Fringes are not a personal favorite of mine on machine-knit garments in their “simplest” forms. I can recall using them rarely. Here a cut Passap version was applied to a piece made in my student days, a ruana for which I no longer have the measurements. It was composed of wool DBJ, worked in 10 panels, using a mylar sheet on a 910 for patterning, hand pieced, and is still being worn by its owner.

I made a few items with twisted strands inspired by those seen in wovens produced by my weaving friends. I have no photos of those, failed to document my work for quite a few years. One excuse was the quality of any photos I attempted, and even back in the day, professional photographers charged $180 an hour plus model fees if used. It seemed that adding the cost of such photography to limited edition runs that were planned for sale would make the wholesale price higher than the market would bear. We all make choices based on information we have at that particular time, which was long before the recent easy-to-use photo technology.

I made a few items with twisted strands inspired by those seen in wovens produced by my weaving friends. I have no photos of those, failed to document my work for quite a few years. One excuse was the quality of any photos I attempted, and even back in the day, professional photographers charged $180 an hour plus model fees if used. It seemed that adding the cost of such photography to limited edition runs that were planned for sale would make the wholesale price higher than the market would bear. We all make choices based on information we have at that particular time, which was long before the recent easy-to-use photo technology.

There now is a very good video by Diana Sullivan showing a machine knit version of twisted fringe produced on the machine.

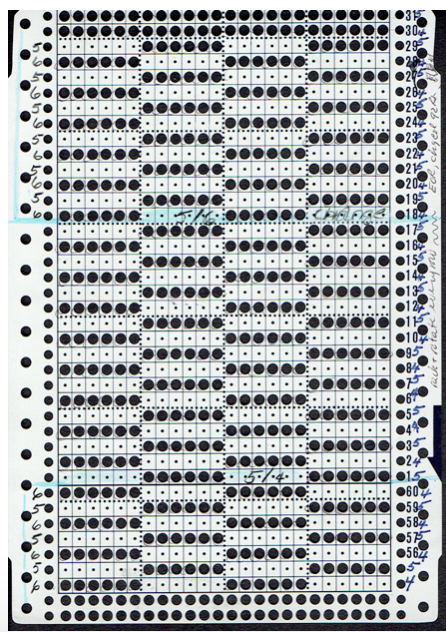

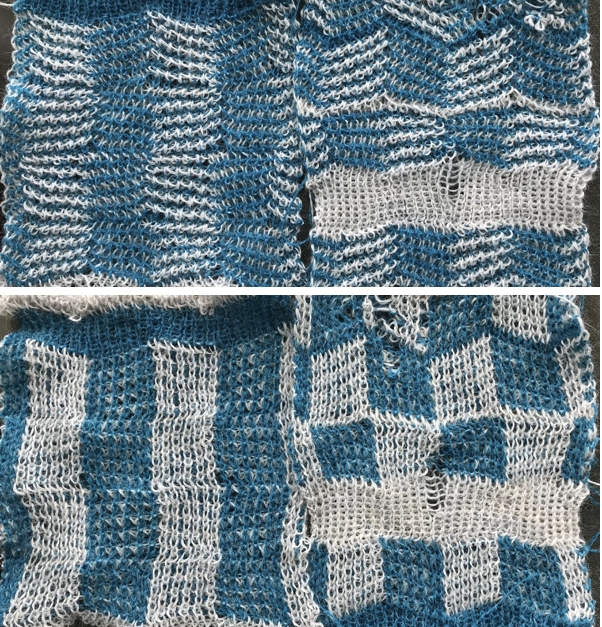

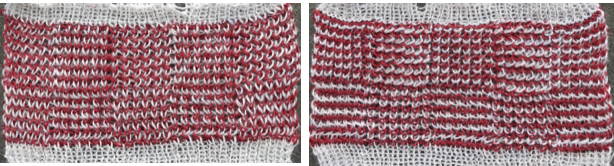

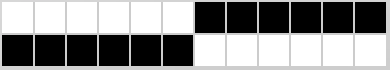

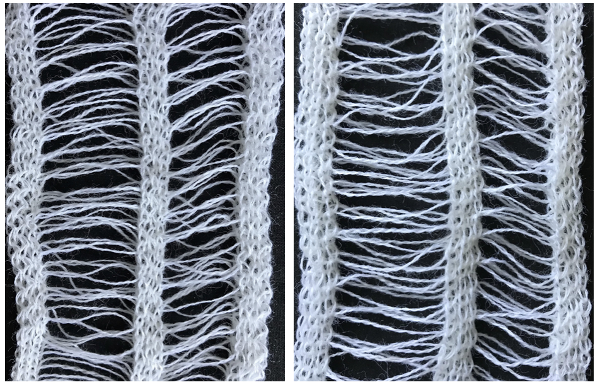

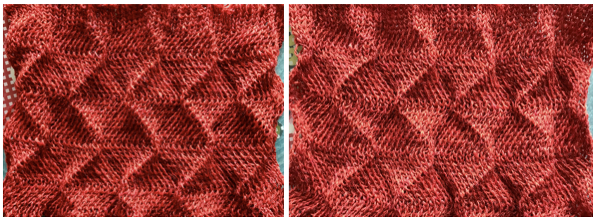

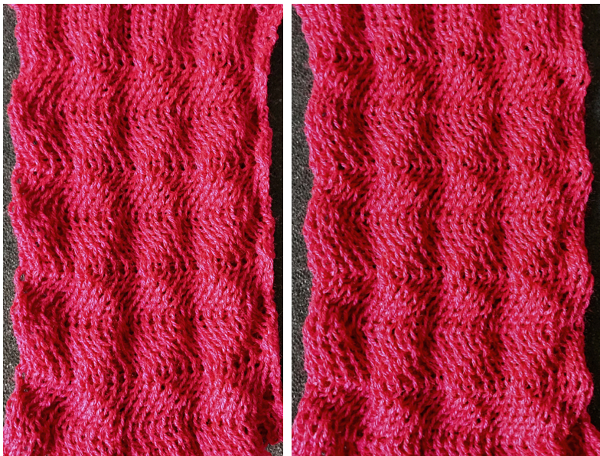

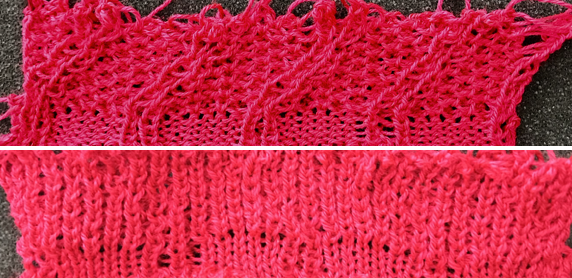

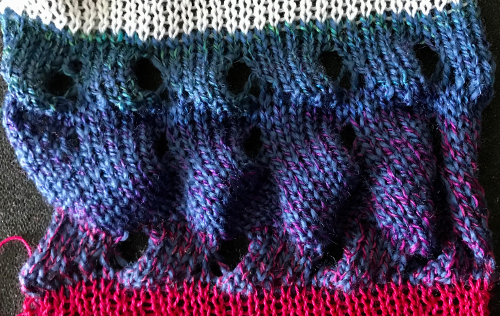

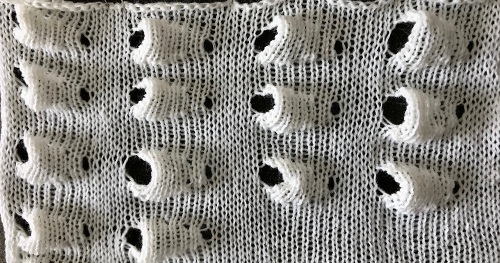

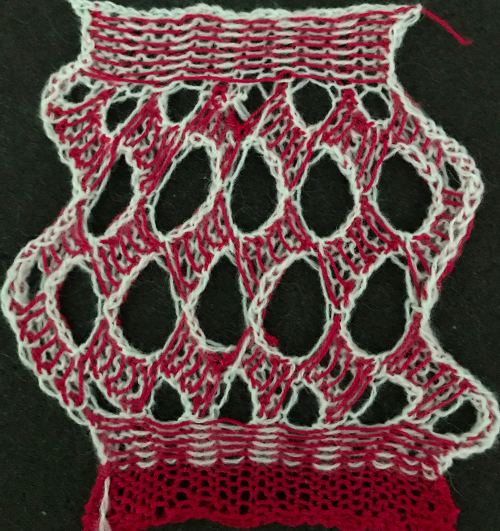

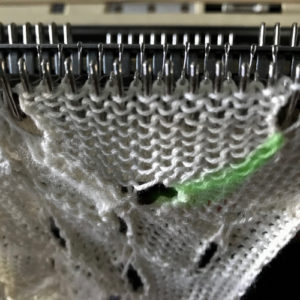

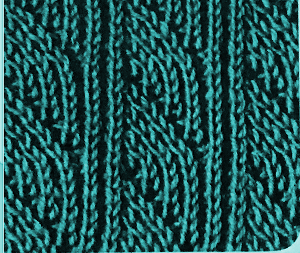

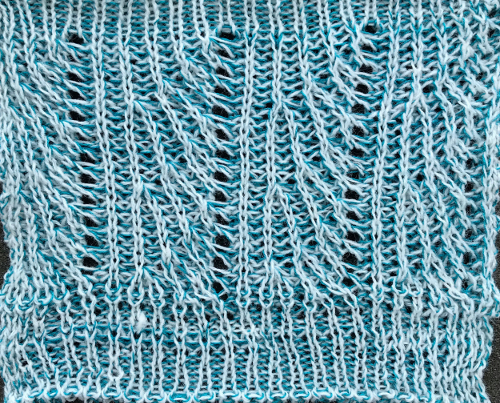

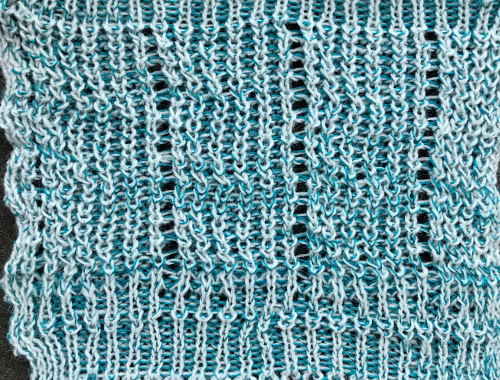

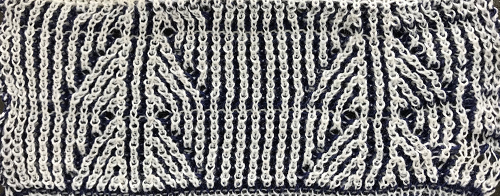

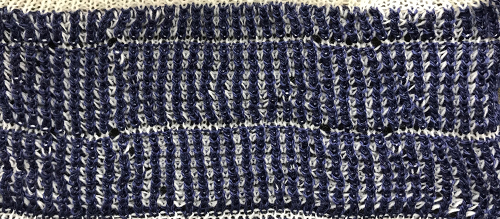

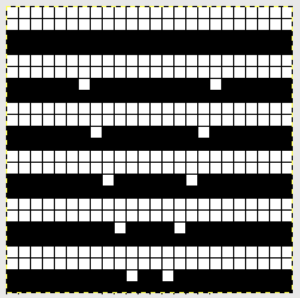

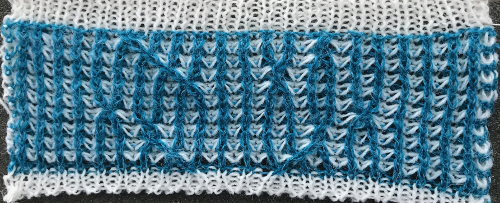

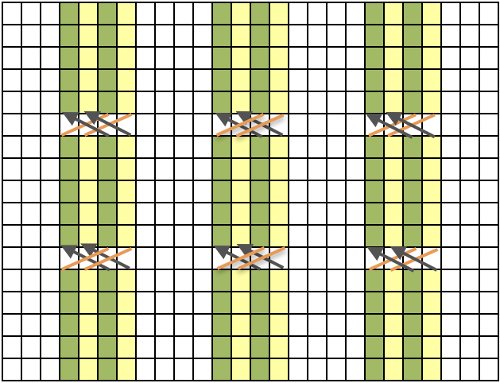

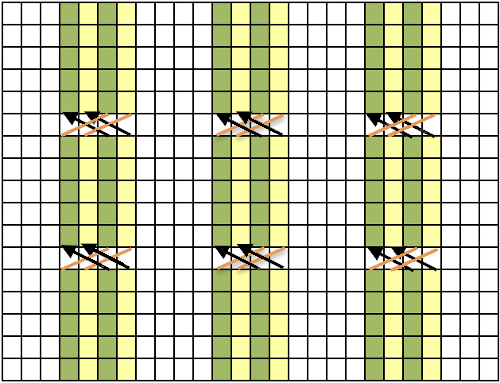

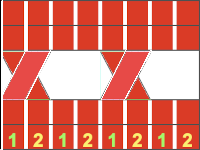

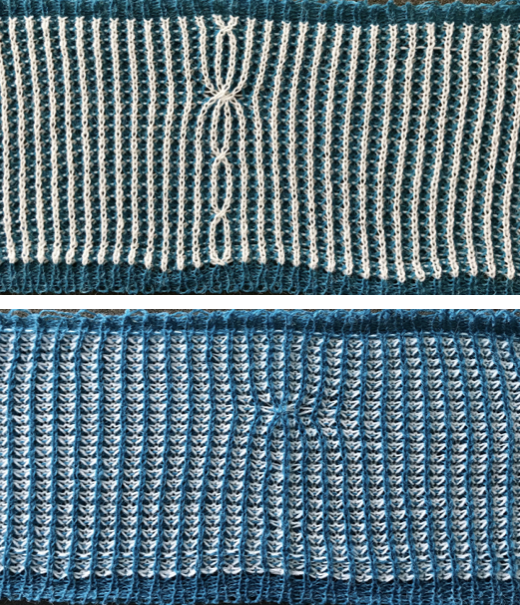

For a while, I was on an i-cord kick. I liked the look, but they were very time-consuming on production items, with lots of ends to weave in, and there was a balance to be sought between far too many to be practical and too few and skimpy to be attractive.  Here a ladder space created by needles out of work is left between vertical fair isle repeats, producing a fringe in 2 colors. The design was not planned, a standard punchcard was used for the purpose of the demo. A planned repeat would have more impact. End needle selection is on, which is usual in FI, not for most patterns with either tuck or slip stitch settings combined with needles out of work, is also true here so that a vertical line on each side of the needles out of work between repeats aids in sewing the strips together. Width is limited since the fabric will be gathered by seaming and become significantly narrower and likely turned sideways. Both sides are shown. Joining could be planned to occur only at the bottom of a piece if desired, stitching lines will be less visible if thread color matches that of the yarn

Here a ladder space created by needles out of work is left between vertical fair isle repeats, producing a fringe in 2 colors. The design was not planned, a standard punchcard was used for the purpose of the demo. A planned repeat would have more impact. End needle selection is on, which is usual in FI, not for most patterns with either tuck or slip stitch settings combined with needles out of work, is also true here so that a vertical line on each side of the needles out of work between repeats aids in sewing the strips together. Width is limited since the fabric will be gathered by seaming and become significantly narrower and likely turned sideways. Both sides are shown. Joining could be planned to occur only at the bottom of a piece if desired, stitching lines will be less visible if thread color matches that of the yarn

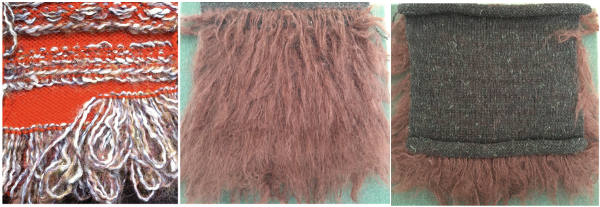

A needle in work away from the edge produces a side “fringe” followed here by felting partially, cutting the single edge stitch, and finishing the felting process

A needle in work away from the edge produces a side “fringe” followed here by felting partially, cutting the single edge stitch, and finishing the felting process

Adding thicker or multiple strands of yarns in long loops on edges, isolated areas, or all over

Adding thicker or multiple strands of yarns in long loops on edges, isolated areas, or all over  Let us not forget knit weaving with several strands of yarn, adding strips of the result as one knits, or simply hooking on strips of fake fur or thrums (the bits of yarn that litter the floor after you cut your weaving off the loom) at chosen intervals

Let us not forget knit weaving with several strands of yarn, adding strips of the result as one knits, or simply hooking on strips of fake fur or thrums (the bits of yarn that litter the floor after you cut your weaving off the loom) at chosen intervals

Finished edges on woven or lace trims, strips of fabric, and even roving along with self-made tassels may all be added at any point. Jolie tools, intended to aid in picking up dropped stitches can sometimes be helpful in picking up close to the woven edge (and pricking or piercing body parts on some days). The tool is available for both standard and bulky machines  Most often every other needle use is best. Here lace and pom trims are used, purchased fringes of all sorts could be applied the same way anywhere in the piece, joins to knit can be seen.

Most often every other needle use is best. Here lace and pom trims are used, purchased fringes of all sorts could be applied the same way anywhere in the piece, joins to knit can be seen.  A length of roving may be twisted in its center and applied as you knit. For a while mittens using it as a lining for warmth were popular. A video by Carole Wurst shows a method used in socks https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FWmH6XW_FU. Roving will felt together to varying degrees over time, as seen here in another of my ancient swatches. The “sparkle” is there as a result of using an angelica/wool blend.

