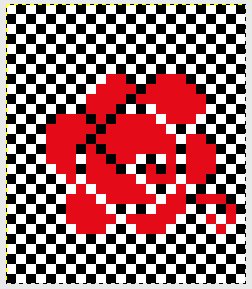

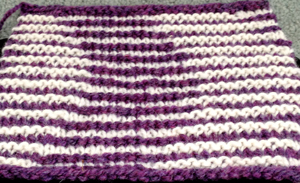

the tube dropped off the machine  the FI created on the main bed

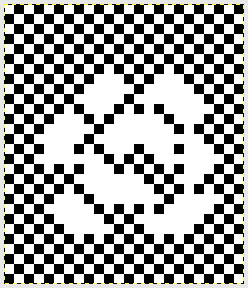

the FI created on the main bed  the pattern on the reverse, created by ribber

the pattern on the reverse, created by ribber

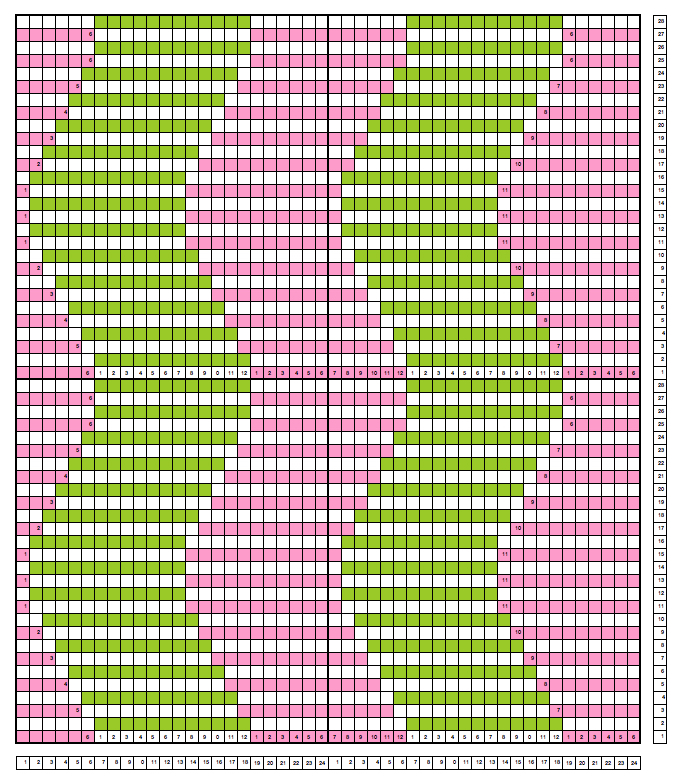

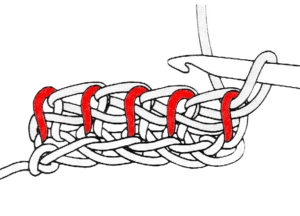

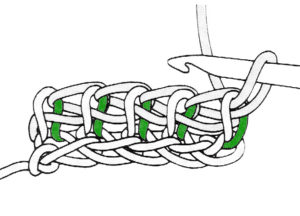

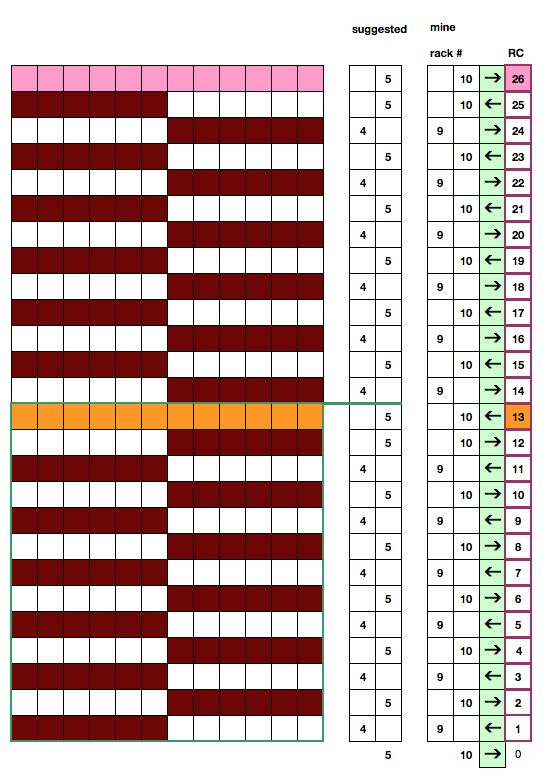

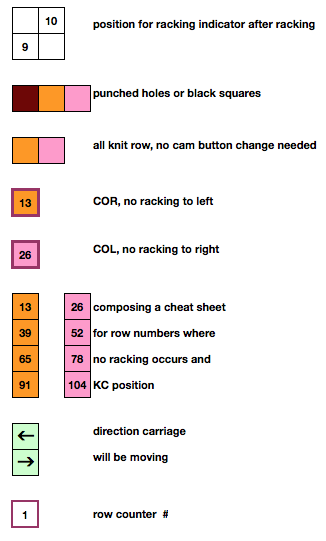

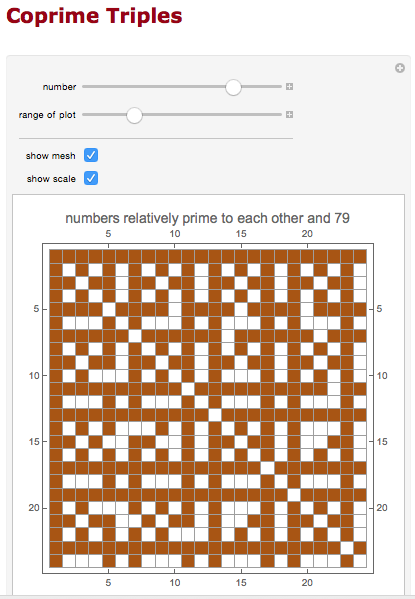

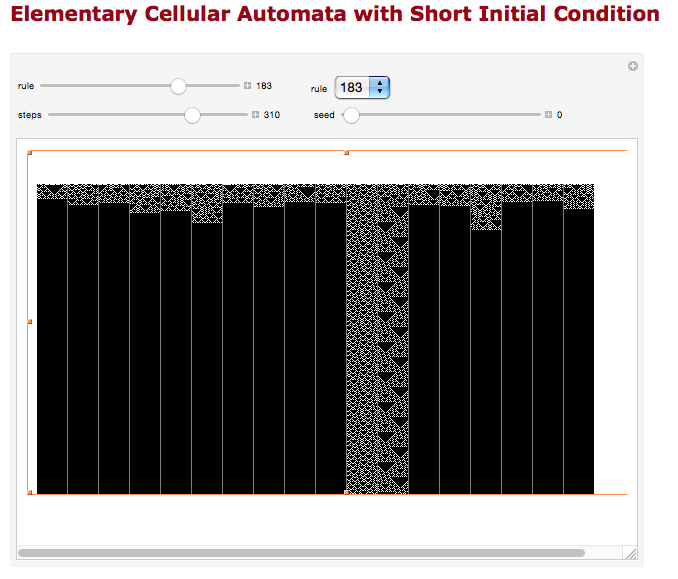

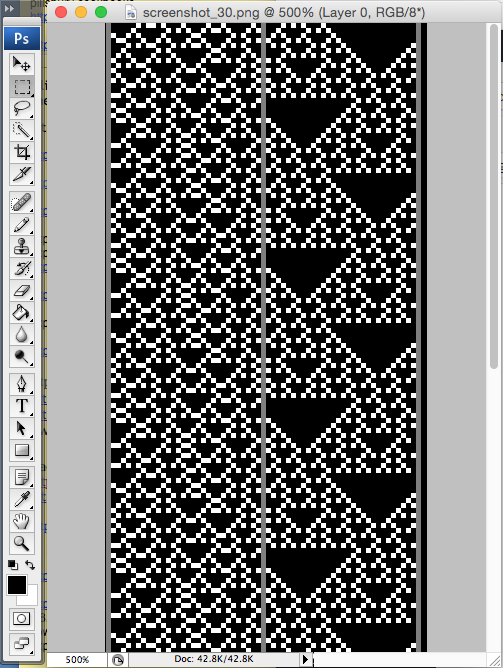

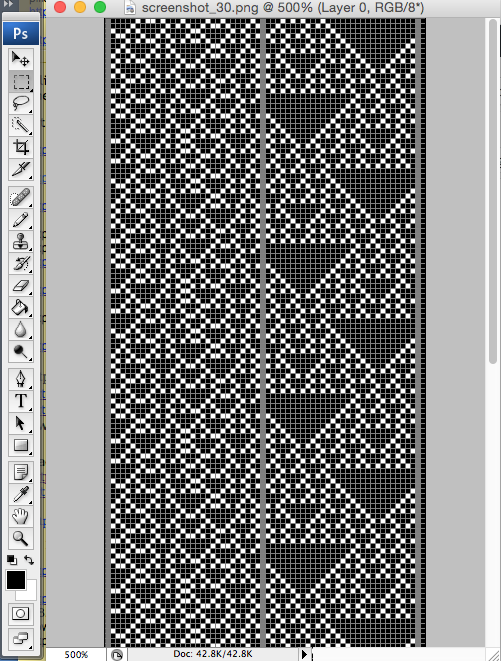

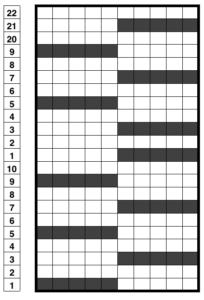

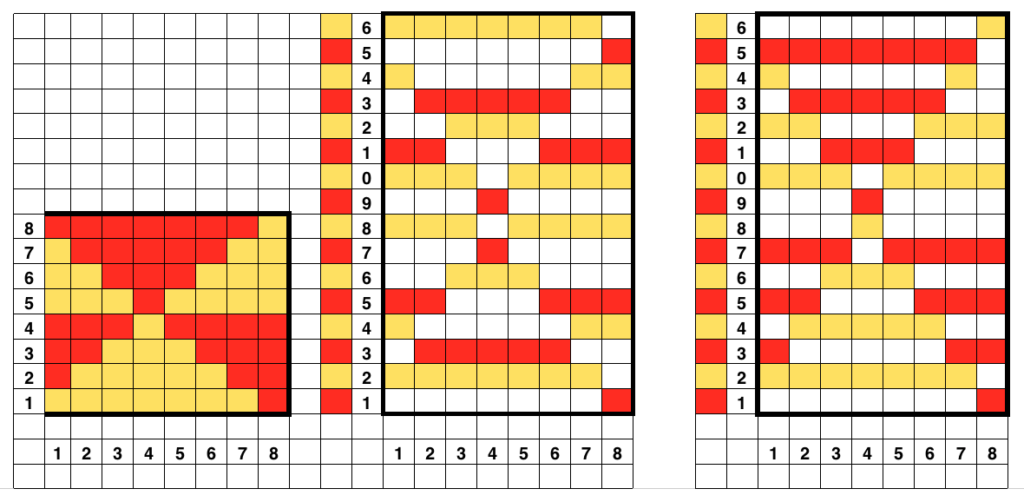

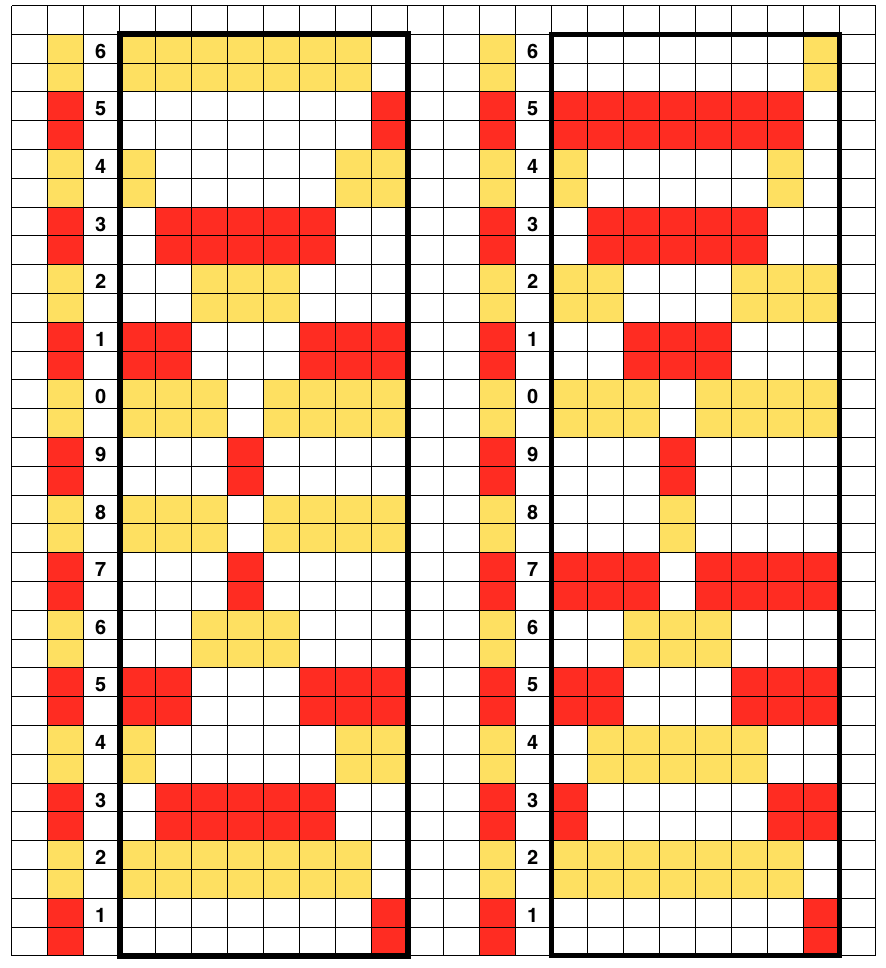

