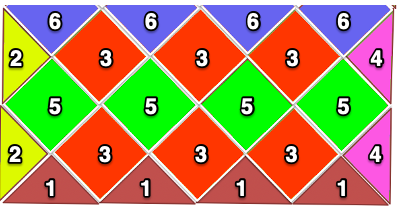

My recent revisiting of holding techniques led to my coming across handouts and notes from the late 1980s and early 90s, including the working notes below for an entrelac fabric. I sometimes read instructions I assembled long ago, and they seem to be in a foreign language at first. Entrelac was referred to as basketweave as well. On the knitting machine, it is usually executed removing part of shapes onto waste yarn. In these shared instructions it is knit completely on the machine. Blocks can be any size, knitting is started on a multiple of the stitches planned for each shape repeat. The number of colors used is limited by imagination and patience for weaving in yarn ends and dealing with issues at the start of each new shape, familiar to anyone who has tried intarsia. Weaving in those yarn ends may be performed during the knitting of larger “diamonds”. It is helpful to understand the basics of short rowing prior to attempting this technique.

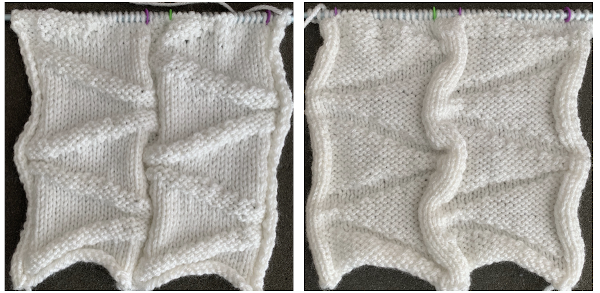

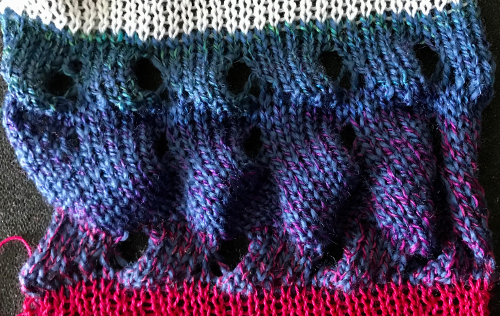

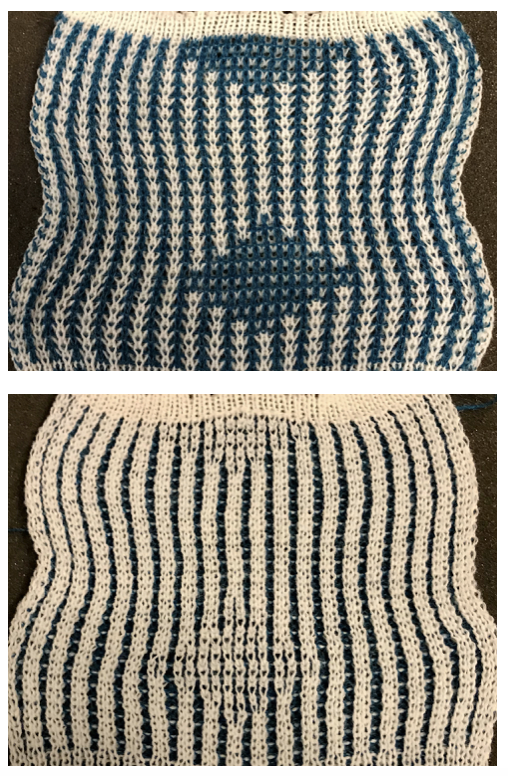

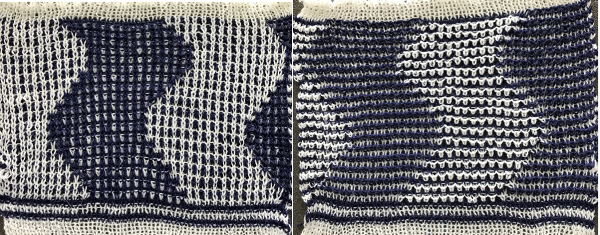

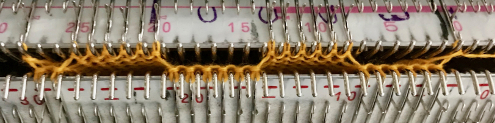

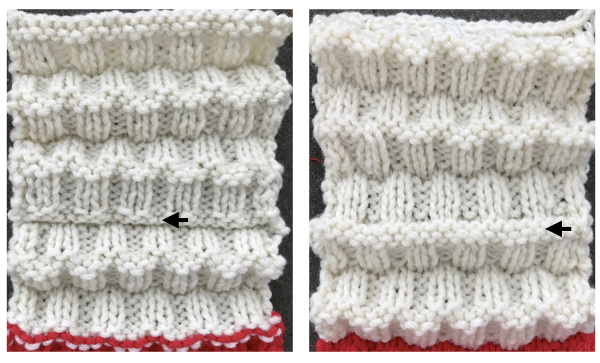

In a post in 2011, I shared a link to excellent directions found at howtoknitasweater.com , written by Cheryl Brunette. Here are 2 of my teaching samples, executed on 4.5 mm machine. In my teaching days, my demo yarns were in distinct colors, easily spotted, and not often preferred or even liked by students. They could be instantly recognized, so no one ever tried to use them in their class assignments, and colors were out of range for the comfort level of attendees at my workshops, so swatches tended to remain mine for the duration of those sessions and far beyond.

a rearview with ends woven in

a rearview with ends woven in

It is best to start with a few rows of waste yarn, and the choice can then be made as to whether to cast on and go immediately into pattern, or ribs, stocking stitch, or other beginnings and endings may be chosen.