A length of roving may be twisted in its center and applied as you knit. For a while mittens using it as a lining for warmth were popular. A video by Carole Wurst shows a method used in socks https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FWmH6XW_FU. Roving will felt together to varying degrees over time, as seen here in another of my ancient swatches. The “sparkle” is there as a result of using an angelica/wool blend.  the same twist in the center/ knit through method may be used with torn strips of silk or other thin fabrics, mine here are 1.5 cm. wide. Background yarn may knit fine at standard tension commonly used for it, testing will determine it and the spacing required to meet your goal

the same twist in the center/ knit through method may be used with torn strips of silk or other thin fabrics, mine here are 1.5 cm. wide. Background yarn may knit fine at standard tension commonly used for it, testing will determine it and the spacing required to meet your goal

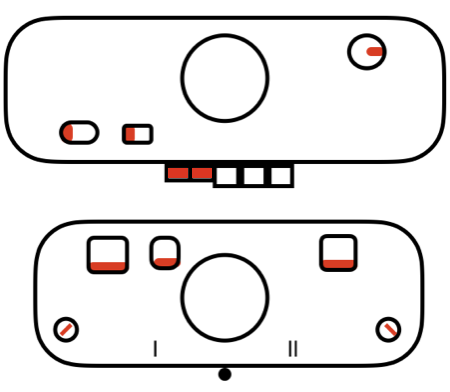

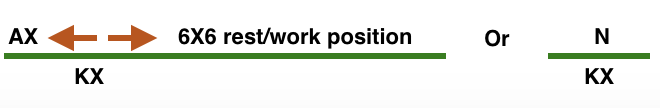

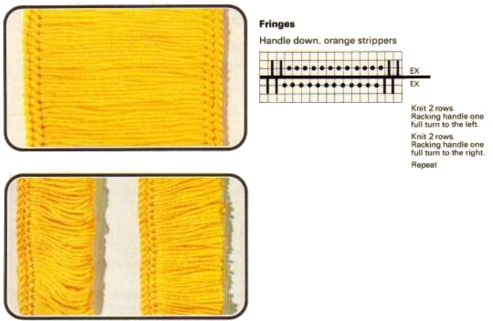

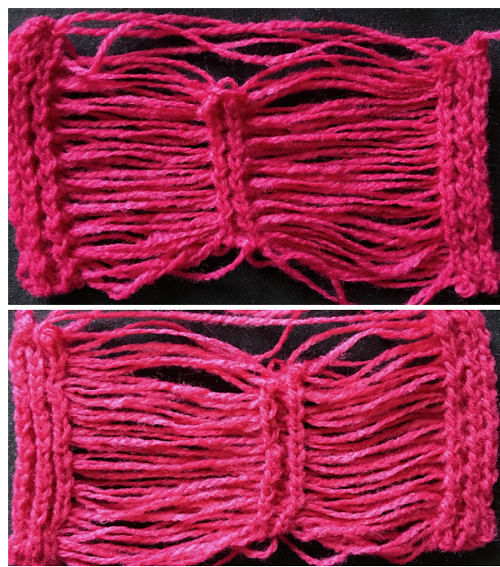

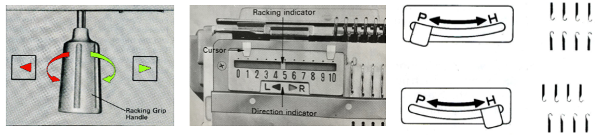

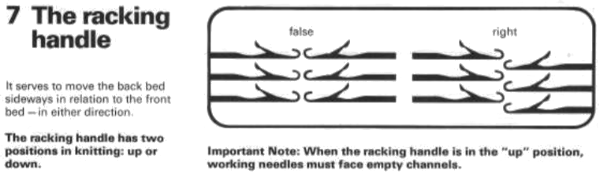

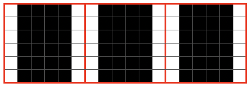

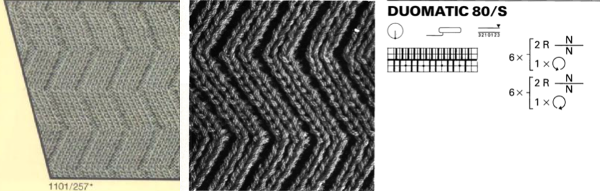

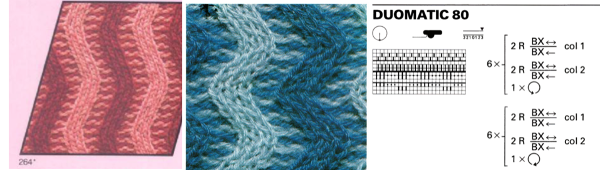

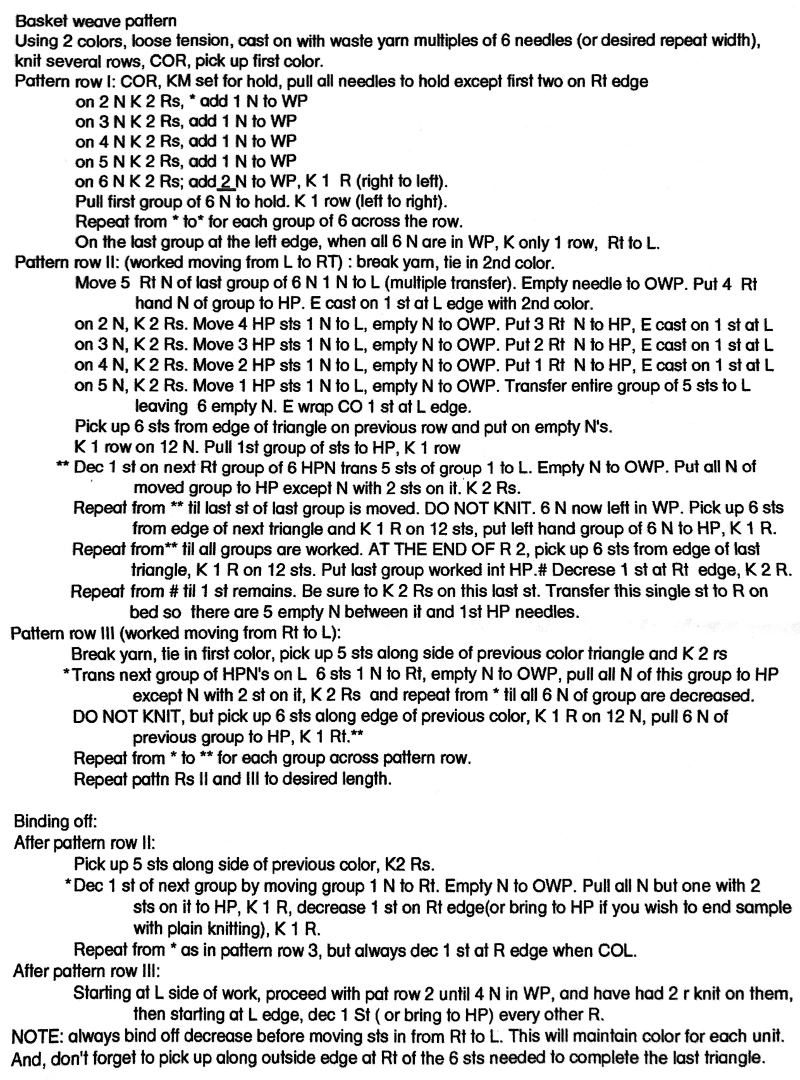

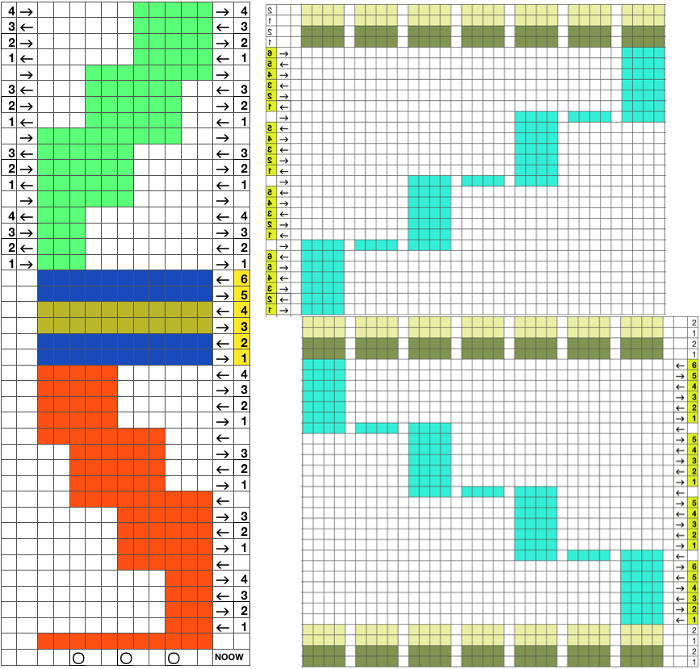

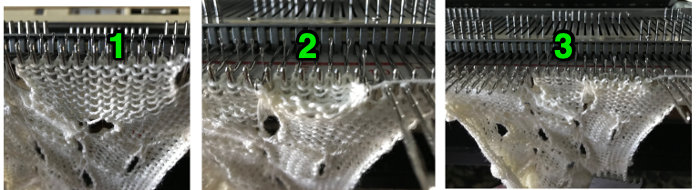

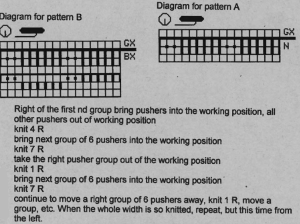

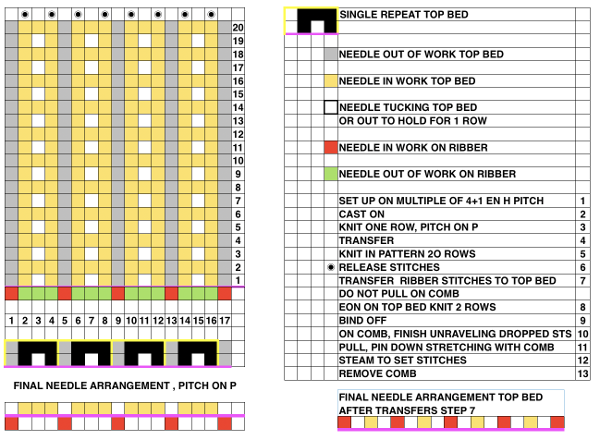

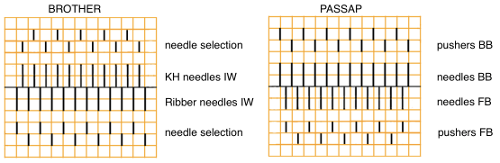

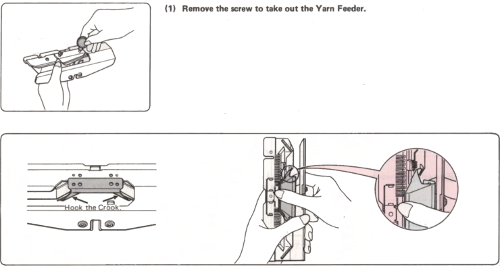

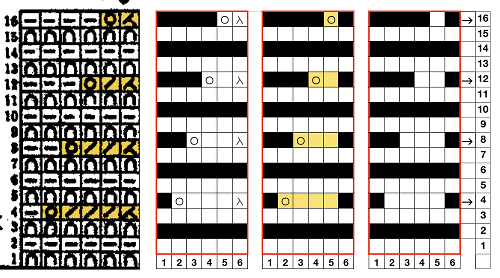

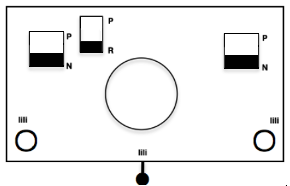

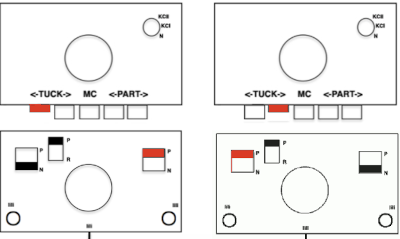

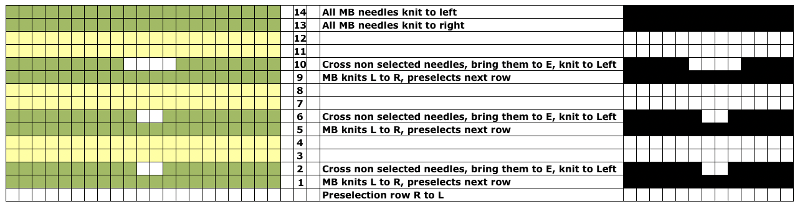

How-tos: to begin with, this is the “passap” version illustrated in the Duo Manual. One may choose wider knit bands between the floats that will be cut or folded over and doubled up

The thickness of the yarn chosen is of critical importance. When I first attempted to knit a version of it on my 930 I encountered problems. To start with, I kept dropping off the stitches on one side or the other. I checked the ribber alignment, proper placement of the cast on comb, switched ribbers, and carriages, and continued to have problems. After all that, the solution turned out to be simply adding another 4 stitches (2 on each bed) toward the center of the piece (I did not count). Here I used a 2/24 which obviously does not have enough body to use as an edging. The Brother equivalent for the Duo setting is half fisherman rib, where one carriage knits in one direction, tucks in the other on every needle for every 2 rows knit, while the other bed’s carriage does the same, but in opposite directions. I used 3 needles on each side rather than 2 as in the Duo repeat, starting with the first needle in work on the left on the ribber, the last needle in work on the right on the top bed. One may begin to knit on either side, but when manually setting the cam buttons lead with settings so that first stitch knits as it moves to the opposite side. Using waste yarn at the start of the piece will produce a better cast on edge for the trim. Operating from the right:

The thickness of the yarn chosen is of critical importance. When I first attempted to knit a version of it on my 930 I encountered problems. To start with, I kept dropping off the stitches on one side or the other. I checked the ribber alignment, proper placement of the cast on comb, switched ribbers, and carriages, and continued to have problems. After all that, the solution turned out to be simply adding another 4 stitches (2 on each bed) toward the center of the piece (I did not count). Here I used a 2/24 which obviously does not have enough body to use as an edging. The Brother equivalent for the Duo setting is half fisherman rib, where one carriage knits in one direction, tucks in the other on every needle for every 2 rows knit, while the other bed’s carriage does the same, but in opposite directions. I used 3 needles on each side rather than 2 as in the Duo repeat, starting with the first needle in work on the left on the ribber, the last needle in work on the right on the top bed. One may begin to knit on either side, but when manually setting the cam buttons lead with settings so that first stitch knits as it moves to the opposite side. Using waste yarn at the start of the piece will produce a better cast on edge for the trim. Operating from the right:

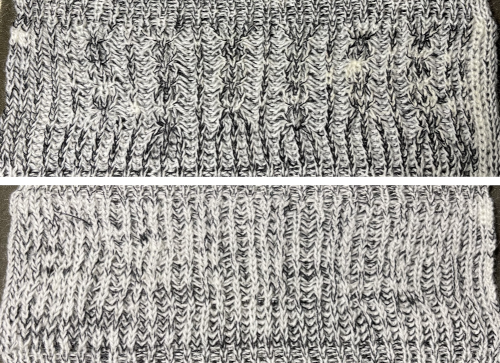

A 2/11.5 acrylic provided more of a tension adjustment challenge but made for a better fringe.

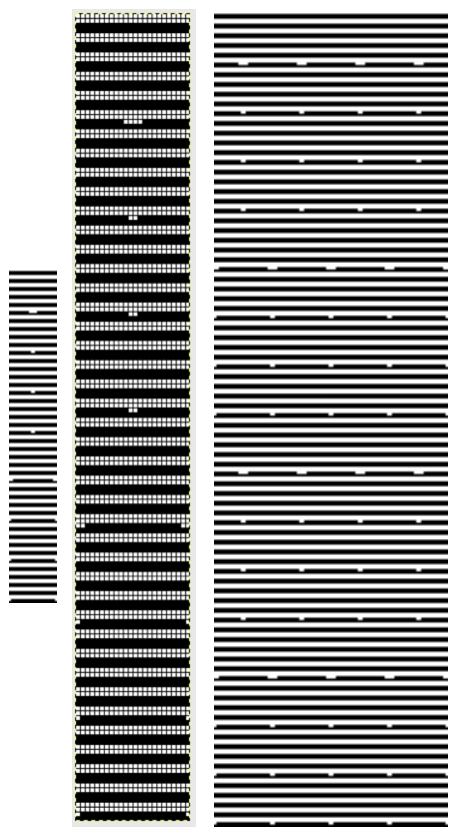

A 2/11.5 acrylic provided more of a tension adjustment challenge but made for a better fringe. The first and last 3 stitches on either side were transferred to the top bed and bound off, the center stitches were not, allowing them to be unraveled if desired ie in case the fringe is to be folded in half. Those extra center stitches also provide a guide for cutting either down their center (bottom of photo) or on either side of them (toward the top). I found the latter method to produce a cleaner cut line

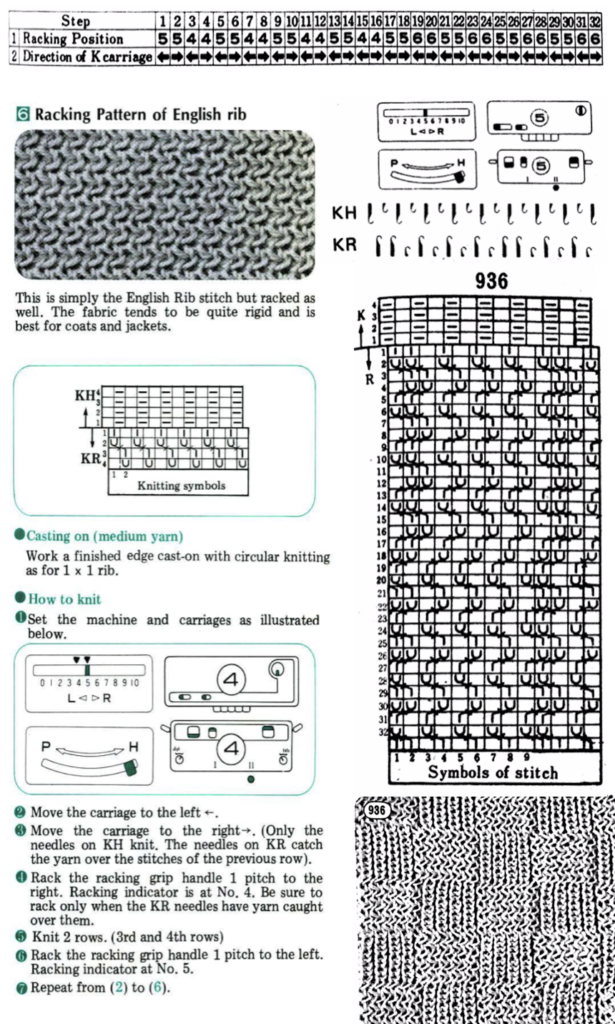

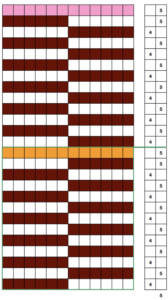

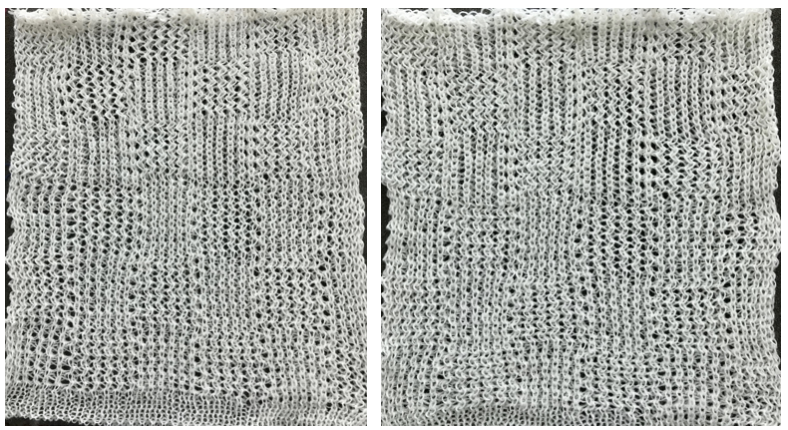

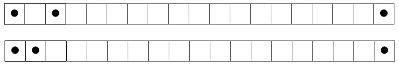

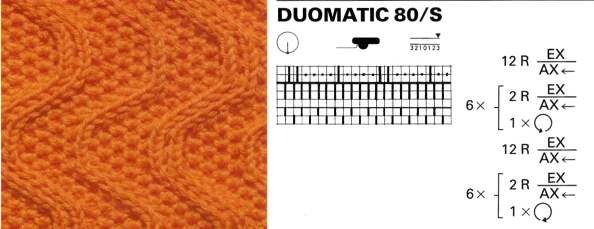

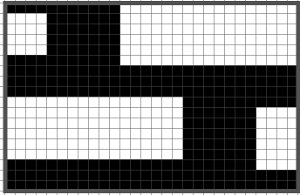

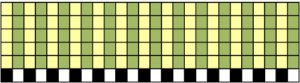

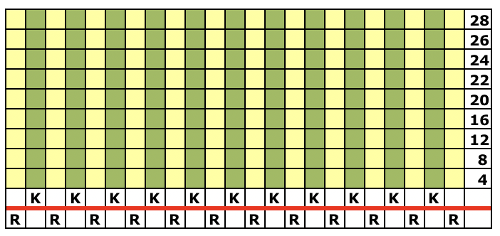

The first and last 3 stitches on either side were transferred to the top bed and bound off, the center stitches were not, allowing them to be unraveled if desired ie in case the fringe is to be folded in half. Those extra center stitches also provide a guide for cutting either down their center (bottom of photo) or on either side of them (toward the top). I found the latter method to produce a cleaner cut line Suggestions for going wider with racked half fisherman rib on Japanese machines: begin with needle arrangement below, out of work needles can be as many as needed, set up and cast on with preferred racking position ie on 5, knit several rows in waste yarn making any adjustments needed so stitches knit are formed properly, weigh appropriately.

