Decades ago UKI used to offer 92 colors in a 3M elastic, and for some time lots of folks were experimenting with using it as the second color in fair isle. A company now defunct called Impresario used to even sell pattern books for garments using the technique, with the no stretch ground yarns creating ruffled details in cuffs and sleeves. One of my students during that time made a whole collection where the elastic was used in shaping segments of pieces and even in a whole dress. Since pleating, folds, blisters, bubbles have been intermittent themes in my blog posts the elastic and “unusual” fiber use seems to be a natural follow up in my swatch knitting experiments.

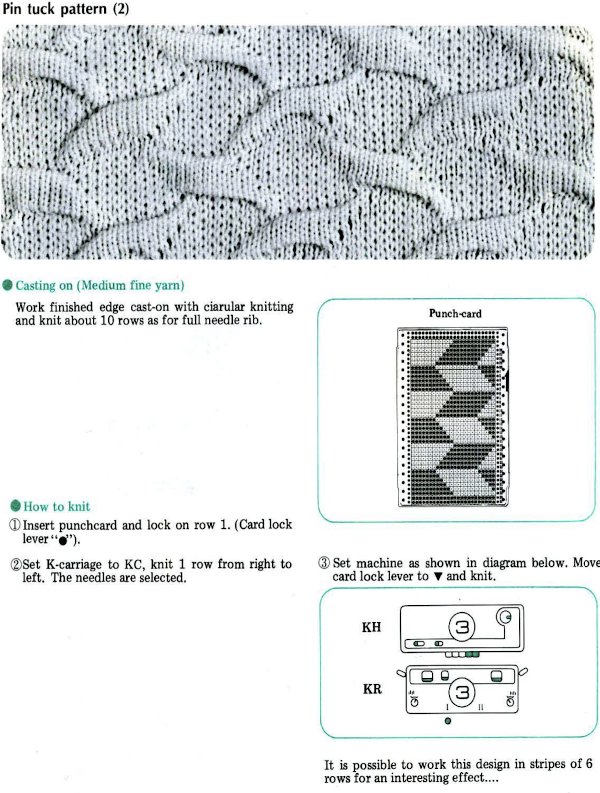

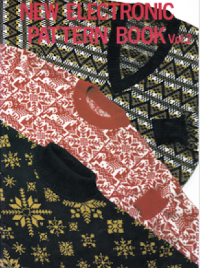

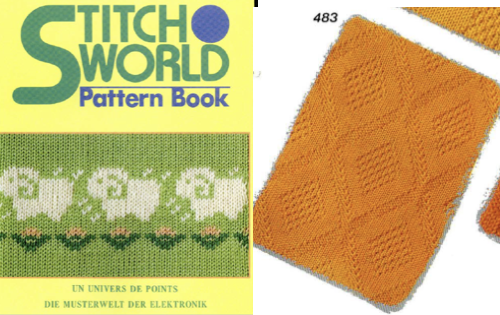

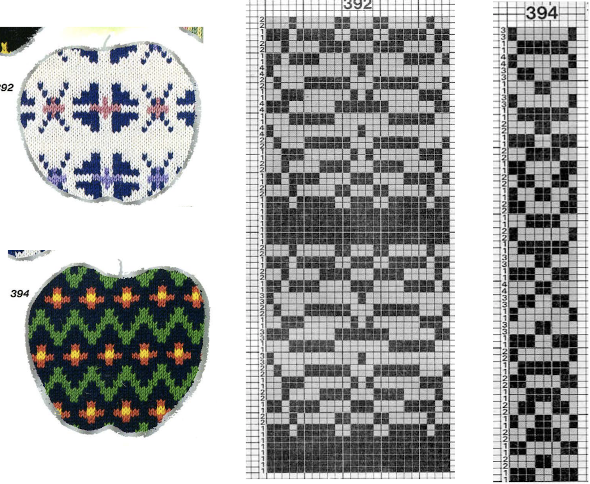

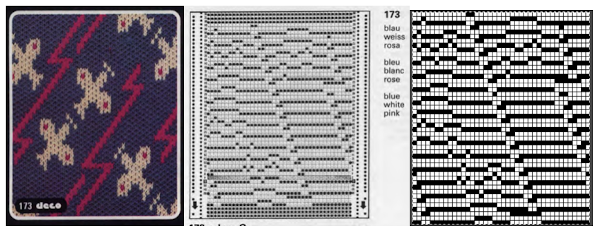

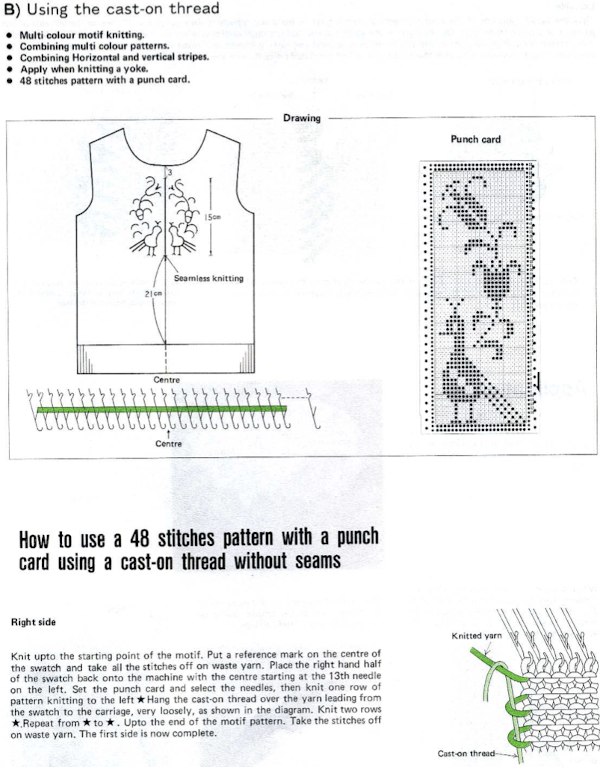

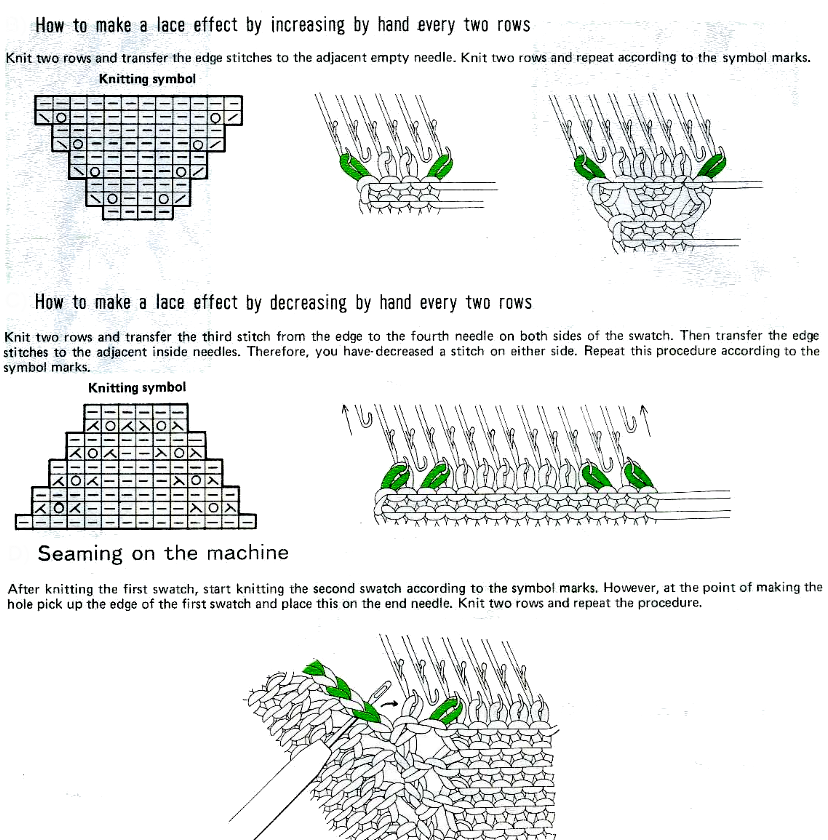

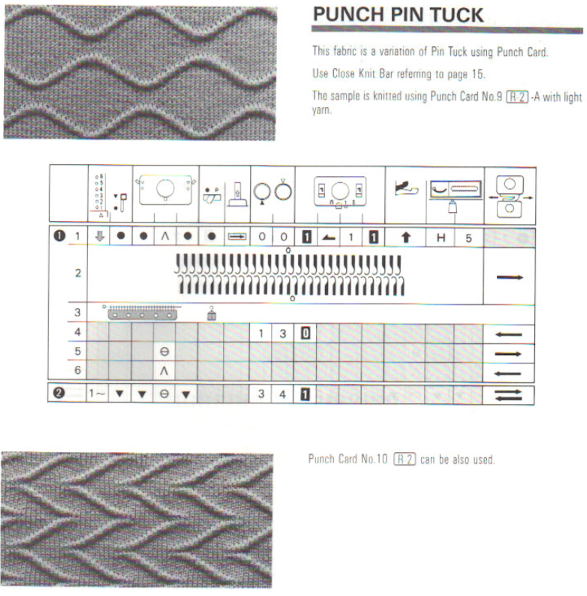

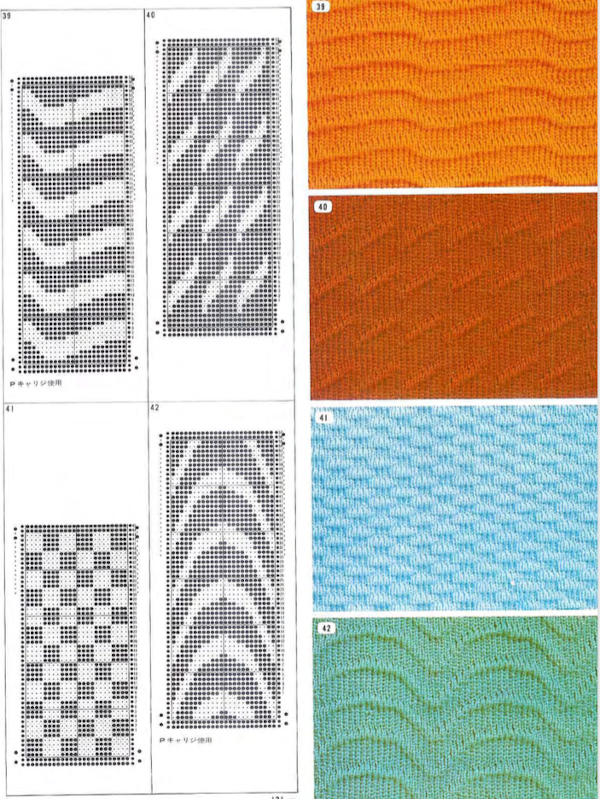

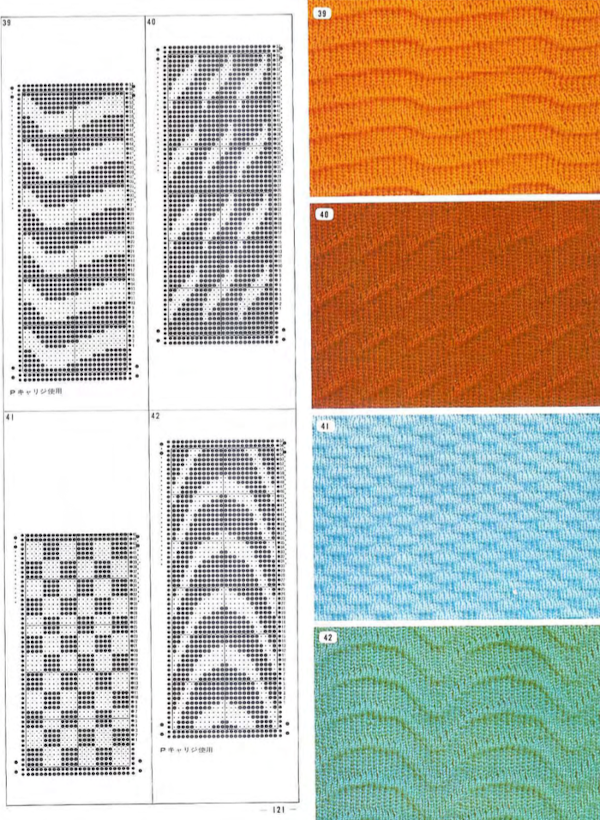

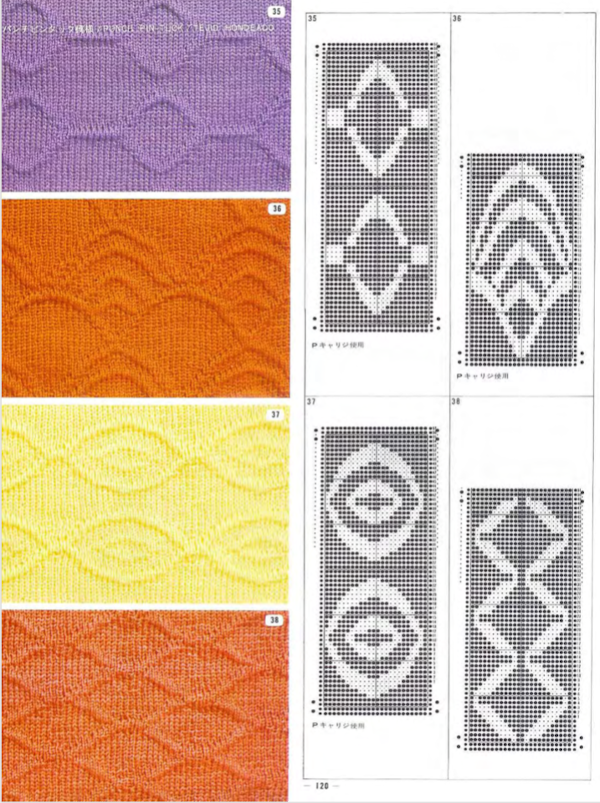

Early published designs can be found using elastic in patterning. Thread lace was an early feature in Silver Reed machines, so if that is a fabric that is attractive, downloading Studio specific punchcard books or those for their electronic designs is well worth it and provides a wealth of inspiration for the related knits. The knitting technique is often referred to as punch lace in early pubs If a clear color contrast is desired, FI is the better option. One such source:

If a clear color contrast is desired, FI is the better option. One such source:

The above patterns are decoded for use on Brother electronics in a subsequent post

The above patterns are decoded for use on Brother electronics in a subsequent post

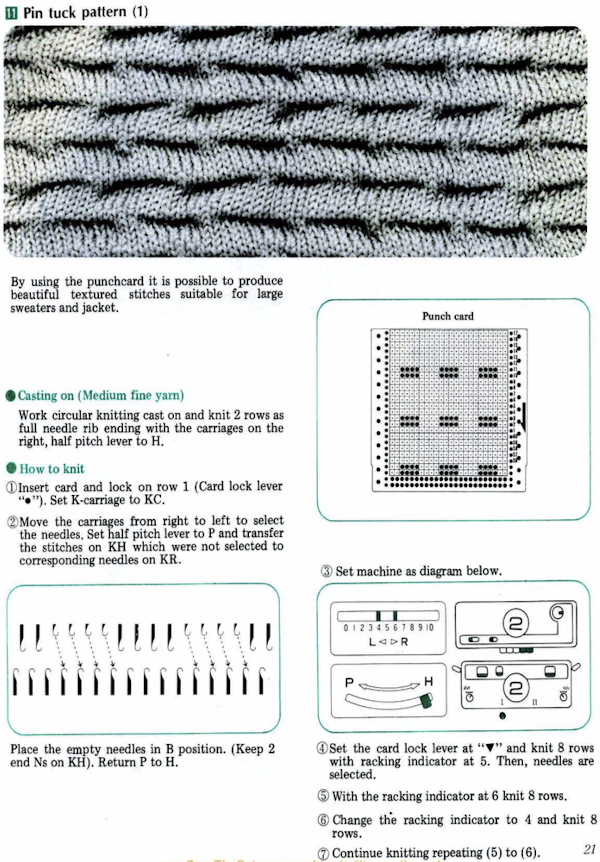

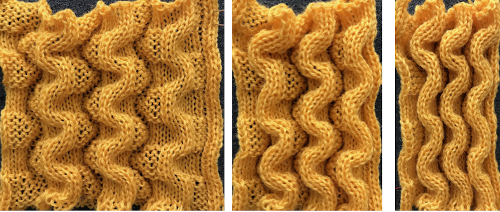

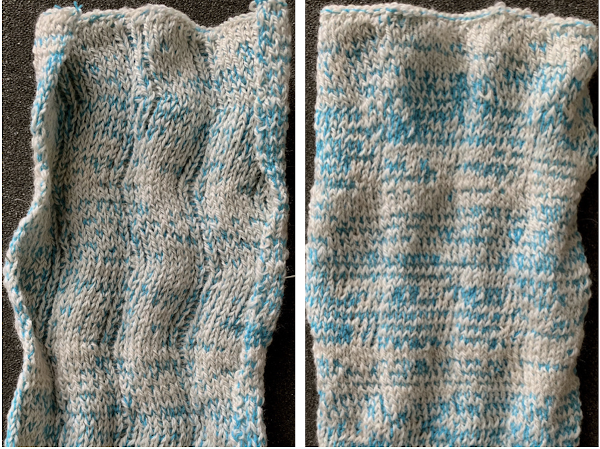

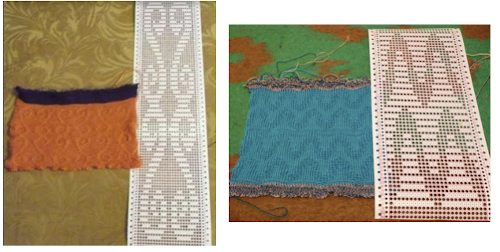

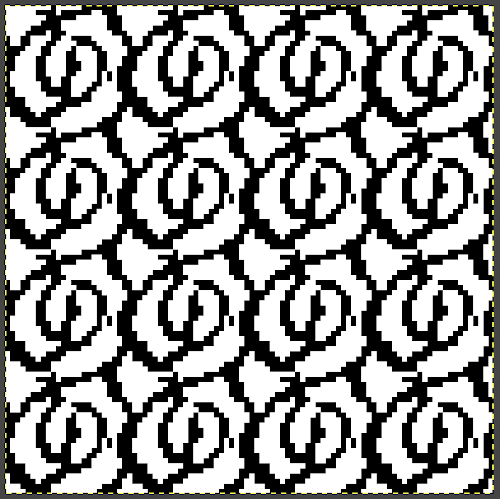

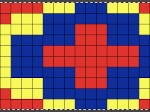

In an earlier post on “pretend cables” I shared a demo swatch from my teaching days (shown sideways) that became the springboard for the mentioned student collection

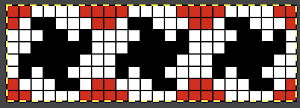

and its accompanying punchcard repeat:

and its accompanying punchcard repeat: UKI is no longer available. I recently acquired some Yeoman elastomeric nylon-lycra yarn. The latter is supplied on 1450 yards per pound cones in 23 colors.

UKI is no longer available. I recently acquired some Yeoman elastomeric nylon-lycra yarn. The latter is supplied on 1450 yards per pound cones in 23 colors.

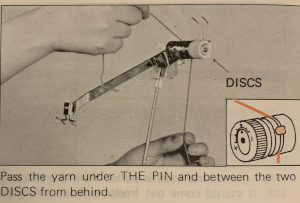

There were several things to be sorted out for the elastic to feed smoothly. The first was to separate it into more than one cone with the intent of using at least 2 strands since one did not seem to work predictably. After trying a variety of trial methods including bypassing the tension dial in the yarn mast, ultimately the best results were obtained by threading the elastic as any other yarn but taping the metal disks spaced apart in the assembly thus reducing the pressure and upper tension on the elastic as it advanced through the mast for knitting.

The normal threading

Here the white yarn shows position beneath the pin

Here the white yarn shows position beneath the pin  and scotch tape in place to adjust the amount of pressure exerted on the elastic.

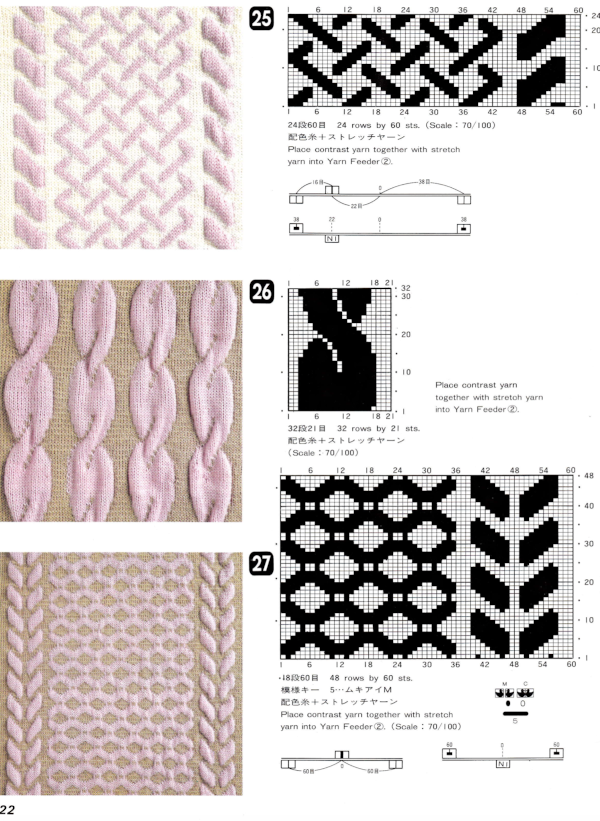

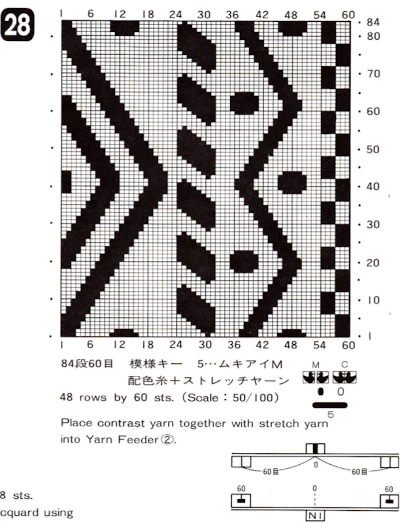

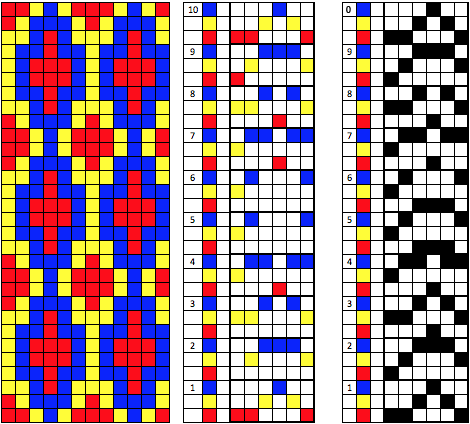

and scotch tape in place to adjust the amount of pressure exerted on the elastic.  As a matter of routine, even if the goal is to knit the fibers double bed, it is always best to make certain one gets familiar with yarn feeding, tensions, changes when larger widths of knitting are attempted, etc. on the single bed. The first tests were knit using the fair isle and thread lace settings single bed. Though I am using img2track to download to a 930, I do not have a 930 carriage (910 ones do not have a thread lace option), so I worked the swatches using a punchcard model carriage. The repeats used were planned to include borders on each side to ensure those stitches would knit in the second, B feeder color in fair isle (black squares, punched holes), or together in white squares (unpunched holes) in thread lace. Fair Isle produces a double set of floats on the purl side.

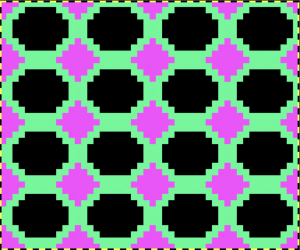

As a matter of routine, even if the goal is to knit the fibers double bed, it is always best to make certain one gets familiar with yarn feeding, tensions, changes when larger widths of knitting are attempted, etc. on the single bed. The first tests were knit using the fair isle and thread lace settings single bed. Though I am using img2track to download to a 930, I do not have a 930 carriage (910 ones do not have a thread lace option), so I worked the swatches using a punchcard model carriage. The repeats used were planned to include borders on each side to ensure those stitches would knit in the second, B feeder color in fair isle (black squares, punched holes), or together in white squares (unpunched holes) in thread lace. Fair Isle produces a double set of floats on the purl side. ![]()

Thread lace produces a single set of floats (in this case the elastic), the white border is not visible in the repeat below, it is the same as the above fabric, with colors reversed. I prefer the single float backing. In addition, for these fabrics the elastic is placed in the A feeder, the yarn in B

Thread lace produces a single set of floats (in this case the elastic), the white border is not visible in the repeat below, it is the same as the above fabric, with colors reversed. I prefer the single float backing. In addition, for these fabrics the elastic is placed in the A feeder, the yarn in B![]()

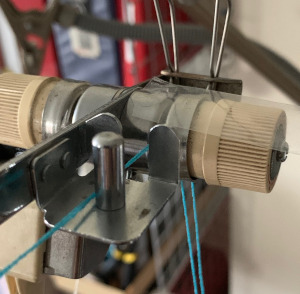

I found the standard sinker plate kept having issues with the thread lace option, getting needles caught up in it as it attempted to move across the bed. The sinker plate that was provided with the punchcard machine was actually different, and when I switched to using it I had no further problems. Arrows point to differences, I have long since replaced all brushes with wheels on all my sinker plates. Be aware when purchasing any of them that the bulky KM ones are slightly larger.