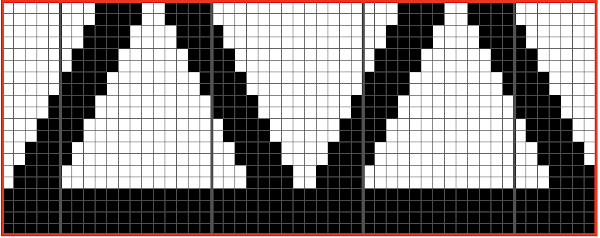

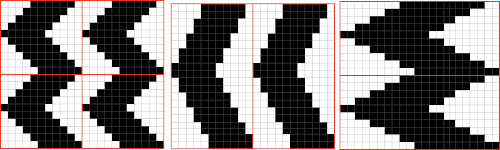

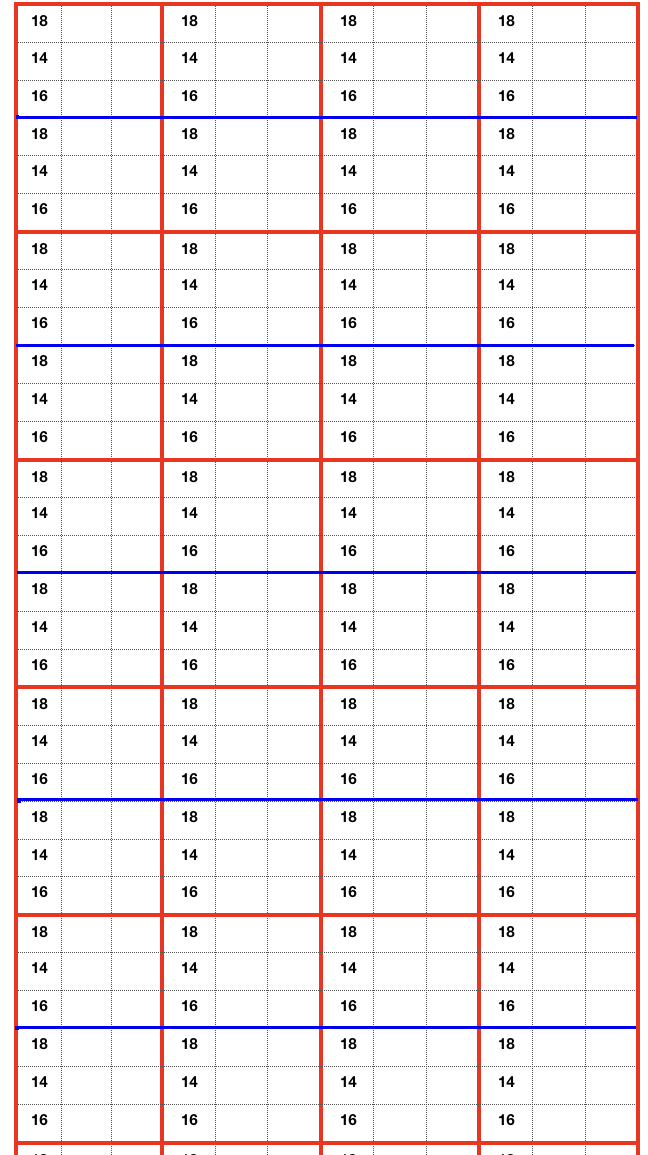

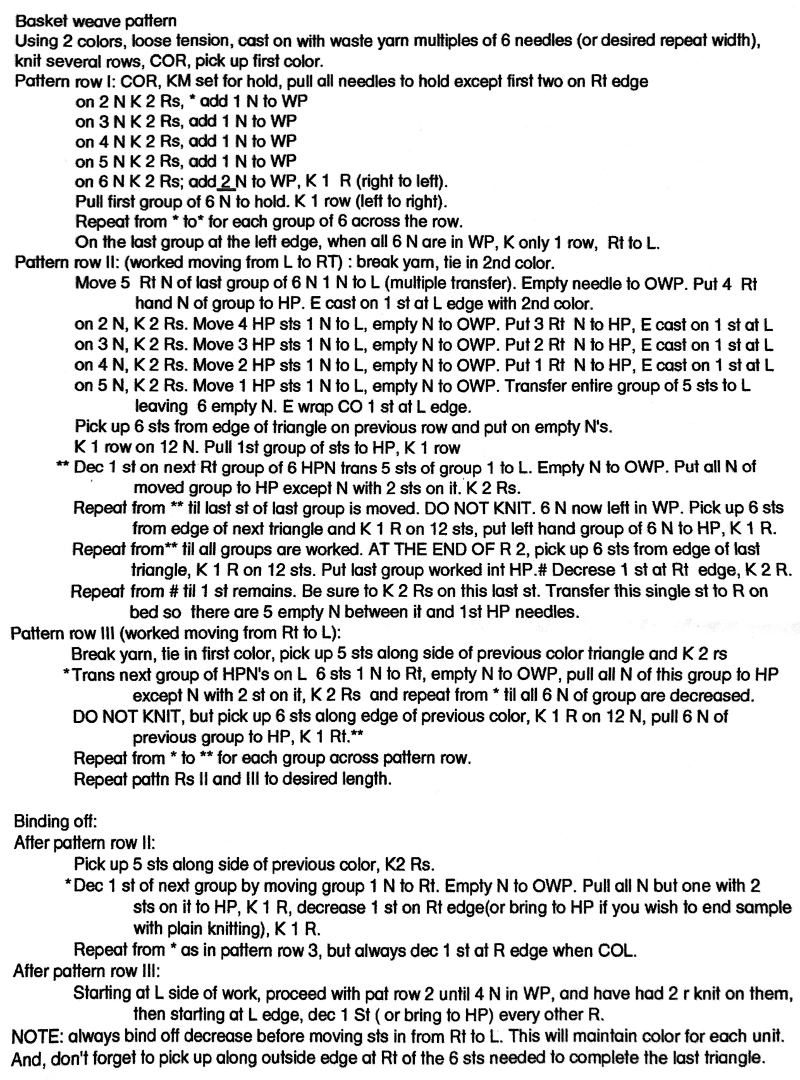

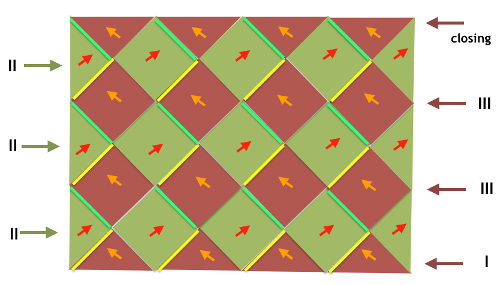

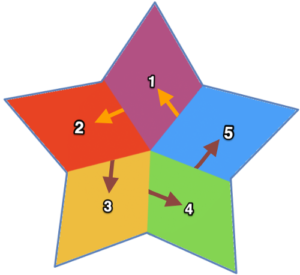

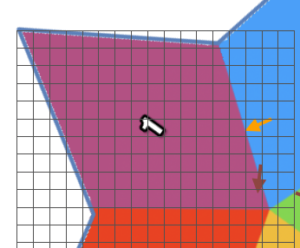

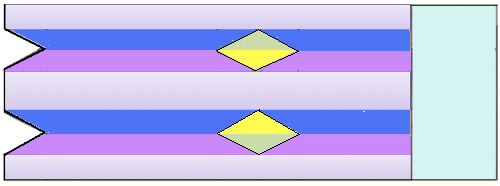

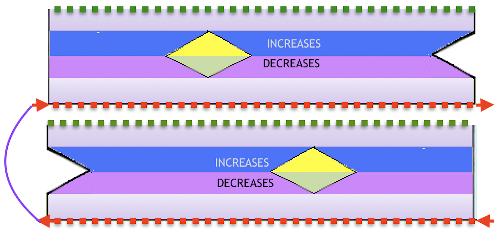

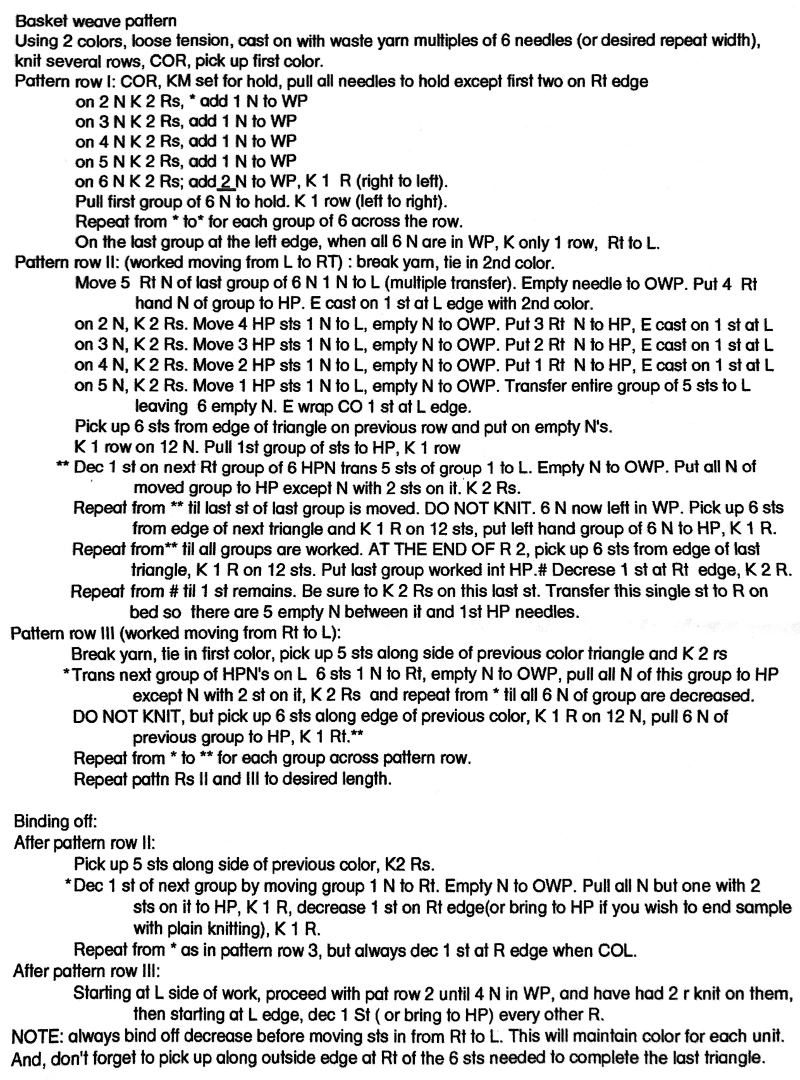

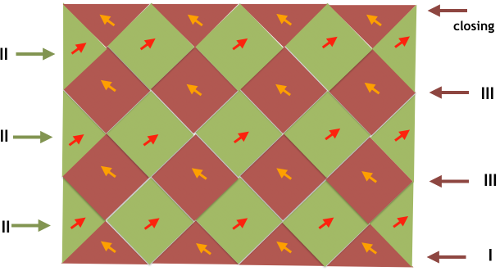

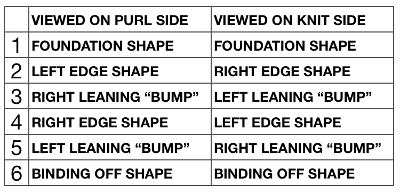

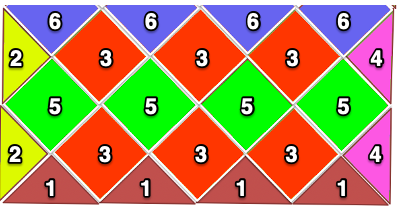

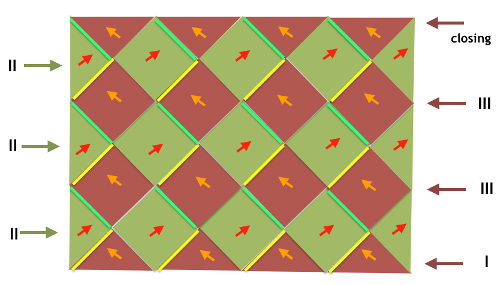

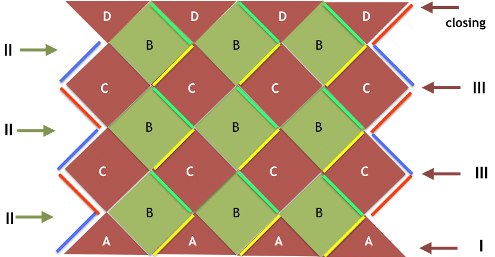

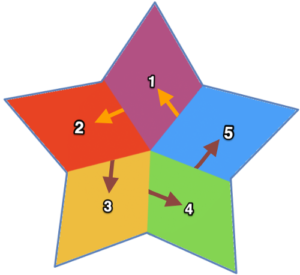

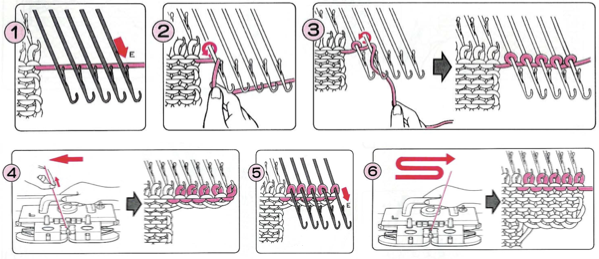

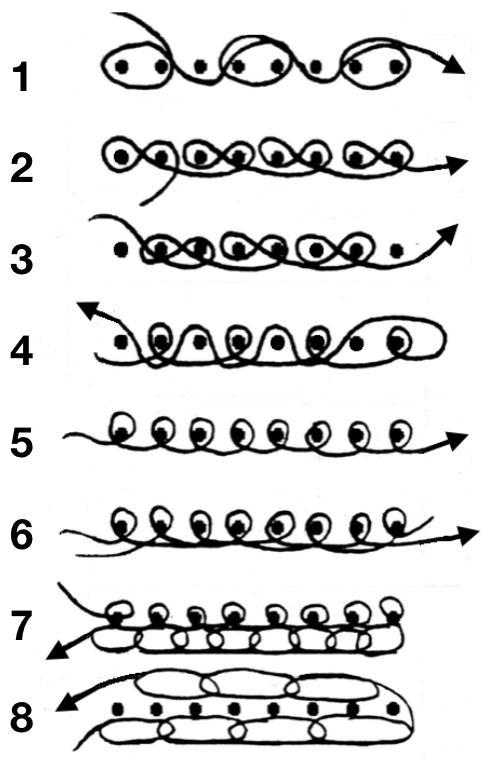

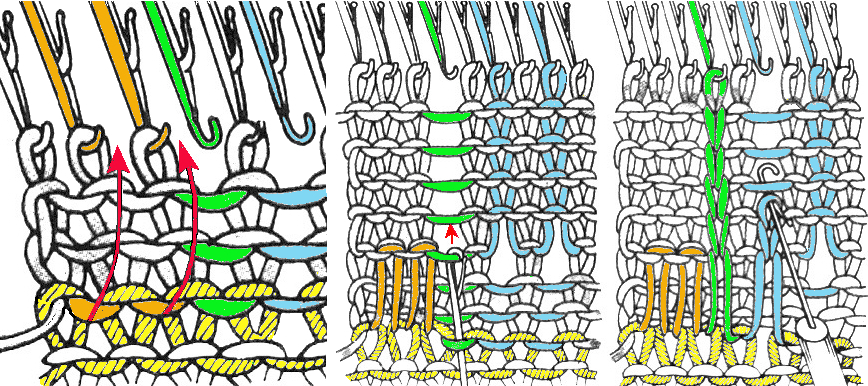

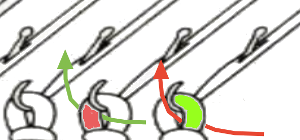

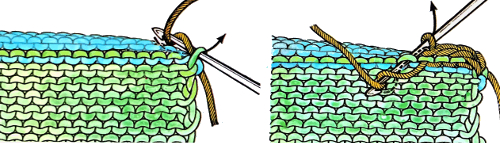

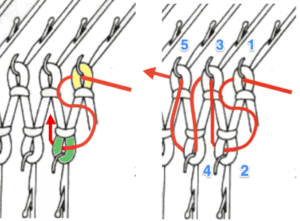

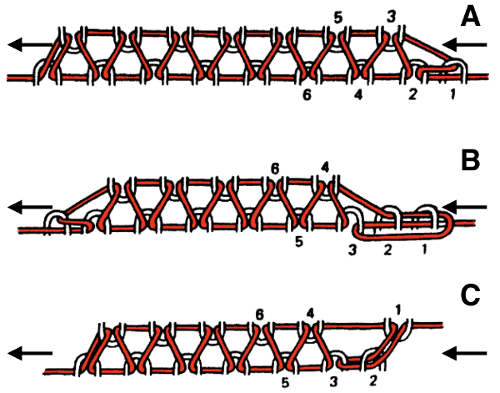

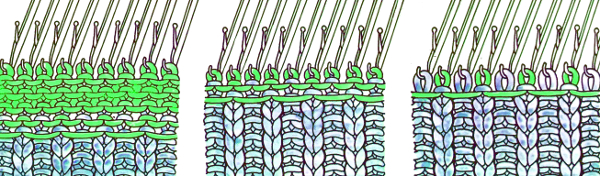

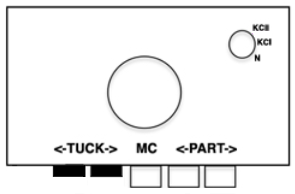

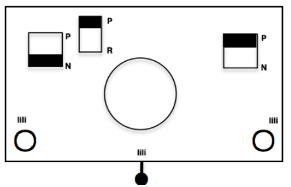

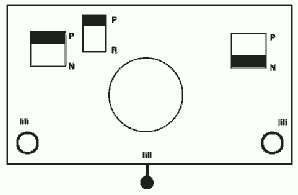

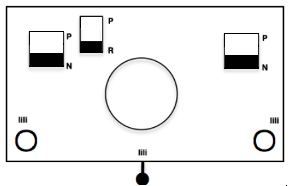

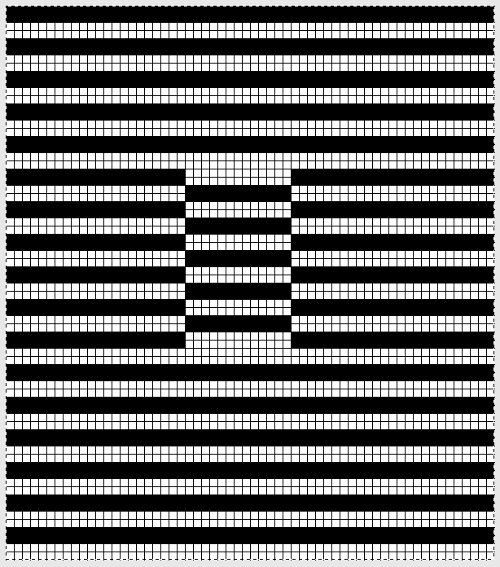

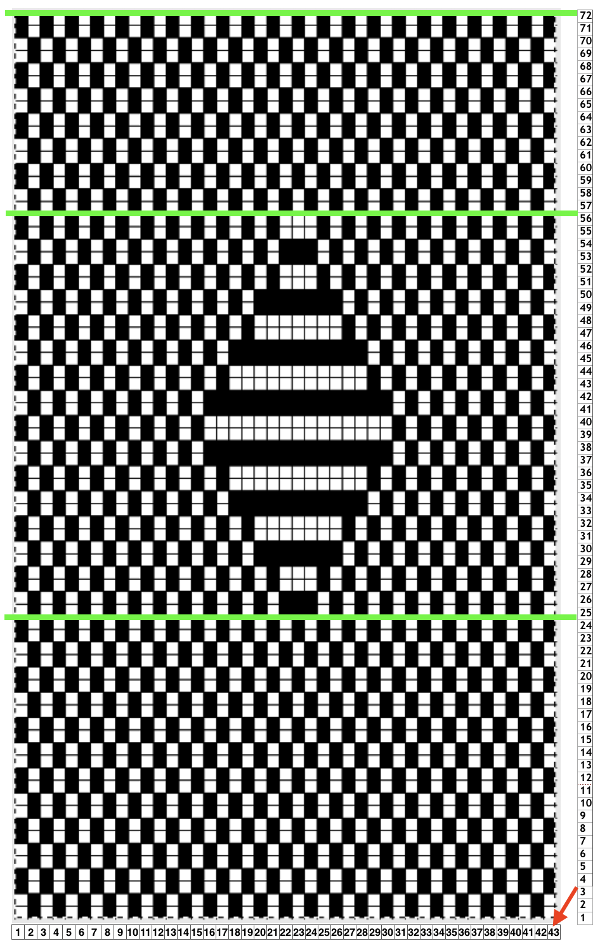

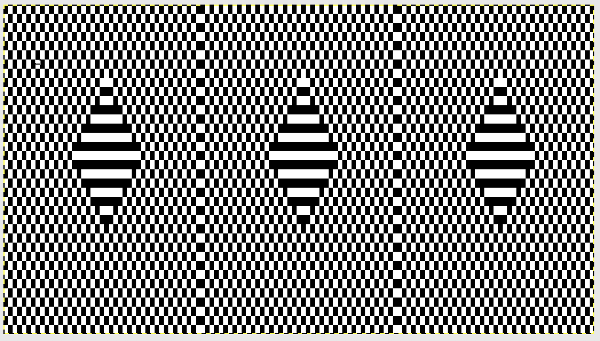

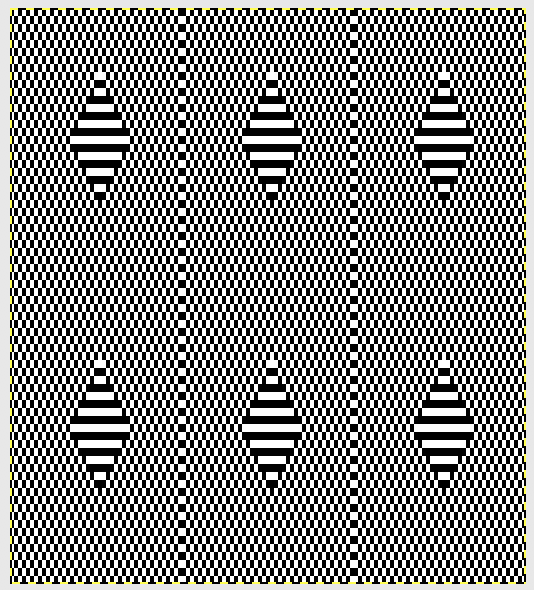

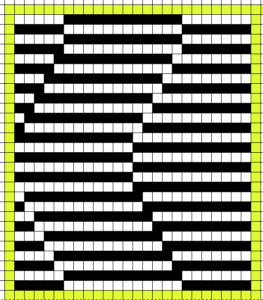

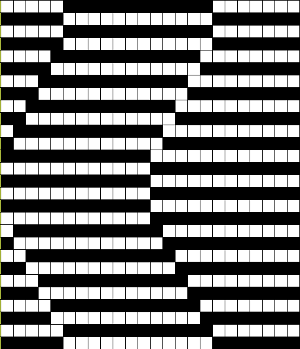

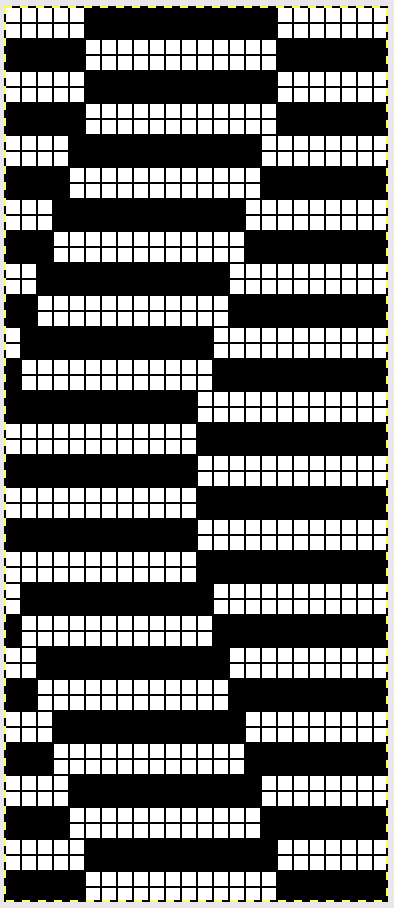

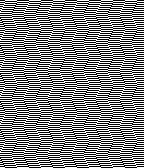

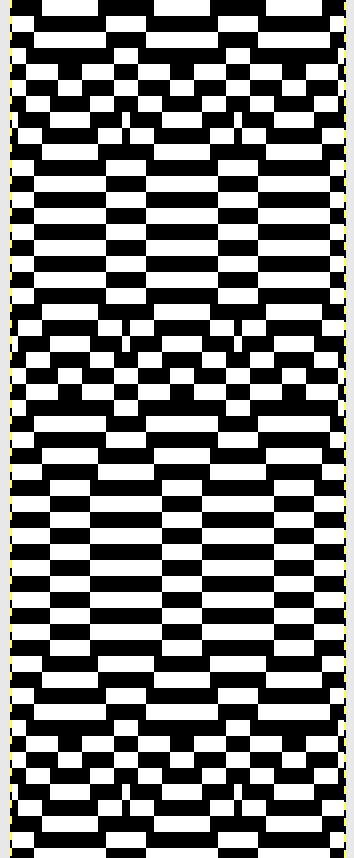

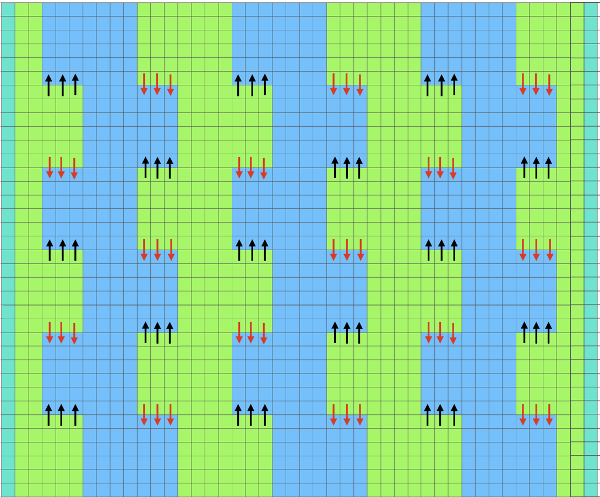

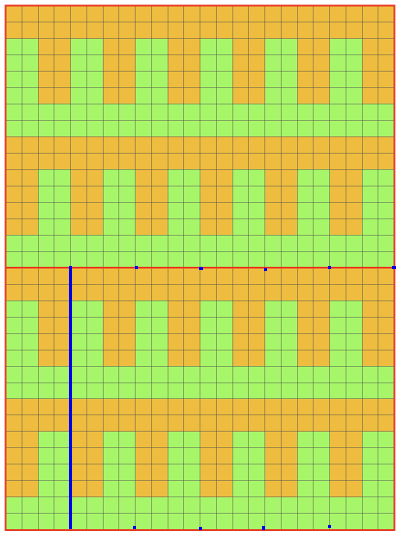

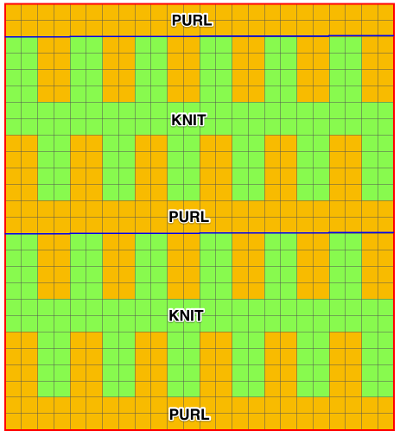

The blocks will appear square to rectangular depending on yarn choice and gauge, some writers refer to them as “diamonds”, they are joined together as you knit. My test swatches are all executed on Brother machines. My own working notes:  Visualization: here pattern rows II and III are shown in repeat, along with the direction of the carriage movement, and the lean in the shapes created with the purl side facing

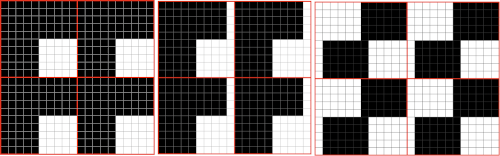

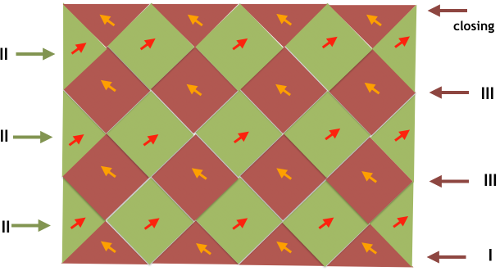

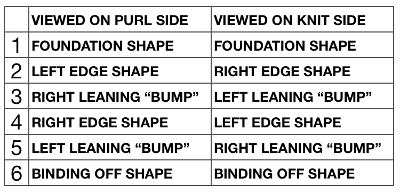

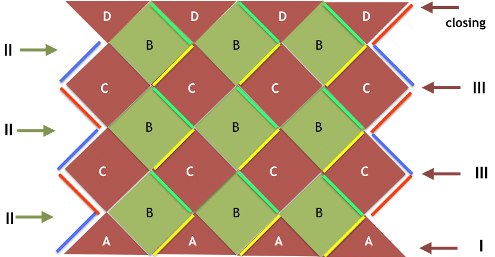

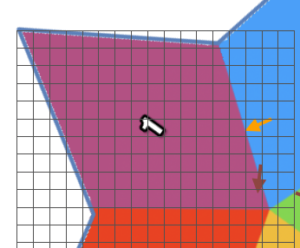

Visualization: here pattern rows II and III are shown in repeat, along with the direction of the carriage movement, and the lean in the shapes created with the purl side facing  This attempts to identify the shapes by assigning numbers, in their order of knitting. As mentioned, the fabric may also end with added rows of knitting on top of the last row of shapes as they are formed