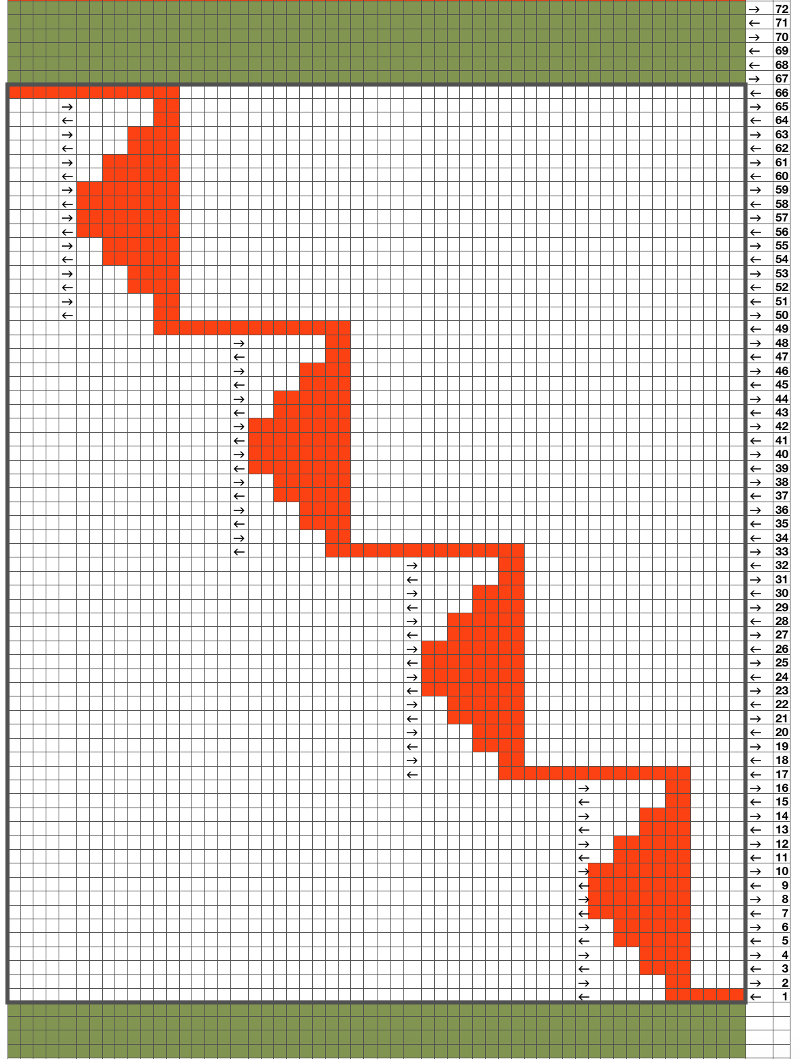

Suggestions for going wider with racked half fisherman rib on Japanese machines: begin with needle arrangement below, out of work needles can be as many as needed, set up and cast on with preferred racking position ie on 5, knit several rows in waste yarn making any adjustments needed so stitches knit are formed properly, weigh appropriately. ![]() Add needles on the main bed and remove one on the ribber

Add needles on the main bed and remove one on the ribber![]() Continue the test including in pattern, switch to a couple of rows of plain knitting and end with one knit row using ravel cord in a contrasting color. Cast on for fringe, knit 2 rows. Set for tuck rib, knit 2 rows, rack to position 4, knit 2 rows, rack to position 5, continue racking for the desired length, end with 2 knit rows and bind off or scrap off in case any additional length might be needed. When knitting lengths of trim, ending the piece on open stitches and waste knitting will give one the opportunity to either unravel or add more rows if needed.

Continue the test including in pattern, switch to a couple of rows of plain knitting and end with one knit row using ravel cord in a contrasting color. Cast on for fringe, knit 2 rows. Set for tuck rib, knit 2 rows, rack to position 4, knit 2 rows, rack to position 5, continue racking for the desired length, end with 2 knit rows and bind off or scrap off in case any additional length might be needed. When knitting lengths of trim, ending the piece on open stitches and waste knitting will give one the opportunity to either unravel or add more rows if needed.

Knitting fringes with a center band and cutting side edges will form variations on “feathers”. Pretend “hairpin lace ” produced on the knitting machine also uses related ideas.

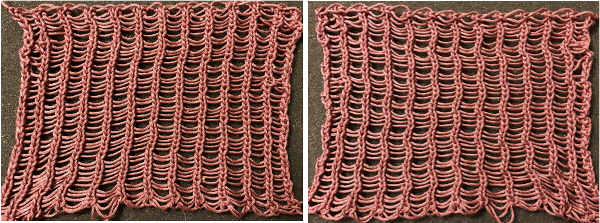

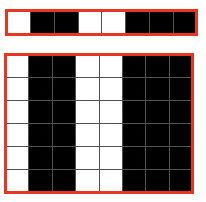

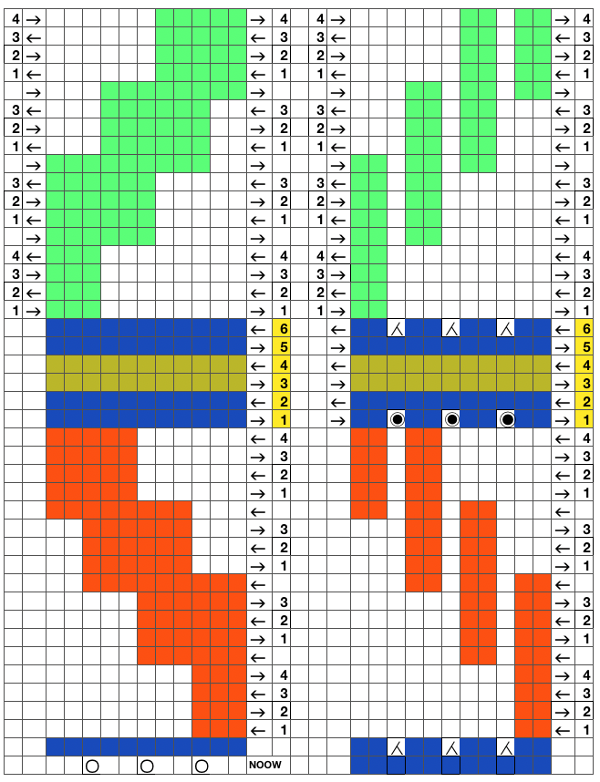

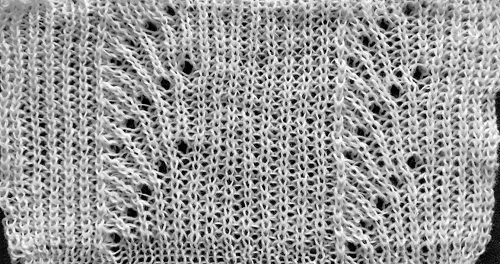

An aside tip: if knitting pieces with strips of stocking stitch between ladder spaces often the side edges of the vertical knit columns will not hold and become wider and distorted. Using a single stitch in from each side of the columns on the ribber as well and racking one to left, one to the right from the original position every one or 2 rows will stabilize them. This swatch was knit in a very slippery rayon/cotton blend over 20 years ago using single neighboring stitches on both beds the edge that holds the fringe together is to be very narrow (or even added as one continues to knit) and one wishes to work on the single bed there are several options. With 4-ply and a “matching color” 2 ply I began with the top needle arrangement, and then switched to the one below it, knitting on a 4.5 mm machine.

the edge that holds the fringe together is to be very narrow (or even added as one continues to knit) and one wishes to work on the single bed there are several options. With 4-ply and a “matching color” 2 ply I began with the top needle arrangement, and then switched to the one below it, knitting on a 4.5 mm machine.  A permanent cast-on needs to take place in the preferred method over needles in work knit 2 rows. The stitch on the second needle from the left is going to want to stretch and tends not to be stable. To reduce that happening, there are 2 options involving the second strand of yarn. Here using a 2 ply helps serve that purpose and keeps the fringed strands closer together. The slower method is to remove the second stitch from the left on a tool after every 2 rows knit, then bring the separate yarn strand behind the now empty needle first from the right, then in turn from the left, returning the removed stitch to the machine, knitting 2 rows. I found that too slow for my patience, switched to just laying the second strand over needles before knitting each pair of rows, and decided to eliminate the out of work needle on the left side, moving the second stitch in work to its left.

A permanent cast-on needs to take place in the preferred method over needles in work knit 2 rows. The stitch on the second needle from the left is going to want to stretch and tends not to be stable. To reduce that happening, there are 2 options involving the second strand of yarn. Here using a 2 ply helps serve that purpose and keeps the fringed strands closer together. The slower method is to remove the second stitch from the left on a tool after every 2 rows knit, then bring the separate yarn strand behind the now empty needle first from the right, then in turn from the left, returning the removed stitch to the machine, knitting 2 rows. I found that too slow for my patience, switched to just laying the second strand over needles before knitting each pair of rows, and decided to eliminate the out of work needle on the left side, moving the second stitch in work to its left.  The single stitch on the far right of the chart need not be bound off. There will be 2 options after the work is off the machine. One is to unravel the single stitch column on the far right if loops are the goal, or cut it off, leaving a fairly good trimmed edge here, and what, in this yarn, appeared to me to be an acceptable edging. The 2 edge stitches on the left in my swatch did roll, making a very tight edge. Adjusting the tension used to change that effect would be another choice. Yarn use and personal taste contribute to a range of “successful” results when using any of these techniques.

The single stitch on the far right of the chart need not be bound off. There will be 2 options after the work is off the machine. One is to unravel the single stitch column on the far right if loops are the goal, or cut it off, leaving a fairly good trimmed edge here, and what, in this yarn, appeared to me to be an acceptable edging. The 2 edge stitches on the left in my swatch did roll, making a very tight edge. Adjusting the tension used to change that effect would be another choice. Yarn use and personal taste contribute to a range of “successful” results when using any of these techniques.

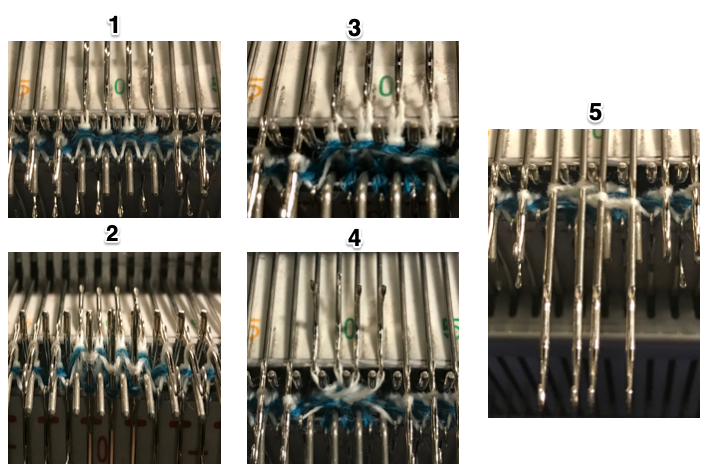

This version creates a true i-cord edging on one side, and produces a double fringe. Begin cast on with 5 stitches on one side, 1 on the opposite side to accommodate the desired width. As I knit my sample, I added a second stitch on that same side to make for an easier, more stable cutting line. Any changes in tension will affect the width and rigidity of the i-cord, and more markedly any stitches on the opposite side, and the length of the cut loops. As when knitting any slip stitch cords, the tension needs to be tightened by at least 2 numbers from that used in knitting the same yarn in stocking stitch. The carriage is set to slip in one direction, knit in the other, producing a float the width of the knit. Cast on. Beginning with COR knit one row to left, set the carriage to knit in one direction only (I happened to use the right part button, either can work). The process that draws the left side vertical column together into a cord : * transfer the fourth stitch from the left onto the fifth, move both stitches back onto the just emptied fourth needle, leave the fifth needle in work, “knit” 2 rows*. Technically, the 2 passes of the knit carriage to and from the left will produce only one knit row. I used the 2/11.5 acrylic, on the skimpy side. Thin yarns may be plied for the best effect. Here that second stitch has been added on the right, a few rows have been plain-knit.

This version creates a true i-cord edging on one side, and produces a double fringe. Begin cast on with 5 stitches on one side, 1 on the opposite side to accommodate the desired width. As I knit my sample, I added a second stitch on that same side to make for an easier, more stable cutting line. Any changes in tension will affect the width and rigidity of the i-cord, and more markedly any stitches on the opposite side, and the length of the cut loops. As when knitting any slip stitch cords, the tension needs to be tightened by at least 2 numbers from that used in knitting the same yarn in stocking stitch. The carriage is set to slip in one direction, knit in the other, producing a float the width of the knit. Cast on. Beginning with COR knit one row to left, set the carriage to knit in one direction only (I happened to use the right part button, either can work). The process that draws the left side vertical column together into a cord : * transfer the fourth stitch from the left onto the fifth, move both stitches back onto the just emptied fourth needle, leave the fifth needle in work, “knit” 2 rows*. Technically, the 2 passes of the knit carriage to and from the left will produce only one knit row. I used the 2/11.5 acrylic, on the skimpy side. Thin yarns may be plied for the best effect. Here that second stitch has been added on the right, a few rows have been plain-knit.  This shows the length of the slipped row, and that a loop is formed on the return to the other side on the empty but in work needle # 5.

This shows the length of the slipped row, and that a loop is formed on the return to the other side on the empty but in work needle # 5.  The transfers from needle 4 to 5 and back have been made, leaving the empty needle 5 in work.

The transfers from needle 4 to 5 and back have been made, leaving the empty needle 5 in work.  At the top of the piece, I transferred and doubled up the stitches on left, bound them off, and the yarn end(s) can be woven back into the cord.

At the top of the piece, I transferred and doubled up the stitches on left, bound them off, and the yarn end(s) can be woven back into the cord.  The side with the transfers is the “public” one, the finished fringe is usually hand sewn on, but it may also be used to cast on or be applied to several places in the knit both close together or at various intervals. Tension changes may be observed viewing from left to right, as well as the difference in length of loops as opposed to after the cutaway edge. The third stitch in work on the right may make for a more stable cutting line if looser tensions are preferred. Because the sinker plate used on the single bed has brushes and wheels in use, the width of the fringe can be considerable, without having to be concerned about stabilizing the center as it is when working on the double bed.

The side with the transfers is the “public” one, the finished fringe is usually hand sewn on, but it may also be used to cast on or be applied to several places in the knit both close together or at various intervals. Tension changes may be observed viewing from left to right, as well as the difference in length of loops as opposed to after the cutaway edge. The third stitch in work on the right may make for a more stable cutting line if looser tensions are preferred. Because the sinker plate used on the single bed has brushes and wheels in use, the width of the fringe can be considerable, without having to be concerned about stabilizing the center as it is when working on the double bed.