I found the standard sinker plate kept having issues with the thread lace option, getting needles caught up in it as it attempted to move across the bed. The sinker plate that was provided with the punchcard machine was actually different, and when I switched to using it I had no further problems. Arrows point to differences, I have long since replaced all brushes with wheels on all my sinker plates. Be aware when purchasing any of them that the bulky KM ones are slightly larger.  A second thread lace variation:

A second thread lace variation:

![]()

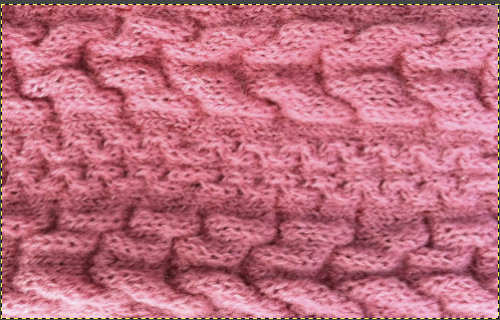

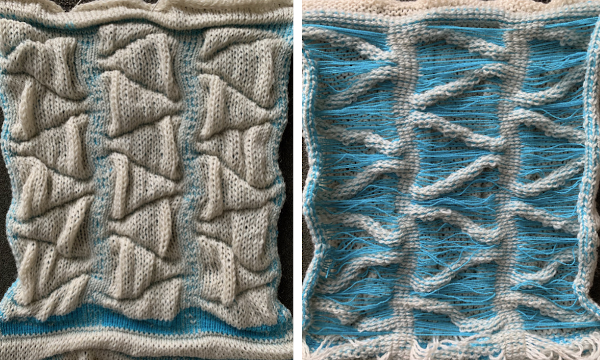

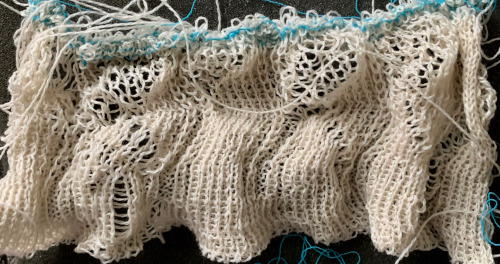

The multiple folds and creases, as opposed to smooth blister in all the above, are very interesting to me.

The multiple folds and creases, as opposed to smooth blister in all the above, are very interesting to me.

There are many scientific papers being written on 3D knitting that explore pleating achieved by using knit and purl combinations which to some degree could be emulated on home knitting machines equipped with a G carriage. Other work explores properties achieved by using elastics in the mix, they can be found by searching for “axometric knits”.

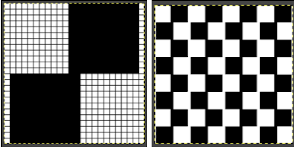

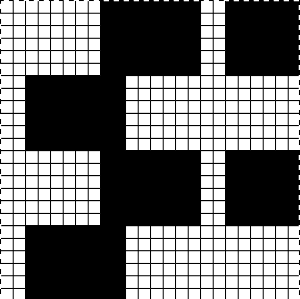

Many interesting pleating effects may be achieved by using knit and purl combinations. Unless one has a mechanical aid such as a Gcarriage transferring between beds can be tedious and hard to do correctly for lengthy pieces of knitting. I illustrated one sample in the post  I decided to now test a similar block structure using the thread lace setting, first with a large check and then a far smaller one

I decided to now test a similar block structure using the thread lace setting, first with a large check and then a far smaller one

The spots, where the elastic and yarn knit together, are compressed, so the results are quite different than what might be expected from studying the chart

The spots, where the elastic and yarn knit together, are compressed, so the results are quite different than what might be expected from studying the chart  A quick, imperfect sample using a fine cotton and a single strand of the elastic, each with its own upper tension disk adjustments.

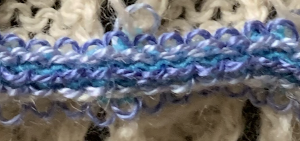

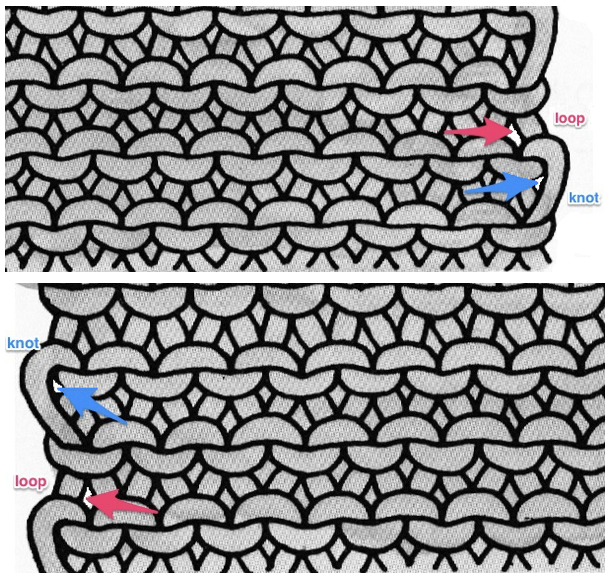

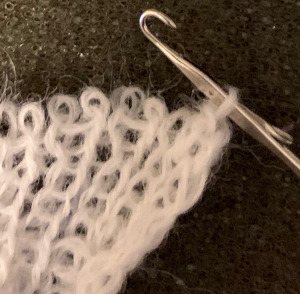

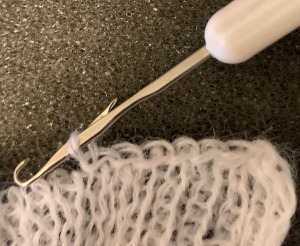

A quick, imperfect sample using a fine cotton and a single strand of the elastic, each with its own upper tension disk adjustments. a close-up of the elastic and cotton, though they are knitting stocking stitch together, the cotton does not have the same stretch factor, so the loop formation as viewed on the purl side is different

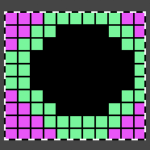

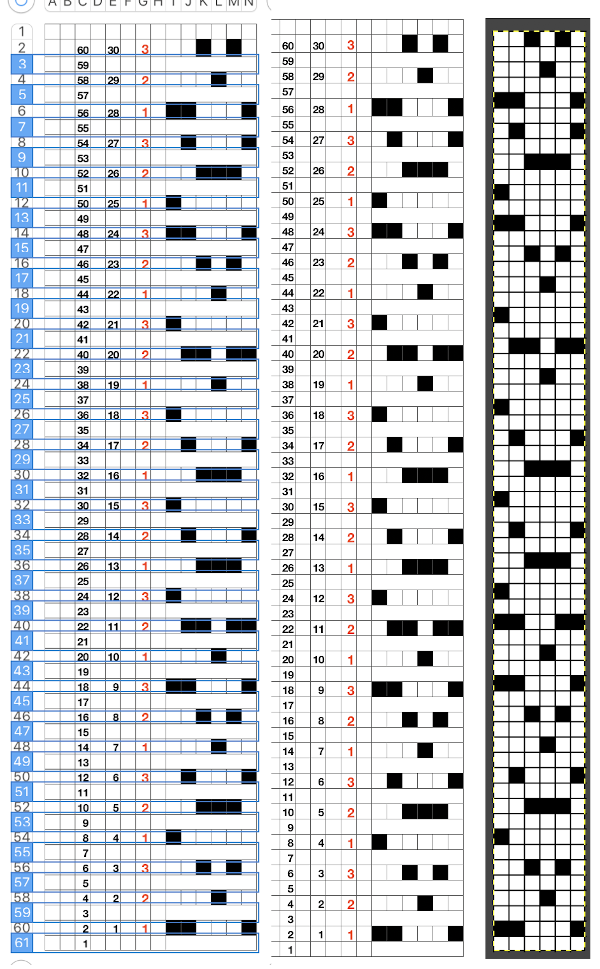

a close-up of the elastic and cotton, though they are knitting stocking stitch together, the cotton does not have the same stretch factor, so the loop formation as viewed on the purl side is different What of knitting on a double bed? An axometric shape, a tentative repeat worked out and in turn elongated X2 and tiled to check alignment.

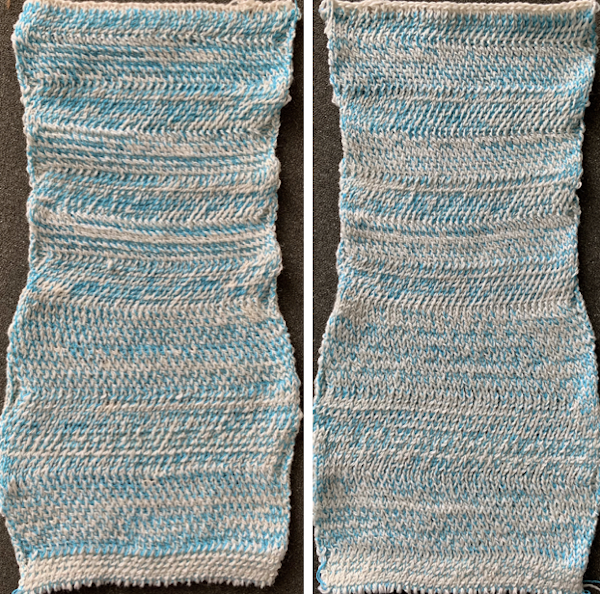

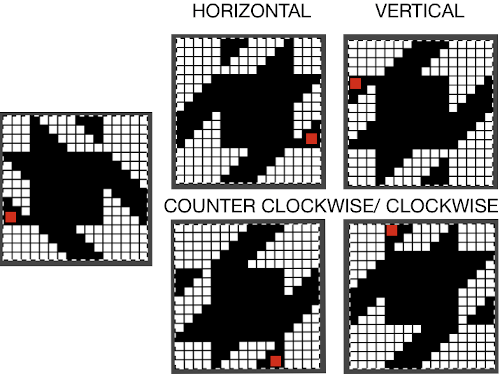

What of knitting on a double bed? An axometric shape, a tentative repeat worked out and in turn elongated X2 and tiled to check alignment.  The original repeat is composed of an odd number of rows in height. Usually, double bed knitting relying on color changes or automatic DBJ KRC separations require an even number of rows in the motif. The first sample was executed using single-ply cotton and elastic yarns respectively, fed through separate upper tension disks but knit together as a single color. The swatch is 72 stitches in width but measures only 14.5 mm (5.7 inches) in width, producing a gauge of nearly 13 stitches for inch, not achievable when knitting with standard fibers on a standard 4.5 mm machine. The pattern is subtle, more visible on the knit side, hard to tell there are pockets in the knit. The cotton is space-dyed, and as true when using such yarns, that causes some confusion in immediately identifying a clear pattern. The ruffled effect is simply from a plain knit start and color-changing stripes to test tension and knittability on the planned needle width. Machine settings: opposite part buttons, no lili

The original repeat is composed of an odd number of rows in height. Usually, double bed knitting relying on color changes or automatic DBJ KRC separations require an even number of rows in the motif. The first sample was executed using single-ply cotton and elastic yarns respectively, fed through separate upper tension disks but knit together as a single color. The swatch is 72 stitches in width but measures only 14.5 mm (5.7 inches) in width, producing a gauge of nearly 13 stitches for inch, not achievable when knitting with standard fibers on a standard 4.5 mm machine. The pattern is subtle, more visible on the knit side, hard to tell there are pockets in the knit. The cotton is space-dyed, and as true when using such yarns, that causes some confusion in immediately identifying a clear pattern. The ruffled effect is simply from a plain knit start and color-changing stripes to test tension and knittability on the planned needle width. Machine settings: opposite part buttons, no lili

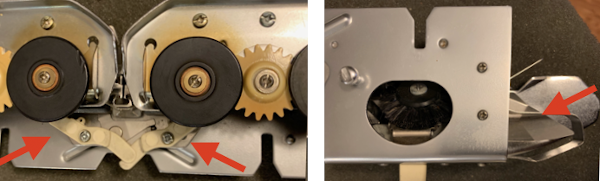

Here the same pattern was executed on the same number of stitches with the white wool used above, but the elastic was plied with a 2/24 acrylic yarn and knit as DBJ with the blue, stretchy combination creating the solid color backing

Here the same pattern was executed on the same number of stitches with the white wool used above, but the elastic was plied with a 2/24 acrylic yarn and knit as DBJ with the blue, stretchy combination creating the solid color backing  a comparison in scale

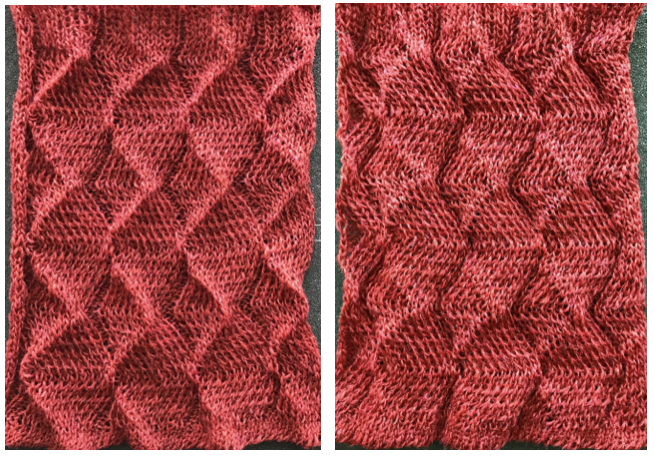

a comparison in scale  My future intent is to try for some of the 3D shapes obtained with racking, but prior to that, I tested the yarn and tensions on some simple every needle rib racked patterns. Because of the movement required across the metal bed for racking to occur, I chose to continue using the same wool as above, rather than thin cotton likely to break from the stress of those movements. A plating feeder would do a better job of distributing the colors, which here become muddied as seen any time 2 contrasting colors are knit together and are used as “one strand”. Racking every 2 rows (swatch bottom) will stress the yarn less than every one row (swatch top). The knitting was fairly easy at tension 4 and 3 respectively. Both carriages were set to knit in both directions. The weighted rib on the machine measured 16 inches, 10 when off it and relaxed. The width nearly doubles when fully stretched.