This attempts to identify the shapes by assigning numbers, in their order of knitting. As mentioned, the fabric may also end with added rows of knitting on top of the last row of shapes as they are formed

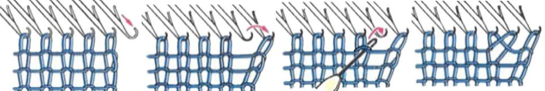

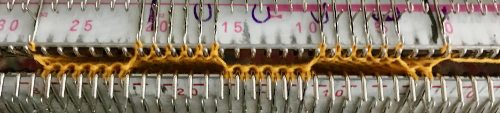

These photos do not document each step, are meant as an aid in parts that may be a bit tricky when starting to experiment with the technique

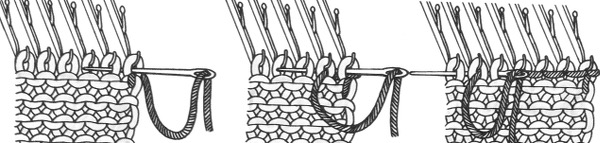

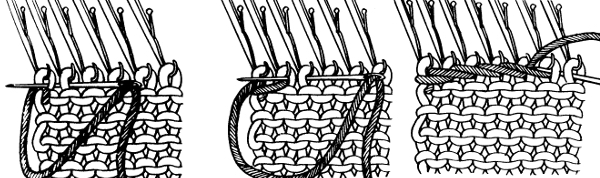

The set up for starting triangles: note the similarity to some of the surfaces created in the last post. When using short rows, part of the stitches in work will knit many more rows than others on the machine. Accessories such as the cast on comb will tend to ride up on one side and drop off  When the end of the first row that row is reached, as contrast color is added, stitches need to be cast on on the far left in order to keep the work on the bed a constant number of stitches. The usual method suggested is e wrapping, this is picking up from the row below. I found either method produced looser, longer stitches on the far edge

When the end of the first row that row is reached, as contrast color is added, stitches need to be cast on on the far left in order to keep the work on the bed a constant number of stitches. The usual method suggested is e wrapping, this is picking up from the row below. I found either method produced looser, longer stitches on the far edge  continuing across the row:

continuing across the row: reaching the far right:

reaching the far right:

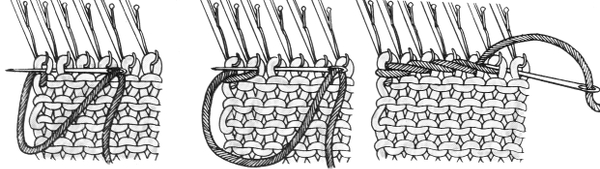

binding off across the row by transferring stitches when moving from right to left

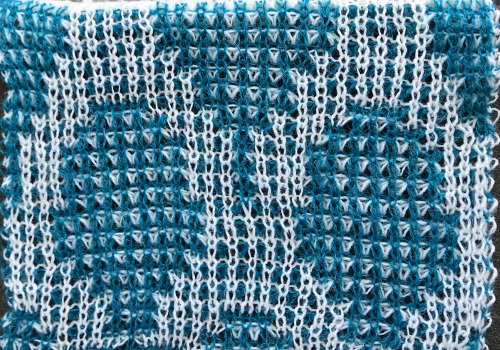

The colors were chosen for contrast, the yarns are slightly different thicknesses, the white is a 2/24. The latter is usually used double-stranded when knitting on the single bed unless intended as a “thin”. Bleedthrough at joins and some of the other features ie eyelets at corners might be reduced simply by making a better yarn choice. As for those “wisteria” eyelets, they could become part of an intentional pattern between bands of basket weave. Once the principle is understood many other variations become possible.

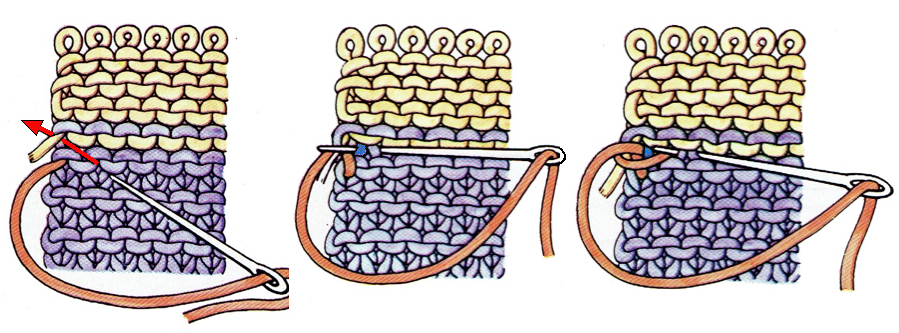

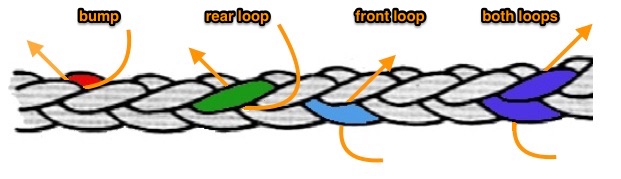

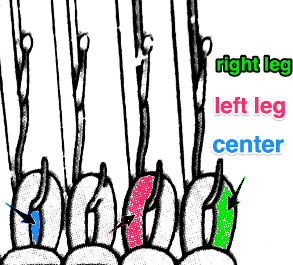

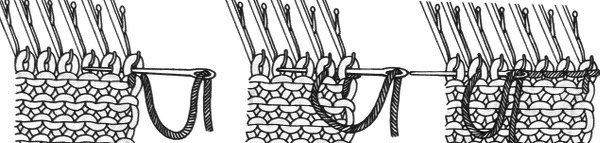

Many details in any technique wind up relying on personal preference for use of or added editing. Studying results on swatches can help one determine whether larger pieces are worth the effort, and what habits and their results may need to be changed. Contrasting colors help with evaluating edges in patterns such as these. This method relies on transferring groups of stitches by hand on the needle bed. The process could get far slower and impractical if the “diamonds” increase significantly in size. At the intersection of the shapes, there will appear an eyelet (1), also seen in hand knits, which disappears if the fabric is not stretched or pressed. How stitches are rehung in any part of the process can change the look of what is happening there as well. Picked up finished edges if tight will draw in the shape on that side (2), holding happens in 2-row sequences, and small eyelets happen there as well (3). Consistency matters. Though the shapes lean diagonally in the finished piece, they are picked up along straight edges, forming a square to a rectangular piece of knitting, with the usual grain, allowing for the addition of other techniques within the blocks

Trying to imagine where stitches may need transferring to waste yarn or “off label” tool? Alternative shapings at sides: what needs to be cast on or bound off?

Alternative shapings at sides: what needs to be cast on or bound off?

Troubleshooting ideas: a small weight might be enough to elongate those shorter closed edges to make them easier to rehang and to be a bit longer. Claw weights usually available with machines may be far too heavy, then DIY ones come into play. A common suggestion at MK seminars used to be that of purchasing fishing weights, which commonly come in a variety of sizes often with openings or wire eyelets at their top, and using bent wire or even paper clips so one hooked end can be inserted into the hole on the weight, the other is used to hang it in turn onto the knitting. This is an example Such weights are made of lead. That is a concern, there are products on the market that may be used to coat them. This one is easily found in home improvement stores and online

Such weights are made of lead. That is a concern, there are products on the market that may be used to coat them. This one is easily found in home improvement stores and online

This round sample in the absence of the paint was covered in heavy-duty duct tape. It weighs 2 ounces, just half of one of my factory-supplied claw weights It does a good job of weighing down those straight edges along the bumps, making the stitches easier to pick up. When rehanging those stitches, uniformly hanging the loops, not the knots along the edges involved will give a smoother join. Here a paper clip is used as the “hanger”

It does a good job of weighing down those straight edges along the bumps, making the stitches easier to pick up. When rehanging those stitches, uniformly hanging the loops, not the knots along the edges involved will give a smoother join. Here a paper clip is used as the “hanger” It is easy to get into a rhythm and think you “have it”. A reminder: the shapes at each side are triangles, not the full shape. Row II starts on the right, begins with decreases followed by rehanging, row III starts on the left, involves increases and working stitches in hold to its right. Losing track will produce the start of an extra shape, which may perhaps be a “design feature”, but not a good thing if the goal is a straight edge on both sides. Unraveling is easy if the problem is noticed soon, but is problematic if more rows of shapes have been completed.

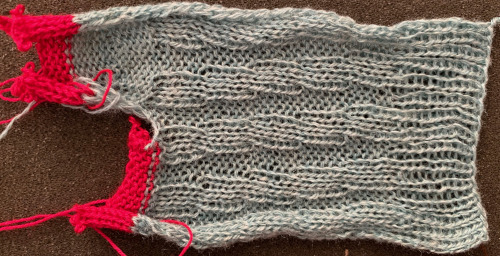

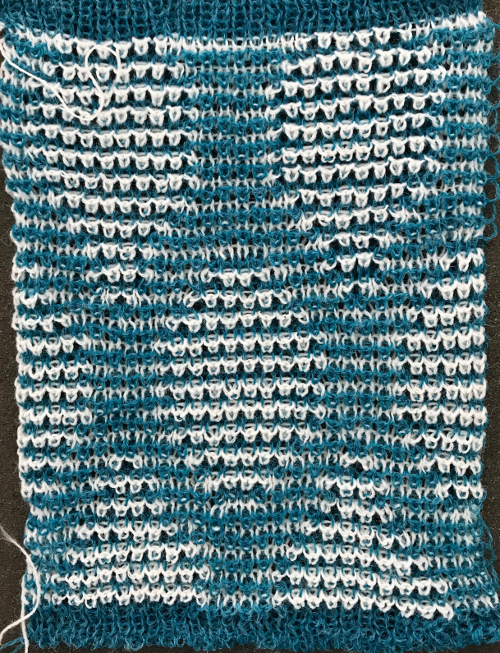

It is easy to get into a rhythm and think you “have it”. A reminder: the shapes at each side are triangles, not the full shape. Row II starts on the right, begins with decreases followed by rehanging, row III starts on the left, involves increases and working stitches in hold to its right. Losing track will produce the start of an extra shape, which may perhaps be a “design feature”, but not a good thing if the goal is a straight edge on both sides. Unraveling is easy if the problem is noticed soon, but is problematic if more rows of shapes have been completed.  Lastly, a swatch ending in all knit rows. The only remaining issue is the fact that those side triangles are formed by stitches that are looser than across the rest of the piece. This yarn is thin and a poor choice, but fine for getting the technique down and beginning to understand what happens to stitches, how one needs to move from one side to the other, and what happens along the edges of each individual shape

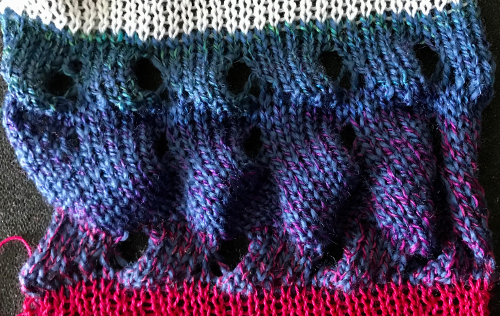

Lastly, a swatch ending in all knit rows. The only remaining issue is the fact that those side triangles are formed by stitches that are looser than across the rest of the piece. This yarn is thin and a poor choice, but fine for getting the technique down and beginning to understand what happens to stitches, how one needs to move from one side to the other, and what happens along the edges of each individual shape  In switching to a thicker, space-dyed yarn, the effect is lost to a degree because of the length between color changes. This sample begins to address keeping some slits, but the repeat needs further sorting out

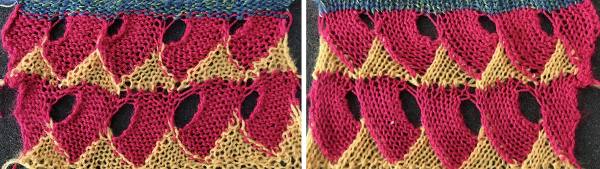

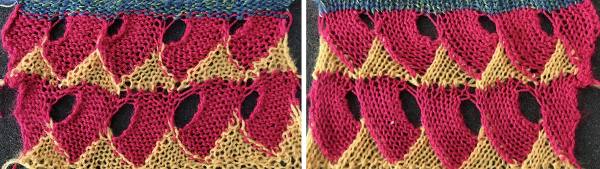

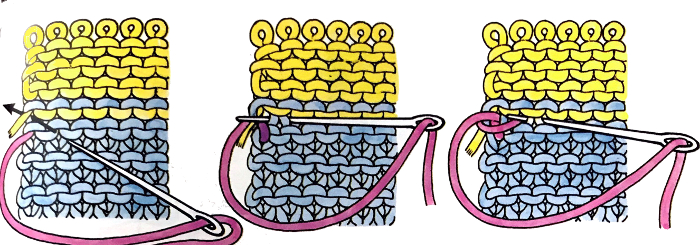

In switching to a thicker, space-dyed yarn, the effect is lost to a degree because of the length between color changes. This sample begins to address keeping some slits, but the repeat needs further sorting out  Following the same idea in visible colors: the yellow wool is another too thin wool (2/20), which makes the edge that will need picking up slow and tedious to deal with because of very small stitches. If I were to make a piece, I would work on the partial shapes in the magenta to make for a smoother color transition start. I used the foundation triangles and row II, with 2 rows of knitting when they were completed to help close the spaces at the top of the eyelets in the magenta. Some striping between repeats at the end of row II is worth considering in alternate colors, for more rows, or even in a thicker yarn.

Following the same idea in visible colors: the yellow wool is another too thin wool (2/20), which makes the edge that will need picking up slow and tedious to deal with because of very small stitches. If I were to make a piece, I would work on the partial shapes in the magenta to make for a smoother color transition start. I used the foundation triangles and row II, with 2 rows of knitting when they were completed to help close the spaces at the top of the eyelets in the magenta. Some striping between repeats at the end of row II is worth considering in alternate colors, for more rows, or even in a thicker yarn.

It is possible to develop shapes, to consider the number of stitches required and whether the fact that other than garter stitch knit stitches are not square,

to consider the number of stitches required and whether the fact that other than garter stitch knit stitches are not square, Then there is the world of making each section /shape as large or as small as desired, shaping them by increasing or decreasing stitches adding and subtracting them as needed by casting on and binding off, partially joining them, knitting and joining them when completed with seam as you knit techniques, changing color within each shape or at the end of every row/section of adjoining ones, working the piece in one color only or using a space dyed yarn for random color patterning. Quilting diagrams can be a boon for inspiration for seam as you knit.

Then there is the world of making each section /shape as large or as small as desired, shaping them by increasing or decreasing stitches adding and subtracting them as needed by casting on and binding off, partially joining them, knitting and joining them when completed with seam as you knit techniques, changing color within each shape or at the end of every row/section of adjoining ones, working the piece in one color only or using a space dyed yarn for random color patterning. Quilting diagrams can be a boon for inspiration for seam as you knit.