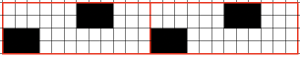

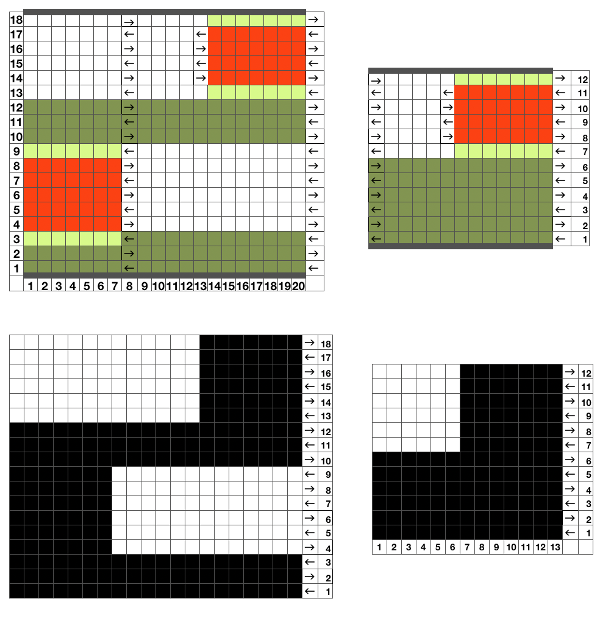

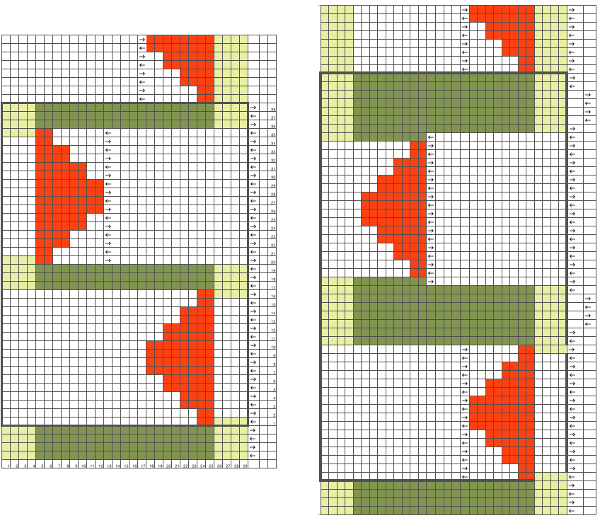

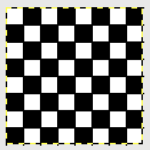

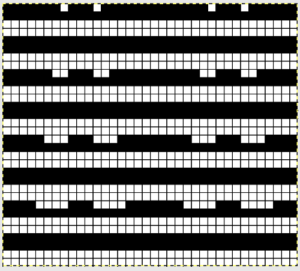

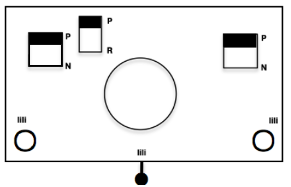

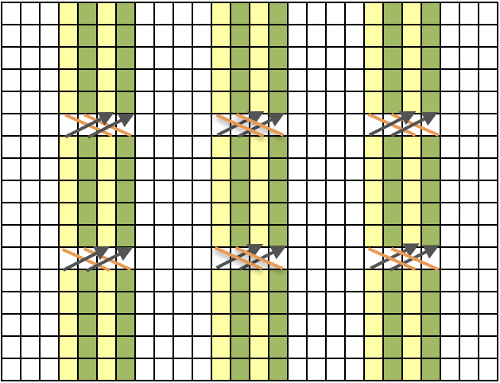

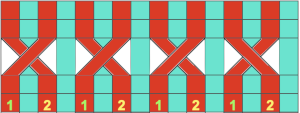

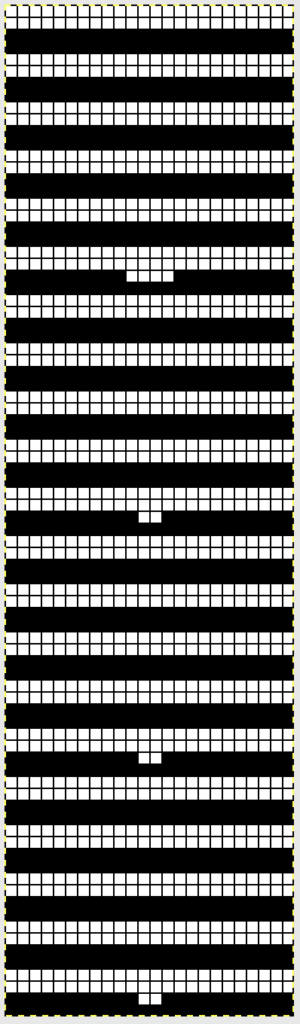

Introducing patterning single bed: knit weaving is perhaps the best way to control the number of plies, color mixing, designs in vertical bands, and knitting 2 fringe lengths at the same time. The 1/1 brother card is the most basic, but small repeats can be isolated for more interest or syncing with designs in garment pieces. To start: cast on and knit at least 2 rows on the chosen needle arrangement. Hang claw weights (or smaller) on each block of stitches. Combining strands for weaving adds fullness to the fringe. When any fringe is removed from the machine it should be stretched lengthwise and steamed to set the stitches (which I did not do in any of my swatches). As with other samples, the odd small number of stitches in the center or on the side are cut off to release the fringe. A sample arrangement: odd number of needles on either side and center, even number of needles out of work in-between. ![]() Visualizing the punchcard or electronic needle selection on the same number of needles in work as above helps. Here the first and last needle on each side knits at the start. End needle selection is off; if it is not the outside automatic needle selection will give that edge a different look. Using both settings will help determine if one is more preferred than the other.

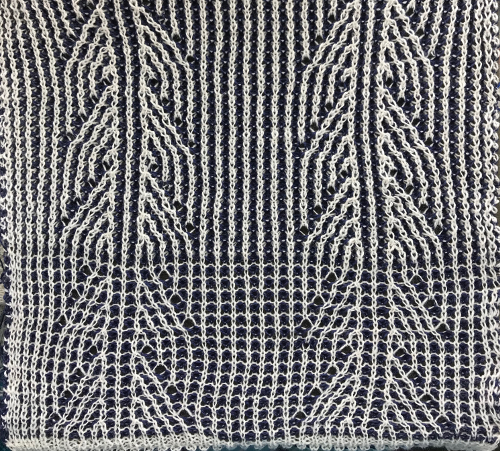

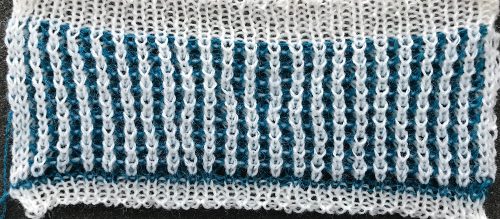

Visualizing the punchcard or electronic needle selection on the same number of needles in work as above helps. Here the first and last needle on each side knits at the start. End needle selection is off; if it is not the outside automatic needle selection will give that edge a different look. Using both settings will help determine if one is more preferred than the other. ![]() A closer look at both sides of my ancient swatch knit in 2/8 wool

A closer look at both sides of my ancient swatch knit in 2/8 wool

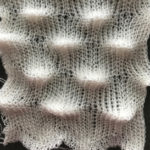

Long loops are best in a thicker yarn, here they are shown in an every other needle arrangement using mohair on 2/8 wool ground

Long loops are best in a thicker yarn, here they are shown in an every other needle arrangement using mohair on 2/8 wool ground related post reviews some of the methods for creating the loops, there is at least one other. Published directions have taken it for granted that thinner yarn is in use: if working on a machine with a ribber use the gate pegs on the ribber as your gauge. Wind the yarn around the needle, then down to the sinker plate below it with ribber down one position, then around the same needle, down to the same gate peg, then up and around the next needle, continuing across. When the row of loops is completed, knit several rows, and lift the ribber up to release loops.

related post reviews some of the methods for creating the loops, there is at least one other. Published directions have taken it for granted that thinner yarn is in use: if working on a machine with a ribber use the gate pegs on the ribber as your gauge. Wind the yarn around the needle, then down to the sinker plate below it with ribber down one position, then around the same needle, down to the same gate peg, then up and around the next needle, continuing across. When the row of loops is completed, knit several rows, and lift the ribber up to release loops.

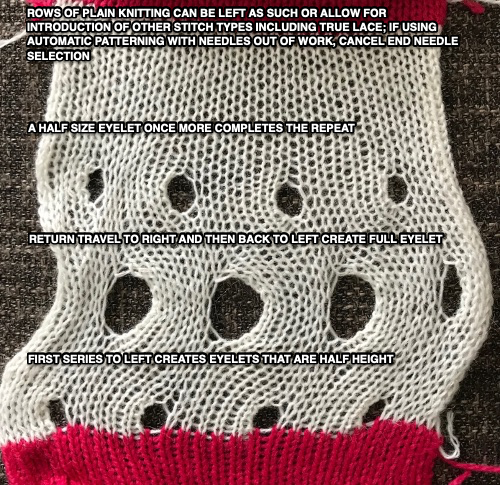

My test is with yarns of 2 thicknesses, one half the number of plies in the other. Cast on with background yarn, knit at least 2 rows. I wrapped the 4-ply on every needle on the main bed counterclockwise when moving from left to right (think e wrapping in either direction), clockwise when moving from right to left, bringing it down and around the corresponding gate peg. I found it easier to work with needles that were to be wrapped and moved forward from the B position.  The loops prior to being lifted off sinker plates

The loops prior to being lifted off sinker plates  The first ribber height drop produced short loops (2.5 cm)

The first ribber height drop produced short loops (2.5 cm) With ribber in the down most position (4.5 cm loops)

With ribber in the down most position (4.5 cm loops)

I found that just by knitting 3 more rows in this yarn I could lift the loops off the ribber gate pegs easily, dropping them between the beds and repeating the process. No need to raise the ribber back up. Whether these loops will bear being cut or be too slippery to stay in the ground will be determined by yarn choices.

I found that just by knitting 3 more rows in this yarn I could lift the loops off the ribber gate pegs easily, dropping them between the beds and repeating the process. No need to raise the ribber back up. Whether these loops will bear being cut or be too slippery to stay in the ground will be determined by yarn choices.

There are times when a fringe is desired on one or both sides of the piece. Simply leaving needles out of work and an additional one in use to determine the width of the fringe can have skimpy results and an unstable edge stitch on the knit body. This is my solution for solving both: I began by knitting a couple of rows in the background yarn, then added a strand of yellow, and eventually the third strand in light blue, e wrapping the extra strand(s) in the direction away from the carriage.

In this case, knitting ended opposite the fringe, only these stitches were bound off, not the single one on the far right

In this case, knitting ended opposite the fringe, only these stitches were bound off, not the single one on the far right  The single stitch column was trimmed off, leaving a fairly full, stable fringe.

The single stitch column was trimmed off, leaving a fairly full, stable fringe.

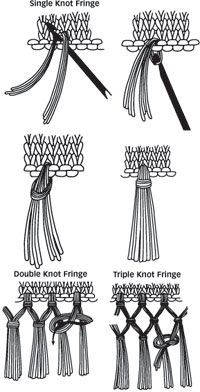

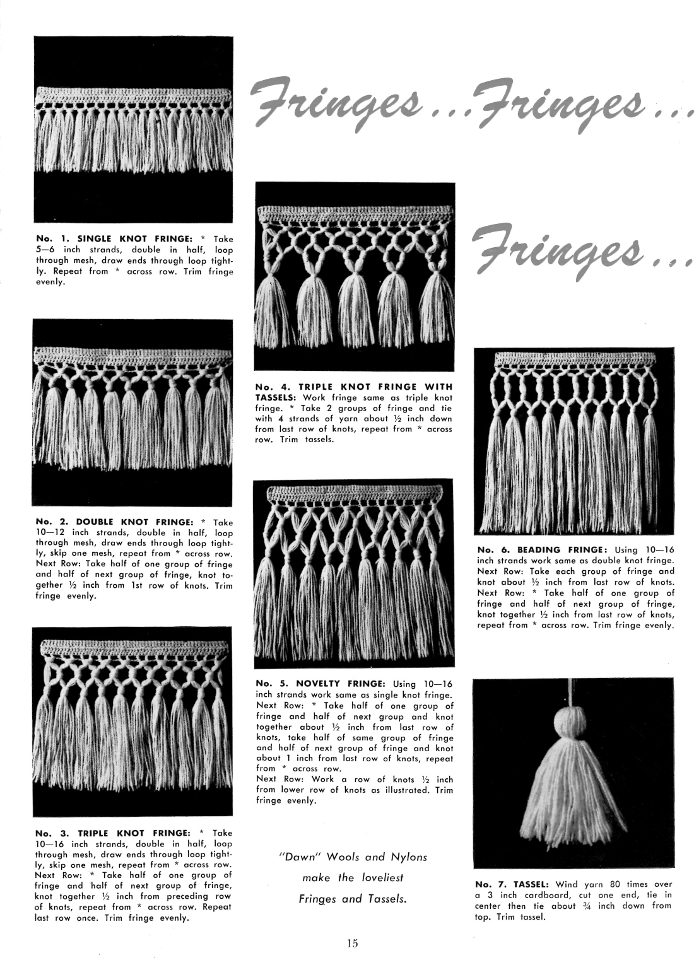

Cut lengths of yarn may be added to edge or in the body of the knit, eyelets could be used as markers or for an all-over fabric, guiding placement. This illustration is from Annie’s catalog

Cut lengths of yarn may be added to edge or in the body of the knit, eyelets could be used as markers or for an all-over fabric, guiding placement. This illustration is from Annie’s catalog  Fringes could also be crocheted or hand-knit, used to cast on the piece or be stitched in place upon its completion. I do not have the source for this, will credit it if I can find one

Fringes could also be crocheted or hand-knit, used to cast on the piece or be stitched in place upon its completion. I do not have the source for this, will credit it if I can find one

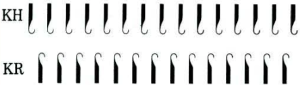

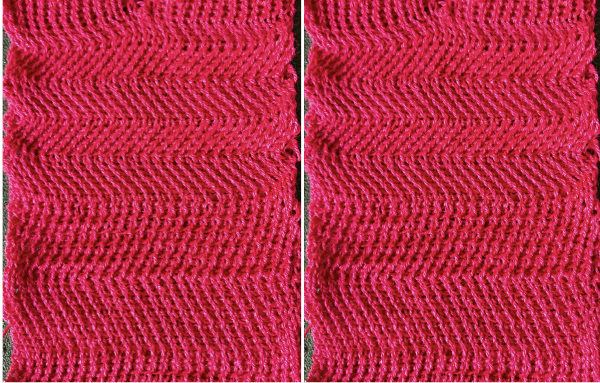

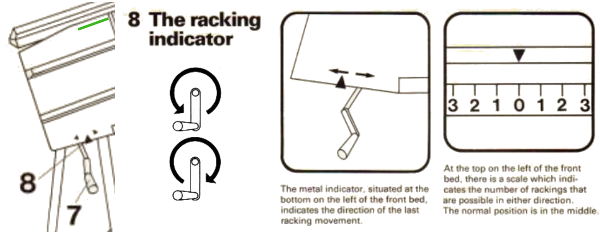

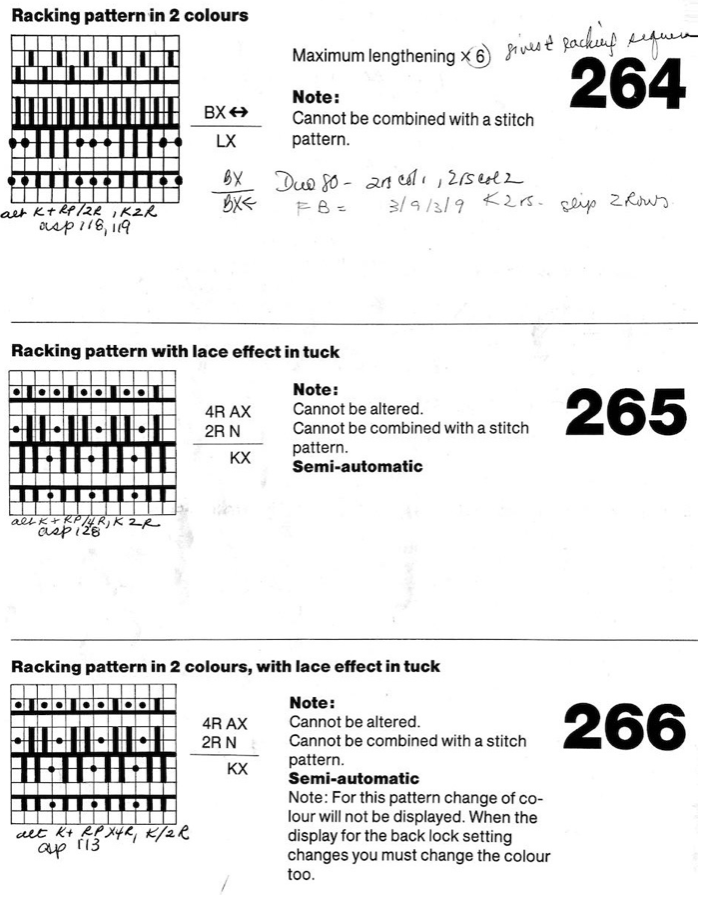

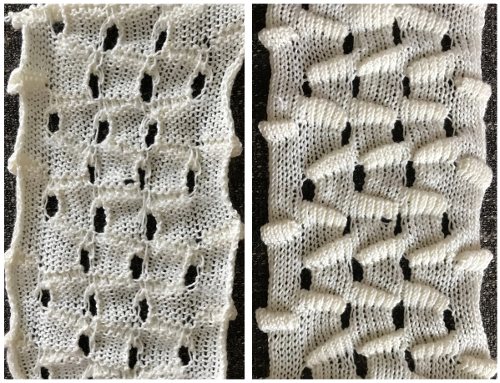

The only way to find out is to try it. The lesson already learned: use a yarn that is crisp or capable of retaining memory for maximum effect. Here the swatch is knit in a 3/14 cotton. To start with, racking was from position 0 to 6 and back. Racking every 2 rows at the bottom of the sample, every row at its top

The only way to find out is to try it. The lesson already learned: use a yarn that is crisp or capable of retaining memory for maximum effect. Here the swatch is knit in a 3/14 cotton. To start with, racking was from position 0 to 6 and back. Racking every 2 rows at the bottom of the sample, every row at its top Now adding needles out of work with the expectation of folds at approximate center of each fold

Now adding needles out of work with the expectation of folds at approximate center of each fold Racking started in center position 0, then swung to 3 left, to 3 right, ending on 0. I long ago got frustrated with the Passap numbering, marked the racking positions with a permanent marker from 0 on the right to 6 on the left. The knit result is definitely a rolling fabric, though a bit less so than the Brother sample which was able to move across more racking positions

Racking started in center position 0, then swung to 3 left, to 3 right, ending on 0. I long ago got frustrated with the Passap numbering, marked the racking positions with a permanent marker from 0 on the right to 6 on the left. The knit result is definitely a rolling fabric, though a bit less so than the Brother sample which was able to move across more racking positions