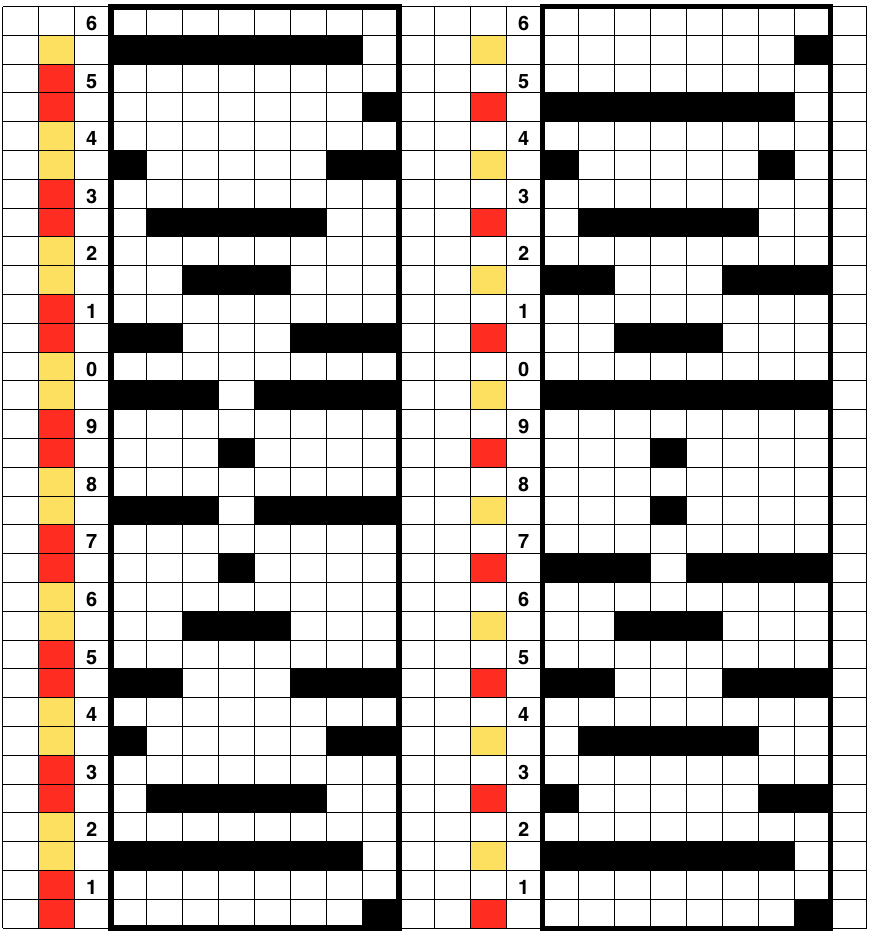

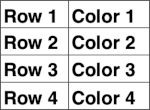

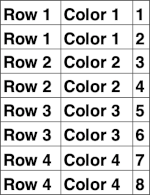

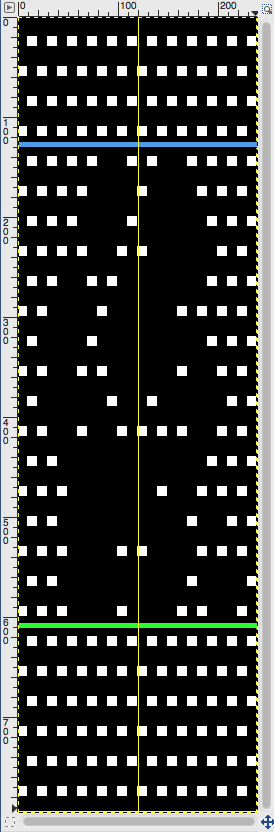

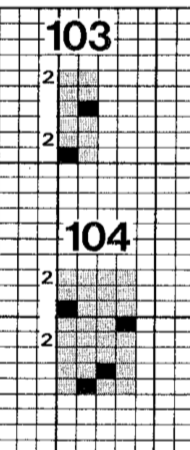

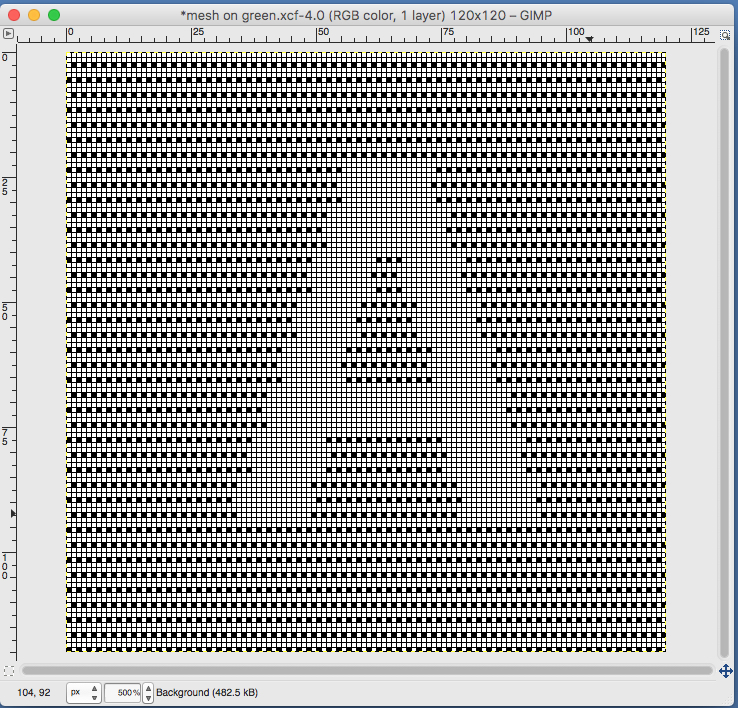

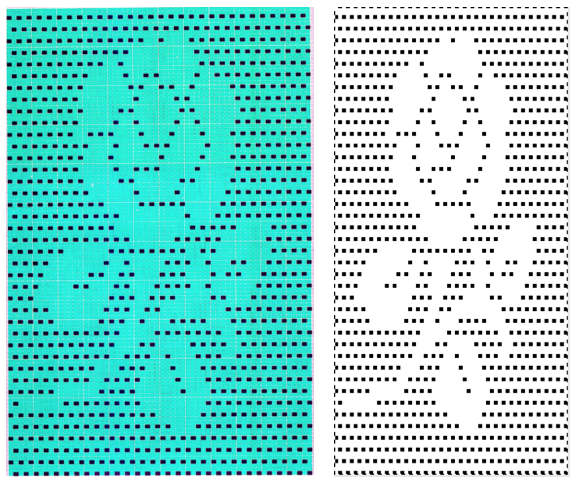

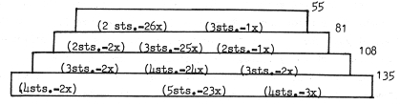

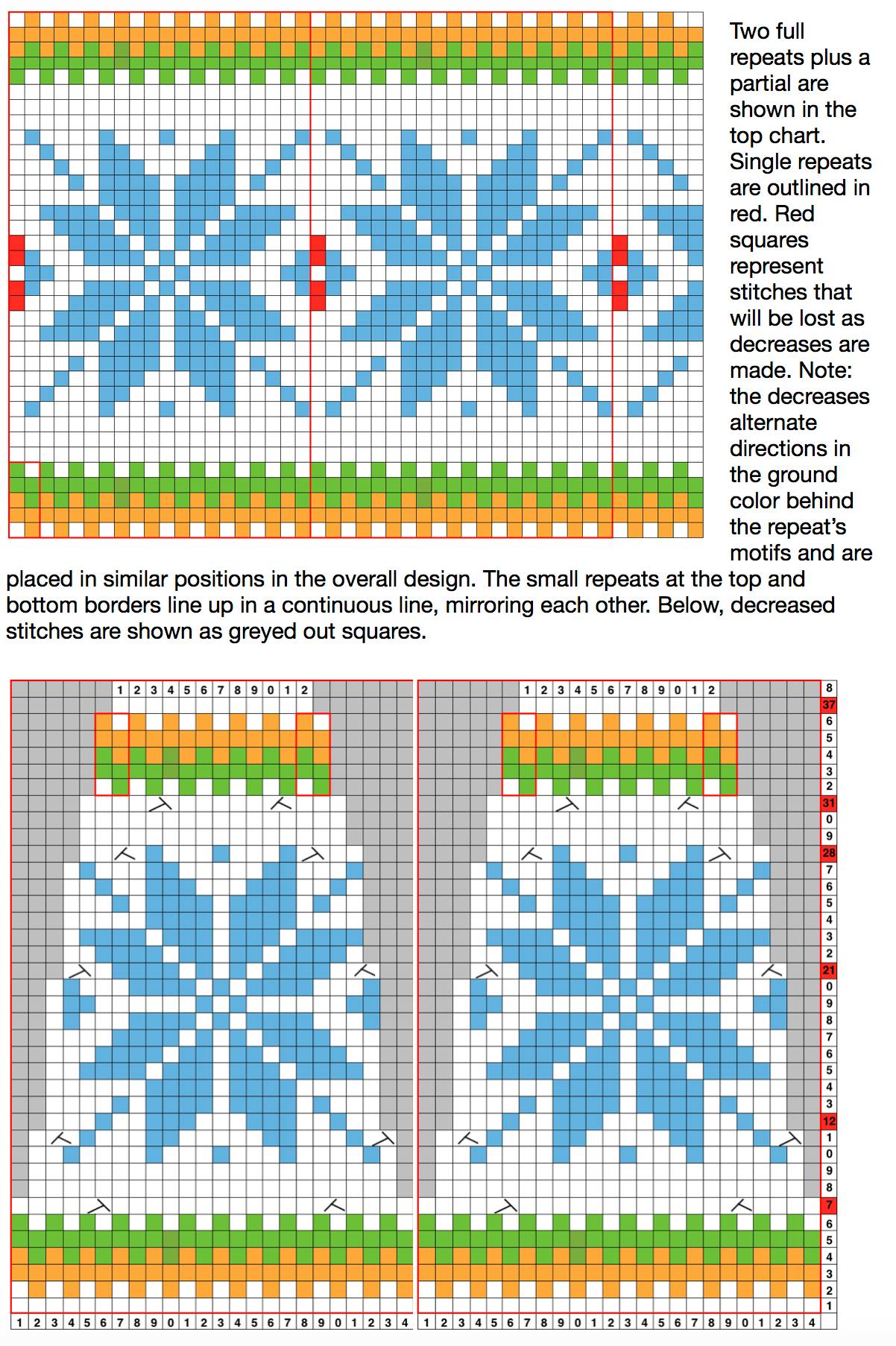

It helps to analyze the carriage actions on knitting the repeats. These charts illustrate the 2 colors knitting alternately with each pair of carriage passes. With any knitting motif, it is worth testing repeats consecutively in height and width to get a sense of what will take place using them on the finished knit. Here 2 lengthwise repeats are shown. The pattern could be planned to start the repeat with the area outlined in red on the right, and a full block would occur at the start of the tube. A bit of editing would make all rectangles equal in height.