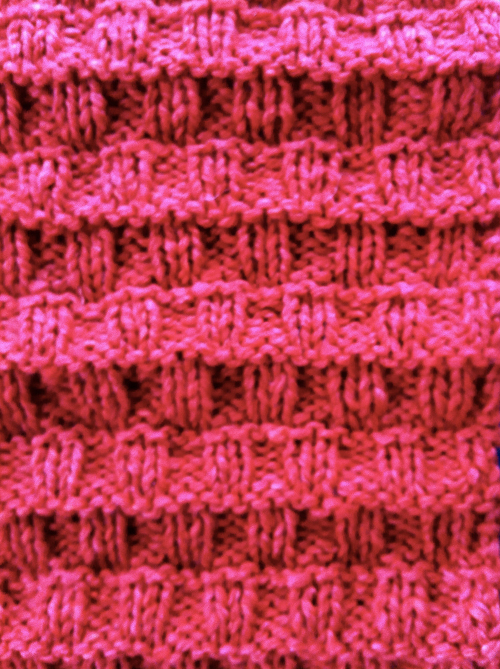

I found this on Pinterest, it strikes me as masterful use of related techniques

Lots of hand-knit inspiration and free patterns: https://intheloopknitting.com/entrelac-knitting-patterns/#freepatterns

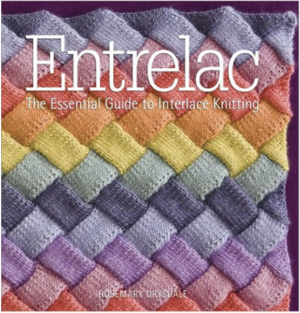

This book explores the technique to the max Some of its swatch images are shared in this review of it , there is also a sequel

Some of its swatch images are shared in this review of it , there is also a sequel