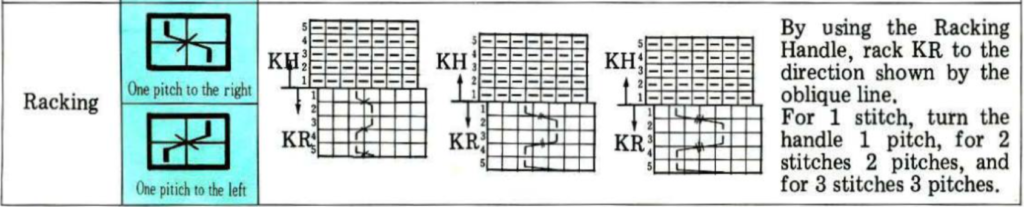

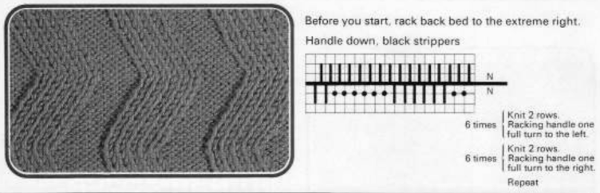

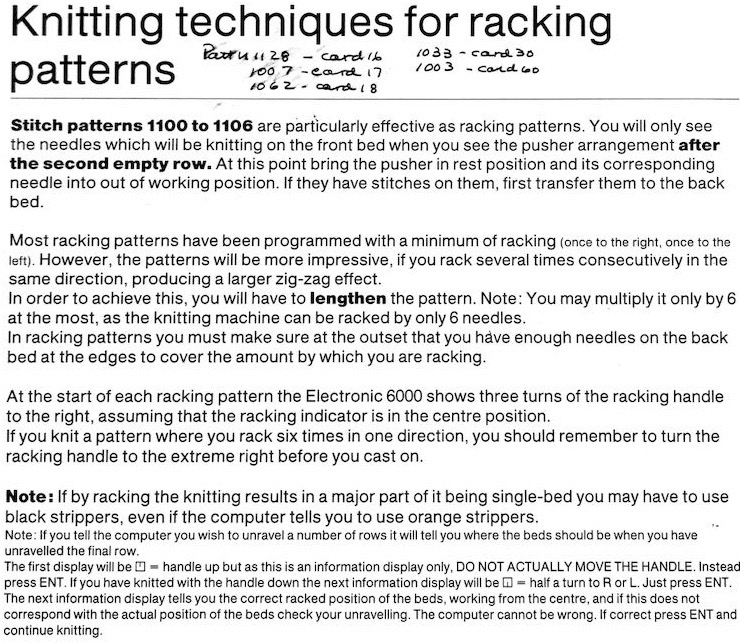

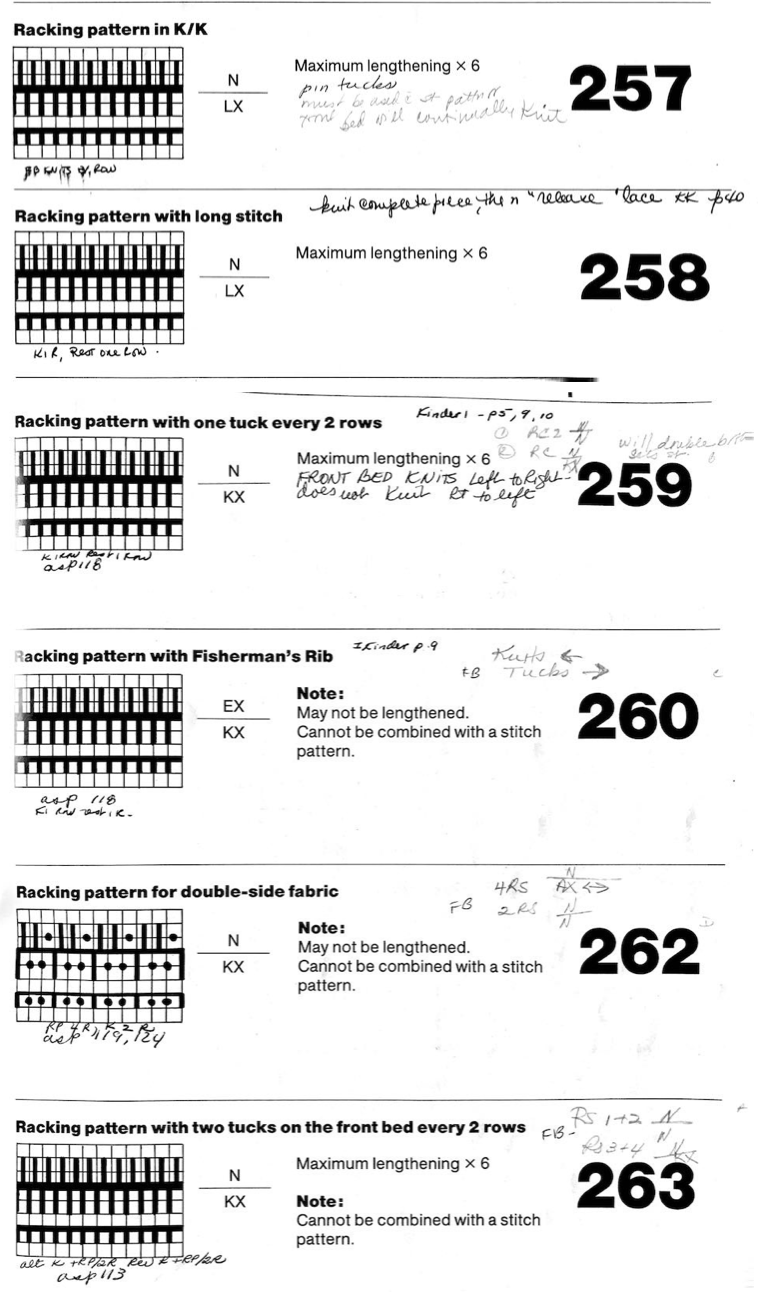

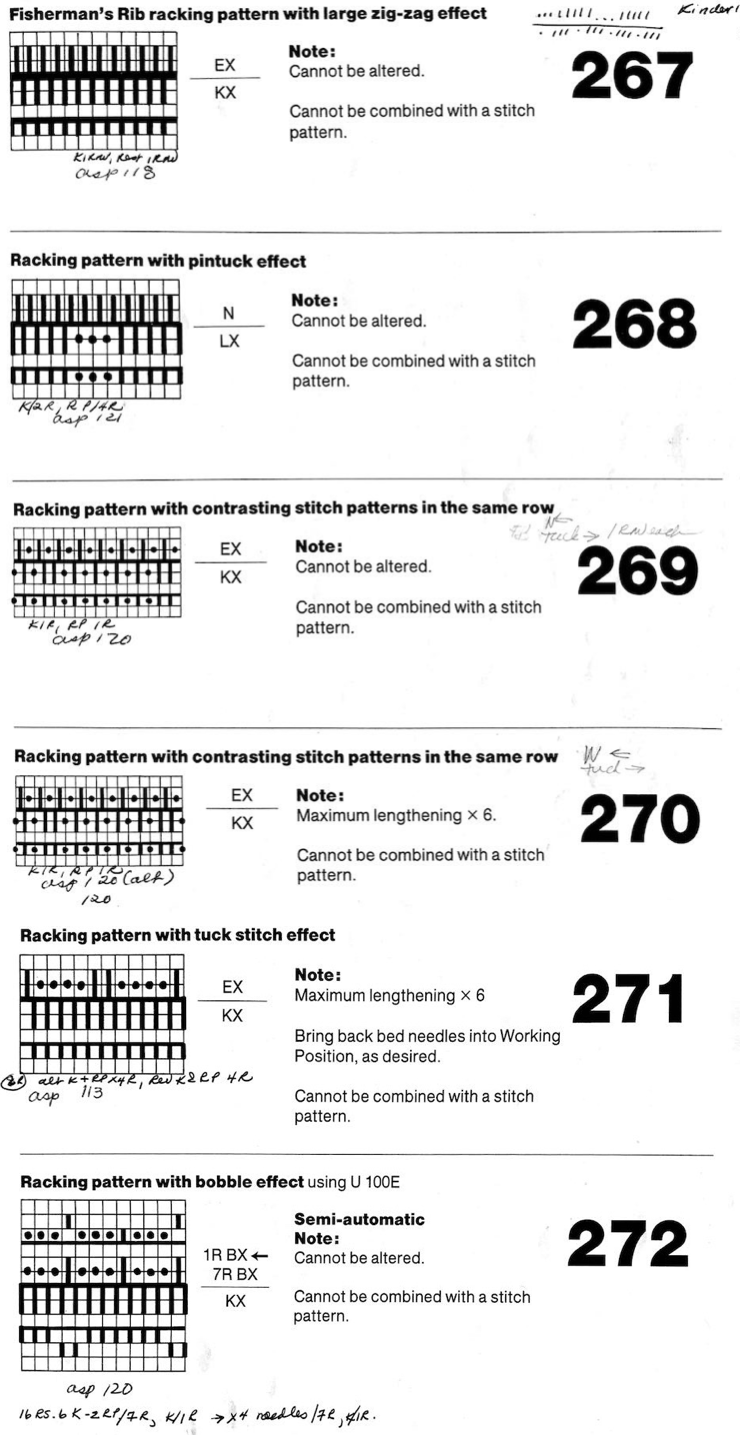

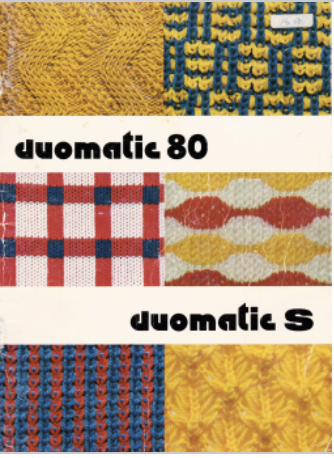

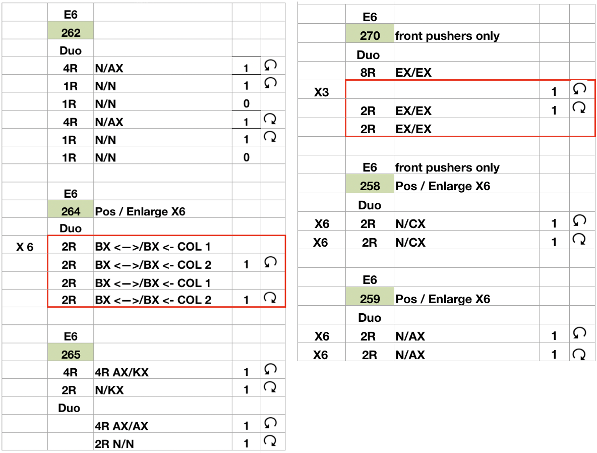

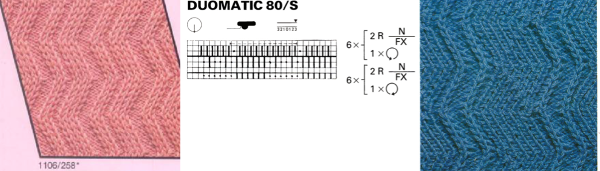

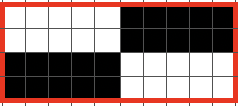

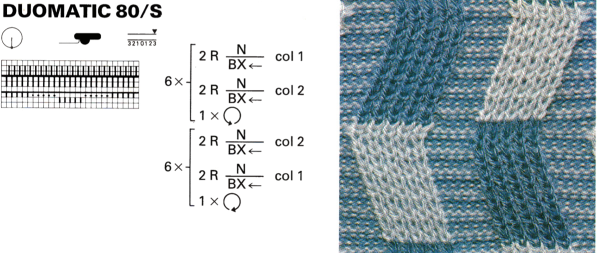

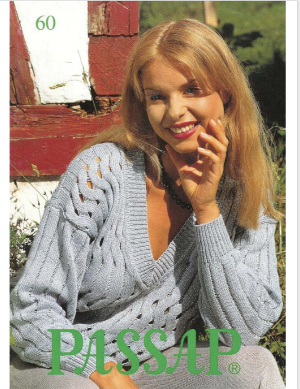

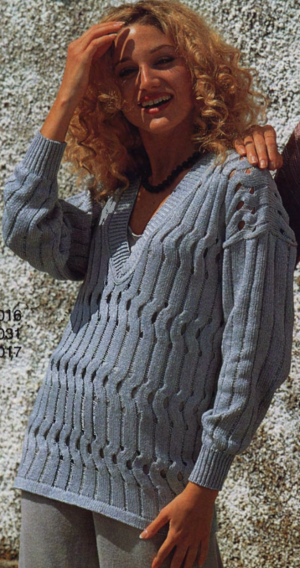

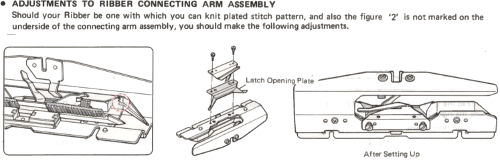

Passap E6 manual shows racking patterns possible with console built-in designs on pp. 118, 119, 120, 121, techniques used in racking patterns number 257-272. The console gives prompts for the direction in racking sequences. Self-programmed designs would need a separate knitting technique entered into the console as an additional “design”. This can be done with a card reader combined with a pattern download from a computer. Programs that automated the function to any degree are no longer on the market. Typically, in published patterns for either brand, if the starting point for the racking sequence is important, it will be given along with the frequency of movements such as in this design from the Duo 80 book

Passap E6 manual shows racking patterns possible with console built-in designs on pp. 118, 119, 120, 121, techniques used in racking patterns number 257-272. The console gives prompts for the direction in racking sequences. Self-programmed designs would need a separate knitting technique entered into the console as an additional “design”. This can be done with a card reader combined with a pattern download from a computer. Programs that automated the function to any degree are no longer on the market. Typically, in published patterns for either brand, if the starting point for the racking sequence is important, it will be given along with the frequency of movements such as in this design from the Duo 80 book

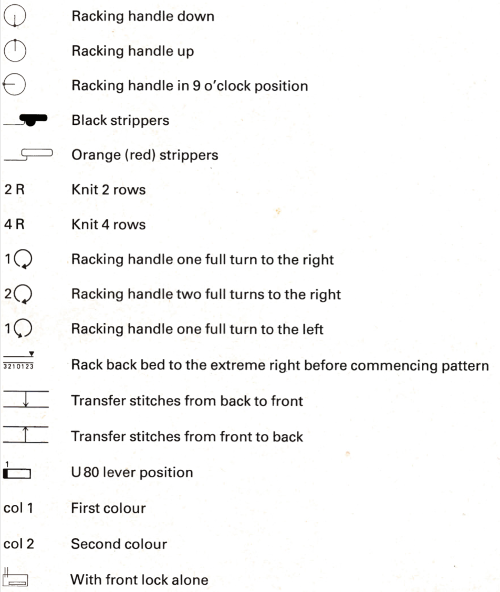

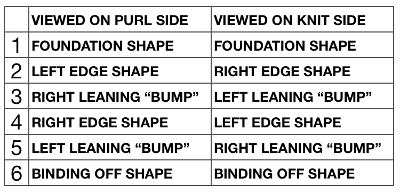

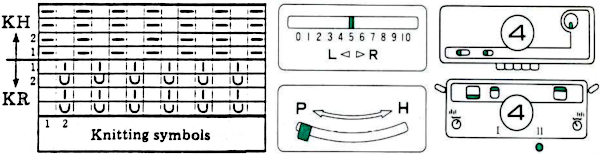

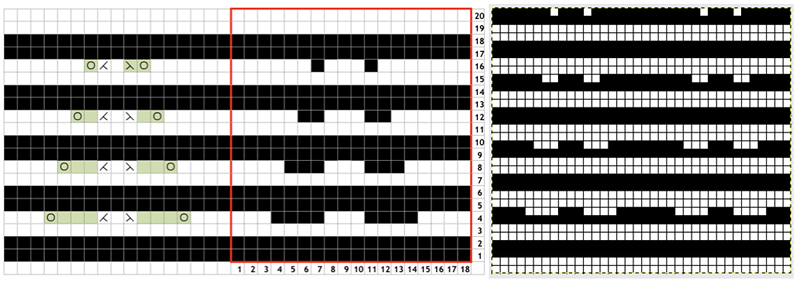

Some Duo symbols and their meaning

Some Duo symbols and their meaning

My sample was knit in a tightly twisted cotton, and when off the machine had an interesting and unexpected fold 3Dquality

My sample was knit in a tightly twisted cotton, and when off the machine had an interesting and unexpected fold 3Dquality

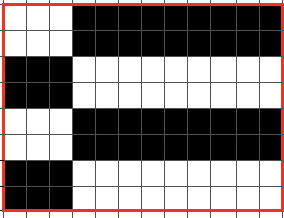

The setup is essentially the same, with white squares representing needles and pushers that need to be out of work. Tech 258 uses LX (slip) on the front bed, back bed si set to N. The duomatic pattern has a different OOW needle arrangement, the front lock is also set to tuck = FX (E6=KX), adding another layer of texture and complexity. Needles are also out of work on the back bed.

The setup is essentially the same, with white squares representing needles and pushers that need to be out of work. Tech 258 uses LX (slip) on the front bed, back bed si set to N. The duomatic pattern has a different OOW needle arrangement, the front lock is also set to tuck = FX (E6=KX), adding another layer of texture and complexity. Needles are also out of work on the back bed.