So now that I have some blocks, what about other patterns and shapes? ……

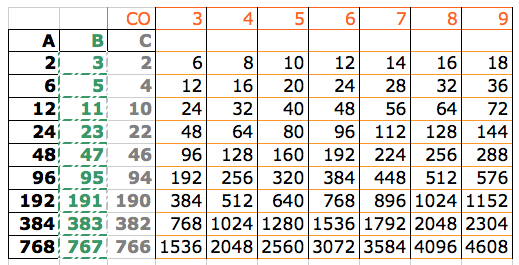

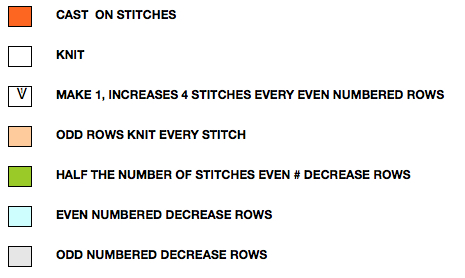

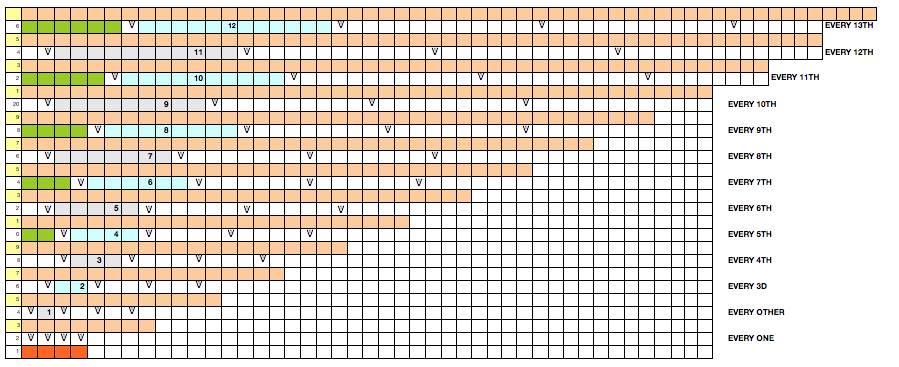

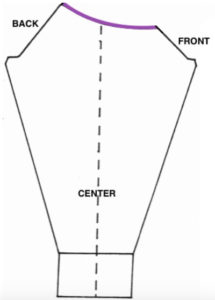

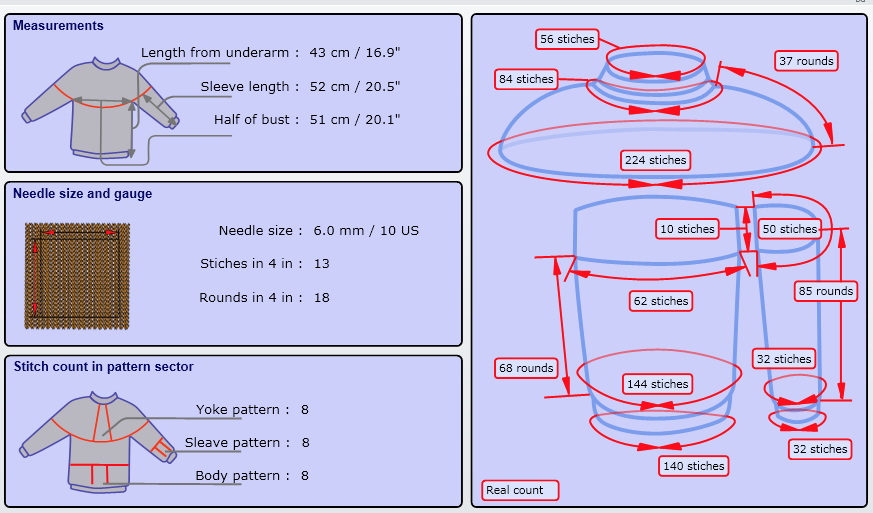

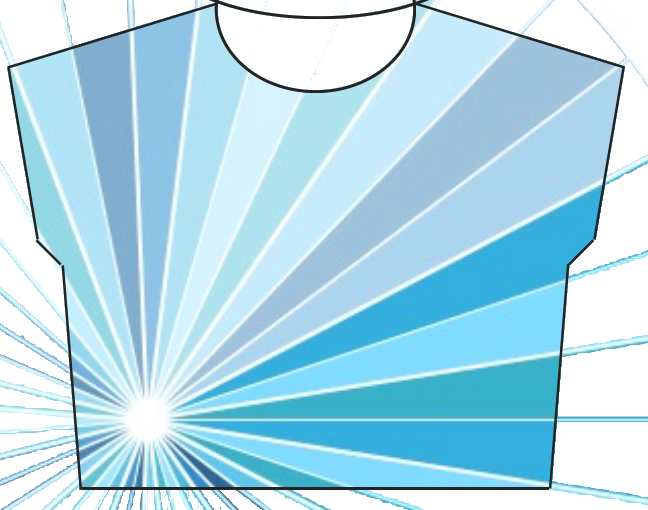

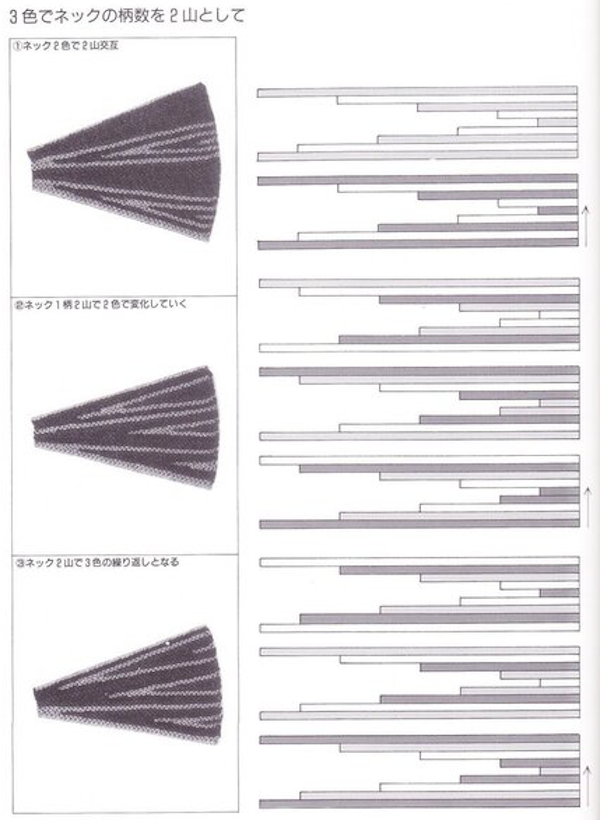

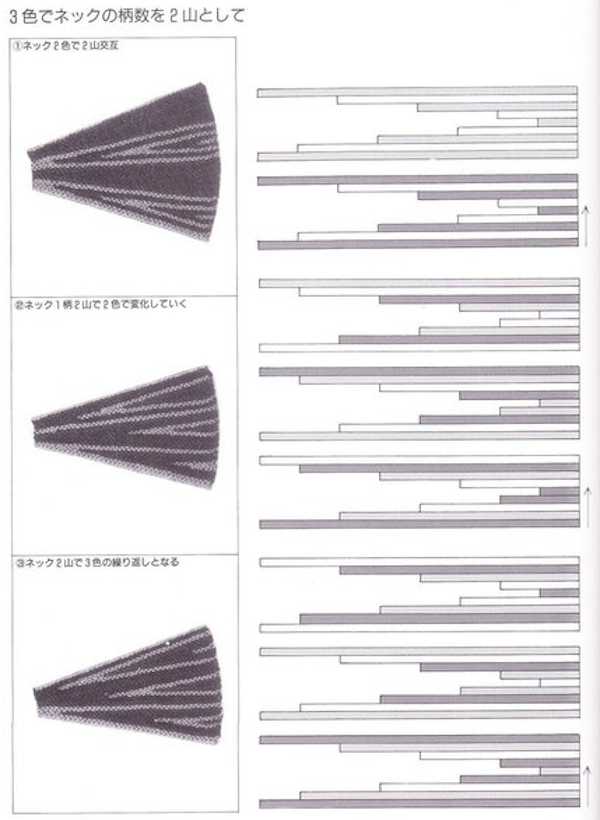

In a previous post with exercises on DBJ, 2 separations of the triangular shapes below were offered. Testing the idea of using pre designed jacquard separations for knitting tubular fair isle, I chose to use the 2 alternatives presented. The related information is available in PDF format for punchcard and electronic machines