My future intent is to try for some of the 3D shapes obtained with racking, but prior to that, I tested the yarn and tensions on some simple every needle rib racked patterns. Because of the movement required across the metal bed for racking to occur, I chose to continue using the same wool as above, rather than thin cotton likely to break from the stress of those movements. A plating feeder would do a better job of distributing the colors, which here become muddied as seen any time 2 contrasting colors are knit together and are used as “one strand”. Racking every 2 rows (swatch bottom) will stress the yarn less than every one row (swatch top). The knitting was fairly easy at tension 4 and 3 respectively. Both carriages were set to knit in both directions. The weighted rib on the machine measured 16 inches, 10 when off it and relaxed. The width nearly doubles when fully stretched.  I was curious to try a pattern previously tested in an all wool

I was curious to try a pattern previously tested in an all wool

The stitches were quite compressed, the color mixing makes the shapes harder to trace, the fabric measures nearly double in width when fully stretched in width, the needle arrangement is more visible at that point.

The stitches were quite compressed, the color mixing makes the shapes harder to trace, the fabric measures nearly double in width when fully stretched in width, the needle arrangement is more visible at that point. The needle arrangement was changed. The finished swatch measured 24 inches when weighted and on the machine, approximately 18 inches when off and relaxed. The maximum width was expanded from 4 to 12 inches

The needle arrangement was changed. The finished swatch measured 24 inches when weighted and on the machine, approximately 18 inches when off and relaxed. The maximum width was expanded from 4 to 12 inches  The “pleating” arrangement is noticeable in this view

The “pleating” arrangement is noticeable in this view![]()

Working with a similar arrangement I decided to try having patterning on the top bed, with the aim to tuck on the single needles in work in the repeat (bottom line of black squares). Not all ideas are an immediate success. Wanting to see the effect on the single-ply wool I began with that at the tension that appeared to be required for knitting it along with the elastic and stitches were far too loose.

Working with a similar arrangement I decided to try having patterning on the top bed, with the aim to tuck on the single needles in work in the repeat (bottom line of black squares). Not all ideas are an immediate success. Wanting to see the effect on the single-ply wool I began with that at the tension that appeared to be required for knitting it along with the elastic and stitches were far too loose. I had more success and a bit better definition of the fabric by knitting with both strands together from the bottom up. In an effort to attempt to have better color distribution I used the plating feeder and had some issues with stitches not knitting off properly. The result was not significantly different than that obtained by simply feeding both yarns together. When using plating feeders both on the single and the double beds one of the yarns may have a tendency to jump out, to prevent that from happening here is one “hack”.

I had more success and a bit better definition of the fabric by knitting with both strands together from the bottom up. In an effort to attempt to have better color distribution I used the plating feeder and had some issues with stitches not knitting off properly. The result was not significantly different than that obtained by simply feeding both yarns together. When using plating feeders both on the single and the double beds one of the yarns may have a tendency to jump out, to prevent that from happening here is one “hack”.

The tuck stitches do help with the definition of the shapes, as do the dropped stitches, a fact worth keeping in mind with a return to pleats and their formation, but likely in another post. Likely the last test in this series, I attempted a version of dragon scales at first using a yarn I knew would be too thin for the effect alone, then added the elastic. The combined yarns did not tolerate tuck and racking combined, so I then used slip stitch <– –>. The yarn alone sample was too loose and thus nearly flat and when the elastic was added the resulting knit became compressed and lost any semblance of 3D

The tuck stitches do help with the definition of the shapes, as do the dropped stitches, a fact worth keeping in mind with a return to pleats and their formation, but likely in another post. Likely the last test in this series, I attempted a version of dragon scales at first using a yarn I knew would be too thin for the effect alone, then added the elastic. The combined yarns did not tolerate tuck and racking combined, so I then used slip stitch <– –>. The yarn alone sample was too loose and thus nearly flat and when the elastic was added the resulting knit became compressed and lost any semblance of 3D The same yarn as above, also knit in tuck setting, showing the difference in size and dimension between slip setting on left, tuck on right

The same yarn as above, also knit in tuck setting, showing the difference in size and dimension between slip setting on left, tuck on right  As with any knitting, keeping an eye on what your yarn is doing still matters. Such as this will lead to a series of circumstances that may bring your project to a far earlier end than planned ;-(

As with any knitting, keeping an eye on what your yarn is doing still matters. Such as this will lead to a series of circumstances that may bring your project to a far earlier end than planned ;-(

A very last effort at attempting the scales with elastic and wool knit at a far looser tension that in previous tests, ended when elastic broke as a result of above, IMO an unremarkable fabric

A very last effort at attempting the scales with elastic and wool knit at a far looser tension that in previous tests, ended when elastic broke as a result of above, IMO an unremarkable fabric  For more swatches and information see post on knitting with elastic 2

For more swatches and information see post on knitting with elastic 2

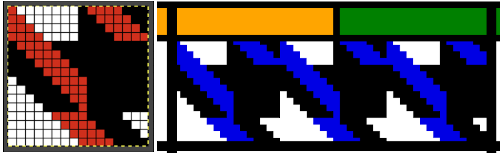

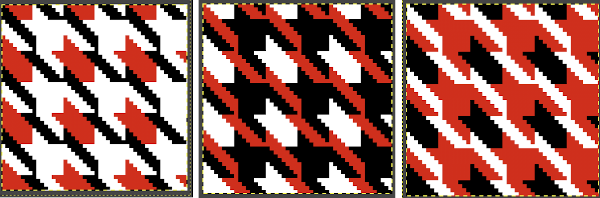

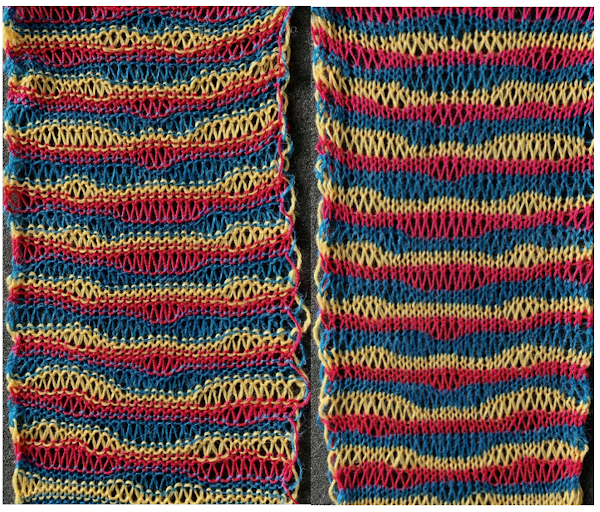

The FI results are shown on the left, the first dbj test with lili buttons engaged and both carriages set to slip in both directions appear to the right. Note the difference in width and height of the resulting knit. The floats in FI are overlong, and there are some separation and lengthening of the stitches along the diagonal edges of the houndstooth shape

The FI results are shown on the left, the first dbj test with lili buttons engaged and both carriages set to slip in both directions appear to the right. Note the difference in width and height of the resulting knit. The floats in FI are overlong, and there are some separation and lengthening of the stitches along the diagonal edges of the houndstooth shape

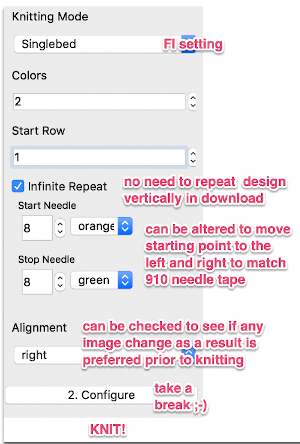

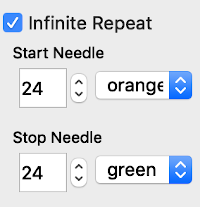

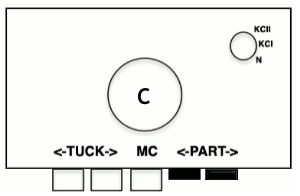

The program does provide prompts as to which color should be picked up next, and clues as to where one is in the repeat, they are found at the bottom of the Ayab window. I happened to grab content with color B upcoming both times.

The program does provide prompts as to which color should be picked up next, and clues as to where one is in the repeat, they are found at the bottom of the Ayab window. I happened to grab content with color B upcoming both times.