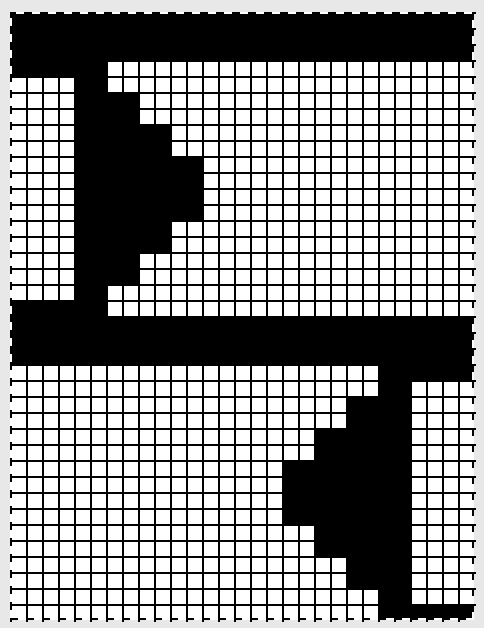

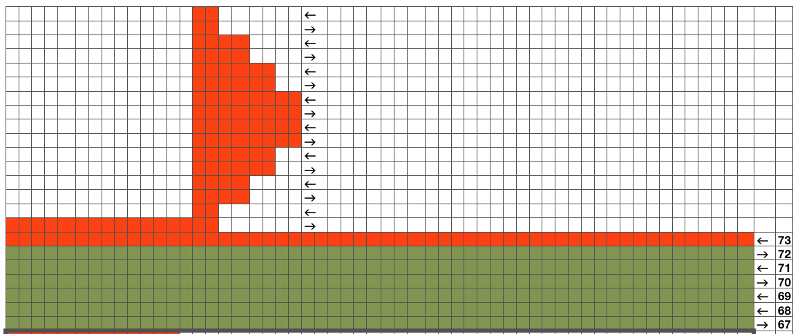

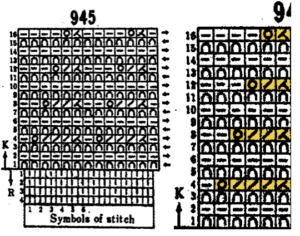

What is knitting in terms of black and white squares if one continues:

What is knitting in terms of black and white squares if one continues:

this repeat is what is required to match the technique diagram

this repeat is what is required to match the technique diagram

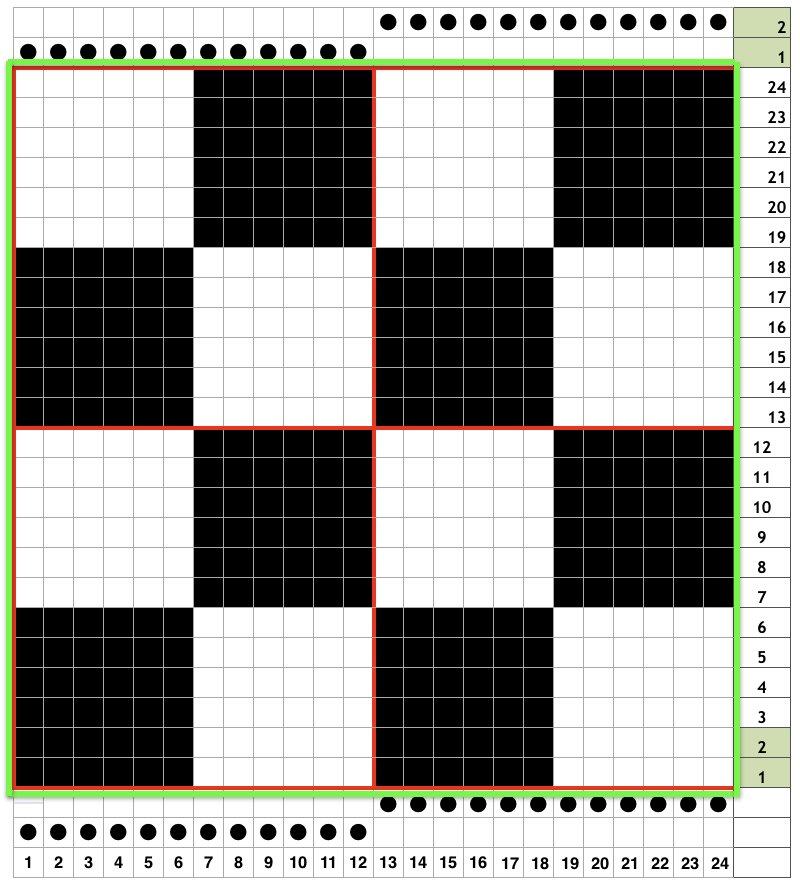

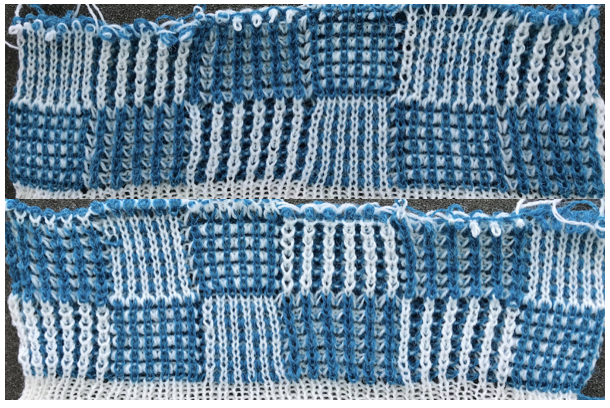

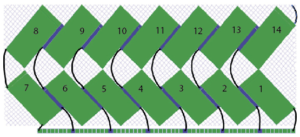

Below the pattern alternates blocks of 5 black squares, 5 white, color changing every 2 rows and reversing racking direction after every 24 rows. The full repeat is 48 rows. If rows knit in the zig-zag are counted, they amount to 12 because each color slips it is not knitting for 2 rows. Note that to achieve the color reversal at the halfway point of the repeat the same color (2) knits for 4 rows, at the top of the repeat color 1 does the same.

Below the pattern alternates blocks of 5 black squares, 5 white, color changing every 2 rows and reversing racking direction after every 24 rows. The full repeat is 48 rows. If rows knit in the zig-zag are counted, they amount to 12 because each color slips it is not knitting for 2 rows. Note that to achieve the color reversal at the halfway point of the repeat the same color (2) knits for 4 rows, at the top of the repeat color 1 does the same.

Back to acrylic yarn, light color for more visibility creative yarn snag on the left midway, full swing movement is shown, each is 48 rows in height. As always it helps to check whether stitches are obliging by staying on the needle bed. The top half of the swatch is shown.

Back to acrylic yarn, light color for more visibility creative yarn snag on the left midway, full swing movement is shown, each is 48 rows in height. As always it helps to check whether stitches are obliging by staying on the needle bed. The top half of the swatch is shown. In turn, I programmed # 1000 X 6 in height but pusher selection was all up for one row, one down. I left it alone, and lastly, worked with pusher selection on the back bed, BX <–. Patterning advances a fixed repeat every row or every other, determined by original hand-selected up for selection and down above rail for out of selection. The front lock is left on N (disregard front for setting it to LX) there is a whole other world of possibilities, while the console racking sequences can be used from built-in techniques.

In turn, I programmed # 1000 X 6 in height but pusher selection was all up for one row, one down. I left it alone, and lastly, worked with pusher selection on the back bed, BX <–. Patterning advances a fixed repeat every row or every other, determined by original hand-selected up for selection and down above rail for out of selection. The front lock is left on N (disregard front for setting it to LX) there is a whole other world of possibilities, while the console racking sequences can be used from built-in techniques.  Any ribber needle selection on Brother other than the use of lili buttons would have to be done manually.

Any ribber needle selection on Brother other than the use of lili buttons would have to be done manually. a rearview with ends woven in

a rearview with ends woven in

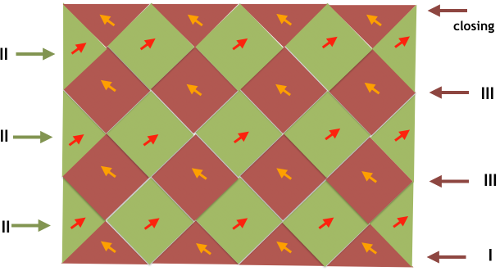

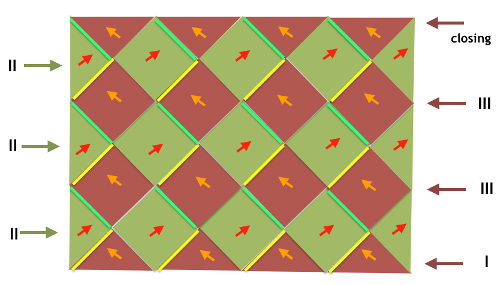

When the end of the first row that row is reached, as contrast color is added, stitches need to be cast on on the far left in order to keep the work on the bed a constant number of stitches. The usual method suggested is e wrapping, this is picking up from the row below. I found either method produced looser, longer stitches on the far edge

When the end of the first row that row is reached, as contrast color is added, stitches need to be cast on on the far left in order to keep the work on the bed a constant number of stitches. The usual method suggested is e wrapping, this is picking up from the row below. I found either method produced looser, longer stitches on the far edge

reaching the far right:

reaching the far right:

It does a good job of weighing down those straight edges along the bumps, making the stitches easier to pick up. When rehanging those stitches, uniformly hanging the loops, not the knots along the edges involved will give a smoother join. Here a paper clip is used as the “hanger”

It does a good job of weighing down those straight edges along the bumps, making the stitches easier to pick up. When rehanging those stitches, uniformly hanging the loops, not the knots along the edges involved will give a smoother join. Here a paper clip is used as the “hanger”

Lastly, a swatch ending in all knit rows. The only remaining issue is the fact that those side triangles are formed by stitches that are looser than across the rest of the piece. This yarn is thin and a poor choice, but fine for getting the technique down and beginning to understand what happens to stitches, how one needs to move from one side to the other, and what happens along the edges of each individual shape

Lastly, a swatch ending in all knit rows. The only remaining issue is the fact that those side triangles are formed by stitches that are looser than across the rest of the piece. This yarn is thin and a poor choice, but fine for getting the technique down and beginning to understand what happens to stitches, how one needs to move from one side to the other, and what happens along the edges of each individual shape

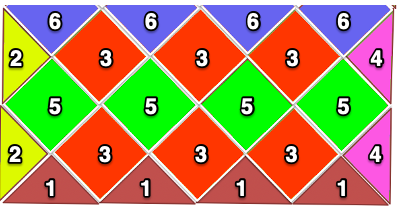

to consider the number of stitches required and whether the fact that other than garter stitch knit stitches are not square,

to consider the number of stitches required and whether the fact that other than garter stitch knit stitches are not square,

with a touch of steam and light pressing

with a touch of steam and light pressing

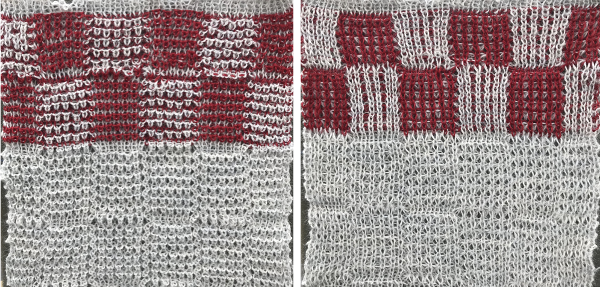

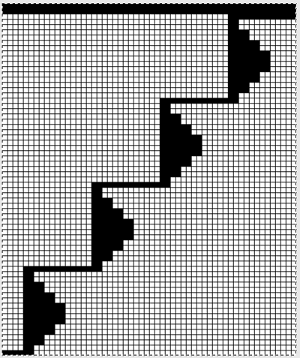

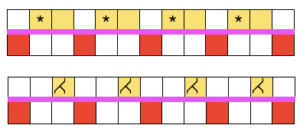

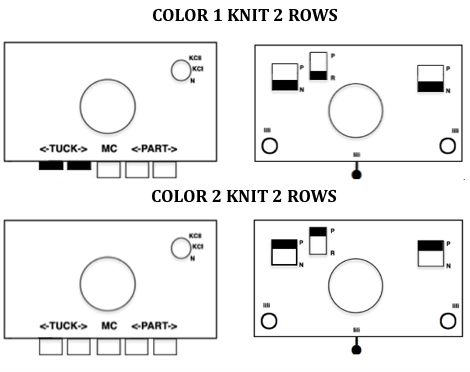

This is the isolated repeat for converting the pattern to a file suitable for download

This is the isolated repeat for converting the pattern to a file suitable for download  and its mirrored version for knitting from the opposite side

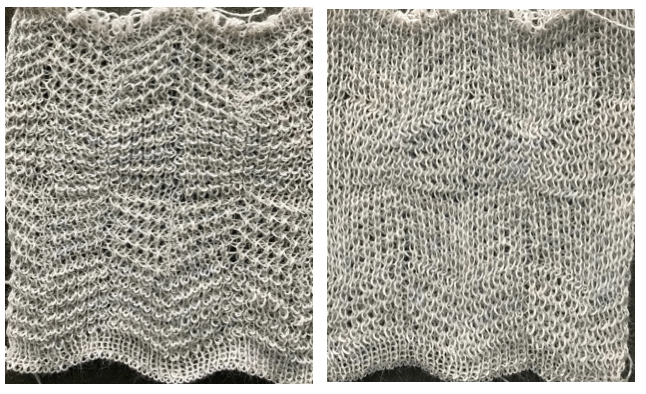

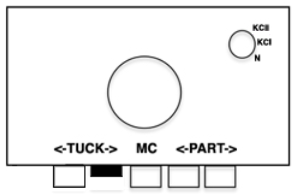

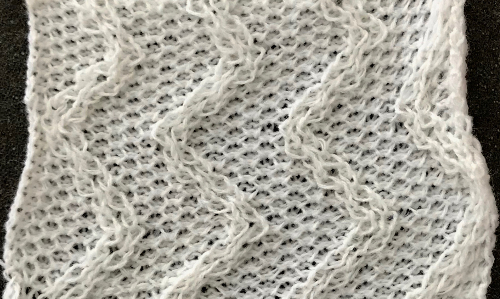

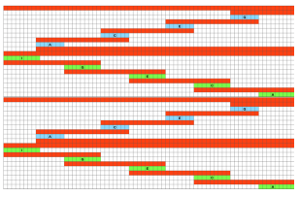

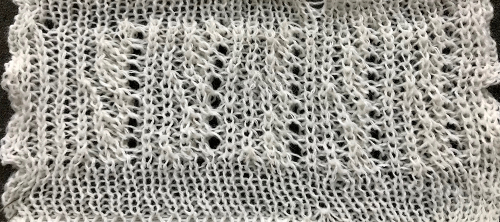

and its mirrored version for knitting from the opposite side  My test swatch was knit on the 930, using img2track. Because not every needle on the bed is in work throughout the knit, end needle selection must be canceled (KC II). The knit carriage after the preselection row is set to slip in both directions. Because only a few rows are knit on the red blocks in the chart, the result is subtle. The white yarn used in many of my tests happens to be a 2/24 acrylic, so on the too thin side, and likely to be well flattened if pressed.

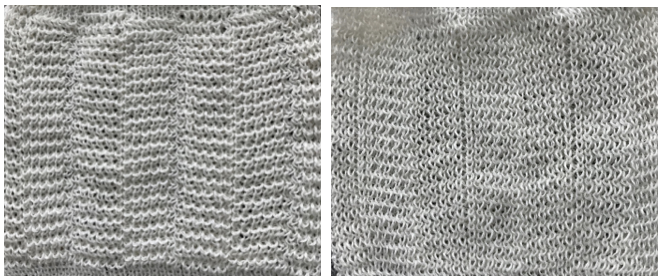

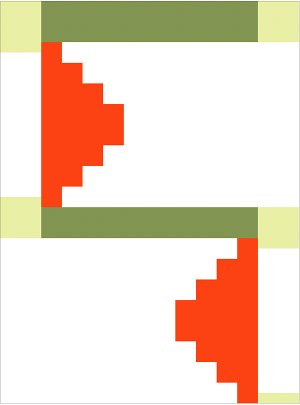

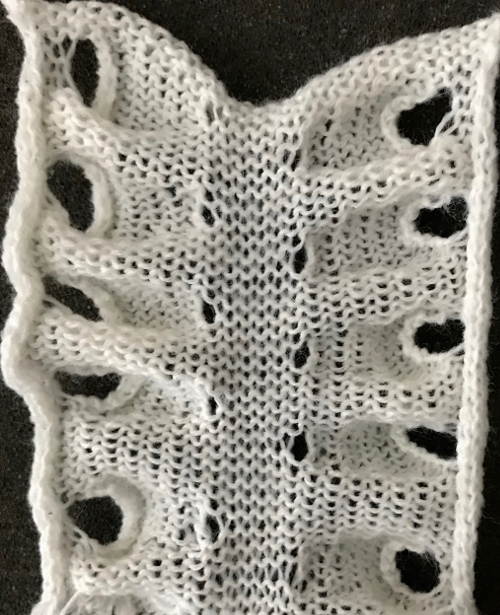

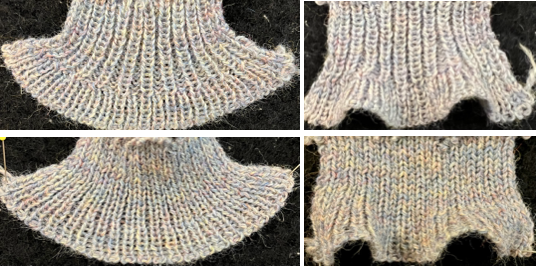

My test swatch was knit on the 930, using img2track. Because not every needle on the bed is in work throughout the knit, end needle selection must be canceled (KC II). The knit carriage after the preselection row is set to slip in both directions. Because only a few rows are knit on the red blocks in the chart, the result is subtle. The white yarn used in many of my tests happens to be a 2/24 acrylic, so on the too thin side, and likely to be well flattened if pressed. Often, the edge stitches on the carriage side will tend to be a bit tighter than those formed away from it. The same repeat may be used to create very different fabrics. Eliminating the all knit columns on either side of the center produces a piece with “ruffles” on either side of the center as the outer edge of each shape is no longer anchored down. The principle was used in knitting “potato chip” scarves popular in both hand and machine knitting for a while. Having a repeat on one side of an all knit vertical strip creates a ruffled edging.

Often, the edge stitches on the carriage side will tend to be a bit tighter than those formed away from it. The same repeat may be used to create very different fabrics. Eliminating the all knit columns on either side of the center produces a piece with “ruffles” on either side of the center as the outer edge of each shape is no longer anchored down. The principle was used in knitting “potato chip” scarves popular in both hand and machine knitting for a while. Having a repeat on one side of an all knit vertical strip creates a ruffled edging.

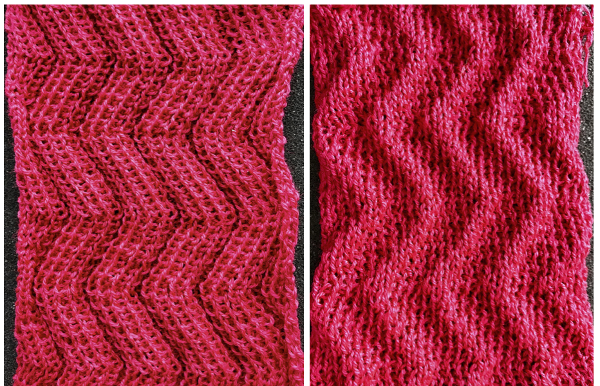

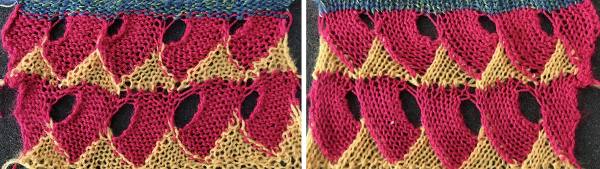

Note the effect of the added all knit rows on the “wave” of the piece on the right.