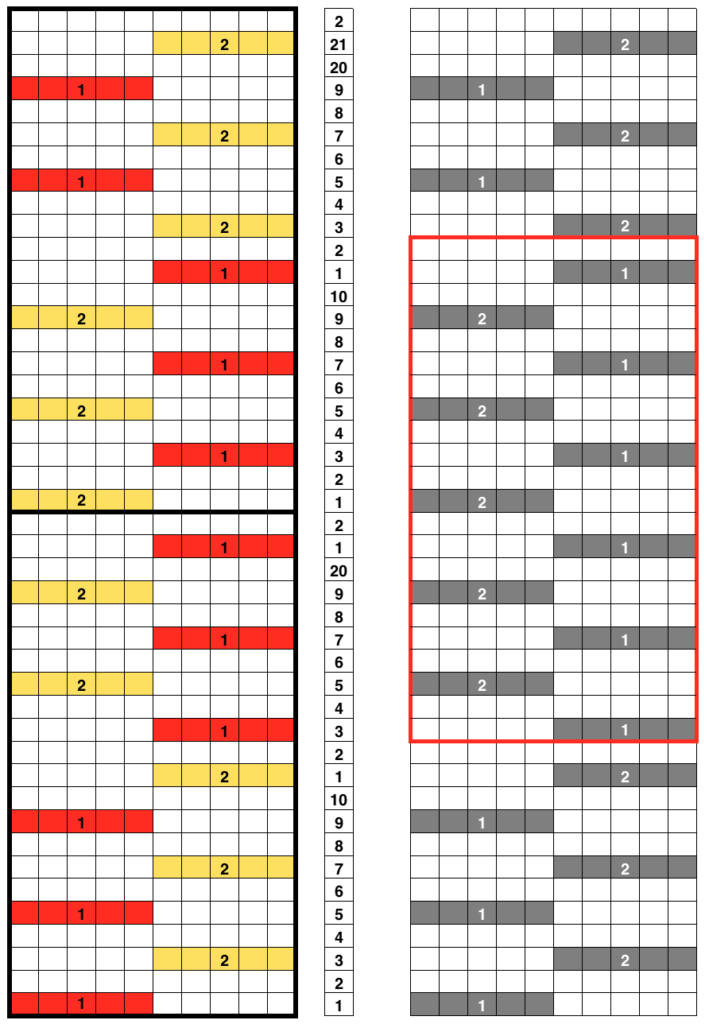

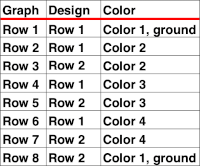

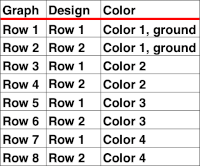

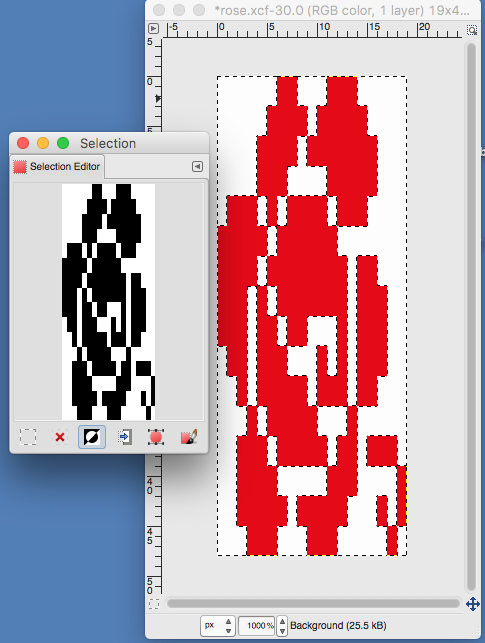

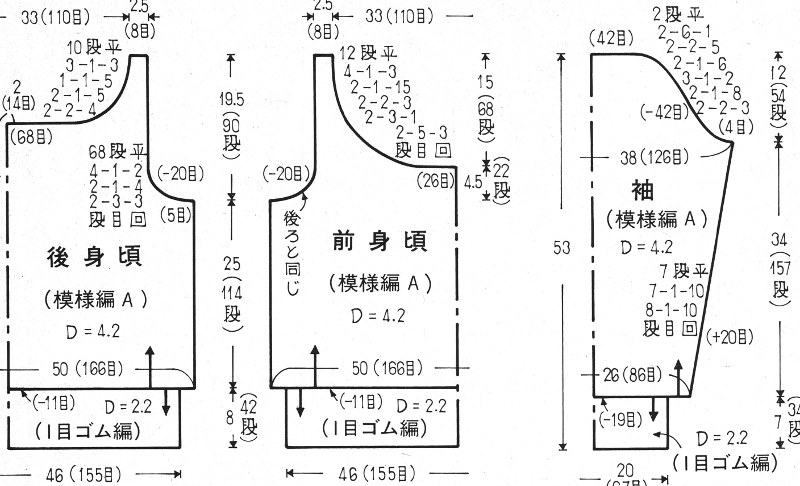

Here we have the motifs, and 2 methods of color separation for DBJ, charted, drawing each color design row only once

The middle image shows the method for separation achieved automatically in Brother by using the KRC button when using only 2 colors per row. It causes the least (if any) elongation of the motif. Each design row knits only once, programmed as is. If the KRC button is used, none of the other functions including double-length are allowed. The separation on the right is the most common color separation, actually knits each design row twice, which elongates the motif. As drawn, it would need to be programmed double length. If the knitting is representational, an adjustment may be needed in altering its height prior to downloading it for knitting. I used both separations above drawn on an old mylar for my second tubular FI attempt, sticking with my thin yarn, and working in small swatches while testing technique ideas. My initial premise was to knit each row twice using double length. The preparation was as already discussed. After the color change and resetting the carriages COL, the first row slips on the ribber, and the main bed knits the first design row in the alternate color, seen here in white. As in single bed FI, floats are created in that color between needles knitting it  with COR, before traveling back to left for the color change, return all main bed needles back to B position with a ruler, ribber comb, or any preferred tool, so that only the ribber only will knit, keeping the knit tubular as you travel back to the color changer.

with COR, before traveling back to left for the color change, return all main bed needles back to B position with a ruler, ribber comb, or any preferred tool, so that only the ribber only will knit, keeping the knit tubular as you travel back to the color changer.

COL: change colors and repeat. Here are my trial tubes, again in too thin a yarn, but proofing the concept. My mylar was ancient, marked in #2 pencil on its reverse, and I can see a couple of spots that need darkening, but that is not a concern for this exercise

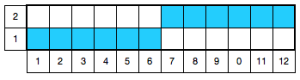

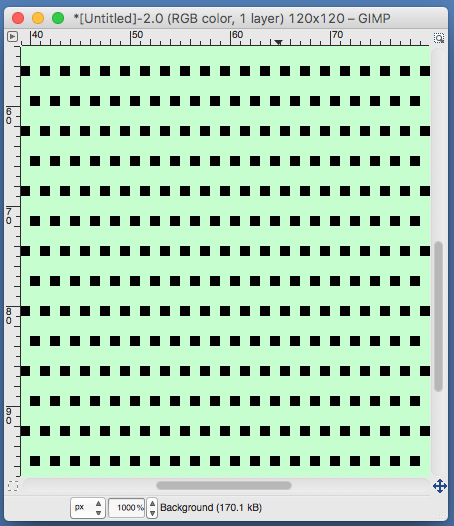

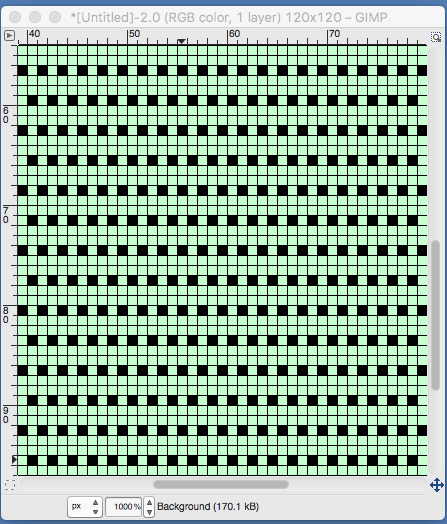

Adding color and expanding the charts to match the B/W versions  each row elongated X 2

each row elongated X 2 what knits when setting machine for tubular; in the swatches, the blank rows were achieved by manually pushing needles back to B as shown above

what knits when setting machine for tubular; in the swatches, the blank rows were achieved by manually pushing needles back to B as shown above  this shows what happens when the first separation is collapsed into what actually gets knit by the carriages in this technique

this shows what happens when the first separation is collapsed into what actually gets knit by the carriages in this technique

and the result in repeat in B/W like my swatch

and the result in repeat in B/W like my swatch

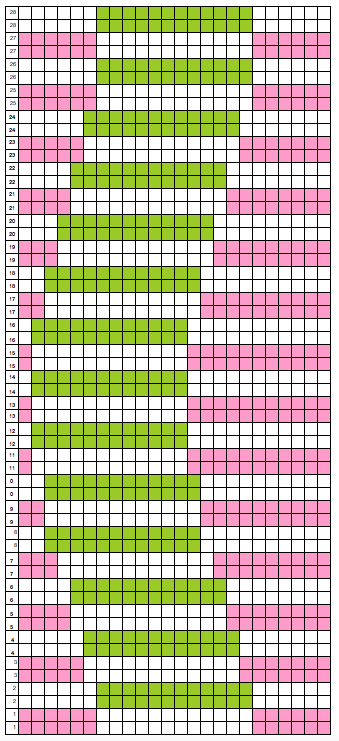

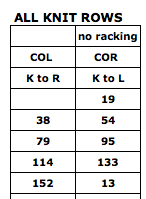

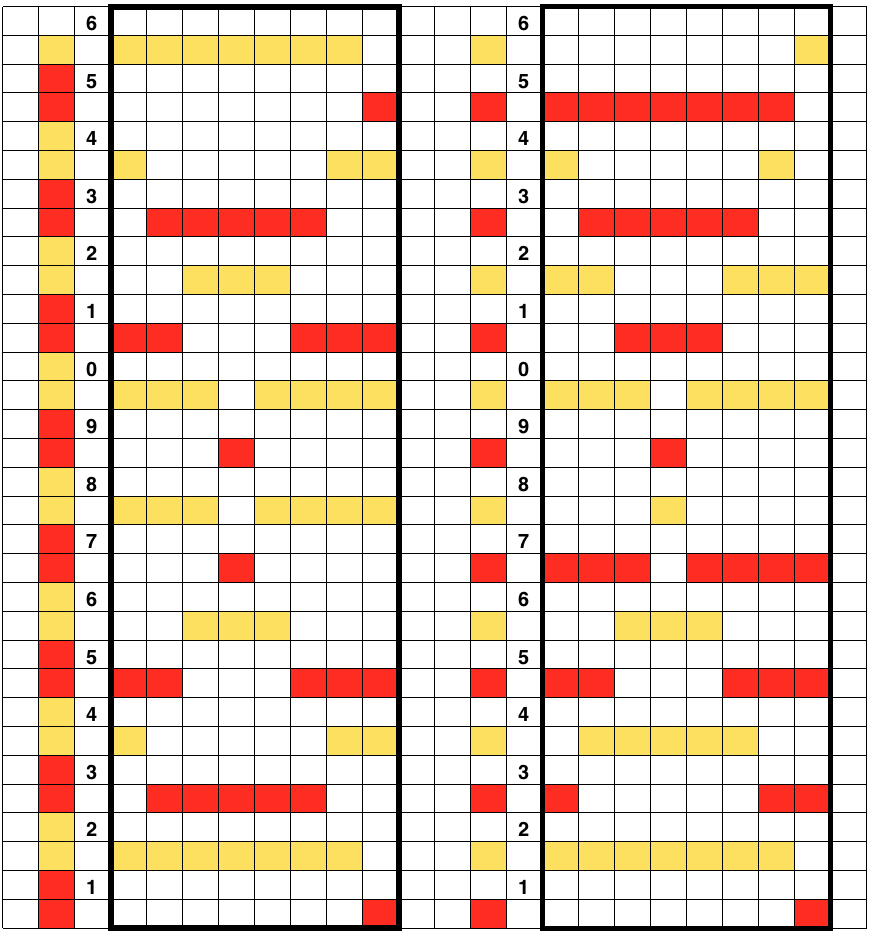

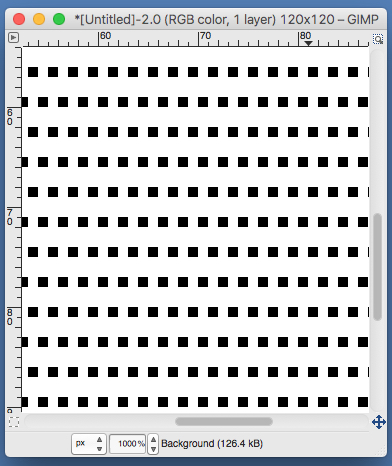

Both elongated repeats are reduced to black and white squares below, with blank rows, included to let the carriage do the work, without having to push any needles back to B position, KC set to slip <– –>. I often work out my separations in color, then fill the colors in with black and white. It is easier for me to draw the black only squares on the mylar or to enter them as pixels than trying to do that from a colored graph. I am now charting in Mac Numbers, no longer have access to Microsoft Office on my new Mac.