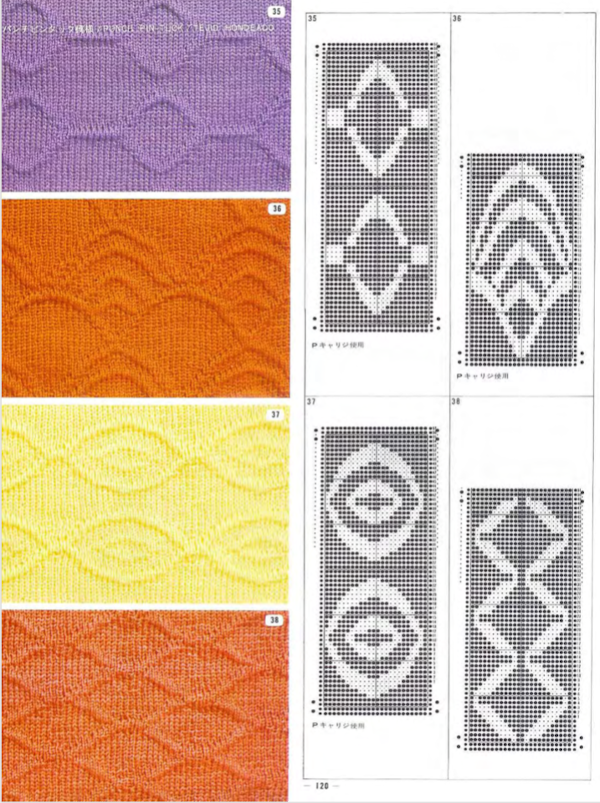

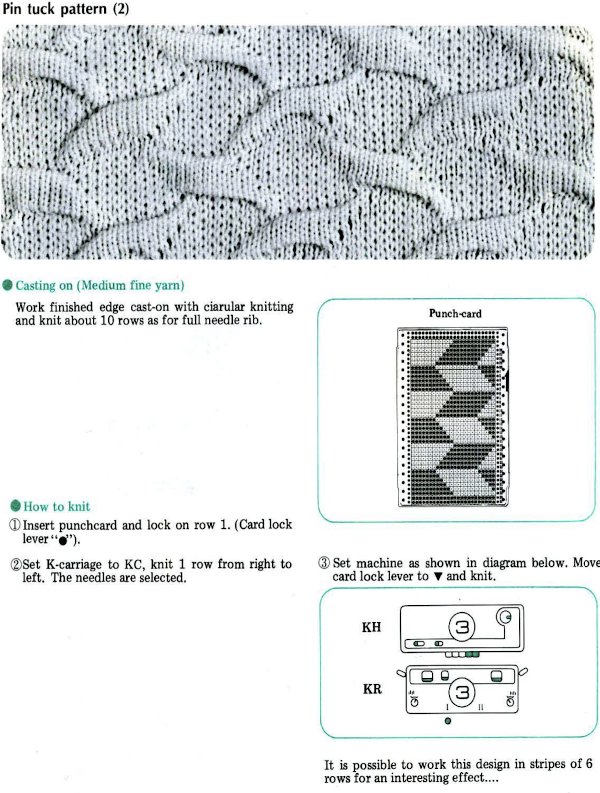

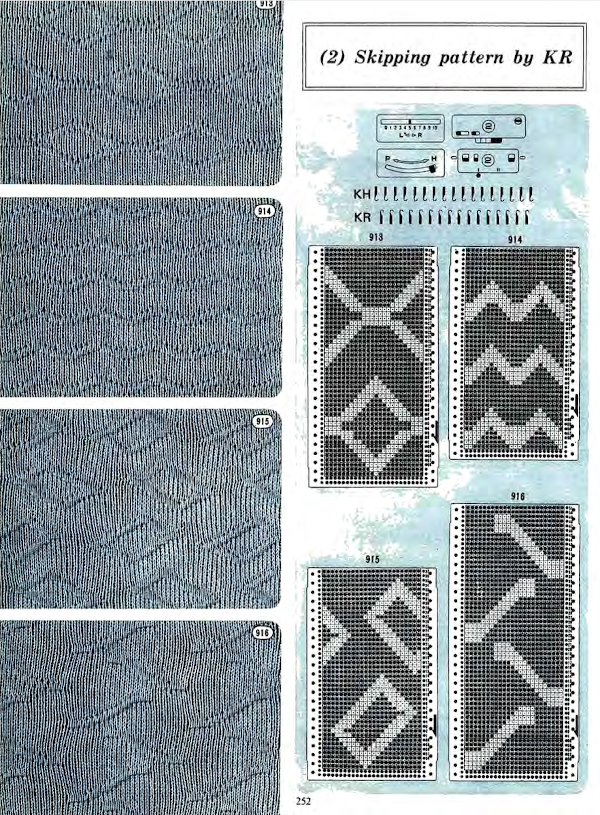

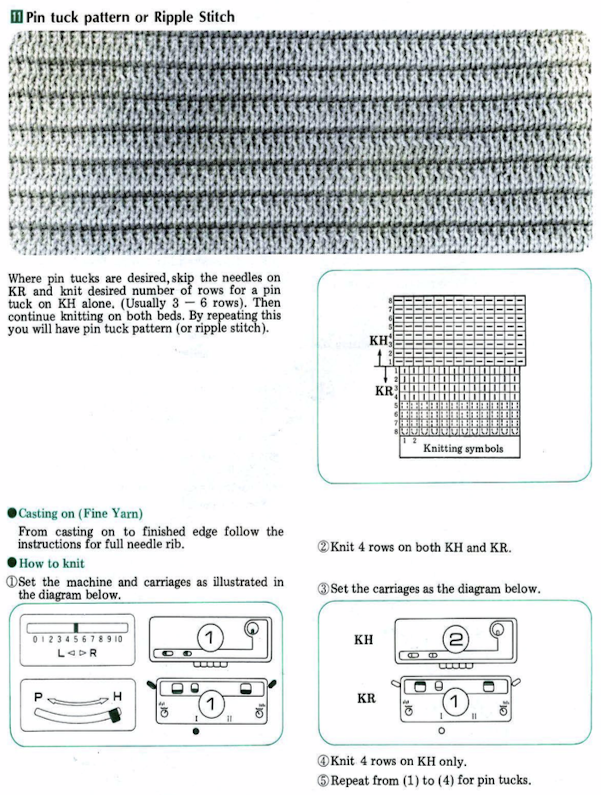

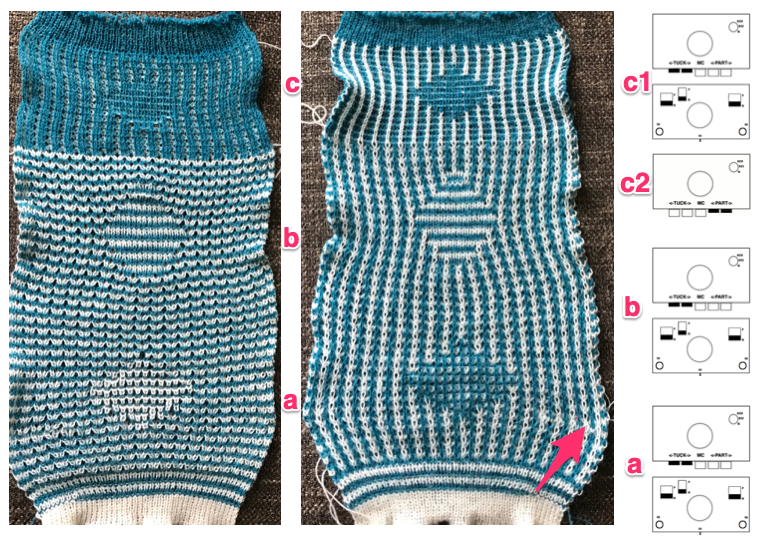

Three slip stitch entrelac pretenders using slip stitch patterning and holding

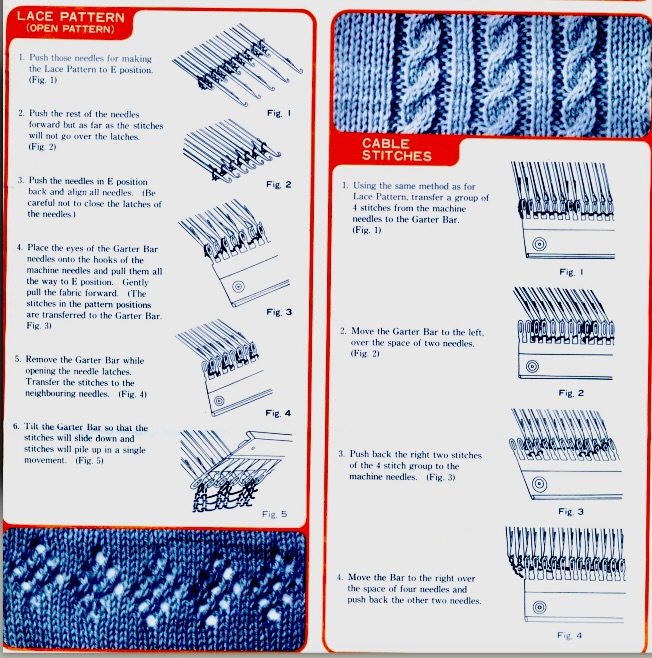

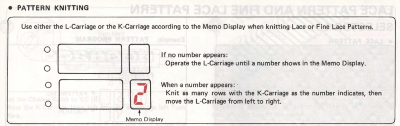

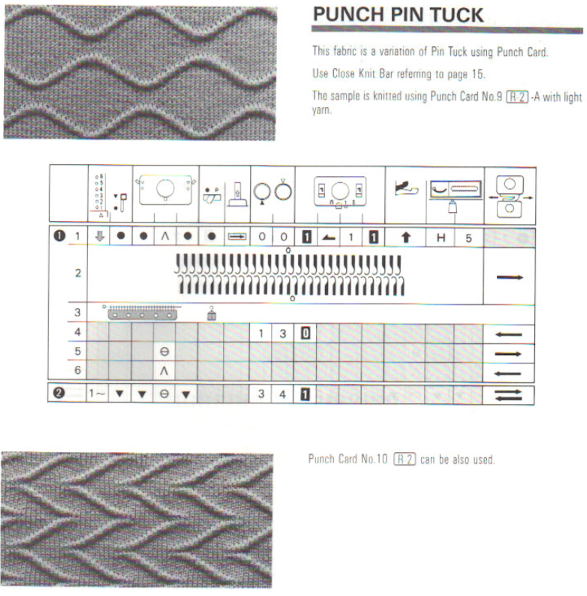

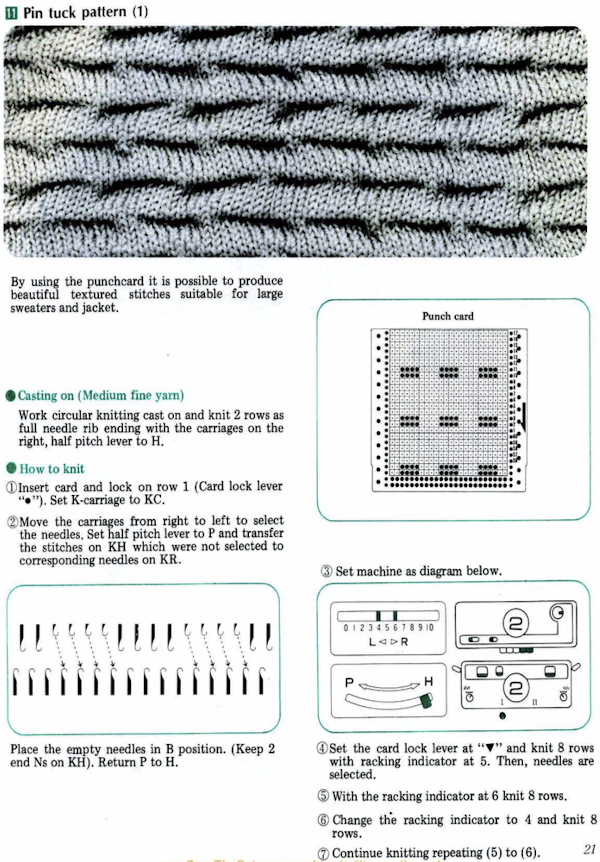

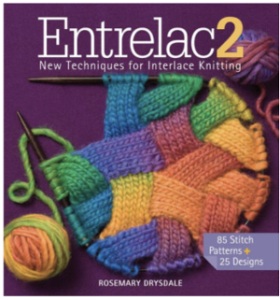

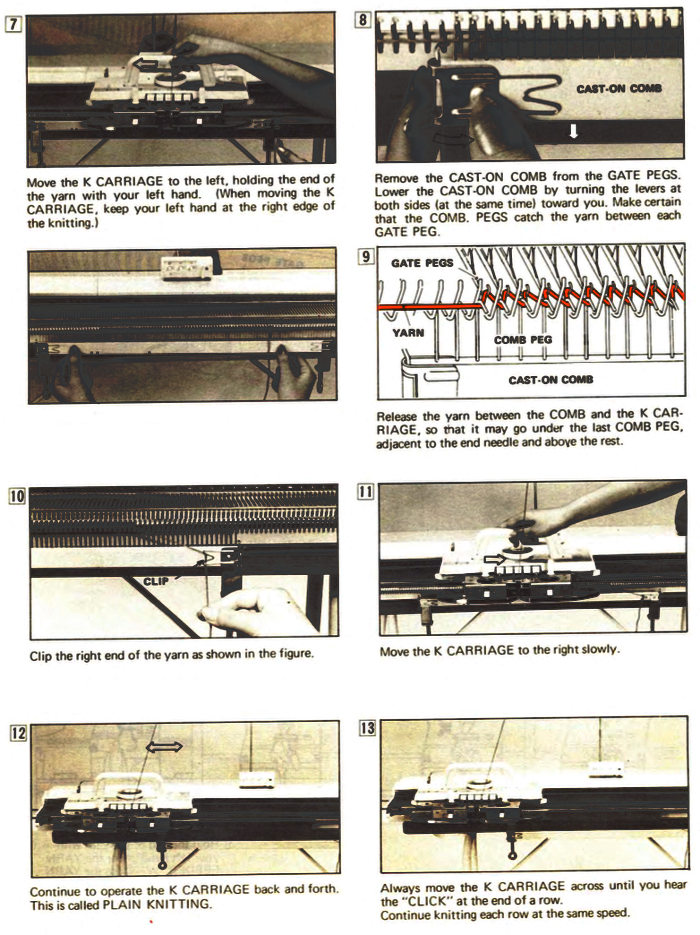

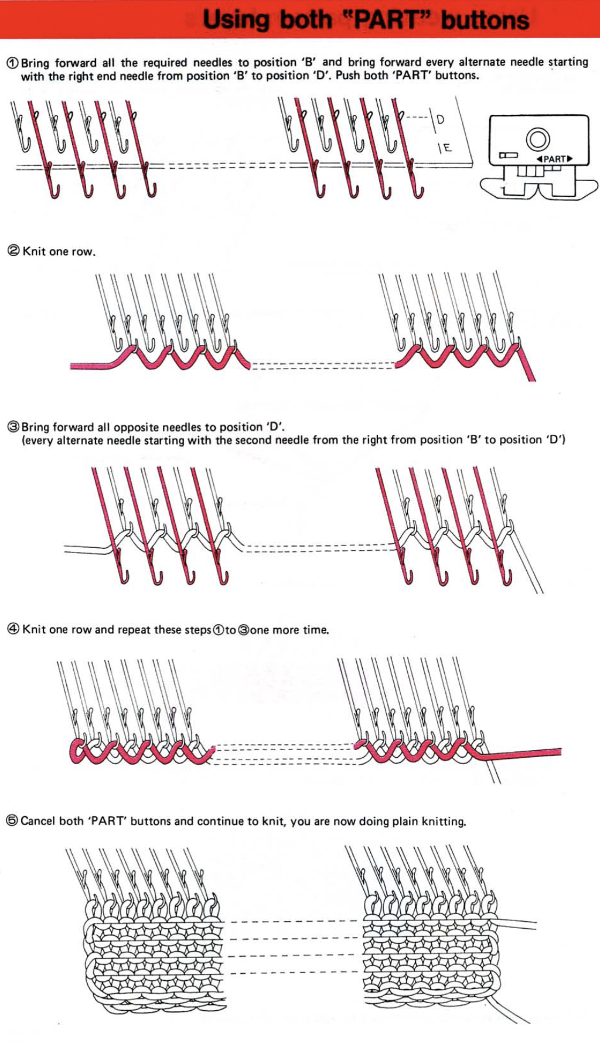

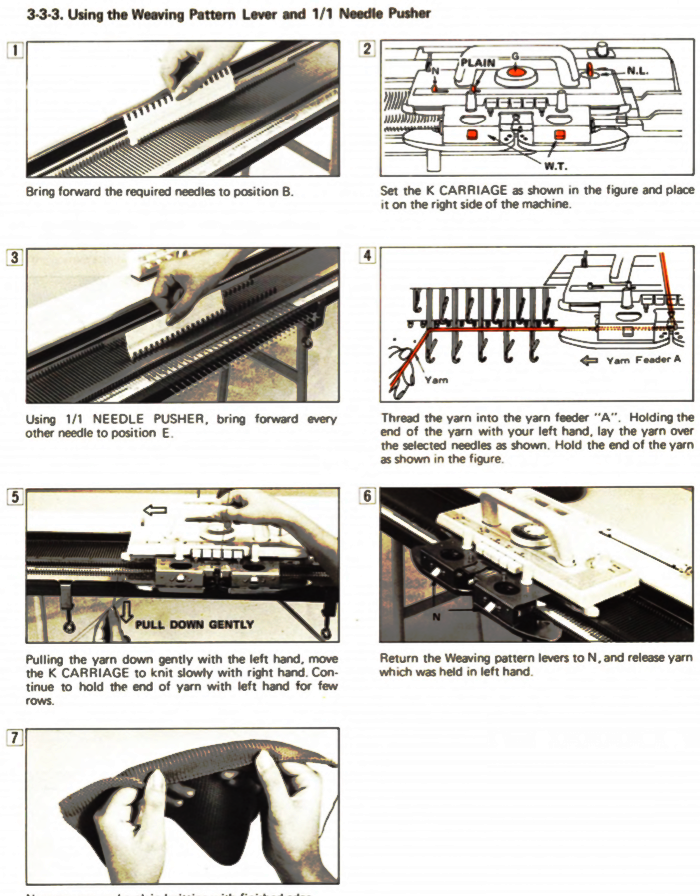

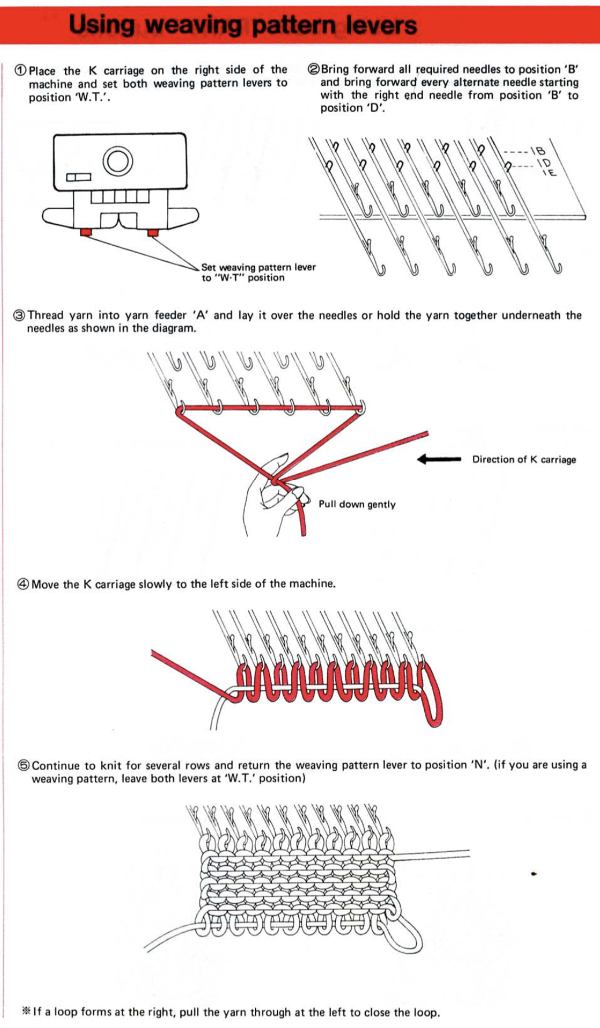

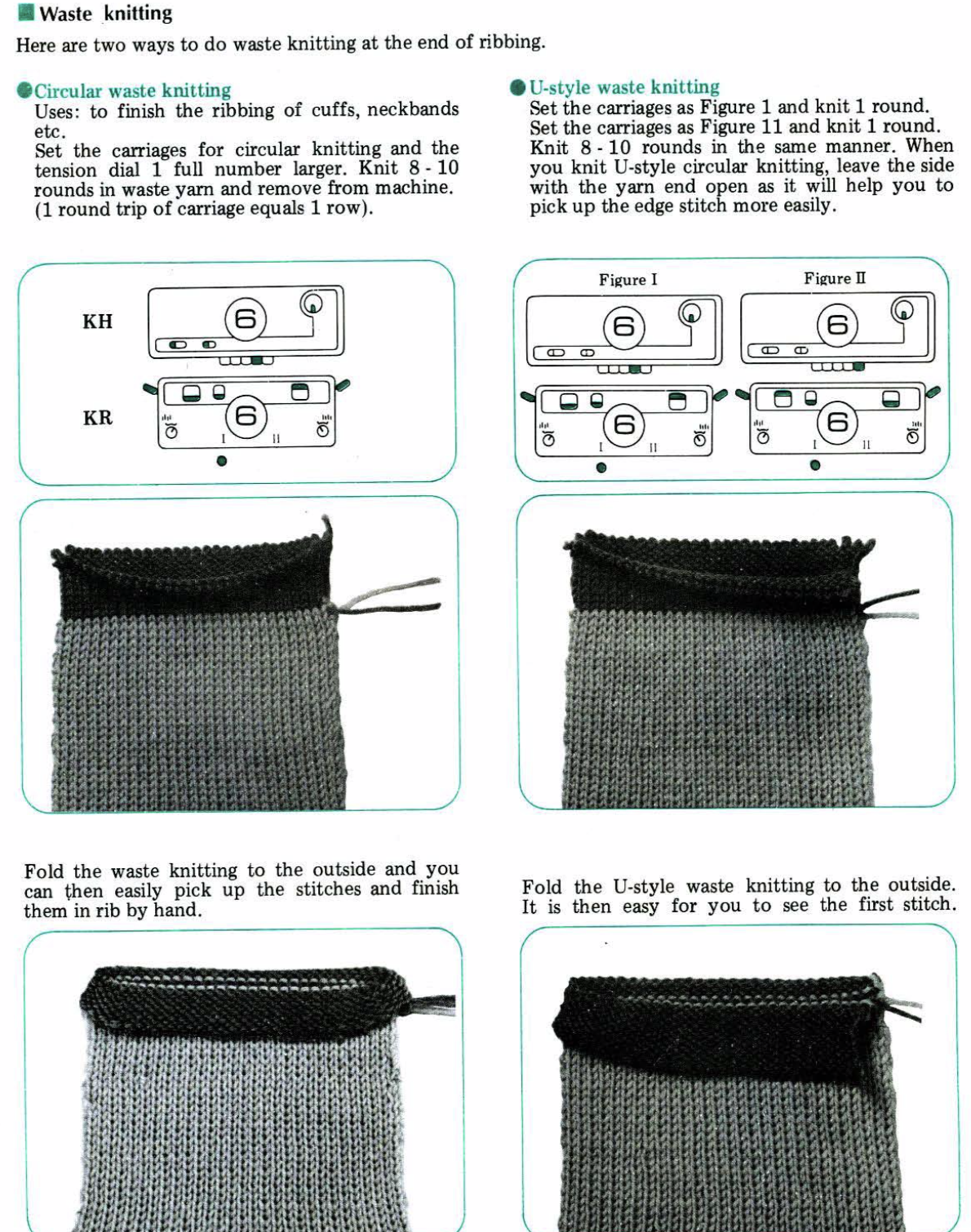

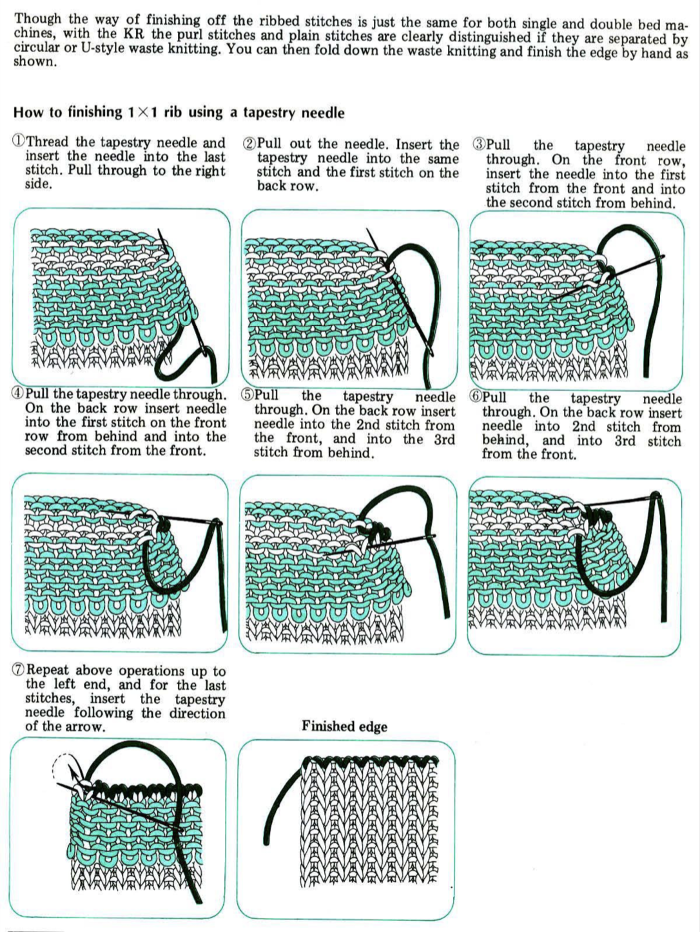

from the Brother Ribber techniques book

from the Brother Ribber techniques book

In blister jacquard more rows are also worked on the main bed than on the ribber, creating a fabric with at times high textured. It may be executed in 2 colors as well. A “normal” DBJ card can be used, but the ribber carriage settings need to be changed with each color change. Things become far easier if the fabric is color separated for the technique and the original design is modified. Color variations merit their own posts

In blister jacquard more rows are also worked on the main bed than on the ribber, creating a fabric with at times high textured. It may be executed in 2 colors as well. A “normal” DBJ card can be used, but the ribber carriage settings need to be changed with each color change. Things become far easier if the fabric is color separated for the technique and the original design is modified. Color variations merit their own posts