Note the effect of the added all knit rows on the “wave” of the piece on the right. The shapes for the “bumps” may be changed, moving away from rectangular formats. Small repeats are used for the purposes of illustration here, but they, in turn, may be scaled up, rendered asymmetrical, vary in placement, and more. My design steps began with this idea

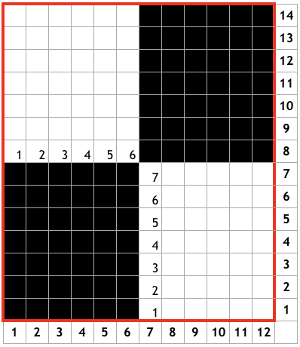

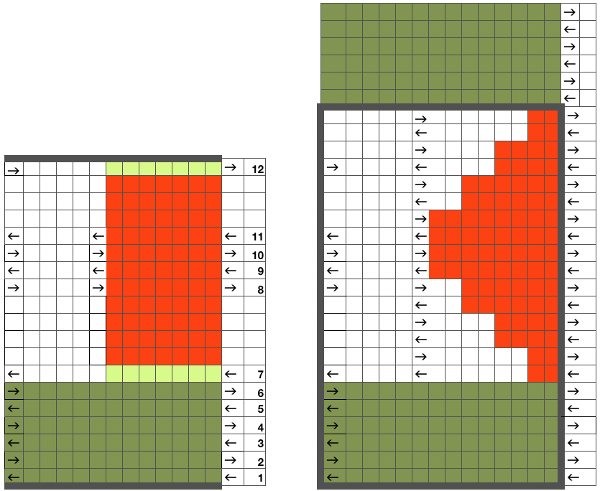

The shapes for the “bumps” may be changed, moving away from rectangular formats. Small repeats are used for the purposes of illustration here, but they, in turn, may be scaled up, rendered asymmetrical, vary in placement, and more. My design steps began with this idea Following the goal to achieve bilateral placement along a central vertical knit strip, with vertical knit strip borders at either side, here shapes point in the same direction

Following the goal to achieve bilateral placement along a central vertical knit strip, with vertical knit strip borders at either side, here shapes point in the same direction

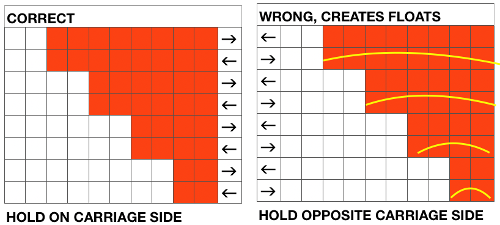

I ran into an interesting problem for the first time. I had entered the row and stitch counts on my chart, used those counts to scale the image used for my repeat down to size for knitting, kept getting floats where there should not have been any, could not understand what the error in the repeat might be. What was happening is that because of the wrong row number used in scaling, there was an extra pixel row in the first test swatches resulting in knitting errors. The final repeat is 29 stitches wide, 38 rows high. This is the resulting swatch

I ran into an interesting problem for the first time. I had entered the row and stitch counts on my chart, used those counts to scale the image used for my repeat down to size for knitting, kept getting floats where there should not have been any, could not understand what the error in the repeat might be. What was happening is that because of the wrong row number used in scaling, there was an extra pixel row in the first test swatches resulting in knitting errors. The final repeat is 29 stitches wide, 38 rows high. This is the resulting swatch

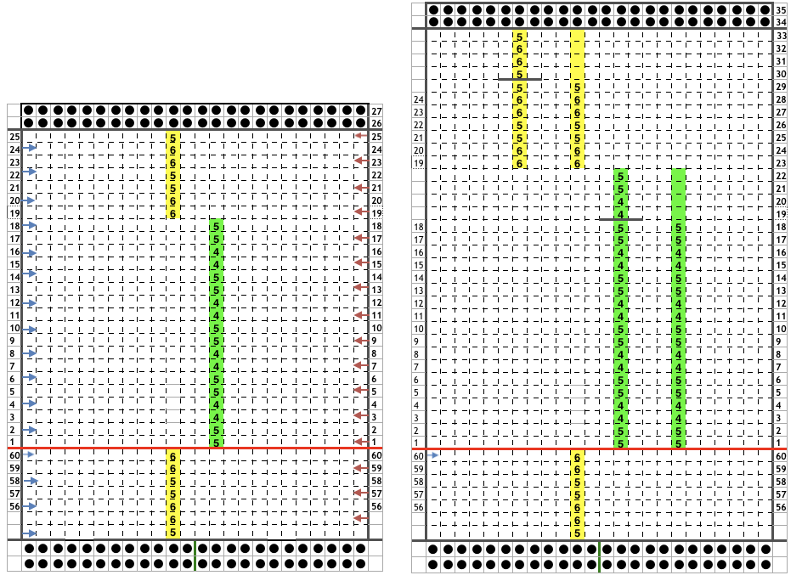

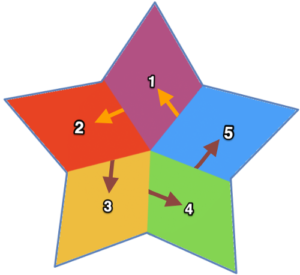

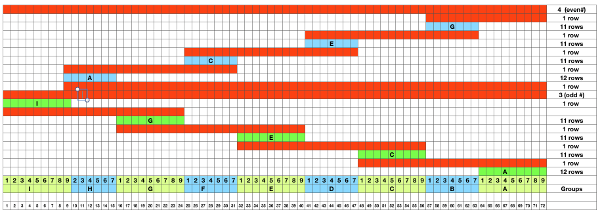

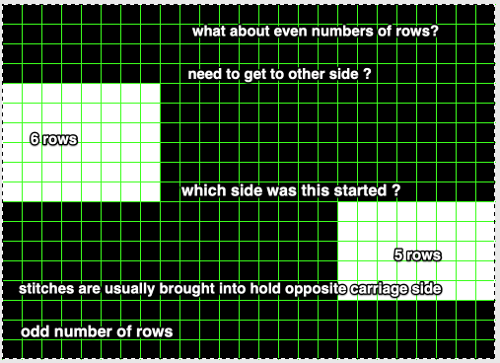

Once more, the repeat could be reduced down to eliminate side knit strips, or limit shapes to one side only for a one-sided ruffle. What about repeating the same slit horizontally across a row? Repeats become very long, arrows are intended again as guides in the knitting direction.

Once more, the repeat could be reduced down to eliminate side knit strips, or limit shapes to one side only for a one-sided ruffle. What about repeating the same slit horizontally across a row? Repeats become very long, arrows are intended again as guides in the knitting direction.  An even number of rows (green) at the end of the outlined repeat will return the carriage to begin knitting it from the right side once more. An odd number of rows added at its top will prepare for knitting the motifs beginning on the left.

An even number of rows (green) at the end of the outlined repeat will return the carriage to begin knitting it from the right side once more. An odd number of rows added at its top will prepare for knitting the motifs beginning on the left.

Pushing unwanted needle groups back to the D position will make them knit rather than being held, which is another way to vary the texture distribution across any single row

Pushing unwanted needle groups back to the D position will make them knit rather than being held, which is another way to vary the texture distribution across any single row

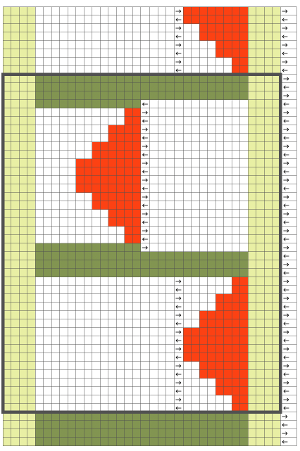

The reverse side shows the same issue. Areas can be identified where the held stitches have been hung up to create hems. Note that as the knit grows in length, at the completion of each row of repeats there is one segment with no hem on alternating sides. A longer test swatch follows

The reverse side shows the same issue. Areas can be identified where the held stitches have been hung up to create hems. Note that as the knit grows in length, at the completion of each row of repeats there is one segment with no hem on alternating sides. A longer test swatch follows

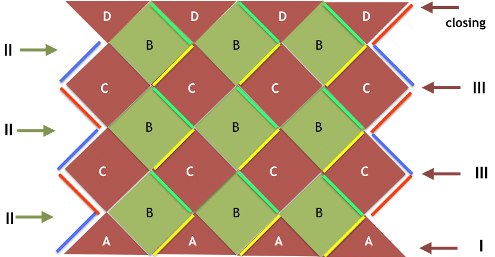

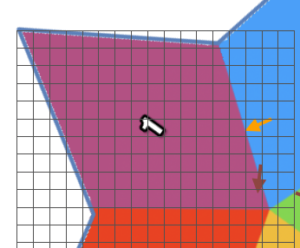

I created my hems on the carriage side, immediately prior to bringing the following group of stitches into work opposite it, and knitting a single row across that new group of 3 segments. The highlighted area indicates the stitches to be hung to create the hem. The eyelet on the top, right, will be smaller than the one at the opposite side of the stitches to be hung up

I created my hems on the carriage side, immediately prior to bringing the following group of stitches into work opposite it, and knitting a single row across that new group of 3 segments. The highlighted area indicates the stitches to be hung to create the hem. The eyelet on the top, right, will be smaller than the one at the opposite side of the stitches to be hung up

Reversing the direction of segments

Reversing the direction of segments

This is one of my early graphics trying to imagine what is happening in chart form, which also references the repeat in the Passap garment, followed by plain knitting

This is one of my early graphics trying to imagine what is happening in chart form, which also references the repeat in the Passap garment, followed by plain knitting

This fabric is worked out differently, in groups of 2. After the first segment is completed, COR if the starting group 1 worked is on the right, bring group 2 into work, knit one row to left, immediately bring group one into hold, and continue across row. That “float” is created as the yarn traveling between the last stitch on the right now coming into hold and the first stitch to its left knits for many more rows gets pulled on as the piece grows.

This fabric is worked out differently, in groups of 2. After the first segment is completed, COR if the starting group 1 worked is on the right, bring group 2 into work, knit one row to left, immediately bring group one into hold, and continue across row. That “float” is created as the yarn traveling between the last stitch on the right now coming into hold and the first stitch to its left knits for many more rows gets pulled on as the piece grows.

Hems in knitting can be created on any number of stitches, anywhere on a garment, by definition join segments of the knit together permanently. Folds are freer. Here is an attempt at a different wisteria cousin with organized repeats. More on creating it will follow in a subsequent post now that holding techniques are back on my radar

Hems in knitting can be created on any number of stitches, anywhere on a garment, by definition join segments of the knit together permanently. Folds are freer. Here is an attempt at a different wisteria cousin with organized repeats. More on creating it will follow in a subsequent post now that holding techniques are back on my radar

I like to chart out my repeats and plans for executing fabrics, along with ideas for possibly varying them in ways other than suggested, this was my beginning

I like to chart out my repeats and plans for executing fabrics, along with ideas for possibly varying them in ways other than suggested, this was my beginning

knit one more row to return to the opposite side

knit one more row to return to the opposite side

I knit 3 rows rather than 2, to return to right side for bind off

I knit 3 rows rather than 2, to return to right side for bind off  here is the swatch, still on comb for “setting stitches”

here is the swatch, still on comb for “setting stitches”

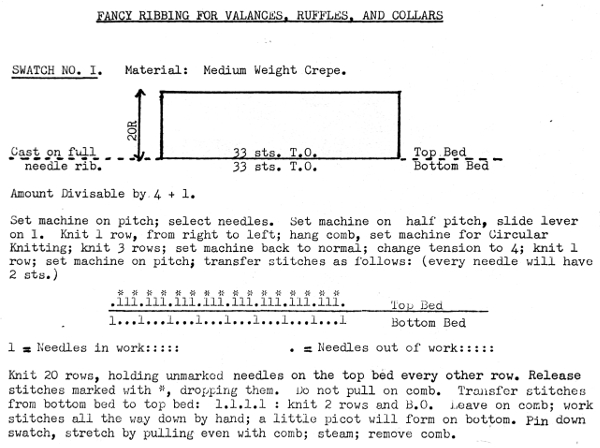

when the 20 rows are completed the carriages will once again be on the right, all stitches will have been knit on the previous row

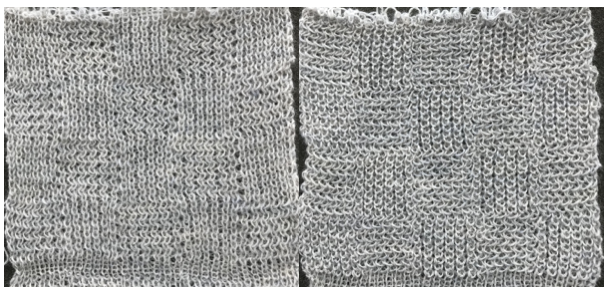

when the 20 rows are completed the carriages will once again be on the right, all stitches will have been knit on the previous row  transfer all ribber stitches to top bed, knit 2 rows, bind off. None of my swatches were blocked other than by some tugging, particularly along the bottom edge. The spacing between stitches is narrower because ladders created by single needles left out of work are formed by yarn lengths that are shorter than those that happen when stitches are knit and then in turn dropped. The height of the swatch is also affected, and the half fisherman texture in the wool swatch, in particular, is more evident.

transfer all ribber stitches to top bed, knit 2 rows, bind off. None of my swatches were blocked other than by some tugging, particularly along the bottom edge. The spacing between stitches is narrower because ladders created by single needles left out of work are formed by yarn lengths that are shorter than those that happen when stitches are knit and then in turn dropped. The height of the swatch is also affected, and the half fisherman texture in the wool swatch, in particular, is more evident. When the work is removed from the machine, stretch cast on outwards, then give each “scallop” a really good pull downwards. Steam lightly over the scallops to set them. Variations of the double bed trims may be worked on the single bed as well.

When the work is removed from the machine, stretch cast on outwards, then give each “scallop” a really good pull downwards. Steam lightly over the scallops to set them. Variations of the double bed trims may be worked on the single bed as well.

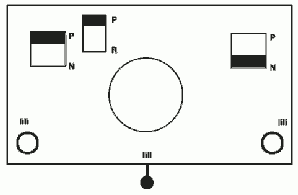

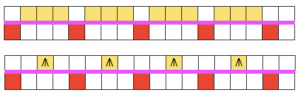

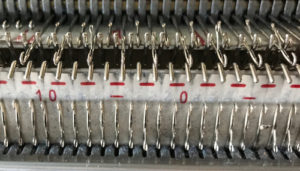

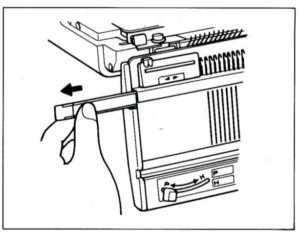

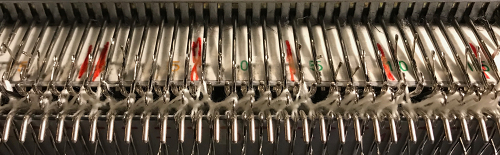

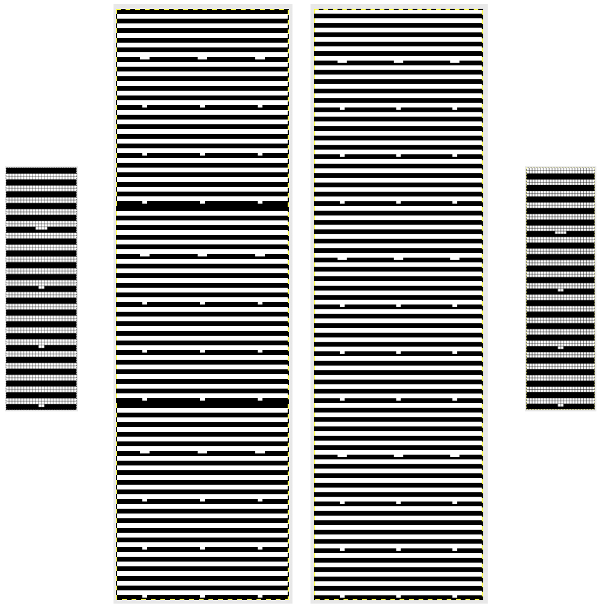

Working it on Brother becomes a bit fiddly. Whether working on a punchcard or electronic KM, it is possible to introduce patterning on either or both beds as seen below. I preferred the look obtained with the racked cast on at the start. Setting up the Brother machine: program the repeat, half pitch for every needle rib, air knit to place the pattern on the bed so that the first needle on the left (or right if you prefer) is preselected forward and will produce a knit stitch on the first row knit. The yarn used is a 2/24 acrylic

Working it on Brother becomes a bit fiddly. Whether working on a punchcard or electronic KM, it is possible to introduce patterning on either or both beds as seen below. I preferred the look obtained with the racked cast on at the start. Setting up the Brother machine: program the repeat, half pitch for every needle rib, air knit to place the pattern on the bed so that the first needle on the left (or right if you prefer) is preselected forward and will produce a knit stitch on the first row knit. The yarn used is a 2/24 acrylic

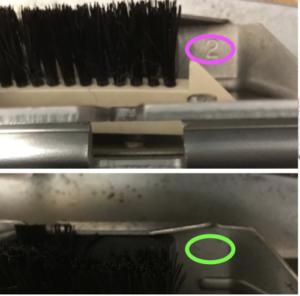

now another needle on the ribber is brought in to work on the far left, it will tuck with lili selection when moving from left to right

now another needle on the ribber is brought in to work on the far left, it will tuck with lili selection when moving from left to right  remember the ribber rule with lili buttons: an even number of needles must be in work, this shows the start and end of selection on the ribber on alternate needle tape markings, as required

remember the ribber rule with lili buttons: an even number of needles must be in work, this shows the start and end of selection on the ribber on alternate needle tape markings, as required