DBJ patterns predawn for punchcard machines or provided as charts for electronics may all be used for the FI pattern. The first separation method will yield a surprise. The second method if each row is illustrated only once needs elongation. In separations where the work is done for you, producing a result like the elongated swatch on the right, the pattern is ready to go.

Creating the separations by hand is time-consuming, having software separate the motif, eliminating that design time is quite helpful and more error-proof.

The ribber needle selection can be altered to produce patterning with hand needle selection, or by changing the slip lever positions as frequently as every row. That is a post for another day. That said, some things to consider: my own DBJ scarves often involve more than 1200 rows of knitting. The number of carriage or lock passes involved to achieve the same length is increased exponentially should I choose to knit the same designs tubular. If any needles on both brother beds wind up in work at the same time prior to the next row knit, the fabric will seal closed in those areas (another range of lovely fabrics, but not the plan here). For the ribber to knit in any other pattern than an easy stripe, one needs to either select needles by hand or add changes in levers possibly as often as every row. If multiple rows are knit on the ribber and then in turn on the main bed, one is actually creating a tapestry technique and there will be small slits at the sides of the knit, depending on the number of rows knit on either bed. It is truly helpful if the software in use or the machine’s console is able to recall the last row knit and to take you back to that spot if knitting is interrupted or put off for another day. That is one of the very convenient features of the Passap system providing the battery is still holding the charge. The latter also performs the same function and returns to the correct pattern row if one has to unravel rows and the number of unraveled rows is entered into the console. If long, nonrepetitive in length designs are in use and need to be downloaded in segments (wincrea has such limits), a warning noise when the end of the pattern repeat is reached would be nice to have. In my opinion, it’s fun to achieve things because we can, then it becomes a personal choice as to whether the process is worth it, and under what circumstances to use it. My own accuracy when a lot of hand manipulation or other details are in use has faded with my increasing age and decreasing attention span. Others can tackle the same with great success, such as seen in some of the wonderful all hand transferred complex machine knit laces found on Ravelry, and then there was the man who used to tour machine knitting seminars with a MK sweater he had made for himself in a fine yarn that incorporated over 3,800 (yes, thousands) cables, weaving in and out of each other and in turn in and out of crossing diamonds in a fine yarn (no, no one I know of actually counted them, the count was accepted on faith).

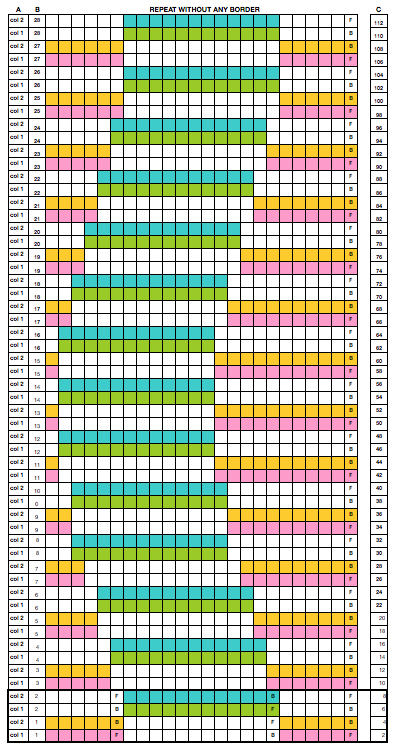

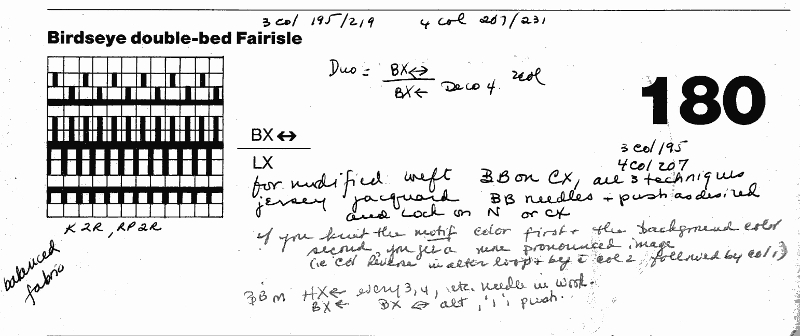

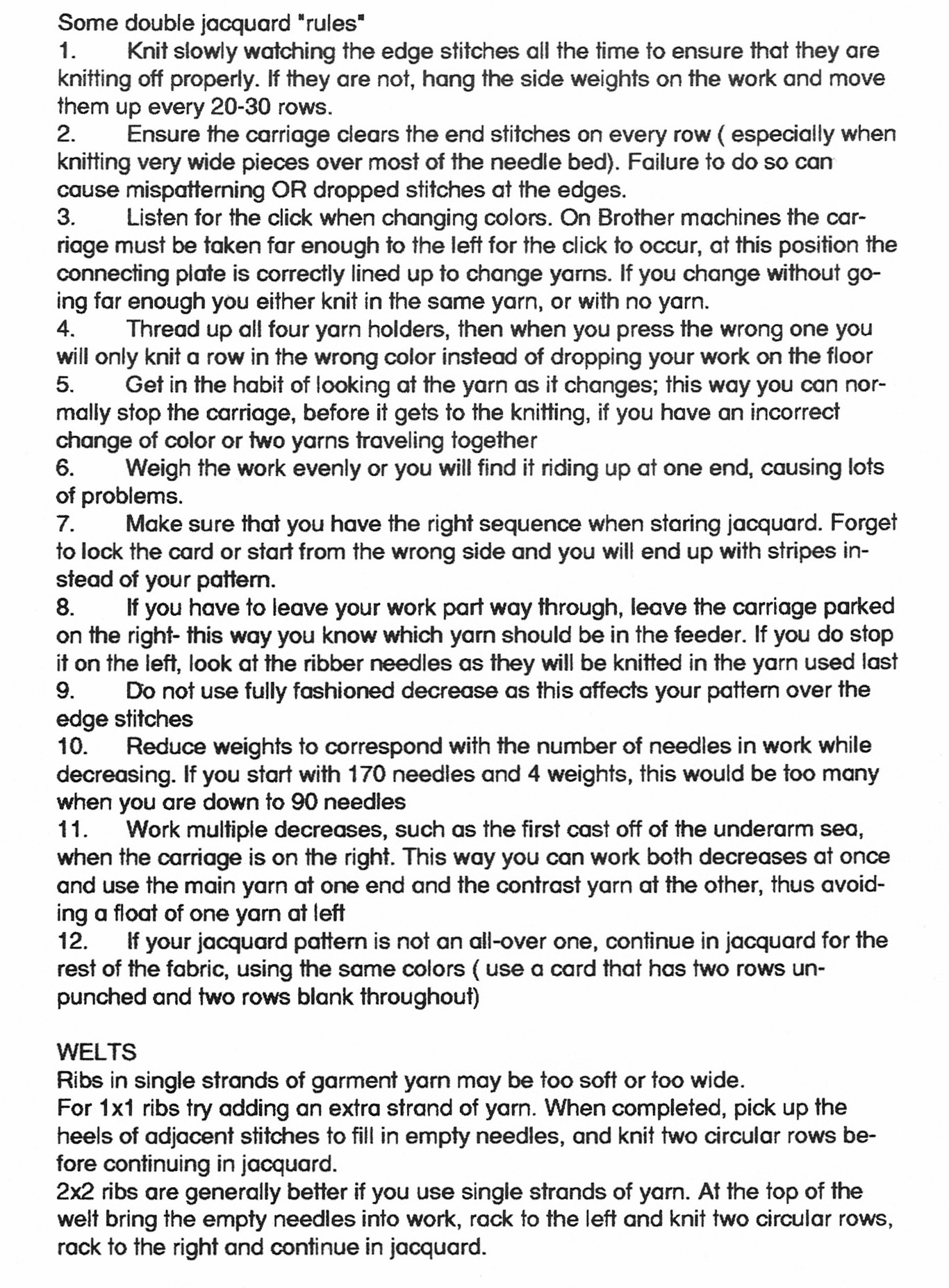

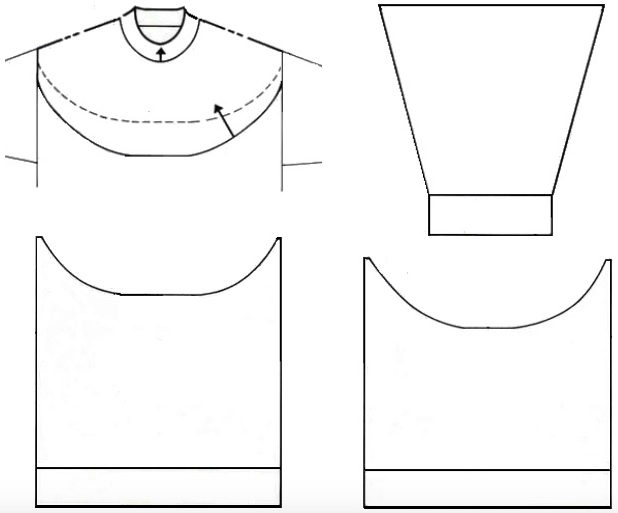

The Passap console has built-in color separations for tubular knitting. As with Brother, the simplest fabrics are in one color. For one-color fabrics, CX/CX (the equivalent result in Brother happens by using opposite part buttons on either bed) is used on both locks.

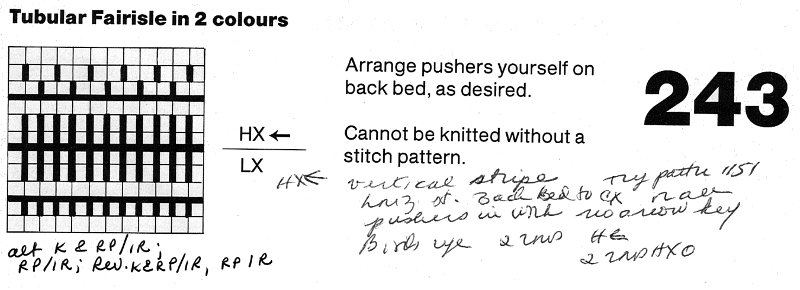

For 2 color fabric, the DM 80 front lock (carriage term equivalent) is set on HX <– while if using the E 6000 one may select KT (knitting technique) 243, with the front bed set to LX (slip). I have had very limited experience with the DM80 decades ago, can only speak for the E6000. The front bed is programmed as for any other pattern. With the back lock set to CX (no pattern) or HX (pusher selection for pattern), the function is fixed, the front bed knits to left and slips to right, the back bed slips to left and knits to right to create the tube

Horizontal stripe: is the simplest to execute: set the back bed on CX, or put all back bed pushers in work position and set back lock to HX, no arrow key. Pushers up knit, pushers down slip. (in Brother set the appropriate ribber lever to slip in one direction)

Vertical Stripe: “automatic”, bring pushers under every back needle into one up, one down, alternating in work and in rest. Set back lock to HX, left arrow key <–, changing color every 2 rows. The same needle selection is in the same location with each color change, creating the stripe

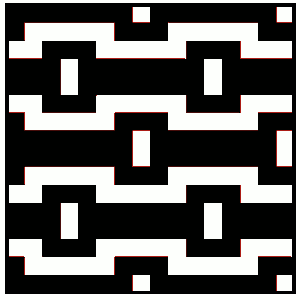

Birdseye backing, manual tech involved/ lock setting change involved: set back bed pushers alternating one up, one down, thus alternating in work, out of work. Knit 2 rows with the lock on HX, no arrow key, and 2 rows with the locks on HX <–.