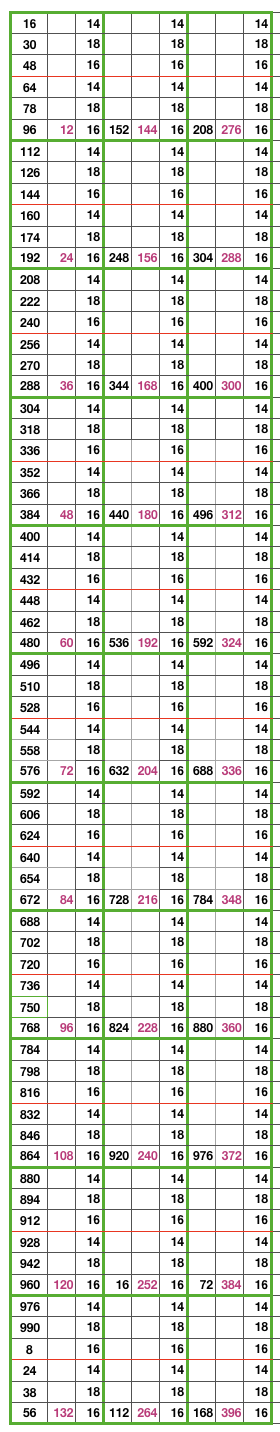

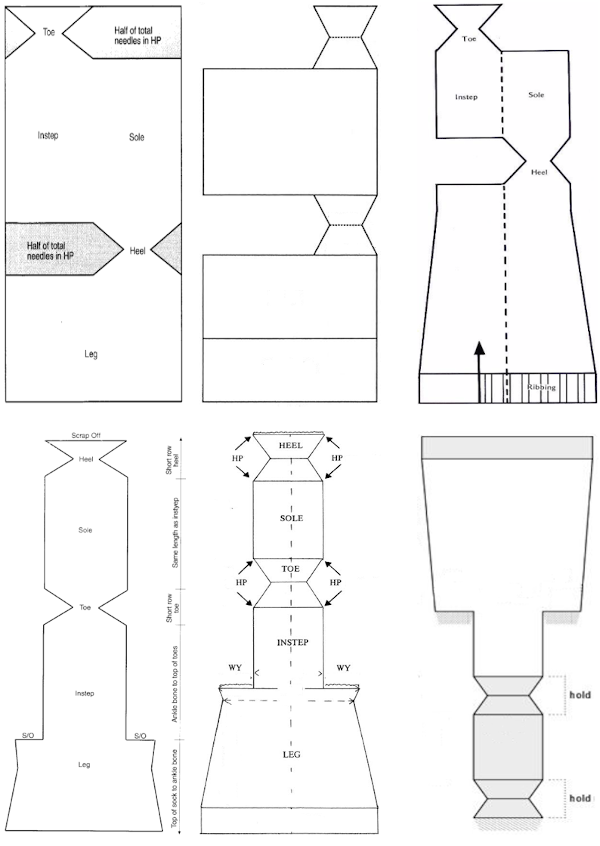

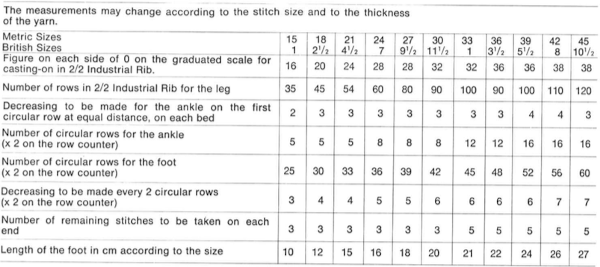

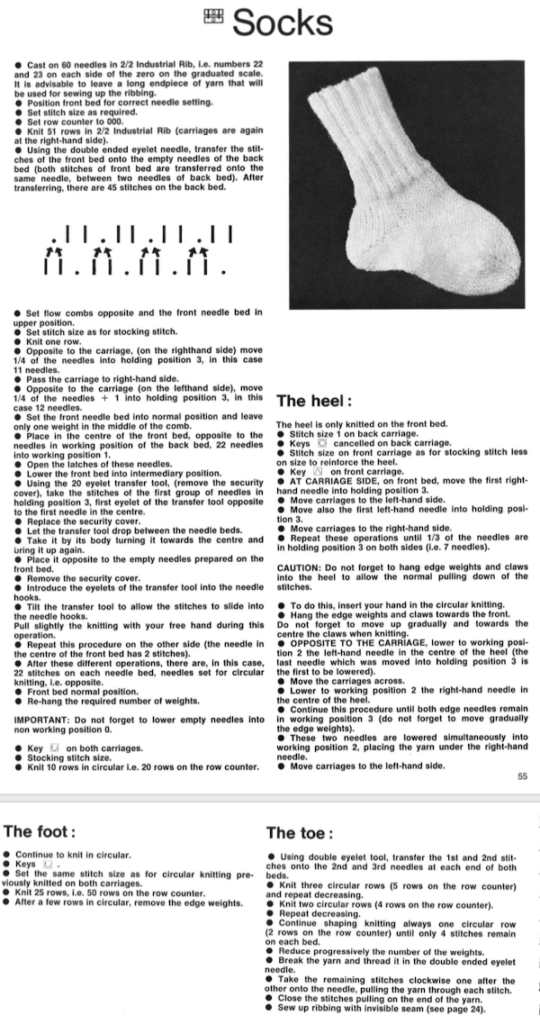

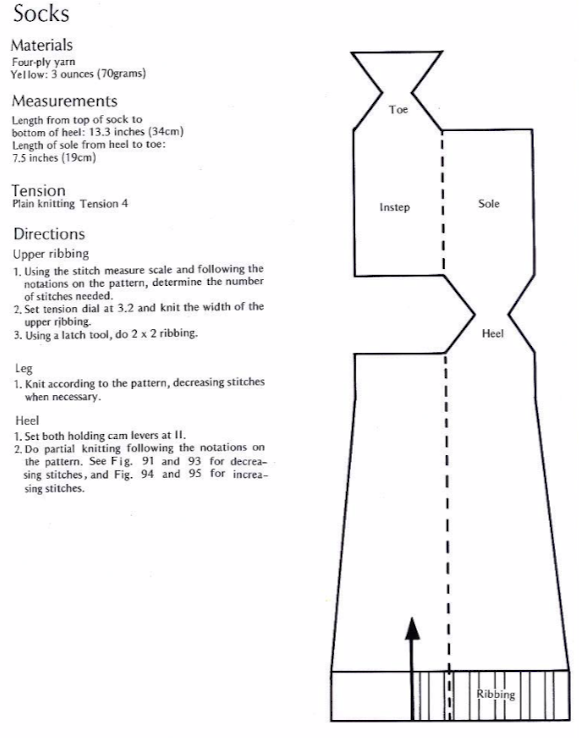

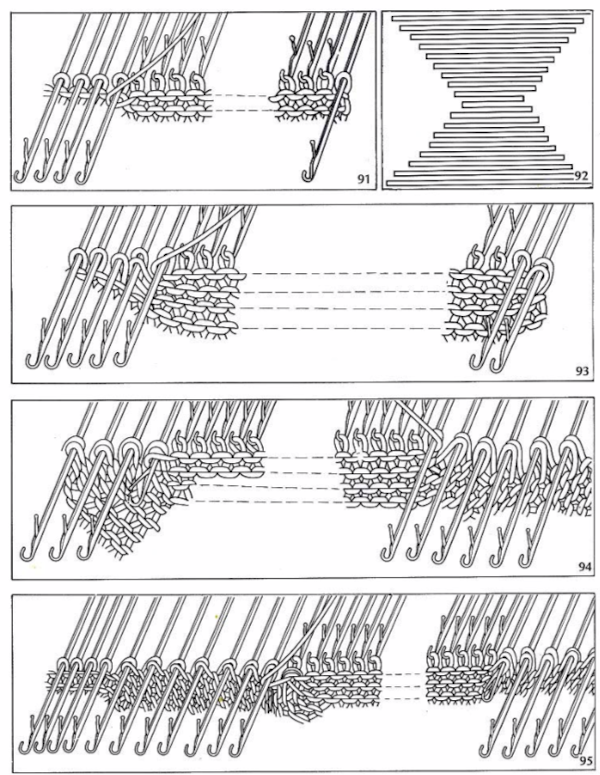

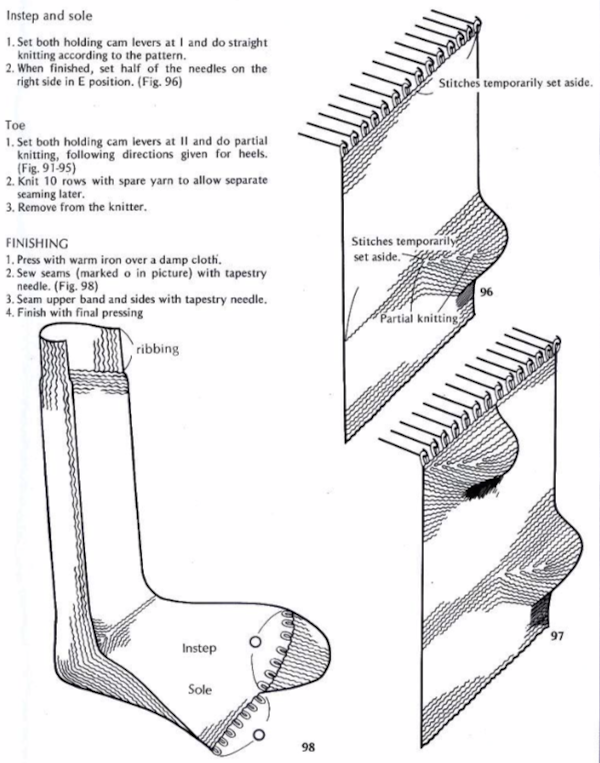

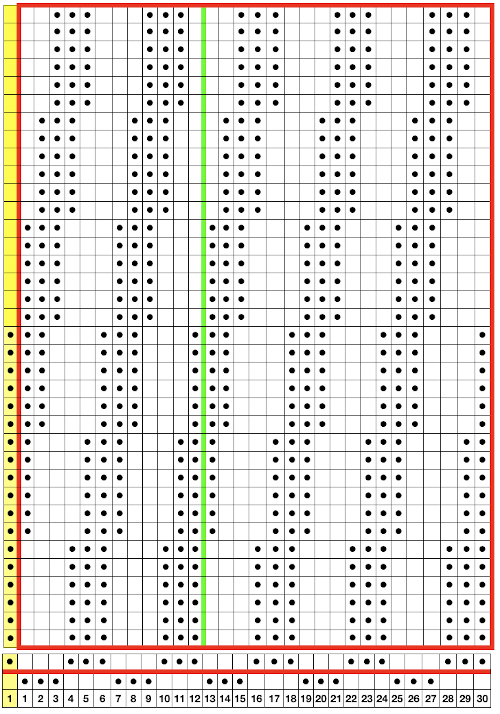

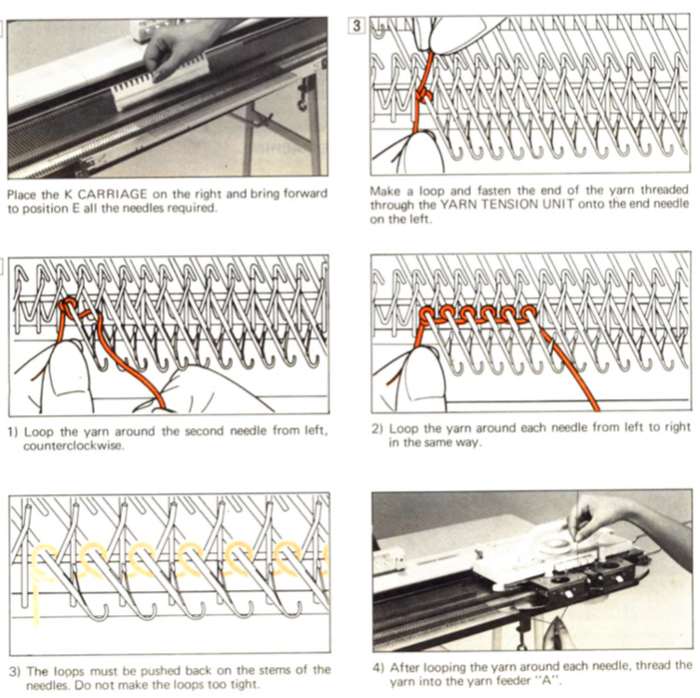

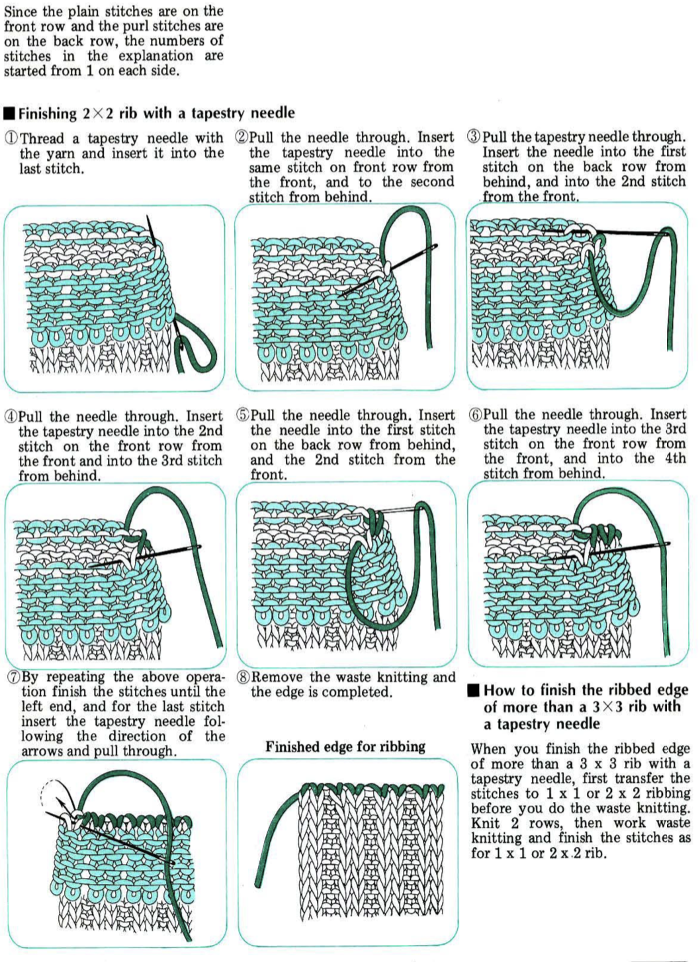

Patterns from manufacturers: Superba manual

Patterns from manufacturers: Superba manual

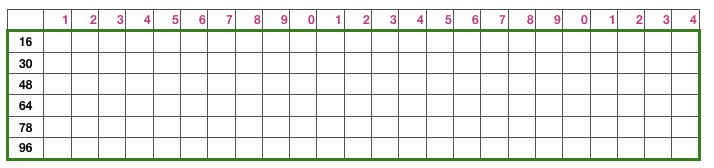

on page 38 a repeat and instructions are offered for a spiral tube sock. The latter has no heel shaping, but traditional toe shaping can be added.

on page 38 a repeat and instructions are offered for a spiral tube sock. The latter has no heel shaping, but traditional toe shaping can be added.

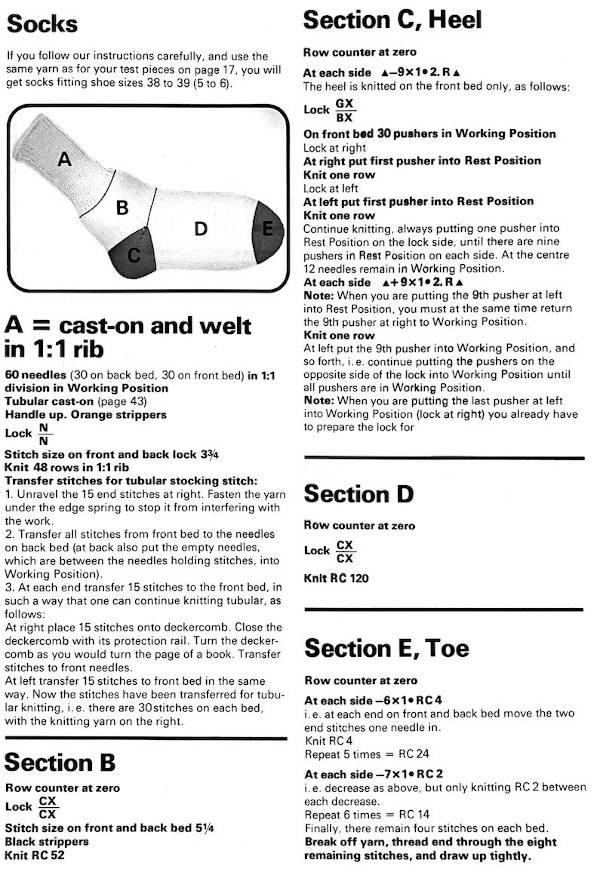

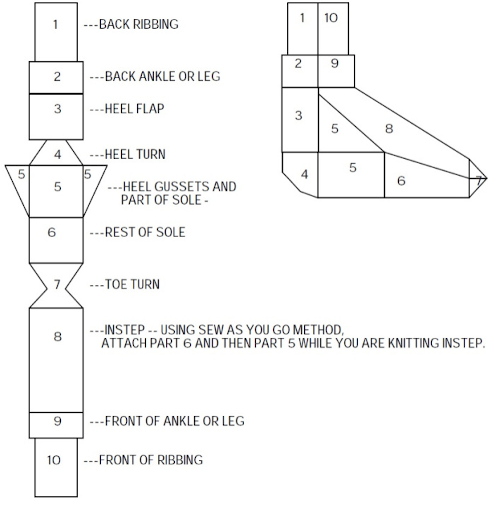

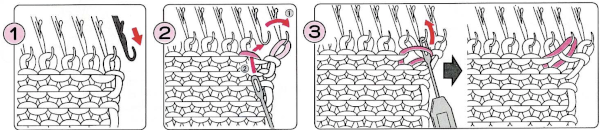

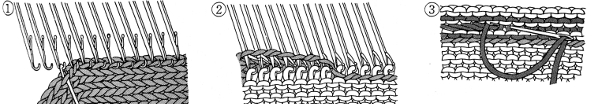

Lastly, it is possible to knit socks sideways (as well as gloves), usually in garter stitch and in hand knitting. This is a crochet illustration that points to the general construction method.

Lastly, it is possible to knit socks sideways (as well as gloves), usually in garter stitch and in hand knitting. This is a crochet illustration that points to the general construction method.

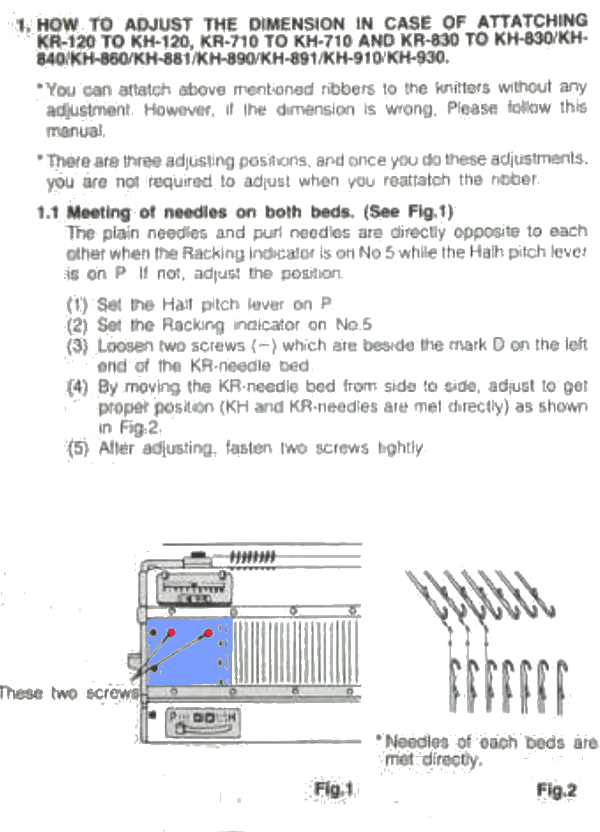

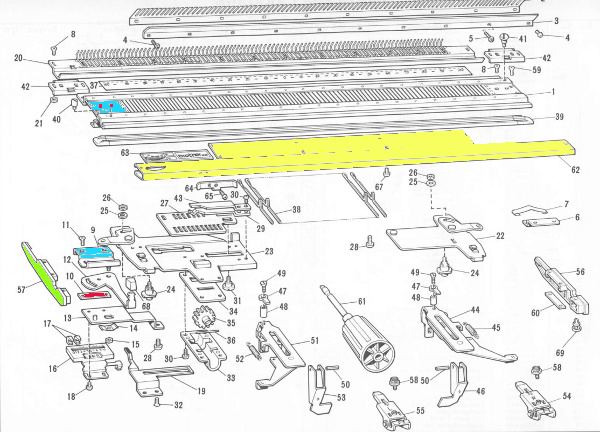

I asked on Ravelry for advice or shared experiences. A possible culprit was suggested to me, and I was pointed toward the

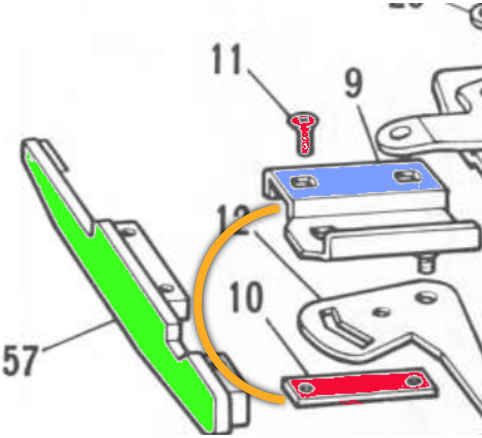

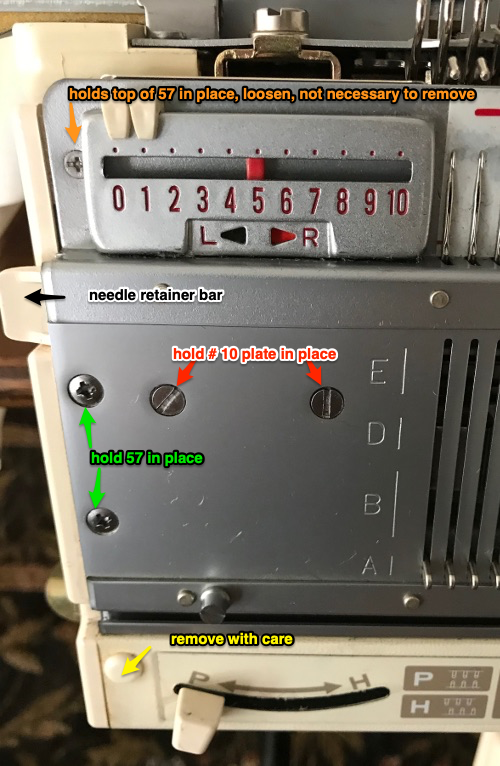

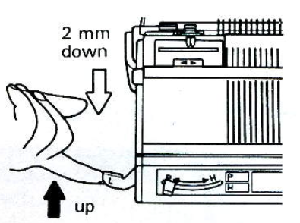

I asked on Ravelry for advice or shared experiences. A possible culprit was suggested to me, and I was pointed toward the When I tried to turn the screws marked in red I found they were loose. After I took apart the racking handle, braving far more disassembly than turned out to be needed, housing little screws and washers in separate small plastic containers along with their comrade larger parts, I found perhaps I could have reduced the effort considerably. I did not take photos during the process, as I was not brimming with confidence in the result. Enlarging a portion of the above helped me understand how parts related to each other a bit better.

When I tried to turn the screws marked in red I found they were loose. After I took apart the racking handle, braving far more disassembly than turned out to be needed, housing little screws and washers in separate small plastic containers along with their comrade larger parts, I found perhaps I could have reduced the effort considerably. I did not take photos during the process, as I was not brimming with confidence in the result. Enlarging a portion of the above helped me understand how parts related to each other a bit better.

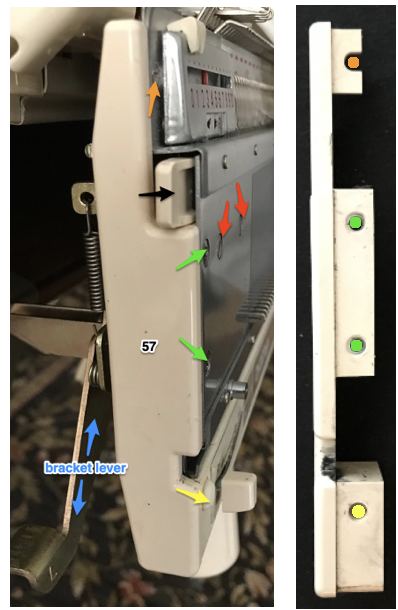

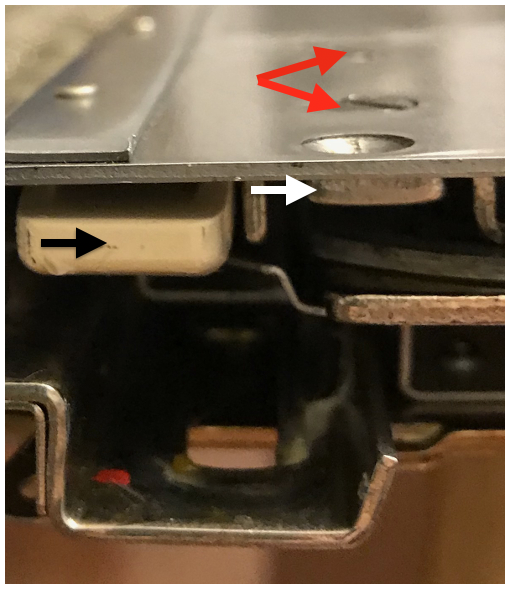

It really may not have been necessary to even remove the bracket lever. The #10 piece of metal was loose inside the machine, might simply have fallen out if I had turned the bed on its side and given it a mild shake after removing #57. This is with the piece in question in its housing where it belongs (white arrow), shown in relation to the needle retainer bar (black arrow) and screws marked with red arrows that hold it in place.

It really may not have been necessary to even remove the bracket lever. The #10 piece of metal was loose inside the machine, might simply have fallen out if I had turned the bed on its side and given it a mild shake after removing #57. This is with the piece in question in its housing where it belongs (white arrow), shown in relation to the needle retainer bar (black arrow) and screws marked with red arrows that hold it in place.  The piece is obviously thinner than the space it lives in, so for screws to anchor it properly, a flathead screwdriver or other improvised tool needs to be inserted under it, lifting it into position and holding it in place with its holes lined up with outside of bed so screws can grip it and be tightened properly.