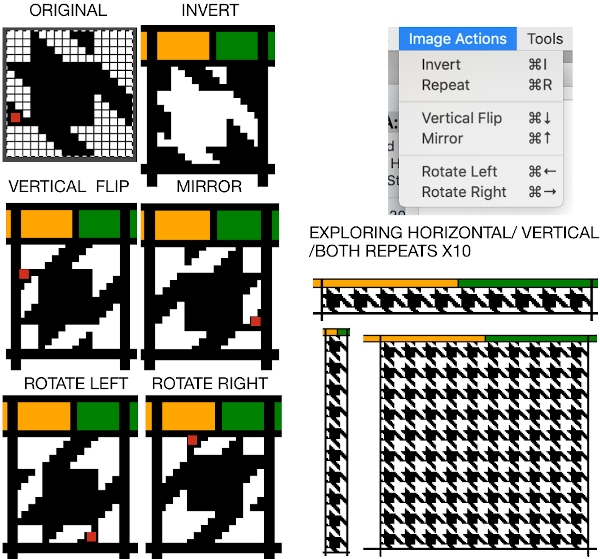

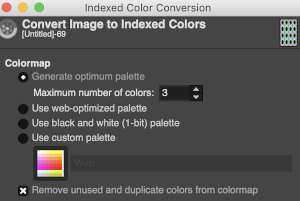

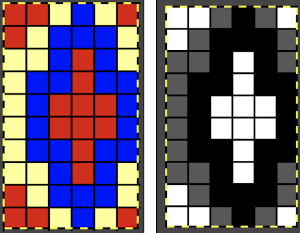

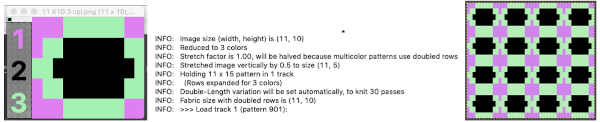

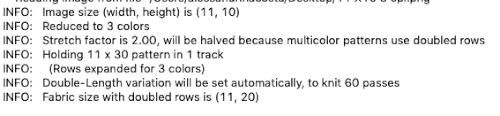

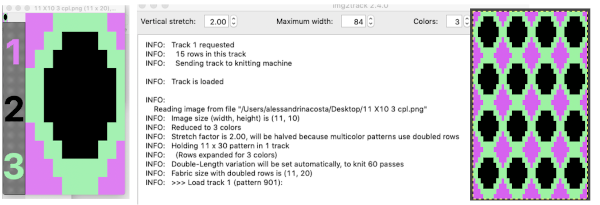

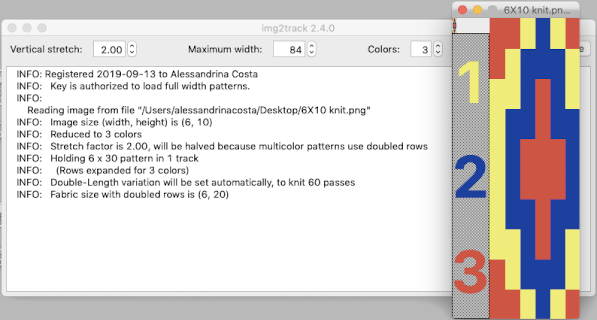

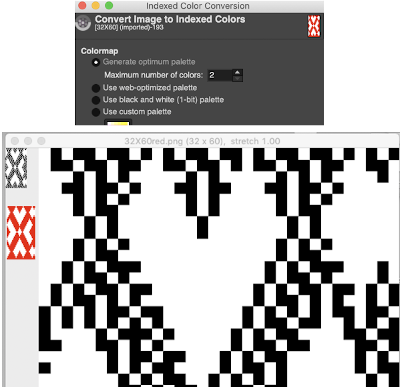

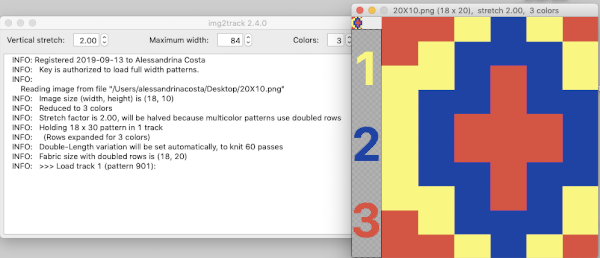

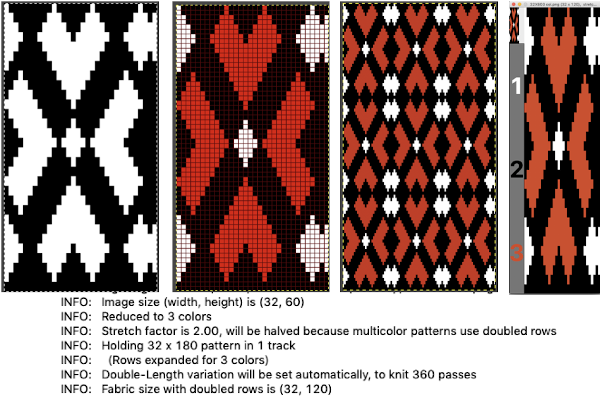

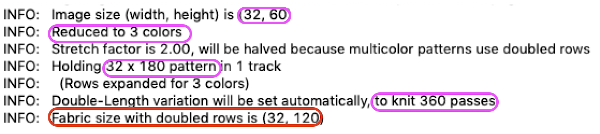

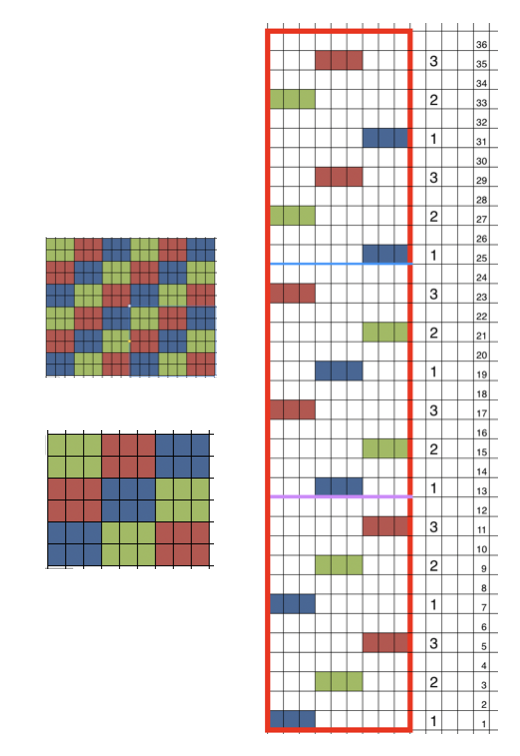

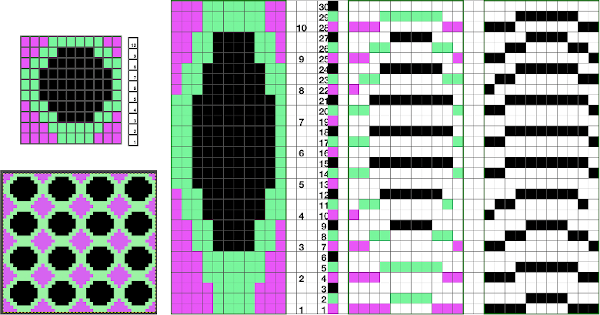

When preparing images for download, they should be indexed to 3 colors

When preparing images for download, they should be indexed to 3 colors

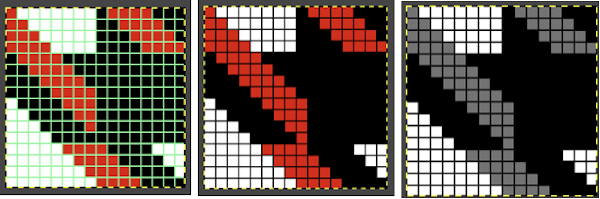

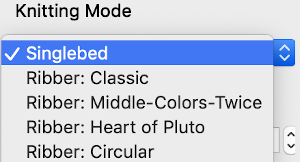

It takes a while when knitting double bed knits before one can assess whether the results are correct in terms of patterning since the knit is hidden for some length as it drops between the beds. Because the Ayab prompts for color changes were altered sometimes when the carriage on the right, sometimes on the left, I dropped the first sample off after slightly more than one repeat, found its patterning to be correct, and that the prompts when on the color changer side for the following row to be knit from left to right were reliable, as shown in the knit swatches. In turn, I used an indexed greyscale image. The lettering on the right indicates where colors were placed following the give instructions, rather than where they were assigned in the original design. The manual states that the color sequence for the separation is: white, grey, black, gray, however, if the prompts for changing colors as given are followed, which is very valuable in tracking them, the knitting occurs in reverse order.

It takes a while when knitting double bed knits before one can assess whether the results are correct in terms of patterning since the knit is hidden for some length as it drops between the beds. Because the Ayab prompts for color changes were altered sometimes when the carriage on the right, sometimes on the left, I dropped the first sample off after slightly more than one repeat, found its patterning to be correct, and that the prompts when on the color changer side for the following row to be knit from left to right were reliable, as shown in the knit swatches. In turn, I used an indexed greyscale image. The lettering on the right indicates where colors were placed following the give instructions, rather than where they were assigned in the original design. The manual states that the color sequence for the separation is: white, grey, black, gray, however, if the prompts for changing colors as given are followed, which is very valuable in tracking them, the knitting occurs in reverse order.  Knitting mode options for DBJ are listed below the single bed one,

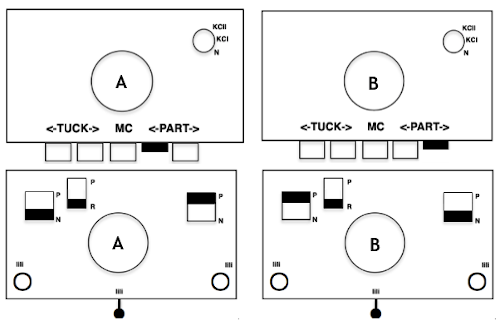

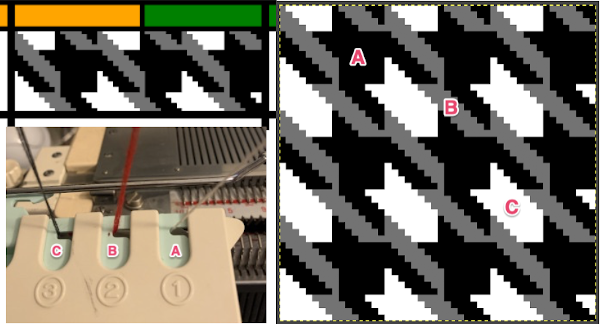

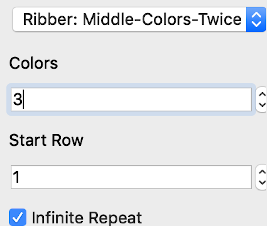

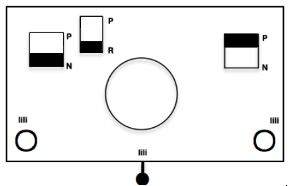

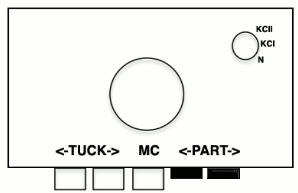

Knitting mode options for DBJ are listed below the single bed one,  The main bed is set to slip in both directions, the ribber as well, with lili buttons engaged. The number of colors is not altered automatically by Ayab, the change needs to be made manually.

The main bed is set to slip in both directions, the ribber as well, with lili buttons engaged. The number of colors is not altered automatically by Ayab, the change needs to be made manually.

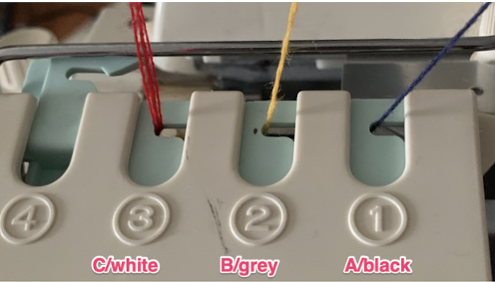

This was the set up in the color changer

This was the set up in the color changer

Planned possible use of the middle color twice may be seen in this image

Planned possible use of the middle color twice may be seen in this image

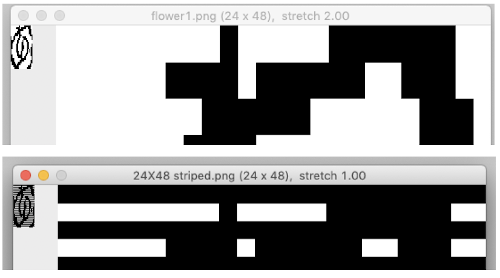

The “striped” repeat produces essentially the same fabric. The knit carriage may be set to slip in both directions when using it since the row of all punched holes or black pixels will knit every stitch on every needle selected while in the previous samples the cam button set to knit in one direction performed that function regardless of any markings on the design repeat. The ribber is set to knit in one direction, slip in the other. Reversing sides for cam button settings produces the same fabric

The “striped” repeat produces essentially the same fabric. The knit carriage may be set to slip in both directions when using it since the row of all punched holes or black pixels will knit every stitch on every needle selected while in the previous samples the cam button set to knit in one direction performed that function regardless of any markings on the design repeat. The ribber is set to knit in one direction, slip in the other. Reversing sides for cam button settings produces the same fabric