Solid color backing is possible: set the front lock is set to LX <–” (slip <–”). When Tech 243 is in use, after the setup rows are completed, the console gives the prompt for setting up the pushers, all in work, and for HX <–”on the back bed. The result is that for 2 rows in the lining color, stitches knit alternately on each bed. The front bed then knits alone in turn for 2 passes; the color yarn in use creates a float the width of the knit as the locks return to the right, making it the least acceptable variation, and an unbalanced knit. The set up is different for both quilting (BX <–/LX) or solid color backed DBJ from tubular FI created in this manner.

My Passap manuals have been well used, often technique numbers are surrounded by notes in my scrawl. Techniques perform the color separations for the specific fabric, the accompanying diagrams and directions are suggestions for swatches provided as well in the alternate accompanying manual. Lock settings can be set to suit i.e. tuck substituted for slip, etc. The separation is fixed, but all lock settings are in the hands of the knitter.

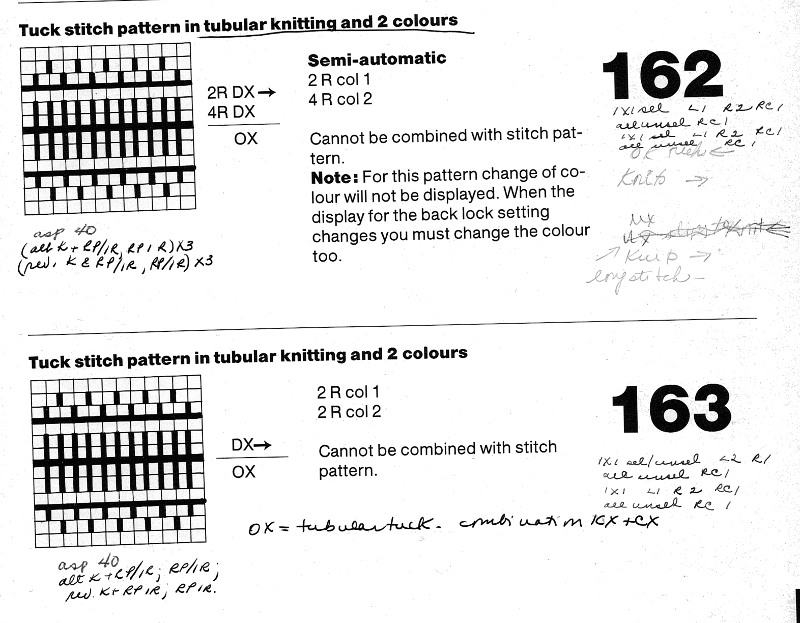

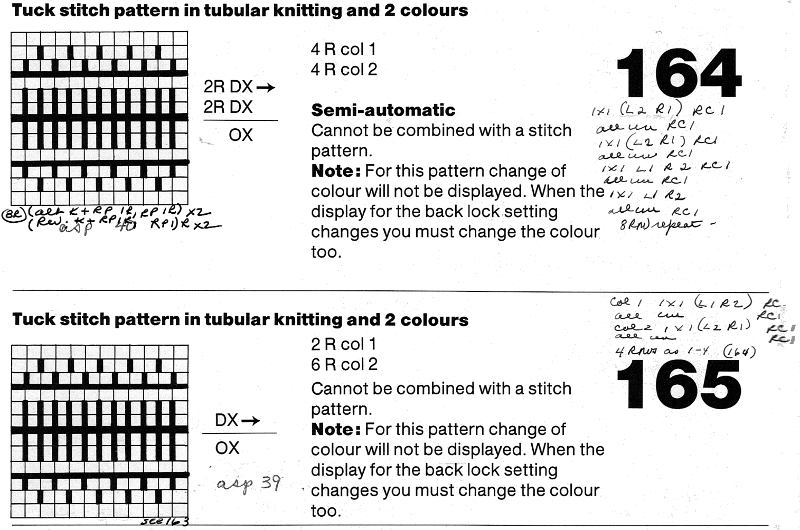

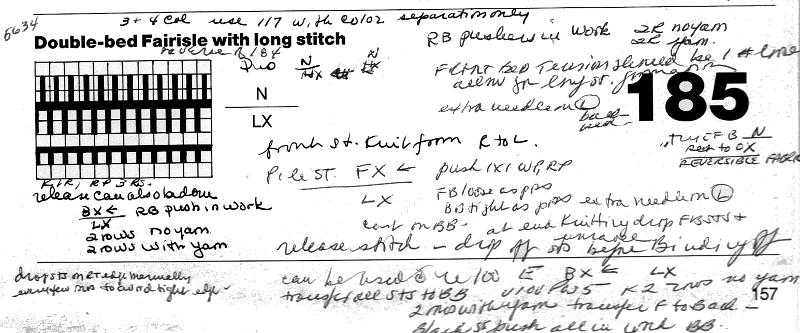

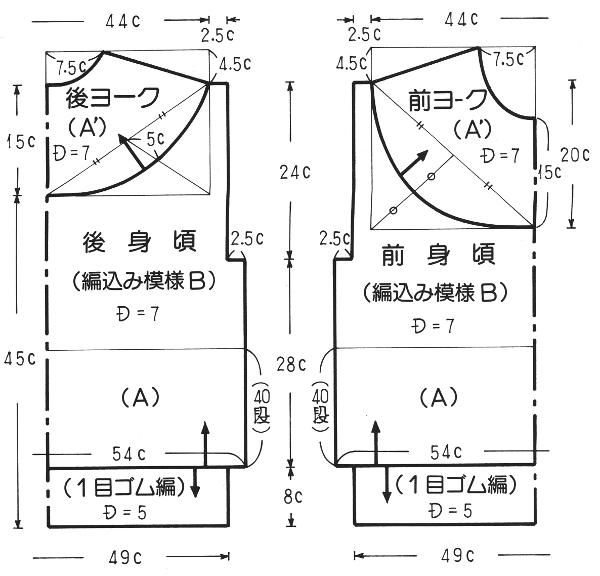

2 color circular tucked designs are produced using techniques 162-165, with the frequently unfamiliar settings using OX/DX. As with many other techniques, some may be used with stitch patterns, some not, but if you understand what is happening front bed patterning could be converted to the automated pusher or needle selection by entering a planned color separation as a pattern. OX is a combination, tubular tuck setting, paired with DX. OX is a combination of KX (tuck in the pattern) and CX (circular). DX is the tubular tuck setting for the back bed. OX and DX will knit needles with a pusher (needle selected on Brother) in work (selected needle), and tuck on needles with no pusher in work (non selected needle) moving from right to left. From left to right the front bed is not knit any stitches (contributing to making the fabric tubular). The back bed knits only from left to right, the second side of the tube. E6000 technique 185 with locks set to N/OX will produce tubular FI with long stitch. For three and four colors where the colors are separated at one row per color use technique 252, locks set to N/OX. Superimposing patterns for three and four color techniques require entering card reader techniques. With my cable set up, when I was experimenting with reader techniques eons ago, I believe I was successful downloading the pattern for the design from the PC, and entering the card reader technique as a second pattern, via the card reader. I have never tried doing so with additional software, and shy away from any situation where I have to enter commands to get the software to work. Out of the group, 162 is the only one that can be combined with a stitch pattern. The console gives cues as to when to change lock settings, with some thought similar fabrics could be knit on the Brother KM. The techniques, and my notes, which at this point would need some self-interpretation. The UX scribble is in reference to a fabric that slips over needles with pushers selected down from right to left, then tucks over needles with pushers selected down from left to right. Needles with pushers up will always knit. In Brotherese the pattern is knit with opposite function cam buttons in use slip <–, tuck –>. It will not produce a tubular knit. Worked out patterns for such fabrics were included in some of the Brother punchcard pattern books.

For tucked 2 colors fair isle use technique 185 with lock set on N/OX.

For tucked 2 colors fair isle use technique 185 with lock set on N/OX.

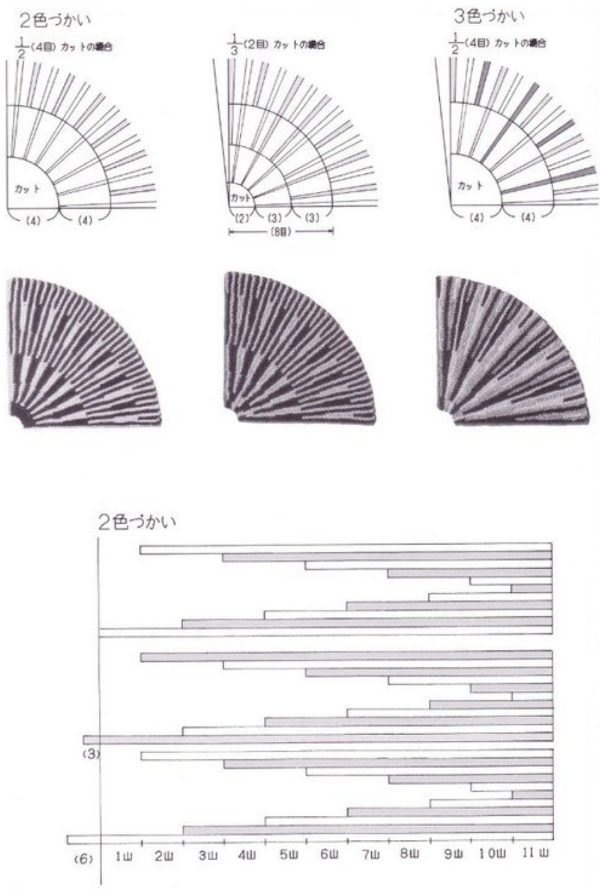

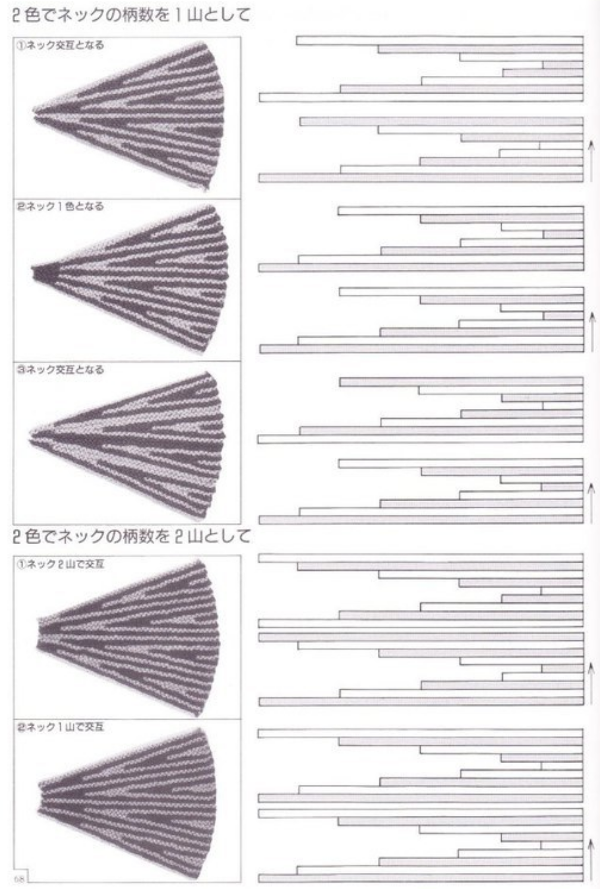

In Method 2/B: the separation occurs in two-row units.