Both pieces compared for width and rippling

Both pieces compared for width and rippling

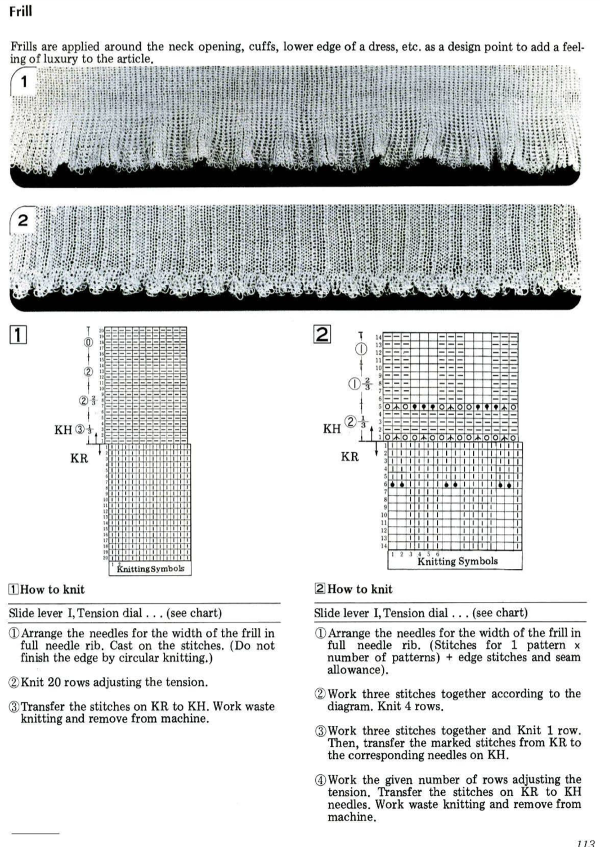

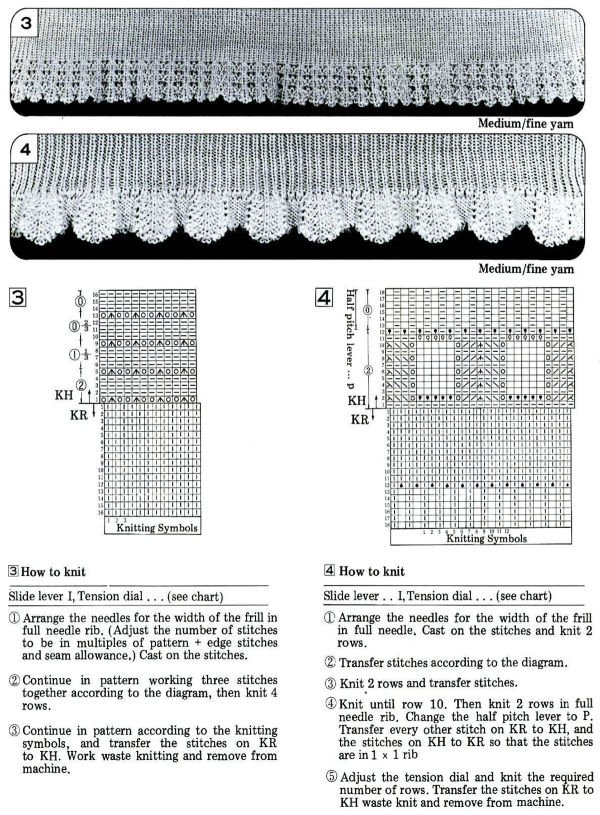

An intro to scallops: p.120

An intro to scallops: p.120

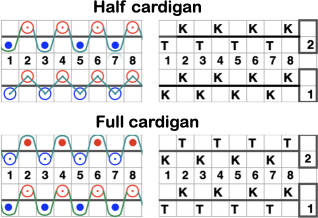

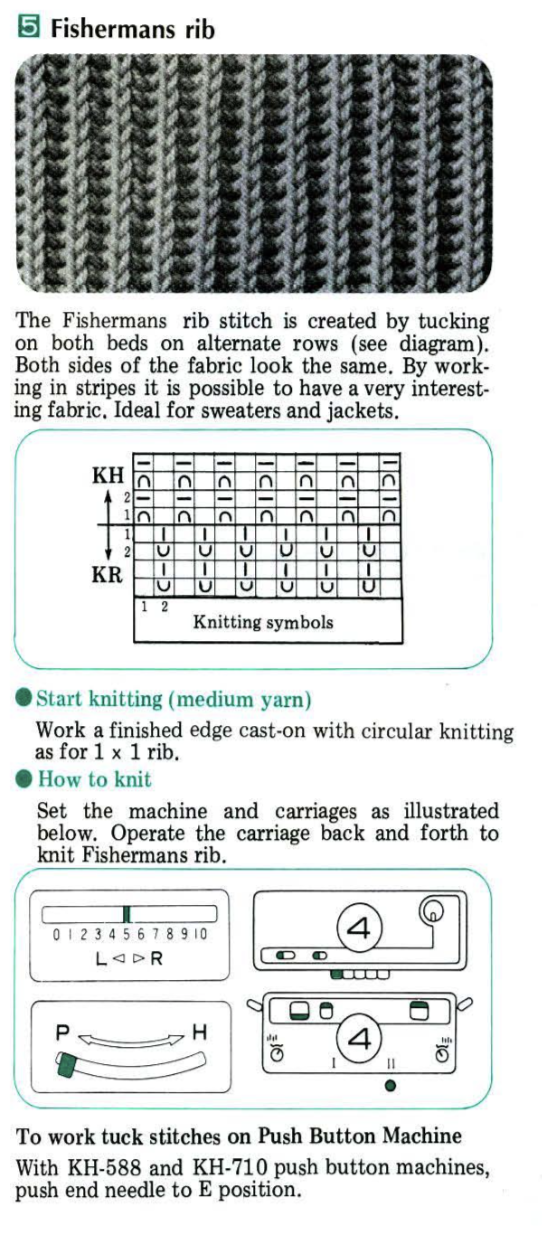

Fisherman, aka full fisherman rib, is a tubular tuck with each bed tucking in one direction, knitting in the other

Fisherman, aka full fisherman rib, is a tubular tuck with each bed tucking in one direction, knitting in the other

Can plaiting give me 2 colors the “easy” way?

Can plaiting give me 2 colors the “easy” way?

its reverse side :

its reverse side :

This is what happens when a new design is being tested, and the lili buttons “accidentally” happen to be engaged on the ribber

This is what happens when a new design is being tested, and the lili buttons “accidentally” happen to be engaged on the ribber

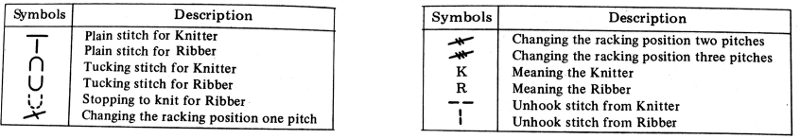

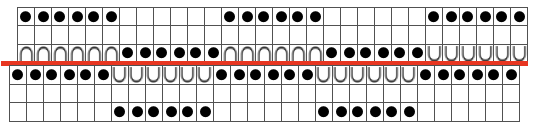

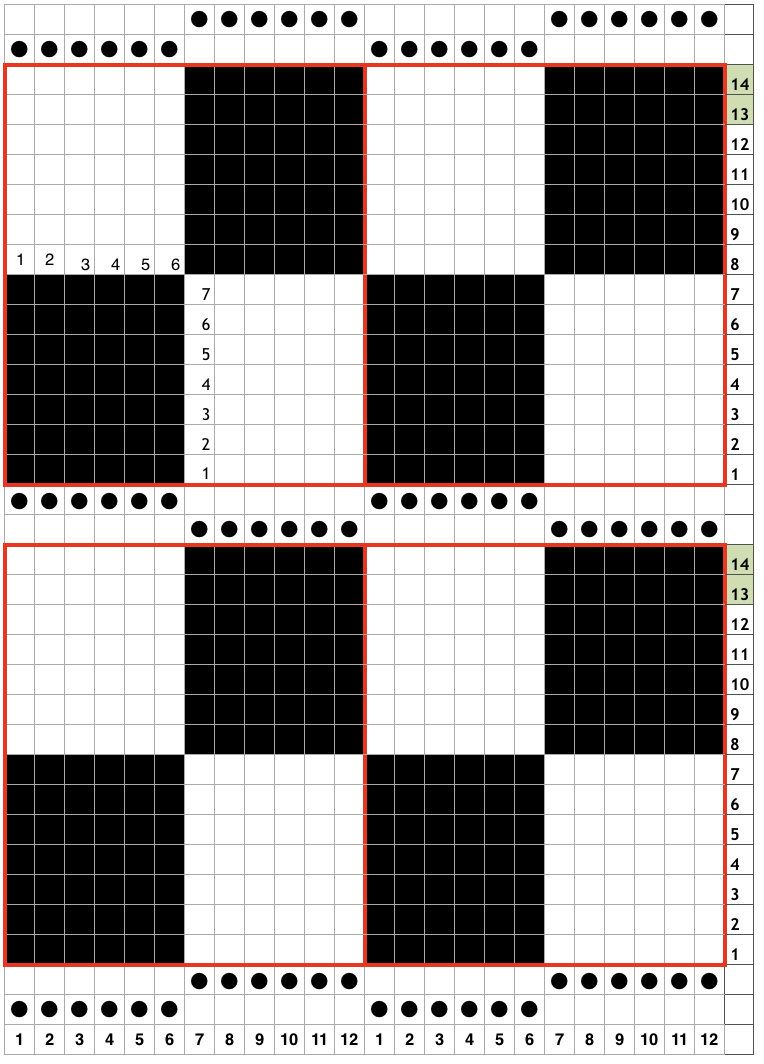

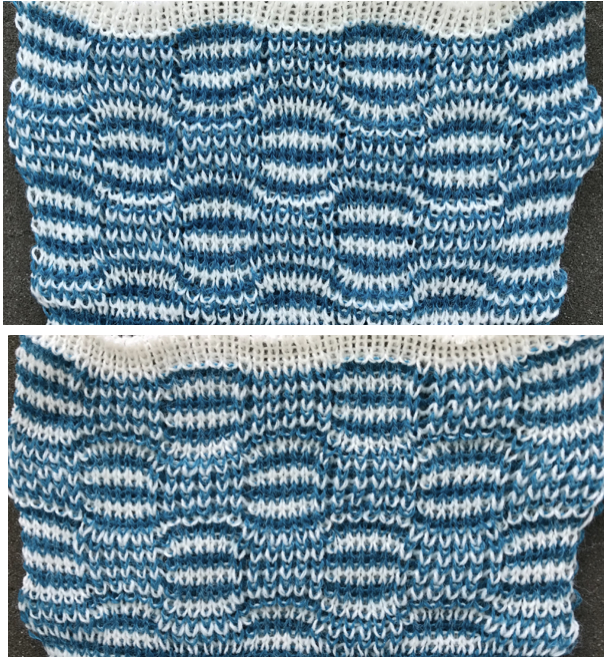

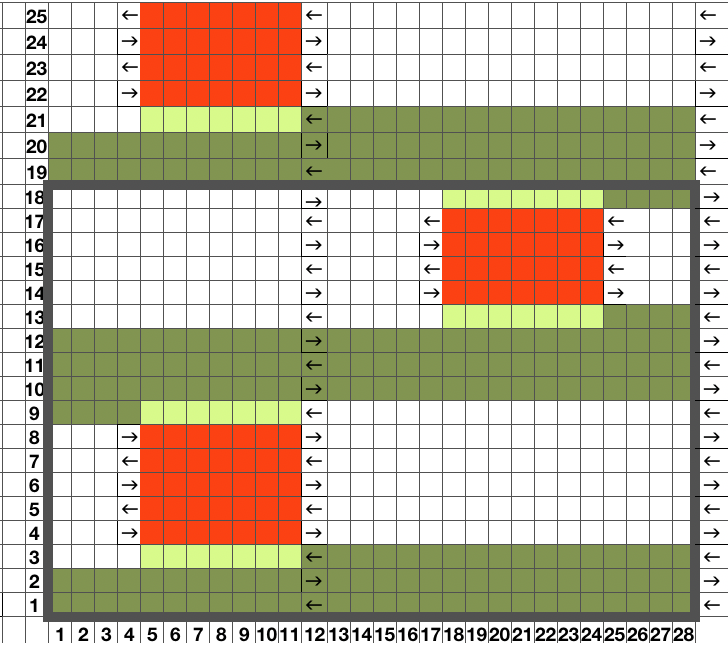

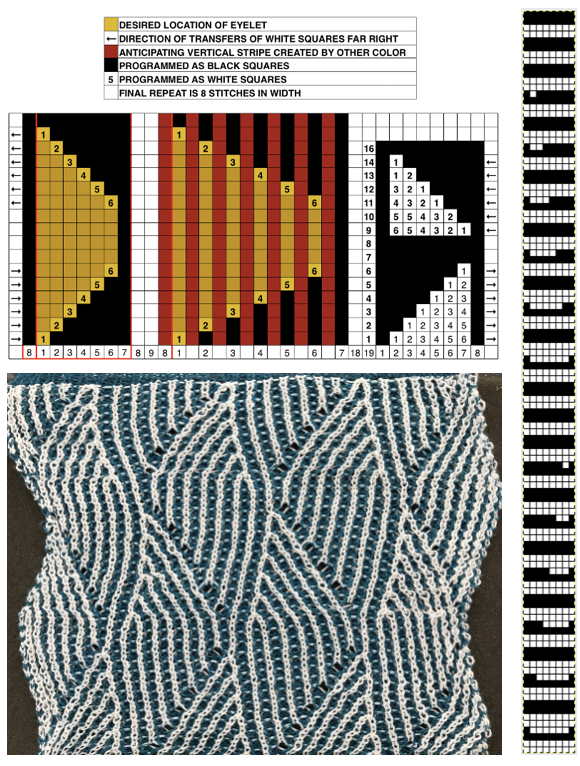

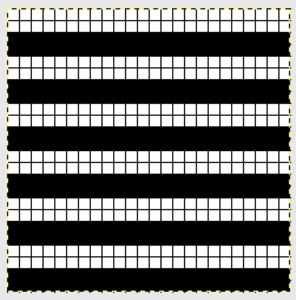

Each of the 2 colors tucks for 2 rows and in turn, knits for 2 rows alternately. Settings are changed manually as shown below after every 2 rows knit, following each color change on the left.

Each of the 2 colors tucks for 2 rows and in turn, knits for 2 rows alternately. Settings are changed manually as shown below after every 2 rows knit, following each color change on the left.  Making things a little easier: the top bed may be programmed on any machine, including punchcard models to avoid cam button changes in the knit carriage every 2 rows. With the main bed set to tuck <– —> throughout, black squares will knit for 2 rows, white squares will tuck, also for 2 rows. The first preselection row is toward the color changer. When no needles are selected on the top bed (white squares) the top bed will tuck every needle, the ribber is set to knit.

Making things a little easier: the top bed may be programmed on any machine, including punchcard models to avoid cam button changes in the knit carriage every 2 rows. With the main bed set to tuck <– —> throughout, black squares will knit for 2 rows, white squares will tuck, also for 2 rows. The first preselection row is toward the color changer. When no needles are selected on the top bed (white squares) the top bed will tuck every needle, the ribber is set to knit.

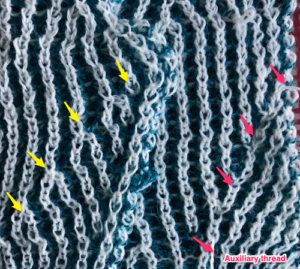

Another attempt at cabling, 1X1 and 2X2. That white line in the bottom image on the right was caused by the color changer picking up and knitting both colors for part of the row before I noticed it. I got rid of the “wrong” color from the feeder and continued on. The wider 2X2 cables require “special handling” and eyelets are formed on columns aside from them after transfers are made.

Another attempt at cabling, 1X1 and 2X2. That white line in the bottom image on the right was caused by the color changer picking up and knitting both colors for part of the row before I noticed it. I got rid of the “wrong” color from the feeder and continued on. The wider 2X2 cables require “special handling” and eyelets are formed on columns aside from them after transfers are made.

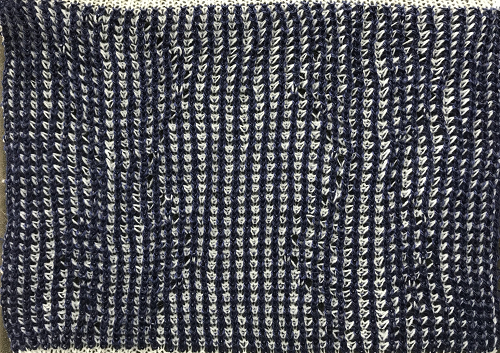

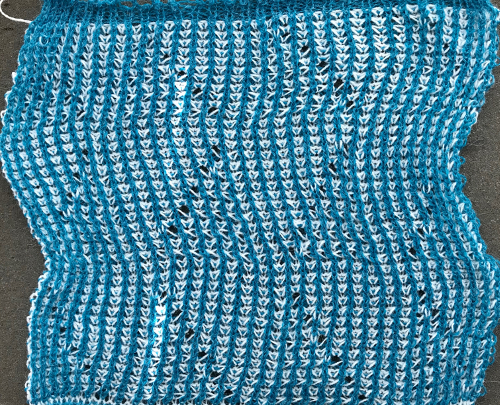

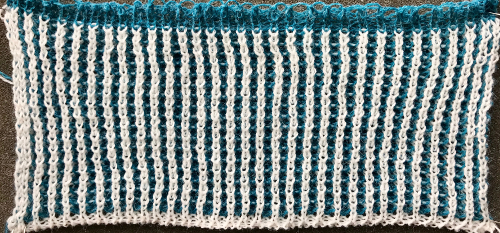

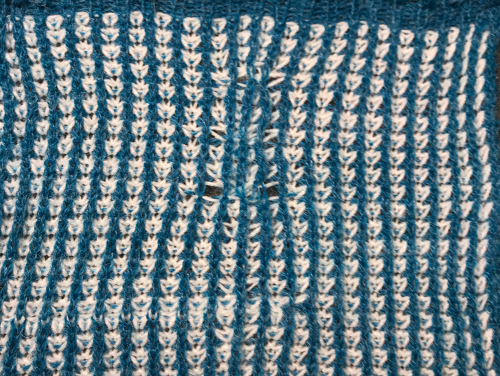

The situation is different when working on single bed vertically striped fair isle designs. One of my ancient machine-knit demo FI swatches:

The situation is different when working on single bed vertically striped fair isle designs. One of my ancient machine-knit demo FI swatches:

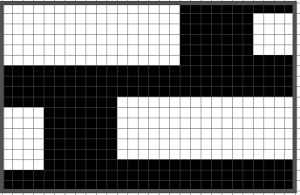

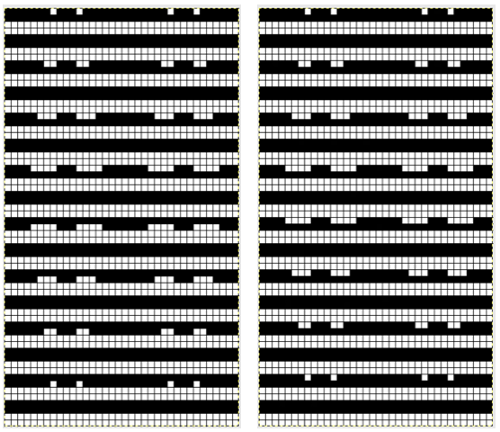

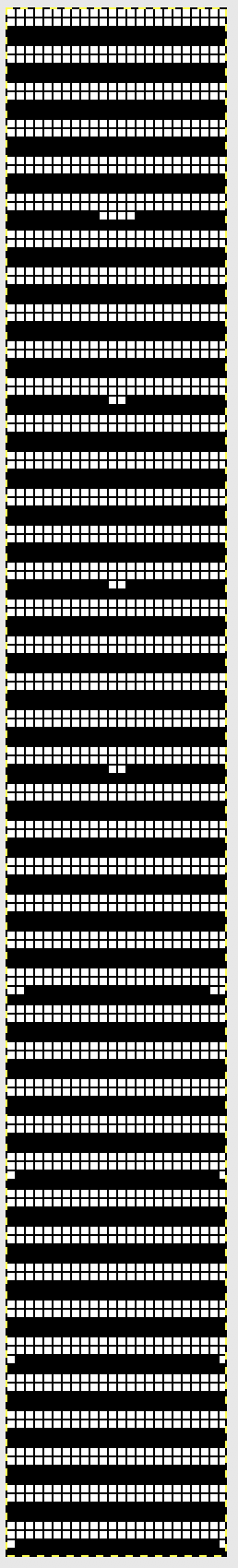

The charted repeat on the left below when tiled shows the area of a patterning error, on the right with the missing blank rows added the problem is shown to be resolved, the repeat is now 24 X 84.

The charted repeat on the left below when tiled shows the area of a patterning error, on the right with the missing blank rows added the problem is shown to be resolved, the repeat is now 24 X 84.

Adding complexity, there is the possibility of

Adding complexity, there is the possibility of