The

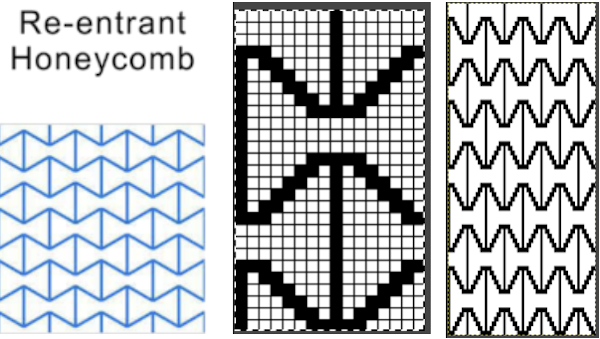

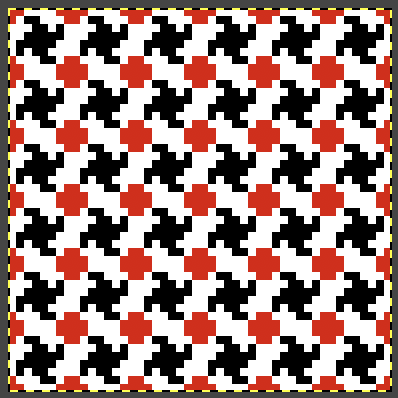

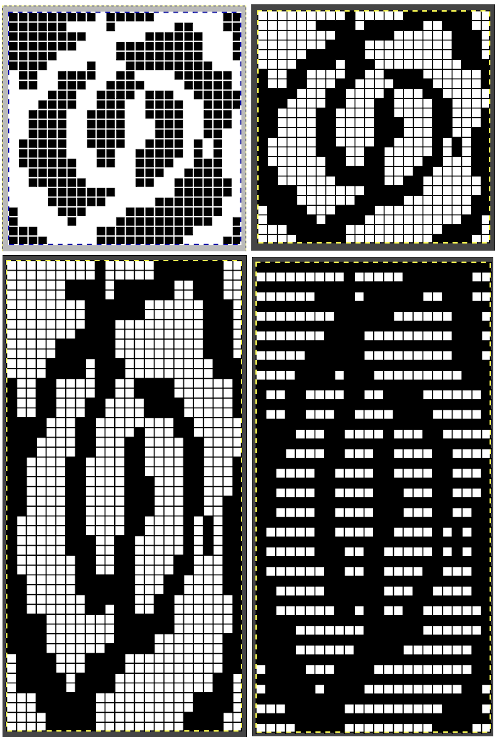

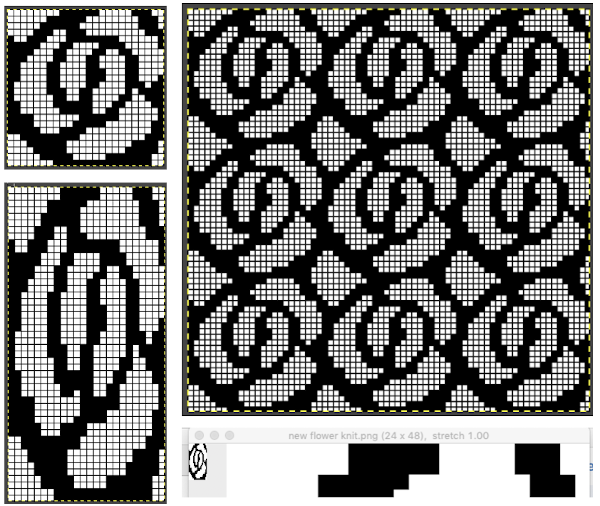

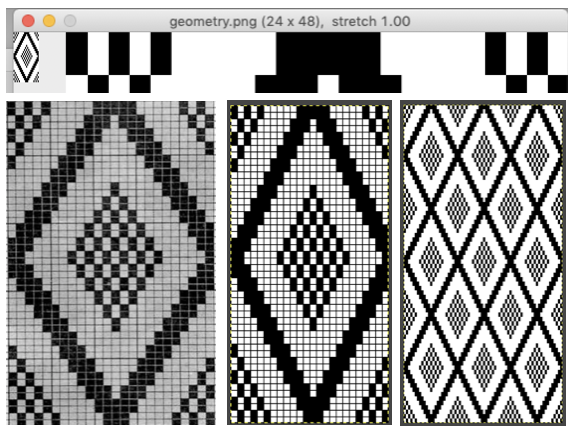

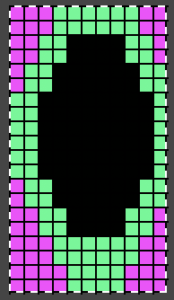

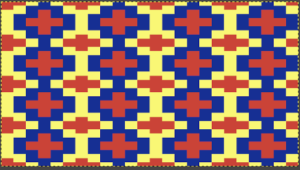

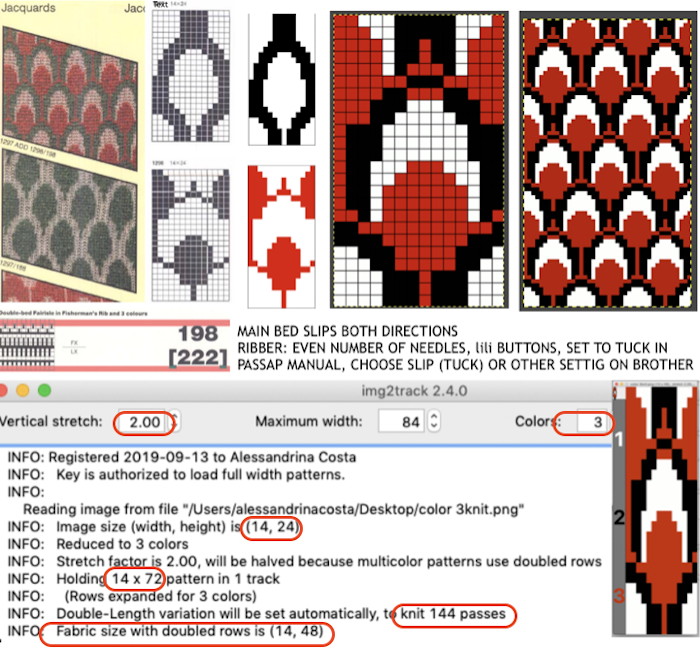

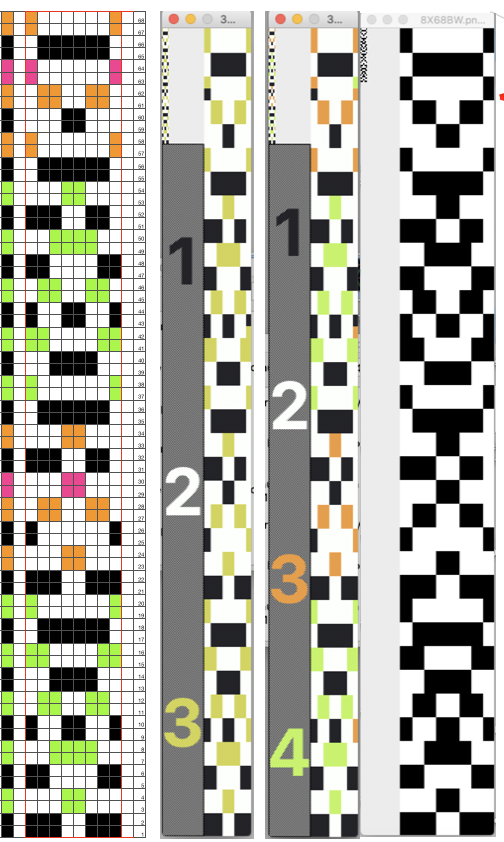

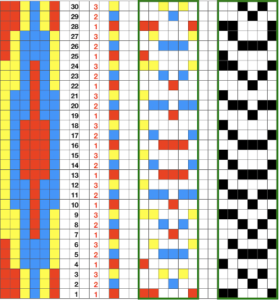

The  The repeat I chose is designated as suitable for the Garter Carriage. It is 24 stitches wide by 48 rows high, shown below as provided, charted in Gimp as .png for download, and tiled to help visualize how continuous repeats might line up. The image .png was downloaded with img2track to my 930, with a stretch factor of 1.0, retaining the original repeat size

The repeat I chose is designated as suitable for the Garter Carriage. It is 24 stitches wide by 48 rows high, shown below as provided, charted in Gimp as .png for download, and tiled to help visualize how continuous repeats might line up. The image .png was downloaded with img2track to my 930, with a stretch factor of 1.0, retaining the original repeat size

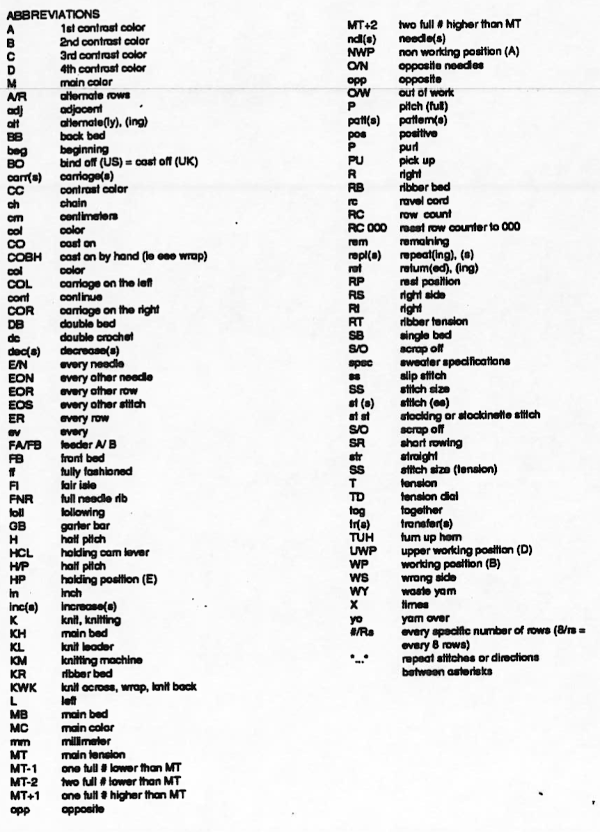

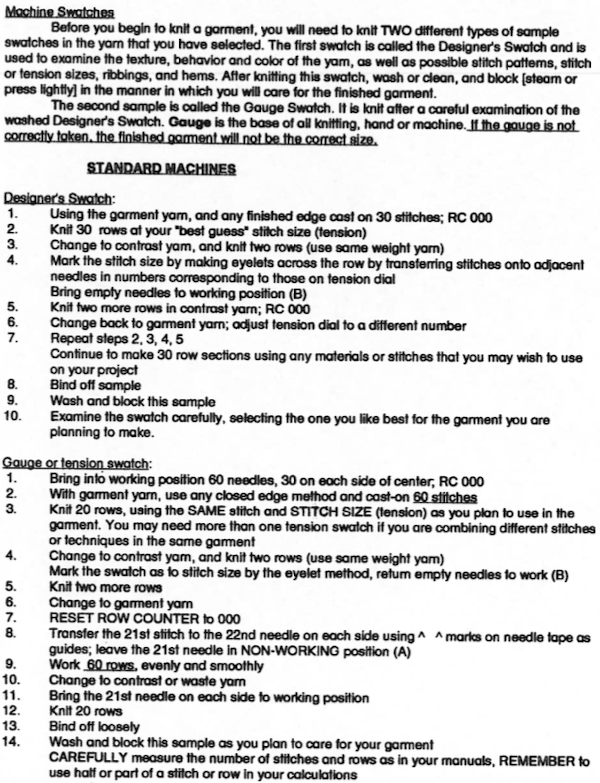

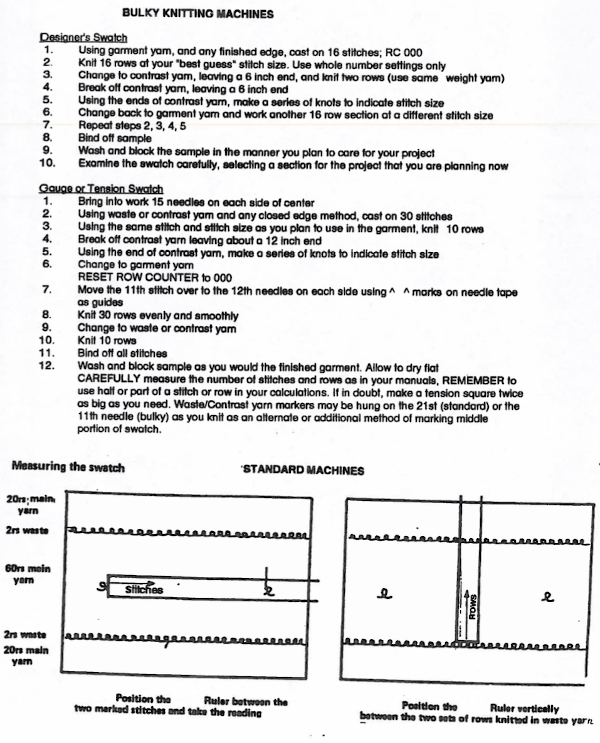

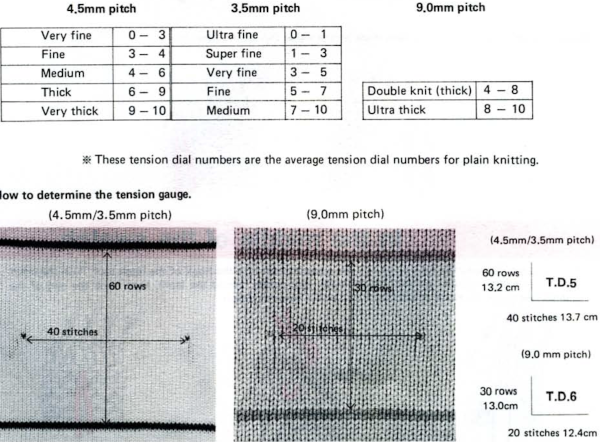

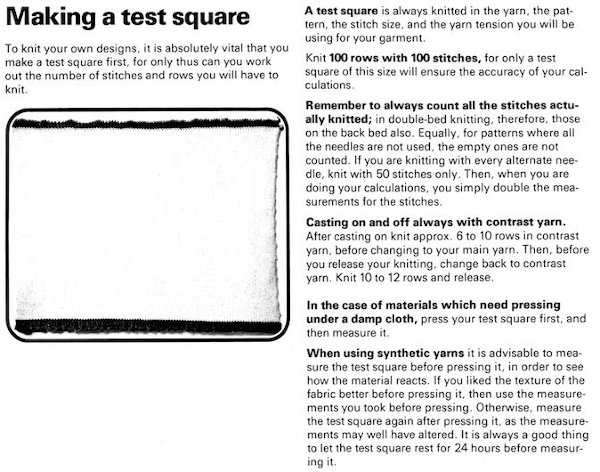

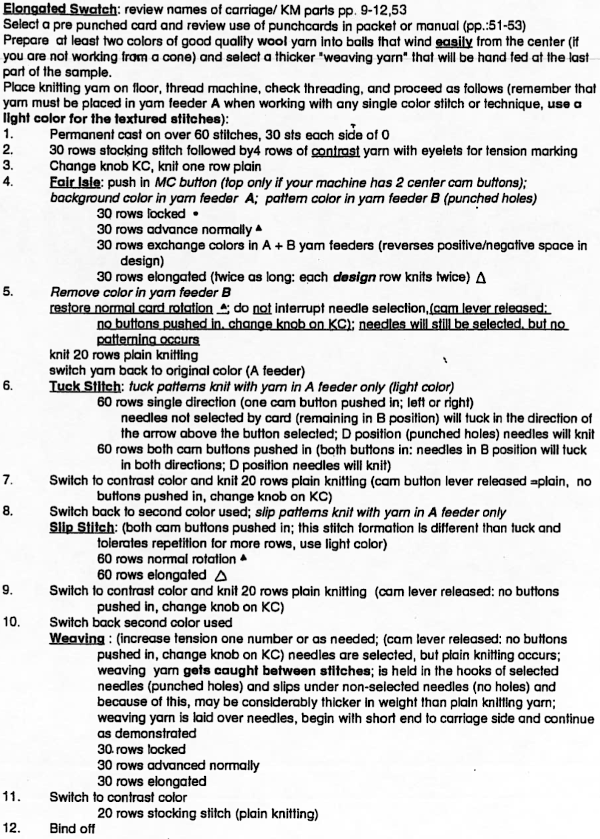

Test and gauge swatches

Test and gauge swatches

From the

From the

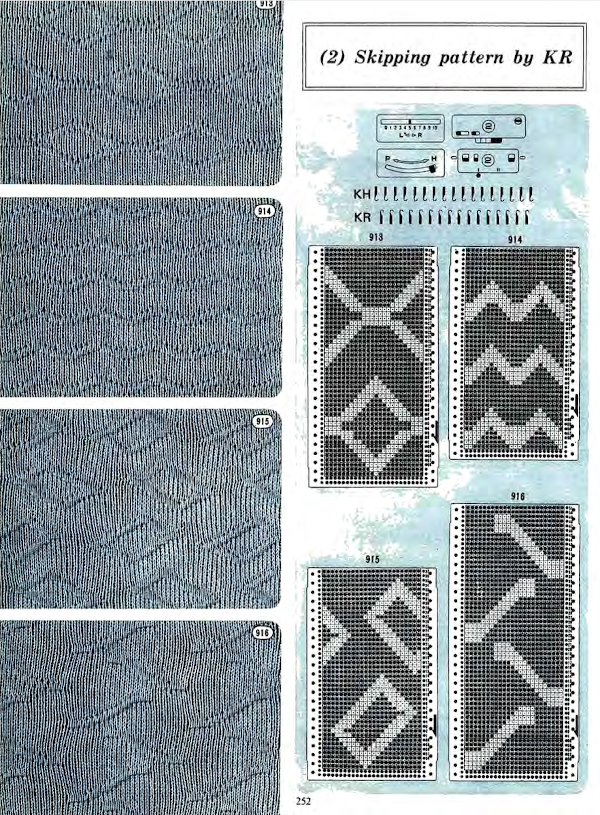

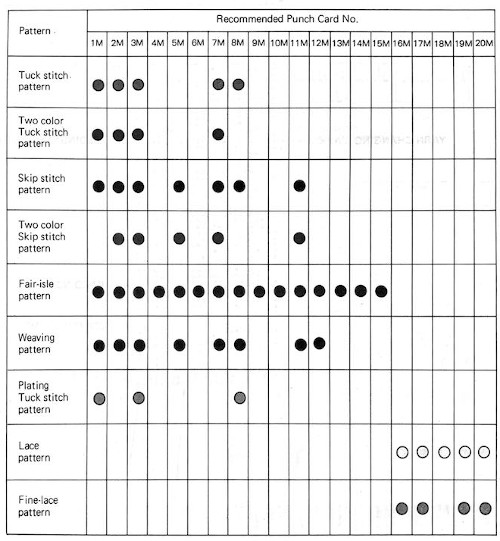

In KM model manuals a list was sometimes provided suggesting what cam settings might be suitable for each card

In KM model manuals a list was sometimes provided suggesting what cam settings might be suitable for each card

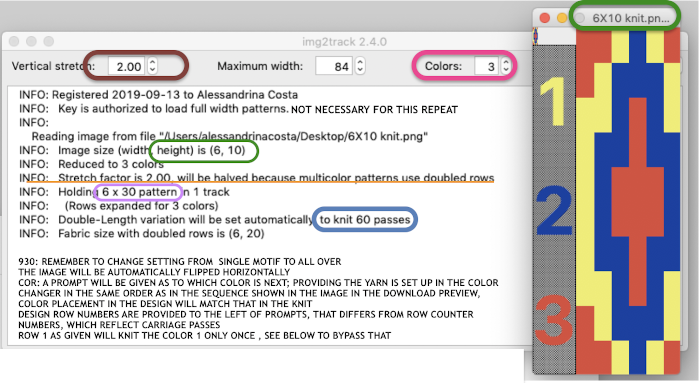

In the past, I have preferred to elongate the design prior to importing with plans for download rather than to rely on memory for changing settings either in the download program or in the machine itself in future uses of the same design.