In Method 2/B: the separation occurs in two-row units.

Another former handout, intended for Passap knitters. Many of these fabric options could be emulated on the Brother machine, if separation method 1 were available, with a bit of interpretation. A

Another former handout, intended for Passap knitters. Many of these fabric options could be emulated on the Brother machine, if separation method 1 were available, with a bit of interpretation. A  Automated color separations preparations for download happen easily when using Ayab and img2 track software and accompanying cables. In addition to the familiar built-in KRC separation, there are a variety of other options. For more information please see

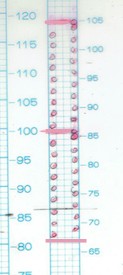

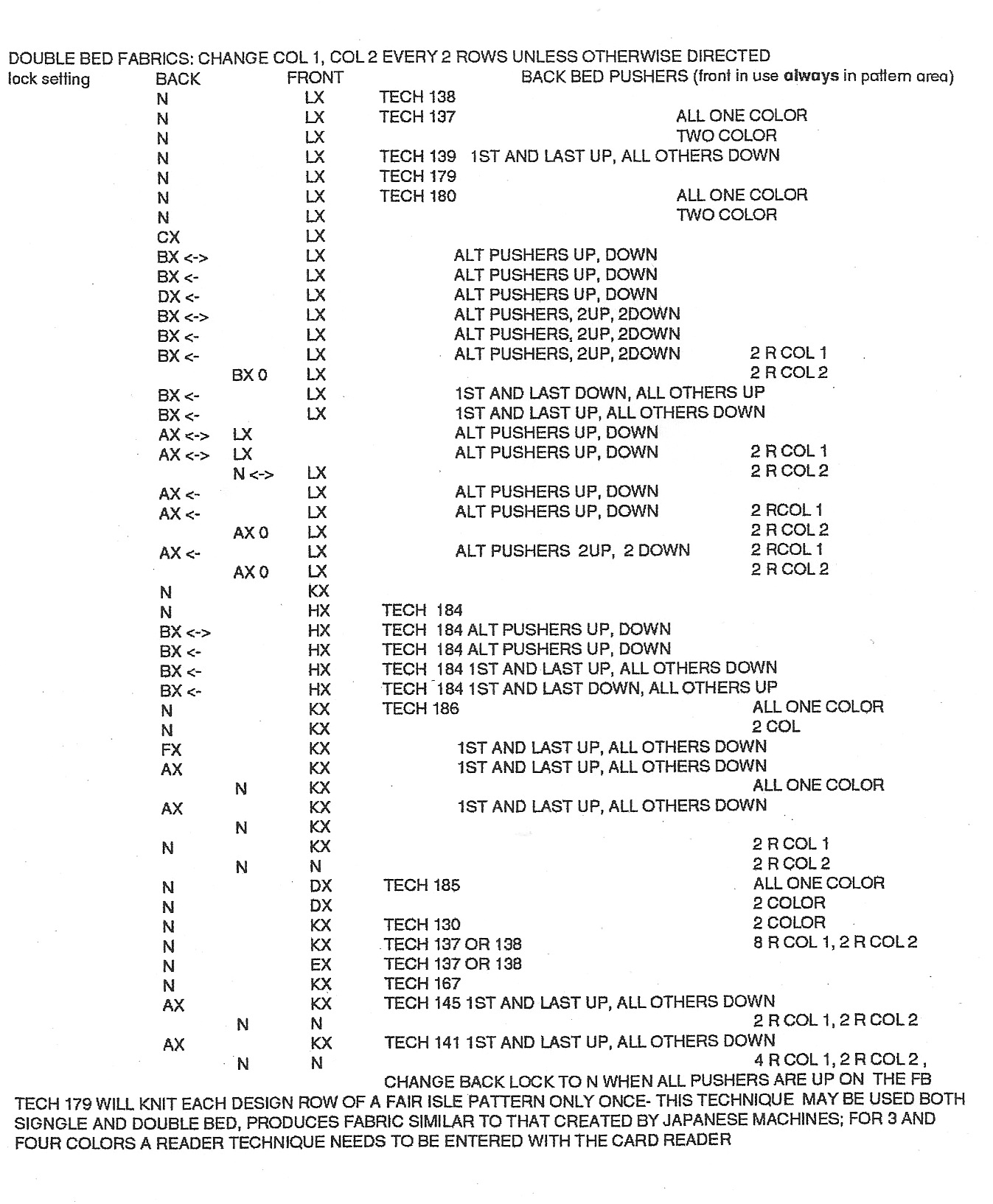

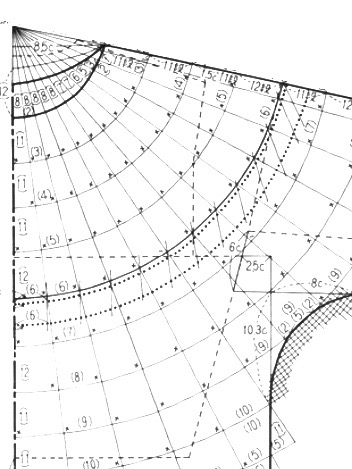

Automated color separations preparations for download happen easily when using Ayab and img2 track software and accompanying cables. In addition to the familiar built-in KRC separation, there are a variety of other options. For more information please see M= Memory: each of the tiny red spots on the garment representations lights up, as specs on motif are entered or reviewed. CE= cancel entry: corrects programmed numbers or cancels the red error light when it flashes. CR= cancel row: press in a number, say 2 on the panel, and the card moves back 2 rows. If you press the button and no number is entered, the error light flashes and the card stops advancing. This is the same as locking the punchcard to repeat a pattern row. RR= row return brings the card back to the set line. This is routinely done before shutting off the machine when knitting is complete or to remove the mylar for editing. CF= card forward. The mylar returns to programmed design row 1. Numbers pressed in using CR or CF do not change those programmed using the M button.

M= Memory: each of the tiny red spots on the garment representations lights up, as specs on motif are entered or reviewed. CE= cancel entry: corrects programmed numbers or cancels the red error light when it flashes. CR= cancel row: press in a number, say 2 on the panel, and the card moves back 2 rows. If you press the button and no number is entered, the error light flashes and the card stops advancing. This is the same as locking the punchcard to repeat a pattern row. RR= row return brings the card back to the set line. This is routinely done before shutting off the machine when knitting is complete or to remove the mylar for editing. CF= card forward. The mylar returns to programmed design row 1. Numbers pressed in using CR or CF do not change those programmed using the M button.

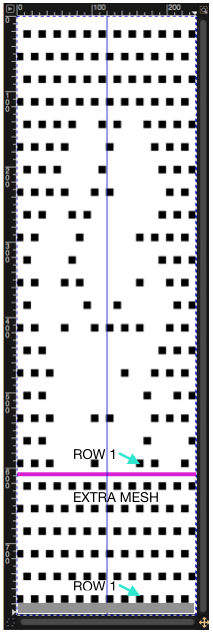

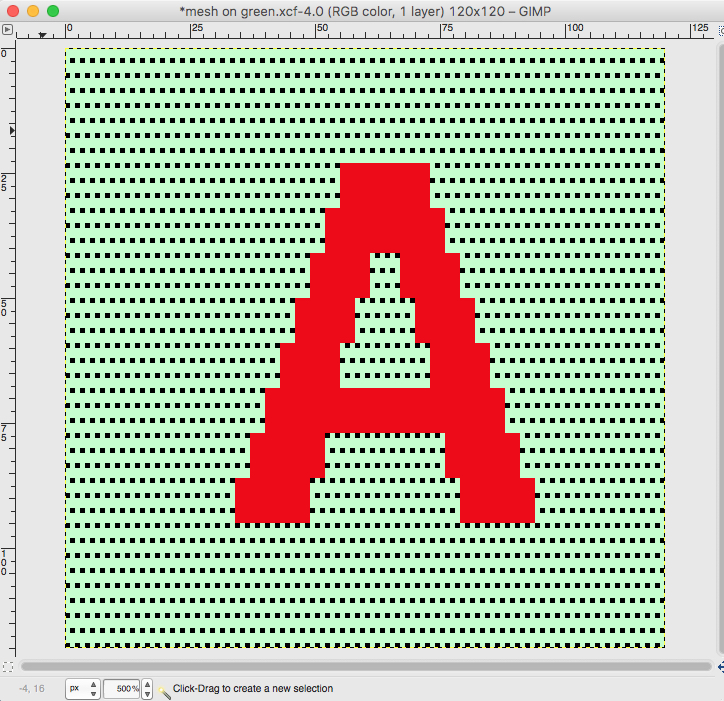

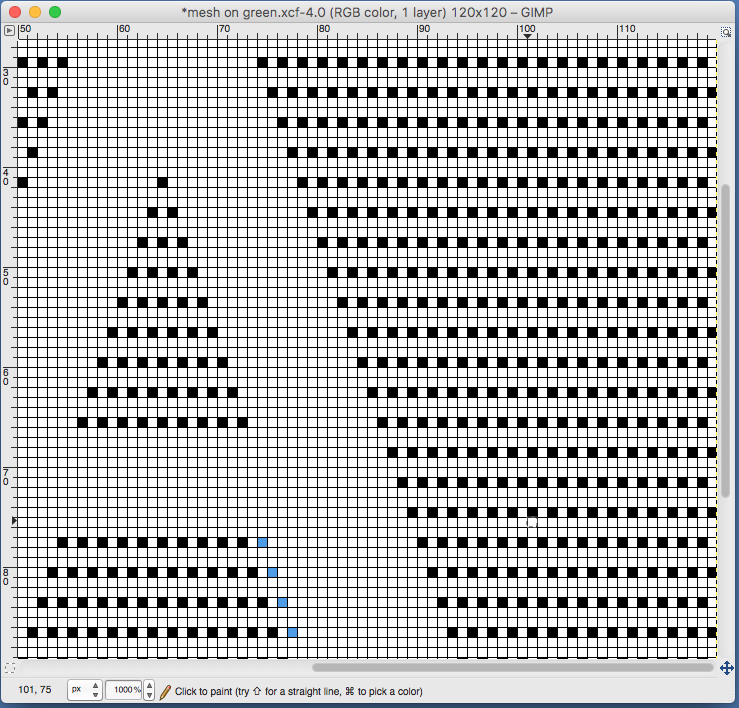

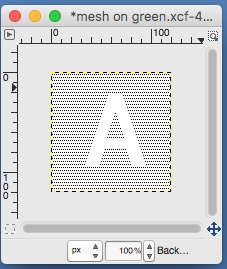

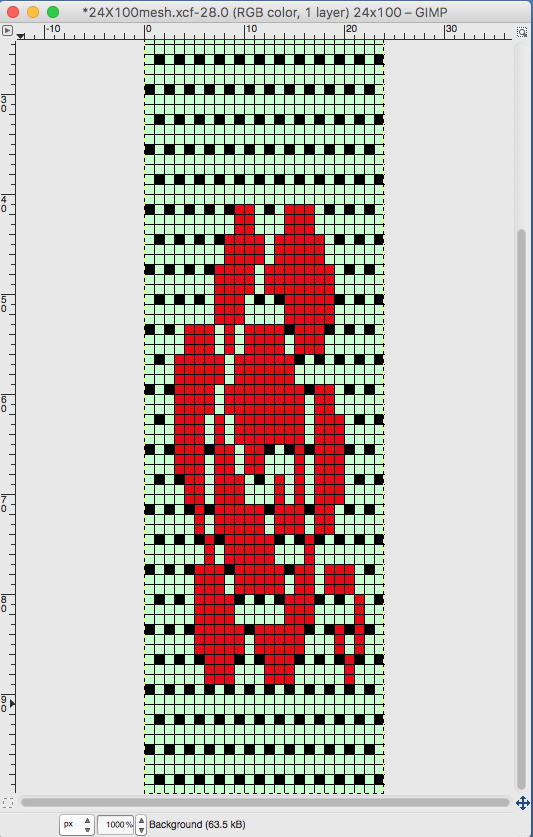

In terms of placement: if the all-over mesh is programmed centered on G1, and the motif is positioned with FNP other than G1, any simple, extra rows of mesh prior to starting the all-over pattern (below green line), will need to be programmed separately with adjustments also in FNP to match the superimposed segment. The programmed repeat for the mesh “rose” below would begin immediately above the blue line, and the extra mesh rows at the top would provide the transition to the start of the rose once again. The height of the pattern seen in the B column in the first illustration may be adjusted accordingly.