The piece is obviously thinner than the space it lives in, so for screws to anchor it properly, a flathead screwdriver or other improvised tool needs to be inserted under it, lifting it into position and holding it in place with its holes lined up with outside of bed so screws can grip it and be tightened properly.

a rearview with ends woven in

a rearview with ends woven in

When the end of the first row that row is reached, as contrast color is added, stitches need to be cast on on the far left in order to keep the work on the bed a constant number of stitches. The usual method suggested is e wrapping, this is picking up from the row below. I found either method produced looser, longer stitches on the far edge

When the end of the first row that row is reached, as contrast color is added, stitches need to be cast on on the far left in order to keep the work on the bed a constant number of stitches. The usual method suggested is e wrapping, this is picking up from the row below. I found either method produced looser, longer stitches on the far edge

reaching the far right:

reaching the far right:

It does a good job of weighing down those straight edges along the bumps, making the stitches easier to pick up. When rehanging those stitches, uniformly hanging the loops, not the knots along the edges involved will give a smoother join. Here a paper clip is used as the “hanger”

It does a good job of weighing down those straight edges along the bumps, making the stitches easier to pick up. When rehanging those stitches, uniformly hanging the loops, not the knots along the edges involved will give a smoother join. Here a paper clip is used as the “hanger”

Lastly, a swatch ending in all knit rows. The only remaining issue is the fact that those side triangles are formed by stitches that are looser than across the rest of the piece. This yarn is thin and a poor choice, but fine for getting the technique down and beginning to understand what happens to stitches, how one needs to move from one side to the other, and what happens along the edges of each individual shape

Lastly, a swatch ending in all knit rows. The only remaining issue is the fact that those side triangles are formed by stitches that are looser than across the rest of the piece. This yarn is thin and a poor choice, but fine for getting the technique down and beginning to understand what happens to stitches, how one needs to move from one side to the other, and what happens along the edges of each individual shape

to consider the number of stitches required and whether the fact that other than garter stitch knit stitches are not square,

to consider the number of stitches required and whether the fact that other than garter stitch knit stitches are not square,

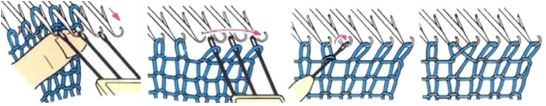

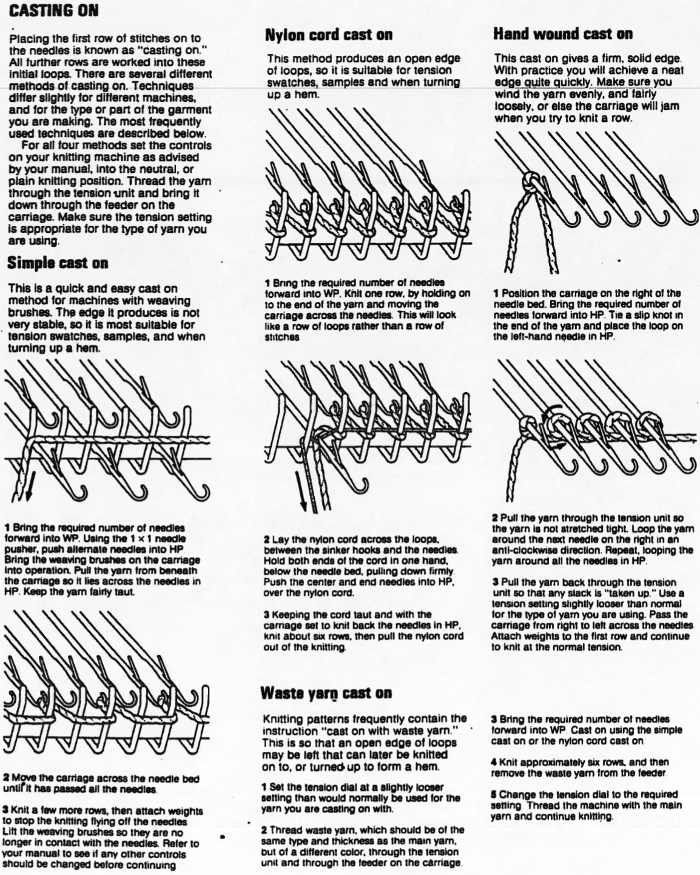

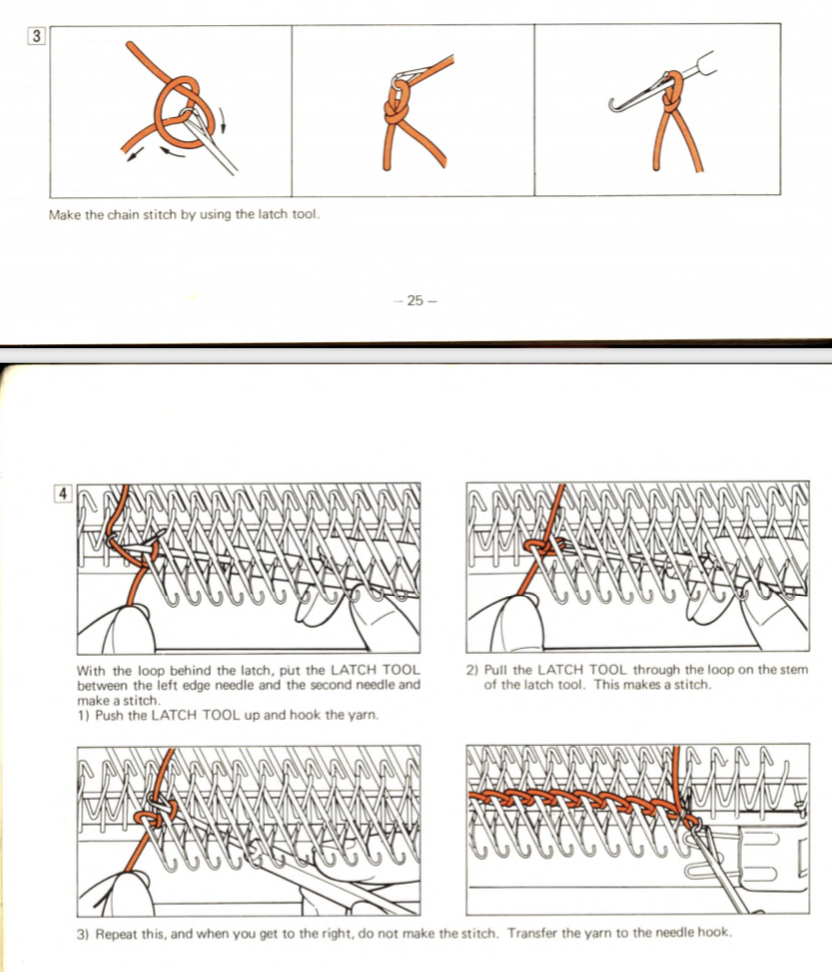

Weaving cast-on only works on machines with weaving brushes ie Brother. I tend to knit with weaving brushes down no matter what the fabric is unless using them results in problems ie the particular yarn being used has a tendency to get caught up in them.

Weaving cast-on only works on machines with weaving brushes ie Brother. I tend to knit with weaving brushes down no matter what the fabric is unless using them results in problems ie the particular yarn being used has a tendency to get caught up in them.

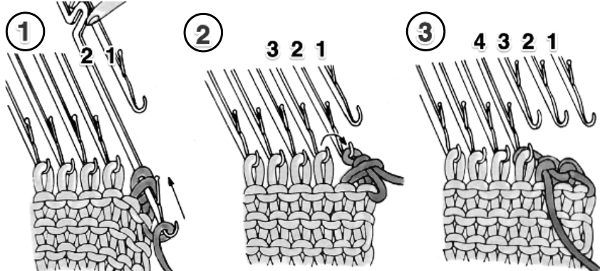

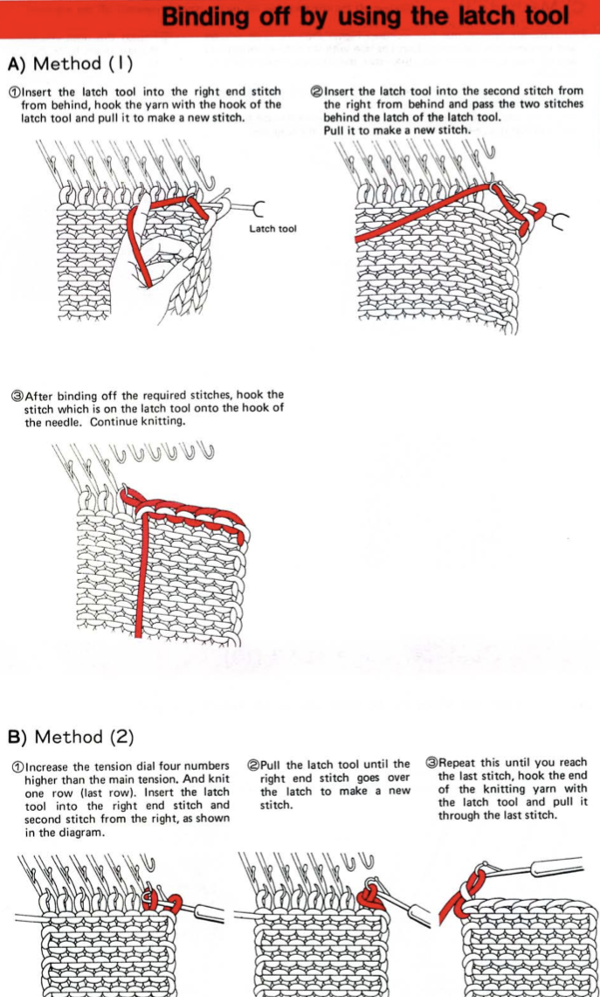

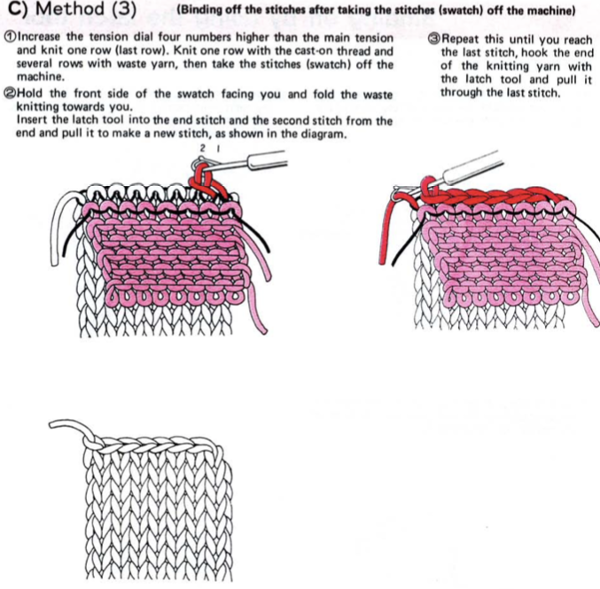

A crochet hook could be used in place of the latch tool.

A crochet hook could be used in place of the latch tool.

For mock rib executed on the single bed, for double rib as well, see

For mock rib executed on the single bed, for double rib as well, see

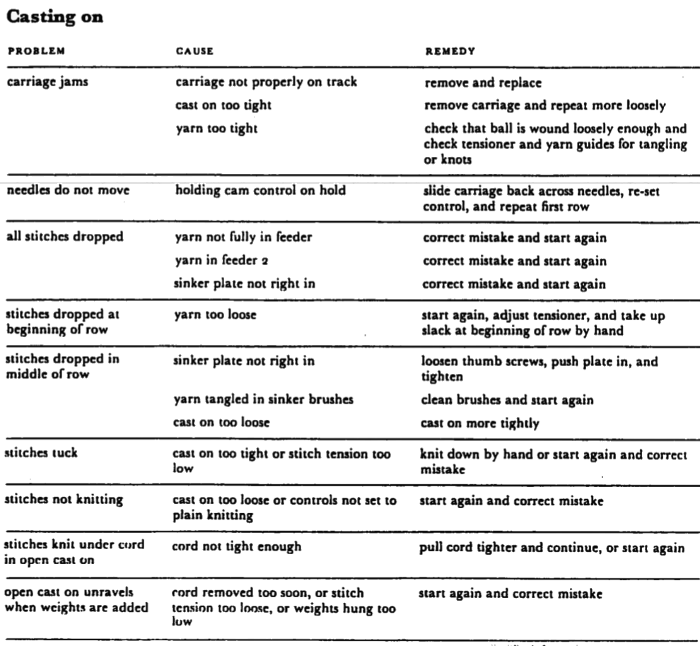

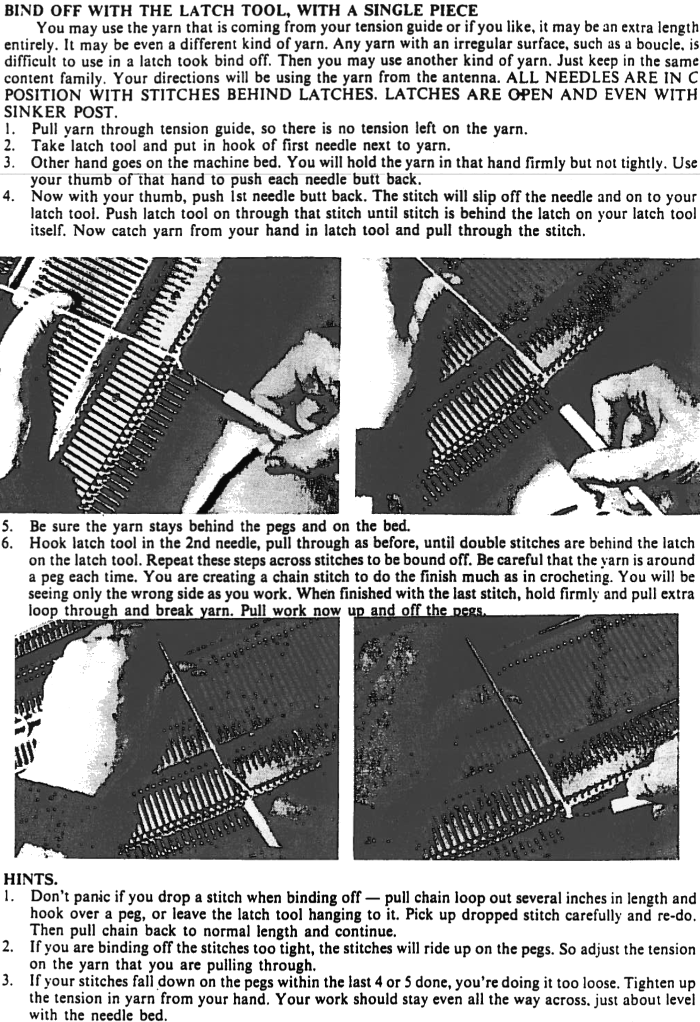

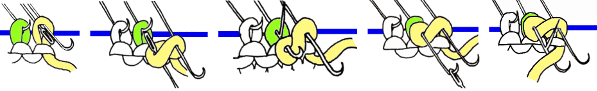

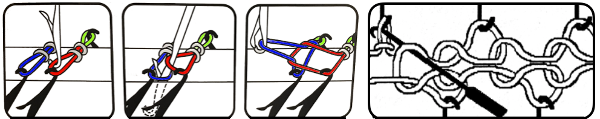

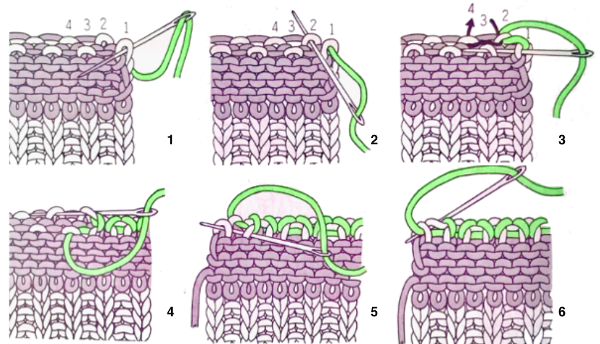

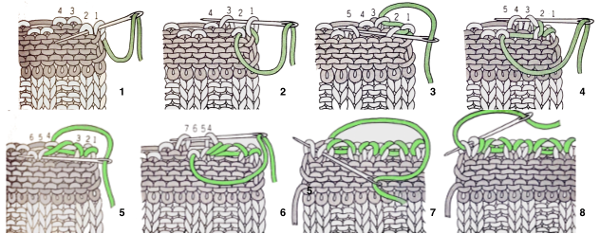

Reviewing approaches to binding off with needle and yarn: working single bed is sometimes performed on the machine and is illustrated below working from left to right. It is referred to as back or stem stitch and “sew off” method, and is shared in many of the old machine knitting manuals. It is easier to achieve if after knitting the last row one knits at least 2 or 3 more rows in waste yarn to make the stitches more accessible. The knit side shows single loops in view upon completion. Dropping small groups of stitches off as one makes progress across the row may make the technique easier, helping with the placement of the other hand to hold the work. On the machine, the fixed distances between needles and gate pegs help to keep the tension even. The backstitching may be done off the machine, but maintaining even tension there may be a bit harder.