In the past, I have preferred to elongate the design prior to importing with plans for download rather than to rely on memory for changing settings either in the download program or in the machine itself in future uses of the same design.

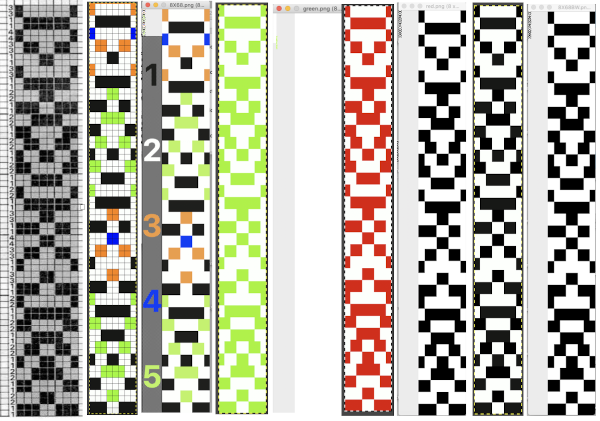

The same yarns, tension, the total number of carriage passes, and settings were used showing the difference in aspect ratio between single color per row knitting and the img2track built-in color separation.

The same yarns, tension, the total number of carriage passes, and settings were used showing the difference in aspect ratio between single color per row knitting and the img2track built-in color separation.  The width of both swatches is essentially identical.

The width of both swatches is essentially identical.

The 930 will provide prompts for the next color to be selected by pushing the matching number button on the color changer, avoiding any confusion in terms of what should be picked up next. img2track will also flip the design horizontally automatically so the image will appear as originally drawn on the knit side. Images are loaded as single motifs, so the change in the selector needs to be made manually for an all-over pattern.

The 930 will provide prompts for the next color to be selected by pushing the matching number button on the color changer, avoiding any confusion in terms of what should be picked up next. img2track will also flip the design horizontally automatically so the image will appear as originally drawn on the knit side. Images are loaded as single motifs, so the change in the selector needs to be made manually for an all-over pattern.

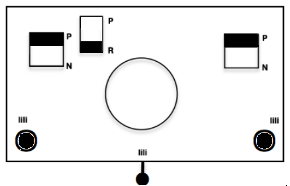

Obviously a success in terms of the single row for each color reducing elongation of the design shape. While knitting occurs using the same yarns, at the same tensions, there is a clear difference in the length of each stitch on the main bed and their appearance. The reverse. Checking the ribber carriage I noticed on the left side it was set to knit only, not to slip: OOPS!

Obviously a success in terms of the single row for each color reducing elongation of the design shape. While knitting occurs using the same yarns, at the same tensions, there is a clear difference in the length of each stitch on the main bed and their appearance. The reverse. Checking the ribber carriage I noticed on the left side it was set to knit only, not to slip: OOPS!  N is king, so the ribber set as shown is knitting every other needle when moving to the right, but even with lili buttons in use, it knits on every needle when moving back to the left. Every other needle on the ribber will then be knitting for 2 rows as a result. The more knitting on the ribber for each pair of rows, the longer the stitches on the opposite bed. The backing is an interesting variation (half) birdseye. The elongated stitches on the main bed show more of the backing in between their shapes, it is referred to as bleedthrough. In some instances, the result can make the knit surface resemble weaving and its appearance far less familiar in a surprising, pleasant way. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

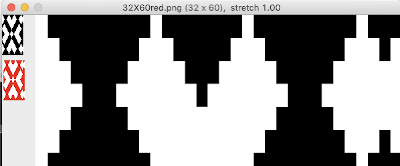

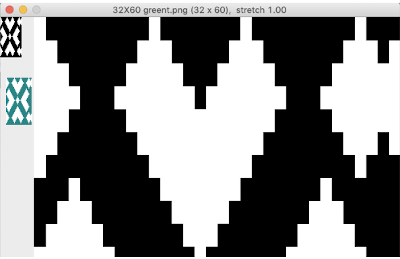

N is king, so the ribber set as shown is knitting every other needle when moving to the right, but even with lili buttons in use, it knits on every needle when moving back to the left. Every other needle on the ribber will then be knitting for 2 rows as a result. The more knitting on the ribber for each pair of rows, the longer the stitches on the opposite bed. The backing is an interesting variation (half) birdseye. The elongated stitches on the main bed show more of the backing in between their shapes, it is referred to as bleedthrough. In some instances, the result can make the knit surface resemble weaving and its appearance far less familiar in a surprising, pleasant way. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The images could be replicated as given in a paint program, using only one color for the squares, but “should be reduced to black and white”. Attempting to import an indexed 2-color image drawn in a color other than BW may result in strange results.

The images could be replicated as given in a paint program, using only one color for the squares, but “should be reduced to black and white”. Attempting to import an indexed 2-color image drawn in a color other than BW may result in strange results.  That said, if glitched knits are the goal, the above could work just fine. Curiously, here is the same process, using a different color, and a successful import. Checking again, I had forgotten to save the image after indexing it from RGB mode to 2 colors.

That said, if glitched knits are the goal, the above could work just fine. Curiously, here is the same process, using a different color, and a successful import. Checking again, I had forgotten to save the image after indexing it from RGB mode to 2 colors.

Note to self: if you are determined to use a punchcard carriage on your electronic machine remember there is no KCII to cancel end needle selection!

Note to self: if you are determined to use a punchcard carriage on your electronic machine remember there is no KCII to cancel end needle selection!

Getting that first row to knit twice instead of a single time if that matters in your technique or is your preference:

Getting that first row to knit twice instead of a single time if that matters in your technique or is your preference:

pick up color 1 in yarn changer

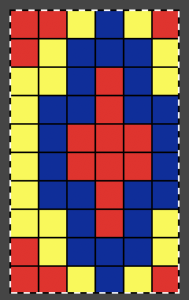

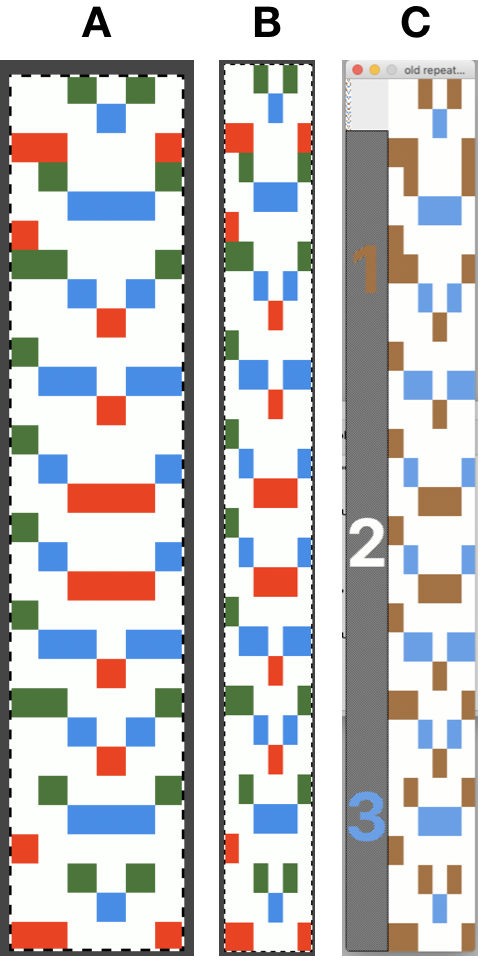

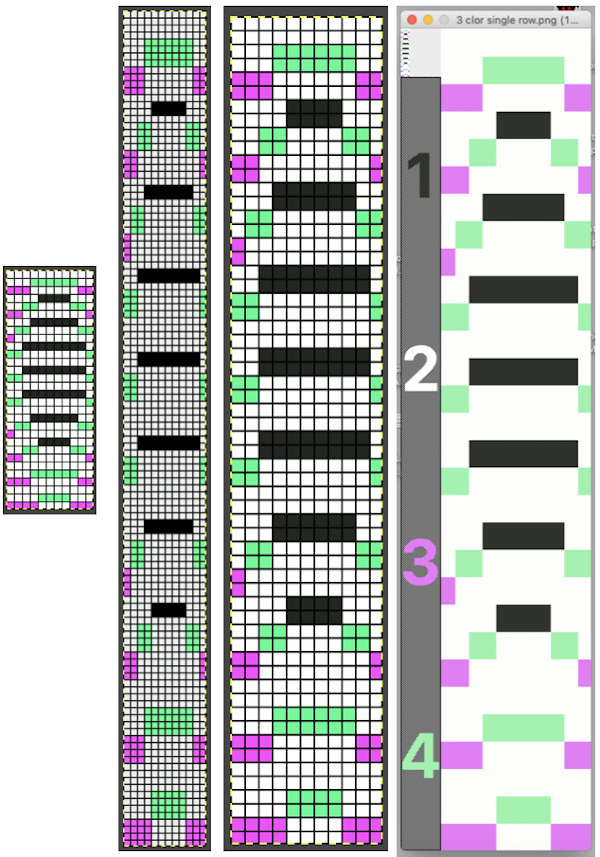

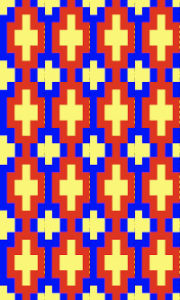

pick up color 1 in yarn changer If black and white repeats are already in your library, one may easily recycle them adding a third color. Here I did so with a repeat intended for a very different topic in future posts. The image was altered and tiled in Gimp for a repeat alignment test and is also shown imported into img2track for possible knitting.

If black and white repeats are already in your library, one may easily recycle them adding a third color. Here I did so with a repeat intended for a very different topic in future posts. The image was altered and tiled in Gimp for a repeat alignment test and is also shown imported into img2track for possible knitting.

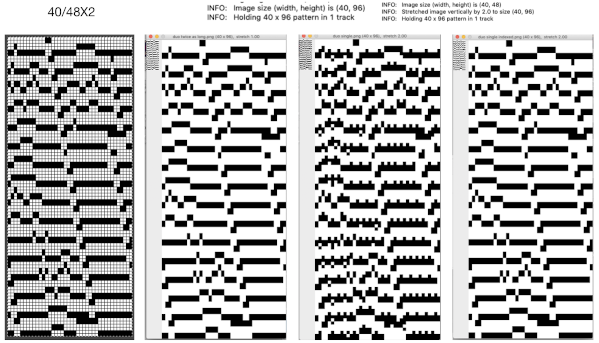

The image of the separation on the above right has not been proofed for accuracy. If it were, the next step would be to elongate it X 2 for color changes every 2 rows. One method is to elongate the original in a paint or photo processing program. The width is fixed (40), the height is scaled X 2. The resulting BW indexed image may be imported, using a 1.0 stretch factor, it remains unchanged. When I tried to elongate the unstretched image in img2track by 2.0 my first try failed. It turned out the reason was I had saved the import without first indexing it to 2 colors. With that corrected, the result matched the one from scaling X 2 in height in the paint program

The image of the separation on the above right has not been proofed for accuracy. If it were, the next step would be to elongate it X 2 for color changes every 2 rows. One method is to elongate the original in a paint or photo processing program. The width is fixed (40), the height is scaled X 2. The resulting BW indexed image may be imported, using a 1.0 stretch factor, it remains unchanged. When I tried to elongate the unstretched image in img2track by 2.0 my first try failed. It turned out the reason was I had saved the import without first indexing it to 2 colors. With that corrected, the result matched the one from scaling X 2 in height in the paint program

Here the image is scaled properly for each color represented for a single row in height and also scaled again for double height for possible knitting in Gimp. The Gimp scaling failed to be accurate for me (second image from left) until I indexed the original to 4 colors as well instead of 3. The no-color rows as we view them serve as a fourth color in the separations. Importing the proper size PNG into img2track for the separation of 4 colors per row now gives results that make sense: note the daunting estimate for the total number of carriage passes for a single repeat height

Here the image is scaled properly for each color represented for a single row in height and also scaled again for double height for possible knitting in Gimp. The Gimp scaling failed to be accurate for me (second image from left) until I indexed the original to 4 colors as well instead of 3. The no-color rows as we view them serve as a fourth color in the separations. Importing the proper size PNG into img2track for the separation of 4 colors per row now gives results that make sense: note the daunting estimate for the total number of carriage passes for a single repeat height If the ribber has knit on every needle by its return to the color changer and the machine is set to slip both ways with no needle selection on the main bed, the “no color” can be executed as an empty yarn holder in the color changer combined with no yarn in the feeder. The rows involved should simply not knit on the top bed, with no dropping of any of its stitches since no needles will have been selected thus coming forward with the yarn in the hooks and traveling behind the latches and in turn, slipping off the needles as a carriage with no yarn pushes the needles with now empty hooks back to B position.