In terms of placement: if the all-over mesh is programmed centered on G1, and the motif is positioned with FNP other than G1, any simple, extra rows of mesh prior to starting the all-over pattern (below green line), will need to be programmed separately with adjustments also in FNP to match the superimposed segment. The programmed repeat for the mesh “rose” below would begin immediately above the blue line, and the extra mesh rows at the top would provide the transition to the start of the rose once again. The height of the pattern seen in the B column in the first illustration may be adjusted accordingly.

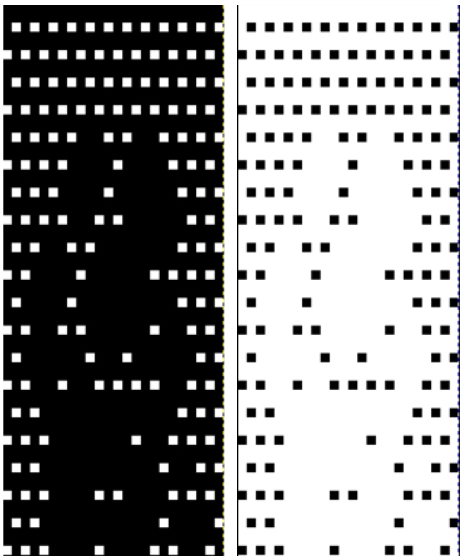

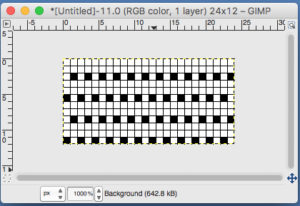

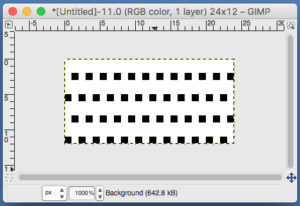

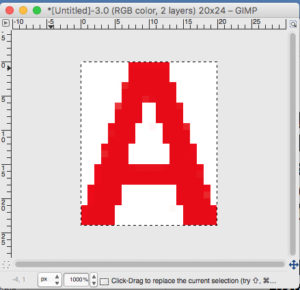

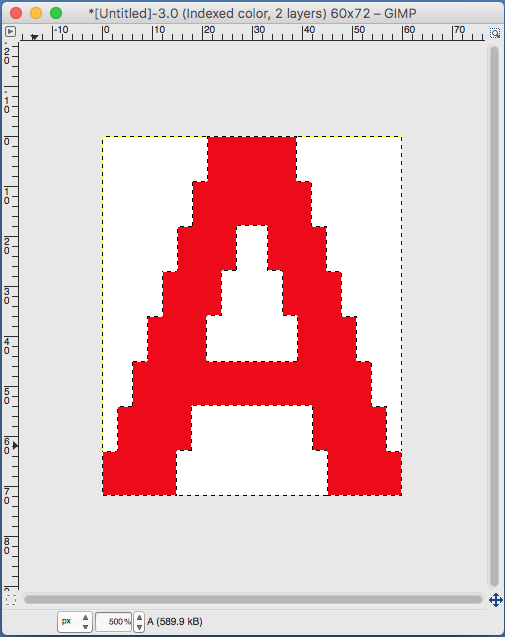

the A pasted in place

the A pasted in place

feeling better, with the exception of the left side bottom of right leg of A

feeling better, with the exception of the left side bottom of right leg of A one last bit of clean up, switching between magnification as needed

one last bit of clean up, switching between magnification as needed

use selection editor or fuzzy select

use selection editor or fuzzy select paste and move to “best” spot

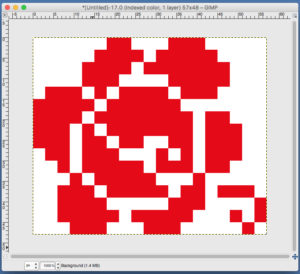

paste and move to “best” spot  not quite a rose

not quite a rose

When satisfied, export in format for download.

When satisfied, export in format for download.

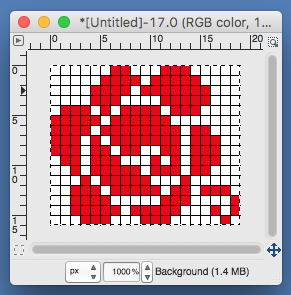

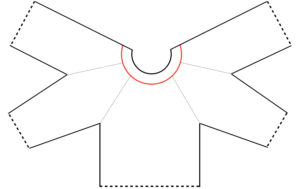

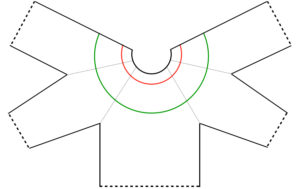

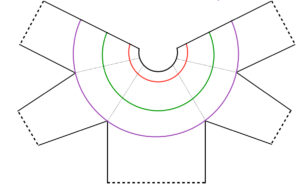

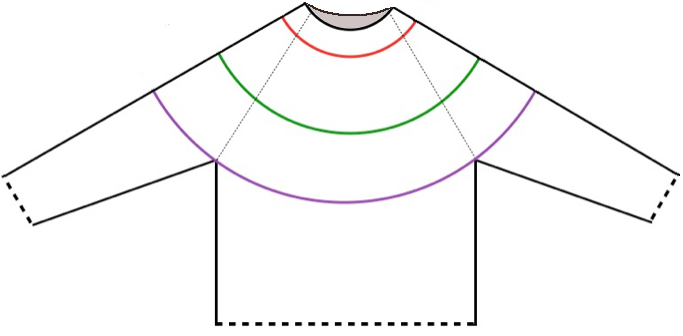

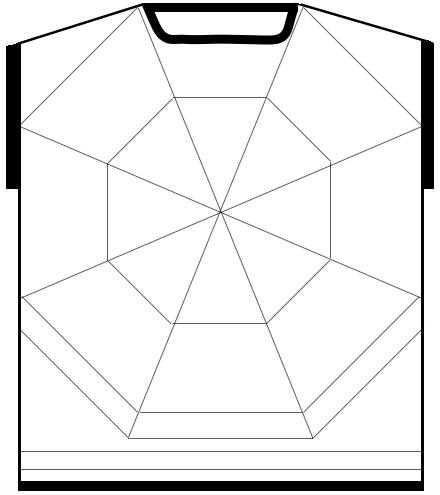

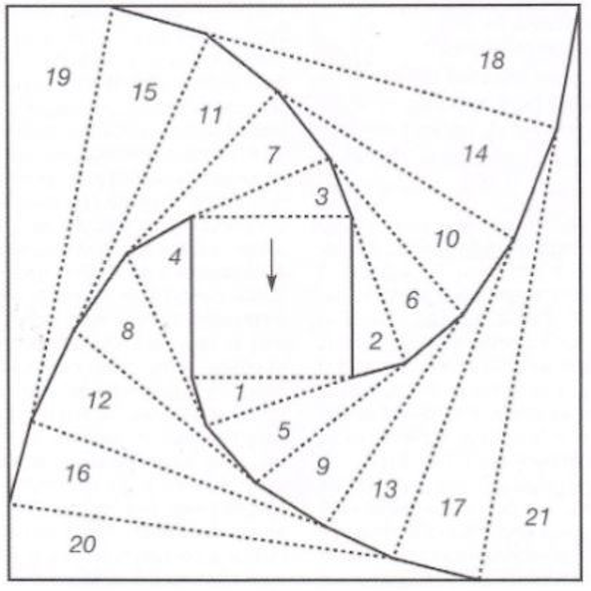

Starting with a square shape and going around.

Starting with a square shape and going around.

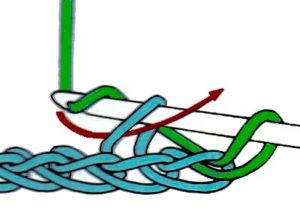

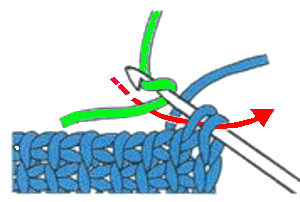

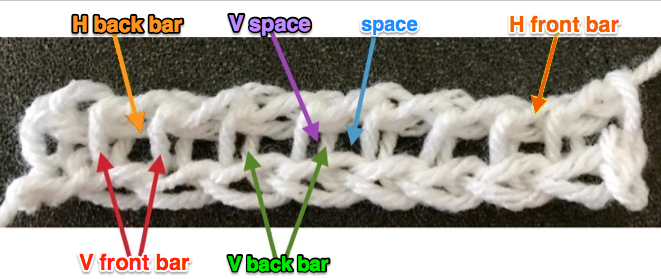

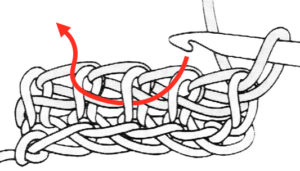

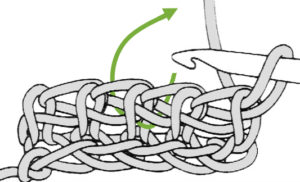

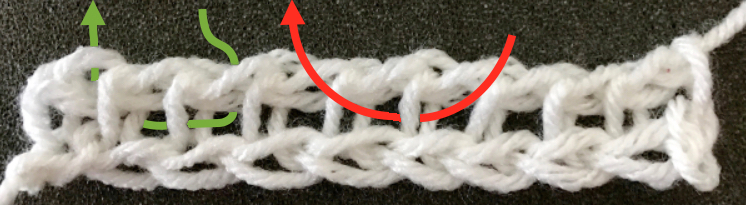

Since I am now involved in a group interested chiefly in crochet, I got curious about executing the fabric in crochet. Part of the problem is that enough texture needs to be created to be able to read the “shadows”. I tried crocheting in different parts of the chain, around the posts in the row below, and ultimately went back to afghan stitch. I had not used the latter since making blankets first for my son, and then for my grandchildren.

Since I am now involved in a group interested chiefly in crochet, I got curious about executing the fabric in crochet. Part of the problem is that enough texture needs to be created to be able to read the “shadows”. I tried crocheting in different parts of the chain, around the posts in the row below, and ultimately went back to afghan stitch. I had not used the latter since making blankets first for my son, and then for my grandchildren.