Reviewing approaches to binding off with needle and yarn: working single bed is sometimes performed on the machine and is illustrated below working from left to right. It is referred to as back or stem stitch and “sew off” method, and is shared in many of the old machine knitting manuals. It is easier to achieve if after knitting the last row one knits at least 2 or 3 more rows in waste yarn to make the stitches more accessible. The knit side shows single loops in view upon completion. Dropping small groups of stitches off as one makes progress across the row may make the technique easier, helping with the placement of the other hand to hold the work. On the machine, the fixed distances between needles and gate pegs help to keep the tension even. The backstitching may be done off the machine, but maintaining even tension there may be a bit harder.

or the needle and yarn sewing method may be used. There is a limit as to the length of yarn used so as not to pose problems. Very wide pieces may prove to be a challenge, requiring more than a single yarn end to complete the bind-off. My own yarn end max limit for sewing up or off is about 18 inches

or the needle and yarn sewing method may be used. There is a limit as to the length of yarn used so as not to pose problems. Very wide pieces may prove to be a challenge, requiring more than a single yarn end to complete the bind-off. My own yarn end max limit for sewing up or off is about 18 inches

I prefer an alternative method for waste yarn scrap off, ending in place of circular or U knitting: knit the last row in garment yarn. Thread up waste yarn, and knit it at single-bed tension. Knit 4 rows on one bed, with a separate strand or even a second contrasting color of equal weight, and knit 4 rows on the opposite bed. Repeat alternating until there are more than 12 rows on each bed and scrap off. This will allow you to press the waste knitting only, and the flaps are opened up to reveal the tops of the stitches created on each bed. Finishing can then be executed as below.

I prefer an alternative method for waste yarn scrap off, ending in place of circular or U knitting: knit the last row in garment yarn. Thread up waste yarn, and knit it at single-bed tension. Knit 4 rows on one bed, with a separate strand or even a second contrasting color of equal weight, and knit 4 rows on the opposite bed. Repeat alternating until there are more than 12 rows on each bed and scrap off. This will allow you to press the waste knitting only, and the flaps are opened up to reveal the tops of the stitches created on each bed. Finishing can then be executed as below.

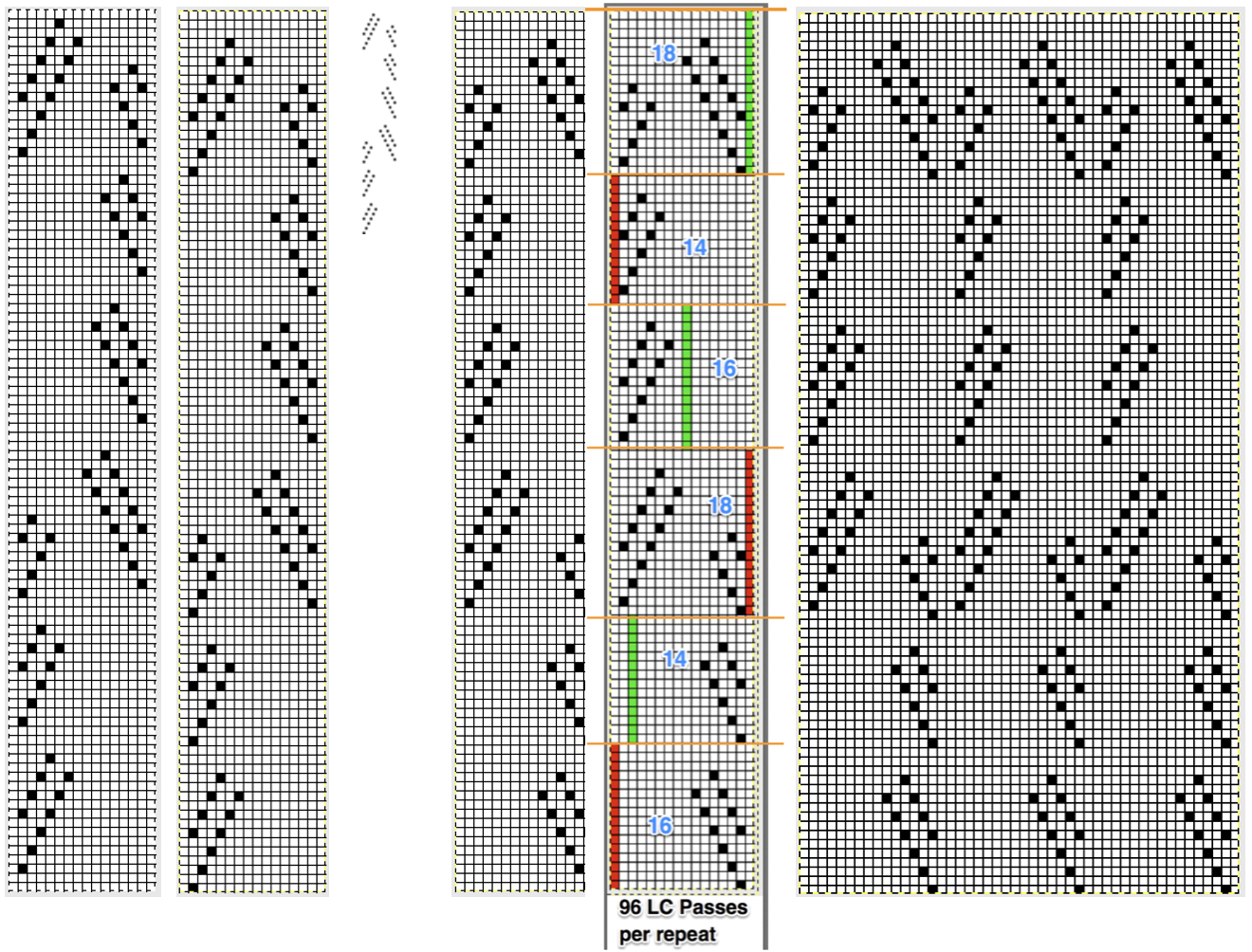

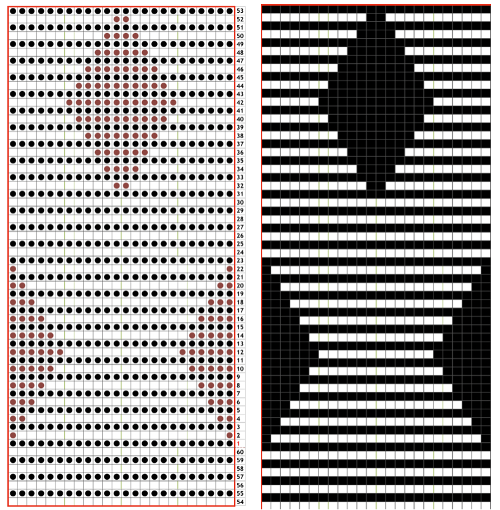

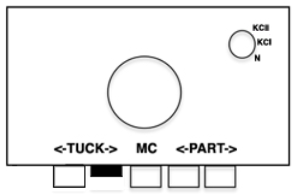

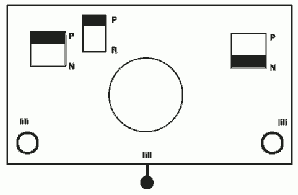

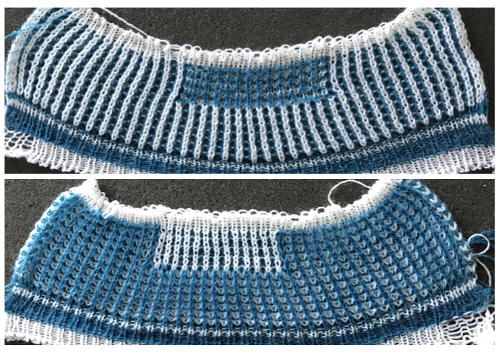

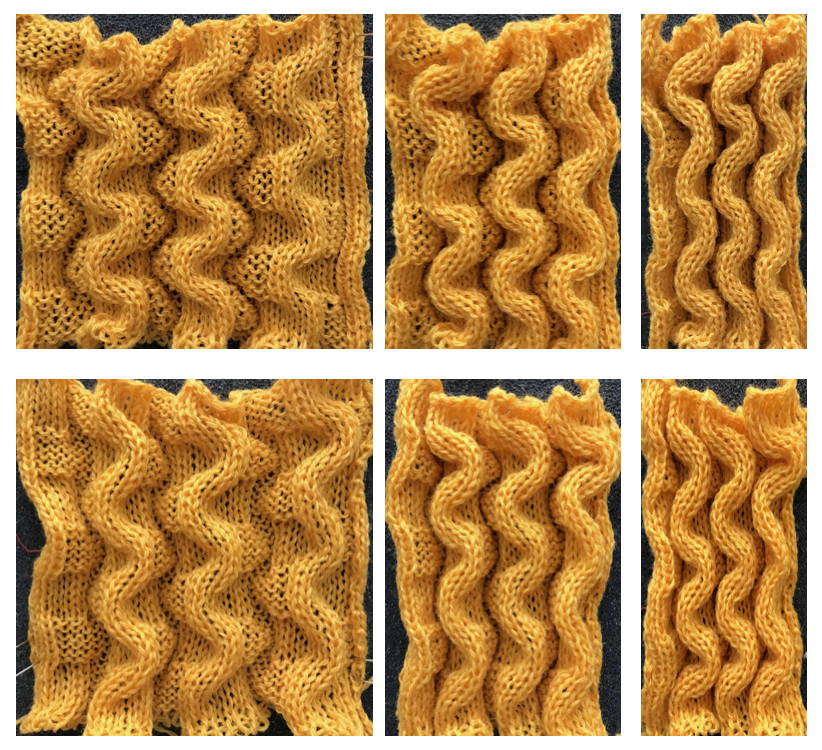

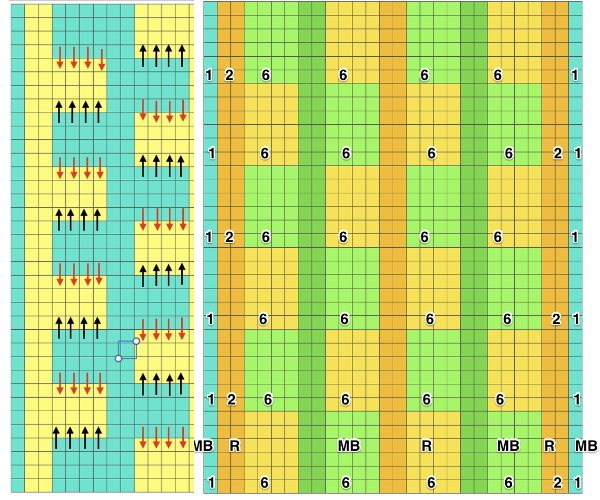

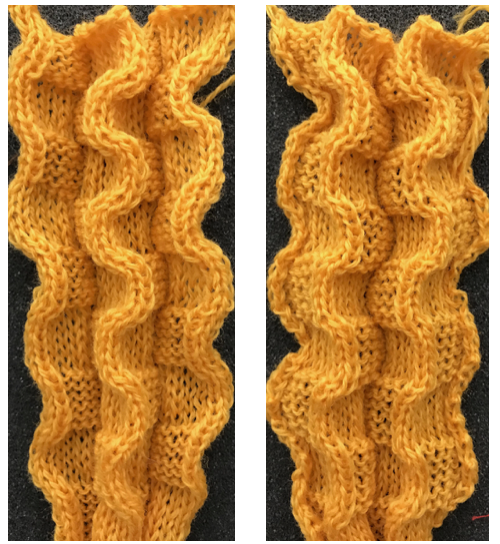

Back to the original method used in the previous post where ribber settings are changed from knit to tuck <– –> every 2 rows along with color changes. I chose a design that would make it easy to identify the location of non-selected needles on the main bed in rows where the ribber will be set to tuck in both directions. The result is interesting, but the solid areas, narrower than the remaining knit, are in the opposite color to the dominant one on each side, the reverse of the inspiration fabric.

Back to the original method used in the previous post where ribber settings are changed from knit to tuck <– –> every 2 rows along with color changes. I chose a design that would make it easy to identify the location of non-selected needles on the main bed in rows where the ribber will be set to tuck in both directions. The result is interesting, but the solid areas, narrower than the remaining knit, are in the opposite color to the dominant one on each side, the reverse of the inspiration fabric.

The ribber remains set for knitting in both directions throughout, with the main bed set to tuck in both directions.

The ribber remains set for knitting in both directions throughout, with the main bed set to tuck in both directions.

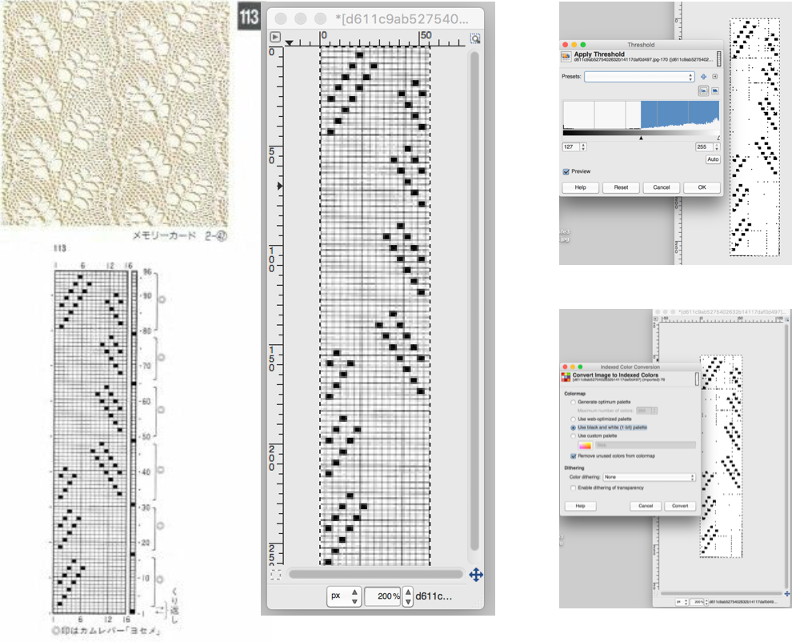

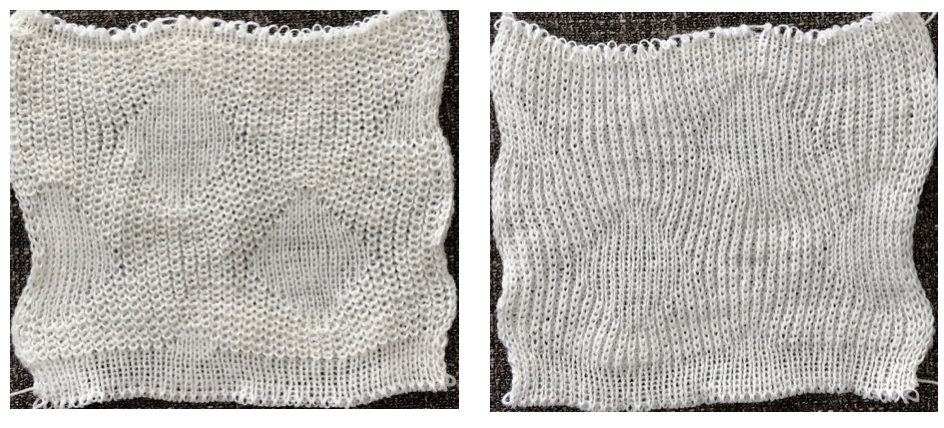

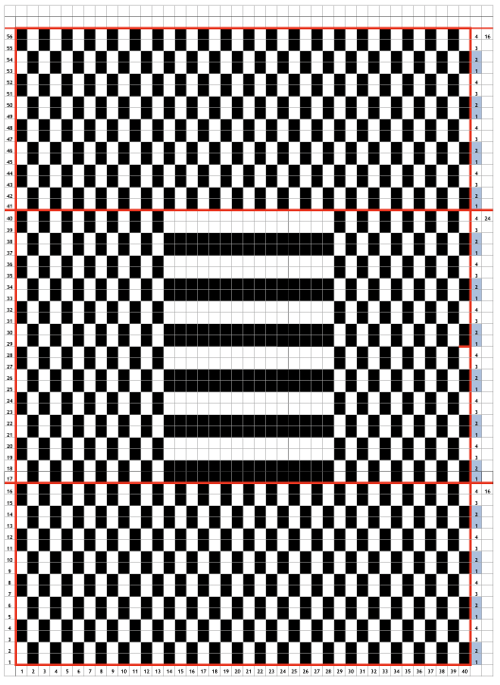

The single 14X84 png

The single 14X84 png

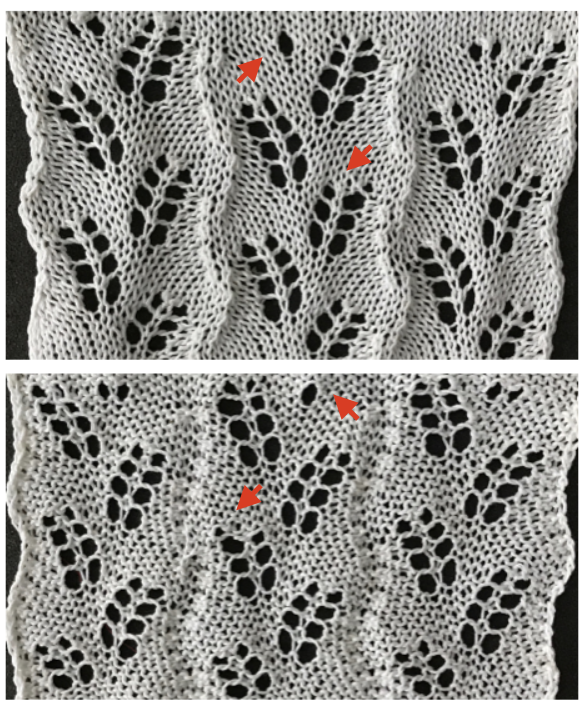

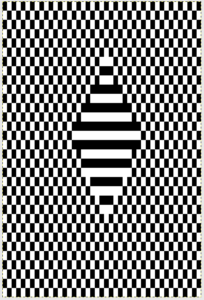

and my small test swatch. The fold on each side and the swing in the pattern appear crisper and better defined to me

and my small test swatch. The fold on each side and the swing in the pattern appear crisper and better defined to me

an attempt at a side view

an attempt at a side view  an earlier

an earlier  Another handknit swatch in worsted weight, perhaps suitable for G carriage

Another handknit swatch in worsted weight, perhaps suitable for G carriage