If the ribber has knit on every needle by its return to the color changer and the machine is set to slip both ways with no needle selection on the main bed, the “no color” can be executed as an empty yarn holder in the color changer combined with no yarn in the feeder. The rows involved should simply not knit on the top bed, with no dropping of any of its stitches since no needles will have been selected thus coming forward with the yarn in the hooks and traveling behind the latches and in turn, slipping off the needles as a carriage with no yarn pushes the needles with now empty hooks back to B position.

Punchcard knitters may have the easiest knitting variable color sequences since cards may be visually marked up with colored pencils matching needed change locations and taking into account your eyes are several rows above the row being read by the card reader. This number depends on the machine’s brand and model.

Punchcard knitters may have the easiest knitting variable color sequences since cards may be visually marked up with colored pencils matching needed change locations and taking into account your eyes are several rows above the row being read by the card reader. This number depends on the machine’s brand and model.

the initial method:

the initial method:

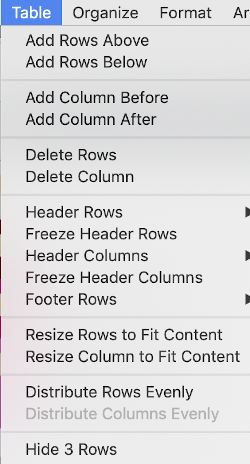

following that up, I planned for the 60 rows needed to complete the repeat, hid 30 rows, using this menu

following that up, I planned for the 60 rows needed to complete the repeat, hid 30 rows, using this menu copied and pasted the black and white repeat on the above right, then unhid the 30 hidden rows (see previous posts using command key selections), having a new color separation repeat, created the final 2 color BMP in Gimp (whew!)

copied and pasted the black and white repeat on the above right, then unhid the 30 hidden rows (see previous posts using command key selections), having a new color separation repeat, created the final 2 color BMP in Gimp (whew!) Since my separation is planned on 2-row sequences, I began with COR and my preselection row was from right to left.

Since my separation is planned on 2-row sequences, I began with COR and my preselection row was from right to left.

Again, there is some bleed-through, and even with this technique there is some elongation of each of the shapes, but less so than with other techniques. The backing of all these fabrics produces single lines in each color used

Again, there is some bleed-through, and even with this technique there is some elongation of each of the shapes, but less so than with other techniques. The backing of all these fabrics produces single lines in each color used  Even fairly small repeats can take time to color separate in this manner. The technique, however, is the only method available to punchcard knitters. Electronic machines with download cables and varying software open a very different world in terms of ease and range in repeat size possibilities.

Even fairly small repeats can take time to color separate in this manner. The technique, however, is the only method available to punchcard knitters. Electronic machines with download cables and varying software open a very different world in terms of ease and range in repeat size possibilities.

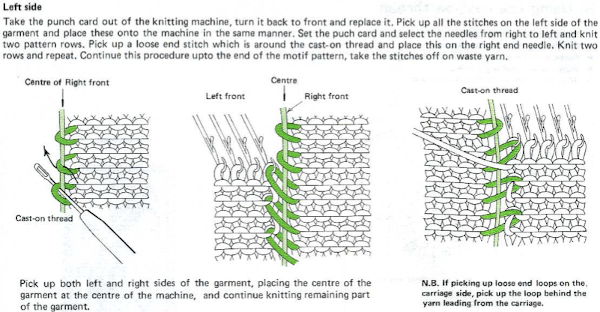

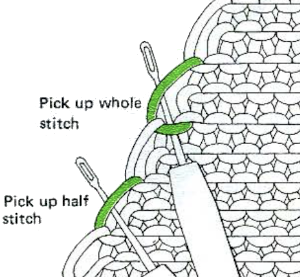

Open stitches may also be joined using this method, but they would have to be hooked onto the second piece every row rather than every other, and caution should be taken in terms of skipping any stitch, as any such stitch will unravel at the end of the process unless it has been secured.

Open stitches may also be joined using this method, but they would have to be hooked onto the second piece every row rather than every other, and caution should be taken in terms of skipping any stitch, as any such stitch will unravel at the end of the process unless it has been secured.

This is a long-ago demo swatch. The chevrons are shaped by holding, could be knit on any machine in any width. After the first strip is knit to the desired length, the second is joined to it as it is being knit. I generally prefer the joins with the carriage on the right and the completed strip hooked onto its left side. If the color changer is to be used, then the strip being created to join to the finished piece should always be knit on the left side of the bed in order to allow for traveling to and from the color changer every 2 rows. The image here is turned sideways, the chevrons could be used either vertically or horizontally depending on the design plans.

This is a long-ago demo swatch. The chevrons are shaped by holding, could be knit on any machine in any width. After the first strip is knit to the desired length, the second is joined to it as it is being knit. I generally prefer the joins with the carriage on the right and the completed strip hooked onto its left side. If the color changer is to be used, then the strip being created to join to the finished piece should always be knit on the left side of the bed in order to allow for traveling to and from the color changer every 2 rows. The image here is turned sideways, the chevrons could be used either vertically or horizontally depending on the design plans.

The above method may be used to join fair isle patterns in order to achieve significantly wider final panels. Some artists, when no electronic models were available, would join cards in continued lengths and plan their repeats side by side to achieve large, non-repetitive images. The punchcard width markings on your Brother needle tape can serve as guides. I use punchcard repeats so often I replaced the needle tape in my 910 early on with one for punchcard models. Markings may also be seen on them for every 8 stitches

The above method may be used to join fair isle patterns in order to achieve significantly wider final panels. Some artists, when no electronic models were available, would join cards in continued lengths and plan their repeats side by side to achieve large, non-repetitive images. The punchcard width markings on your Brother needle tape can serve as guides. I use punchcard repeats so often I replaced the needle tape in my 910 early on with one for punchcard models. Markings may also be seen on them for every 8 stitches

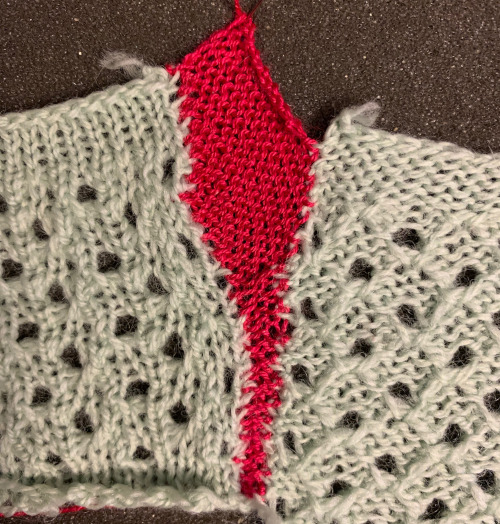

Here a slip-stitch ruffle was joined on the left to one of my completed shawl bodies.

Here a slip-stitch ruffle was joined on the left to one of my completed shawl bodies.

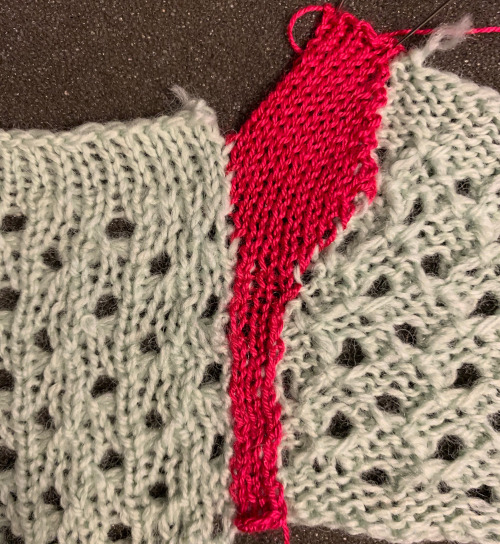

and continued until I reached the point where I wanted to experiment with increases, keeping the shape symmetrical. I picked up a loop from both added pieces and hooked them onto the first empty needle on each side of the strip, essentially casting on an added stitch on each side each time, following with 2 knit rows.

and continued until I reached the point where I wanted to experiment with increases, keeping the shape symmetrical. I picked up a loop from both added pieces and hooked them onto the first empty needle on each side of the strip, essentially casting on an added stitch on each side each time, following with 2 knit rows.  After working on my “desired shape” I tested decreases:

After working on my “desired shape” I tested decreases: COR: after hooking up the next row, knit one row to the left

COR: after hooking up the next row, knit one row to the left

The cleanest joins happen when the edges are straight to start with, above there was a movement of the edges happening because of the distortion of the fabric created by the eyelets. A light pressing if possible may also set the edge stitches, help them lie flat, and make them more visible. When working with slanted edges on the first piece this is one way to join it, taking into consideration whether any adjustment in the frequency of hooking up needs to be made.

The cleanest joins happen when the edges are straight to start with, above there was a movement of the edges happening because of the distortion of the fabric created by the eyelets. A light pressing if possible may also set the edge stitches, help them lie flat, and make them more visible. When working with slanted edges on the first piece this is one way to join it, taking into consideration whether any adjustment in the frequency of hooking up needs to be made.

the knit side, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right

the knit side, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right  every other needle, purl side facing, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right, with markers indicating the “extra float”

every other needle, purl side facing, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right, with markers indicating the “extra float”  the knit side, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right

the knit side, 2 circs on left, 3 on the right

proceeding toward the yarn end, pick up one of the next 2 loops in the hook, here I consistently chose the one on the right

proceeding toward the yarn end, pick up one of the next 2 loops in the hook, here I consistently chose the one on the right  if the first loop slips in the hook again as well, get it behind the latch once more before proceeding

if the first loop slips in the hook again as well, get it behind the latch once more before proceeding pull the second loop through the previous one

pull the second loop through the previous one  work across the row, secure the yarn end

work across the row, secure the yarn end  the appearance on the reverse side

the appearance on the reverse side  I can be a little bonkers with my finishing, have even been known when dealing with getting top and bottom edges to match in look and width to rehang every other loop, knit a row, and then perform the latch tool bind off. If tuck double bed fabrics are knit, they require planning for loose cast-ons and bind-offs. Slip stitch is short and thin, tuck stitch is short and fat, whether knit single or double bed and then is compared with fabrics where either bed predominantly knits plain.

I can be a little bonkers with my finishing, have even been known when dealing with getting top and bottom edges to match in look and width to rehang every other loop, knit a row, and then perform the latch tool bind off. If tuck double bed fabrics are knit, they require planning for loose cast-ons and bind-offs. Slip stitch is short and thin, tuck stitch is short and fat, whether knit single or double bed and then is compared with fabrics where either bed predominantly knits plain.

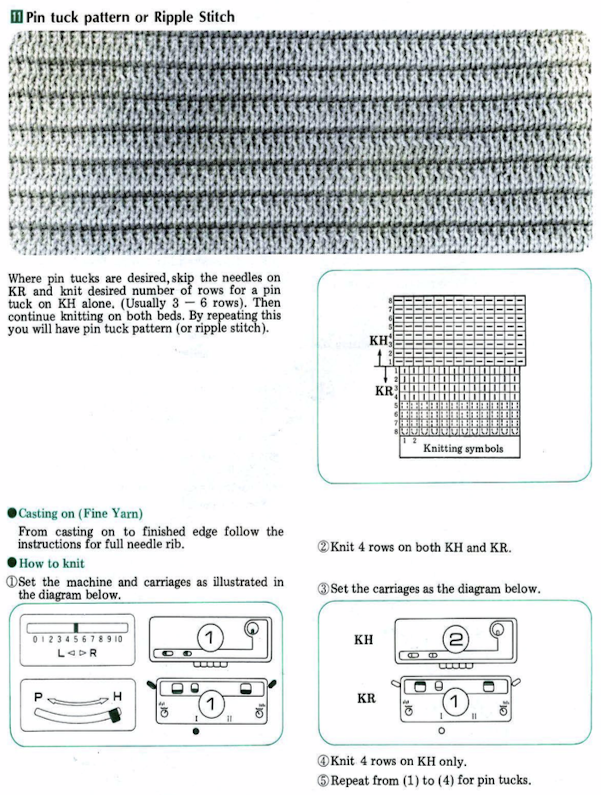

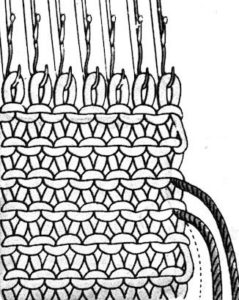

from the Brother Ribber techniques book

from the Brother Ribber techniques book